Today in Irish History –The Fenian Rebellion, March 5, 1867

John Dorney on the abortive republican insurrection of 1867.

John Dorney on the abortive republican insurrection of 1867.

Very early on the morning of March 5th 1867, many thousands of young men, some of them well armed, others not, set off from Dublin towards the hills overlooking the village of Tallaght.

The police noted that a large number of (horse-drawn) cars left the Combe and Kevin Street area for the countryside. Others walked to Tallaght.

The police sergeant at Crumlin reported that, “the Dublin road is crowded with young men, all taking the direction of Tallaght”.

The young men, who may have numbered up to 8,000, were Fenians – members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and this was the day of a long-planned-for insurrection aimed at toppling British rule and establishing an Irish Republic.

Most of them were there by choice, having been ordered by the “centre” or commander or their IRB “circle”, or unit of 800 men, but those who were reluctant to go were given encouragement; “If you don’t go, by God you’ll be shot”, one was told.[1]

As many as 10,000 armed Fenians came out in rebellion. Up to 7,000 assembled at Tallaght.

William Domville Handcock, a Tallaght landowner and Magistrate for County Dublin, recalled later, “At my uncle’s place at Kiltalown, the family were in a great fright. They saw numbers of Fenians walking about the lawn all night, and they expected to be attacked every moment”.[2]

Slightly further east in the Dublin hills, another band of some 200 Fenians attacked and took a string of Irish Constabulary barracks, at Dundrum, Stepaside and Glencullen.

In Drogheda, as many as 1,000 Fenians assembled in the Market Square, armed with pikes and rifles and refused an order from 28 policemen to disperse.

In Cork, about 4,000 insurgents gathered at Fair Hill and proceeded to Limerick train Junction, in the process attacking and burning several police barracks. [3]

The Fenians, led by James Stephens, a charismatic republican revolutionary, exiled in Paris, where he associated with like-minded radicals, issued a Proclamation of the Irish Republic;

Our rights and liberties have been trampled on by an alien aristocracy, who, treating us as foes, usurped our lands and drew away from our unfortunate country all material riches

We appeal to force as a last resort… unable to endure any longer the curse of a monarchical government, we aim at founding a Republic based on universal suffrage, which shall secure to all the intrinsic value of their labour.

The soil of Ireland, at present in possession of an oligarchy, belongs to us, the Irish people and to us it must be restored. We declare also in favour of absolute liberty of conscience and the separation of Church and State. We intend no war against the people of England; our war is against the aristocratic locusts, whether English or Irish, who have eaten the verdure of our fields.[4]

But by the following day, the Rising, what the unionist Irish Times described as, “this wretched conspiracy”, was over. The Fenians, over 10,000 strong, had been dispersed and were being hunted through the hills by the Irish Constabulary and the British Army.

‘The Curse of monarchical government’

The Irish Republican Brotherhood or Fenian Brotherhood was founded in Dublin by James Stephens in 1858. In many ways it was the first popular political movement in Ireland to both led and supported by, “the common man”.

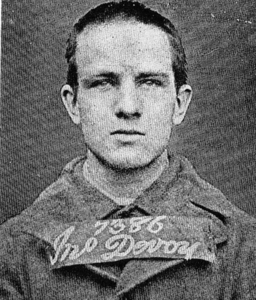

Stephens himself was a civil engineer, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa came from an evicted farming family who set themselves up as grocers, while John Devoy was a labourer’s son from Kildare. Their organisation, which by 1867, was 50,000 strong, drew its support from the lower classes of both town and country.

The Fenians, most importantly, were also the first Irish movement to draw on the sympathy, wealth and military expertise of the Irish–American community. The military leaders of the 1867 Rising were Irish veterans of the Union Army in the American Civil War.[5]

Why the message of Irish republican revolution, anti-British and anti-landlord, found so many willing adherents in 1860s Ireland is no great mystery. Even after the 1850 Reform Act, which broadened the electorate to every man with property of over 12 pounds, only one sixth of adult Irishmen as opposed to one third of Englishmen (women of course were excluded altogether until 1918) had the vote.

Voting also had to be made in public until 1872, meaning that a tenant who voted against his landlord could expect to feel the consequences. So it was not necessarily affection that elected landlords as some 50-70% of Irish MPs up to 1883.[6] When the Fenians talked about rule by, “an oligarchy”, they knew what they were talking about.

One sixth of Irishmen, compared to one third of Englishmen, had the vote in 1867. 50-70% of Irish MPs were landlords

The Great Famine, where tens of thousands of families had been evicted from their homes by landlords and where the British government had been widely pilloried for its failure to avert the death of a million people, was not yet 20 years in the past.

What Fenianism represented was not so much a complicated set of political ideas as a defiant attitude towards the social order and the British regime in Ireland. Drawing on earlier traditions of secret societies like the Whiteboys, Rockite and Ribbonmen, Fenian “circles” would meet on hill tops and drill openly with arms, asserting their equality with their supposed betters and challenging the Police and Army to do something about it.

‘We appeal to force as a last resort’

In 1865, the British government suppressed the Fenian paper, The Irish People and arrested Stephens, and several hundred other activists (Stephens later escaped however). In 1866, habeus corpus, or normal, peacetime law, was suspended in Ireland.

In 1865, the British government suppressed the Fenian paper, The Irish People and arrested Stephens, and several hundred other activists (Stephens later escaped however). In 1866, habeus corpus, or normal, peacetime law, was suspended in Ireland.

The remaining Fenian leadership, rather than see the movement go down without a fight, set about organising an insurrection for early 1867. Thomas Kelly, an Irish American Civil War veteran, was made “Deputy Central Organiser of the Irish Republic” – with responsibility for planning the rebellion. The actual military planning was done by one General Millen, another Civil War veteran.

The plan, which would centre around action in Dublin went through three drafts. The first, proposed by James Stephens, suggested the storming and seizure of the three main military arsenals in Dublin at Pigeon House Fort, Magazine fort and Portobello barracks. Millen rejected it due to the Fenians’ lack of arms.

The second proposal, made by John Devoy (who was however arrested in February 1866), was based on infiltration of the Army. Fenian soldiers would mutiny and take over the military barracks in the city, as a signal for insurrection.

The Fenians’ plan centred on Dublin. The mobilisation at Tallaght was supposed to be a diversion from an uprising in the city.

Again, Millen rejected the plan, but it was certainly made in earnest. On January 7, 1867, the Irish Times reported on the trial of three soldiers at Royal (now Collins’ Barracks) in Dublin, charged with, “enlisting to corrupt the Irish soldiers by speaking patriotically to them”. Those who would not take the Fenian oath were to be shot when the Rising took place, “and the arms of the loyal troops rendered useless”.[7]

What Millen settled on in the end was two-stage plan. In the first stage, the Fenians would wage guerrilla warfare, to cut rail and road communication and, “in bands of 15-20 men…to never fight regularly against the troops or police…[but to] resort to ambuscades to cut off isolated or small parties of police or soldiers”.[8]

The mobilisation at Tallaght on March 5 was a decoy, intended to draw the British forces out of Dublin for stage two; insurrection in the city.

From the start things went wrong. A Fenian “centre” in Liverpool, John Joseph Croydon, told the Irish Constabulary exactly what was going to happen. Extra troops were drafted into Dublin and four gun boats were seen on the Liffey.

In the face of overwhelming force, well informed of their plans, the Fenian’s rebellion fell apart into isolated skirmishes.

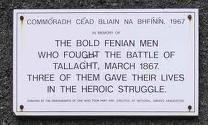

The ‘Battle of Tallaght’

The Irish Constabulary Sub-Inspector at Tallaght, Burke of Rathfarnham, Dublin, known in the area as “Chief Burke”, was watching the armed exodus from Dublin city to Tallaght Hill. In response he took 14 well armed- constables out onto the crossroads between Tallaght and the two roads from the city, via Greenhills and via Terenure (then known as Roundtown) to intercept the various bands making their way south.

The Irish Constabulary Sub-Inspector at Tallaght, Burke of Rathfarnham, Dublin, known in the area as “Chief Burke”, was watching the armed exodus from Dublin city to Tallaght Hill. In response he took 14 well armed- constables out onto the crossroads between Tallaght and the two roads from the city, via Greenhills and via Terenure (then known as Roundtown) to intercept the various bands making their way south.

The first group he encountered was 40 strong and was pushing a cart. One of the police putting his hand into the cart, found it full of ammunition, a scuffle ensued. One Fenian, Thomas Farrell, a confectioner, of Williamstown, was bayoneted in the stomach. His body was later found by the roadside in Terenure.[9]

Shortly afterwards, another group of Fenians, some 150 men under Stephen O’Donoghue, a 35-year-old law clerk of Werburgh street in Dublin city, encountered the police on the roadside. Burke called on them to surrender, but, despite orders not engage large bodies of police, “a number of very young fellows” opened fire, though not, Burke told the inquest, “in any direction”.

The police knelt and returned fire in volleys, leaving six Fenians bloodied on the ground. The remaining Fenians, according to Burke, “ran away in the greatest disorder”.

“Although I did my duty, I will regret to my last day that the life of one of my countrymen should have been sacrificed.”: Irish Constabulary Sub Inspector Burke, March 8, 1867

One was killed outright. Another was Stephen O’Donoghue, the centre, who was “groaning and asking for water”. The police took him to the barracks at Tallaght, where he died. O’Donoghue, who was described as, “a very poor man”, had been married with four children.

Burke told the inquest, that although, “I did my duty, I will regret to my last day that the life of one of my countrymen should have been sacrificed.”[10]

William Handcock, who lived nearby recalled, “We heard the firing that night, but did not know the cause. Next morning most wonderful stories came in. Numbers of the Fenians had passed through the village outside our wall, and tried to induce the villagers to join them, but with little success.”[11]

This was the ‘Battle of Tallaght’. It was in fact, a mere brush between the police and the Fenians trying to get to Tallaght Hill.

The real failure of the Rising was that, with 4-7,000 men assembled on the Hill, above Jobstown, the Fenian leadership could think of little for them to do. The mobilisation there was supposed to have been a diversion from the real rebellion in Dublin city. But the city, heavily garrisoned, did not stir.

After a night of enduring heavy snow and sleet in the Dublin mountains, the Fenians, dispersed. Some 200 were arrested.

Elsewhere in the country, when it became clear that the plan had not come off, most of the Fenians simply went home and hid their weapons. The Rising, which had never properly started, was over.

A total of 12 people were killed on March 5, of whom eight were Fenians.

‘A teacup rebellion’

The Irish Times gloated that the rebels, “who have inflicted the greatest amount of trouble on the government, loyal people and filled with alarm the isolated houses of the gentry…have shown themselves excellent at everything except actual rebellion”.[12]

It praised the actions of British commander Lord Strathrairn, who, before suppressing sedition in Ireland, “had ridden down the mutinous Sepoys in India”, for his “rapidity of actions and decision”.

It scoffed at the rebels’ claim to be acting in the name of the ‘Minister for war of the Irish Republic, “this craze is dangerous to society, it is the bounden duty of government to deal with it severely.’[13]

William Handcock found in the plantations near his house in Tallaght, “nearly a cart-load of rifles and ammunition … Next day we got a fine pike-head and a neat little dagger, as souvenirs of the latest, and, as I hope, the last, rebellion in Ireland”.[14]

The more nationalist-minded Freeman’s Journal had little sympathy for the attempted insurrection but noted the urgent need for reform of the state and church and of the tenant system. “The Fenians, with their teacup insurrections are not likely to remedy the state of things, [but] the British government which allows grievances to fester for centuries, can expect little sympathy from abroad or peace and contentment at home”.[15]

The 1867 Rising never got off the ground and in the following decades the British did make many reforms, including of the land system. But the Fenians had founded a powerful tradition/

In fact, in the late 19th and early 20th century, the British government did indeed undertake extensive reforms of the electoral system and of the land question. But the Fenians had nevertheless founded a powerful tradition.

Many years later, in 1920, during the War of Independence, Ernie O’Malley, a young IRA commander, full of soldierly swagger, found himself put up in a farm house in the hill country of west Cork by an old Fenian.

“ ‘Out there in yon hills, I’ve drilled with the boys in me time, fine boys they were, God Bless them’. ‘But the Fenians did not do much’, I said, ‘Why didn’t they fight?’ He looked me for a moment as if he was going to say something strong. ‘They were ready and willing and always waiting for the word to rise. He looked at our automatics and rifles. They’d be powerful yokes, I wish we’d had them in our time’ ”.

‘Do you think we’ll beat them? How long will it last?’ ‘We don’t know’, said Liam [Lynch], a long time, but we’ll win’”[16]

[1] Shi Ichi, Takagami, The Fenian Rising in Dublin, March 1867, Irish Historical Studies XXIX, no 115 (May 1995)

[2] William D Handcock, The Battle of Tallaght, in The History and Antiquities of Tallaght In The County of Dublin, 1899. The police in Ireland gained their title ‘Royal’ Irish Constabulary for their role in putting down the 1867 rebellion. At this date they were just the ‘Irish Constabulary’.

[3] The Irish Times, March 7 1867

[4] Joseph Lee, The Modernisation of Irish Society 1848-1918, p56

[5] Lee, p57

[6] James H. Murphy, Ireland, A Social, Cultural and Literary History, 1791-1891, p116

[7] Irish Times January 7, 1867

[8] For all on the planning, Takagami, Fenian Rising in Dublin.

[9] Irish Times, March 8, 1867. Handcock, History and Antiquities of Tallaght.

[10] Irish Times, March 8 1867.

[11] Handcock, History and Antiquities of Tallaght.

[12] Irish Times, March 8, 1867

[13] Irish Times, March 7, 1867

[14] Handcock, History and Antiquities of Tallaght

[15] Freeman’s Journal, March 14, 1867

[16] Ernie O’Malley, On Another Man’s Wound, p223-224