Today in Irish History, The Repeal Meeting at Clontarf is Banned, 8 October 1843

John Dorney remembers the day that Daniel O’Connell’s agitation for Repeal of the Union between Britain and Ireland was halted in its tracks.

On the night of Saturday, October 7, 1843, a proclamation was issued from Dublin Castle banning the meeting called by Daniel O’Connell north of the city at Clontarf on the following day.

It was written by the Prime Minister of Britain and Ireland, Sir Robert Peel, who called the proposed meeting for the restoration of the Irish Parliament, abolished in 1801, “an attempt to overthrow the constitution of the British Empire as by law established”.[1]

Two warships, the Rhathemus and the Dee, steamed into Dublin Harbour, carrying around 3,000 British troops from the 24th and 34th regiments to ensure the mass rally in favour of Repeal of the Union did not take place.

The nationalist newspaper, the Freeman’s Journal alleged that the troops had been summoned to, “cut the people down” and “run riot in the blood of the innocent”. [2]

O’Connell, the charismatic leader of the Loyal National Repeal Association, had always insisted that his movement was non-violent. On the banning of the meeting and the arrival of troops, he frantically moved to call it off and to prevent, “the slaughter of the people”.

The mass meeting at Clontarf was banned the night before it was due to take place and frantically called off by O’Connell.

Handbills were posted around the streets of Dublin advising his supporters of the meeting’s cancellation. A prominent Dublin builder and O’Connell supporter, Peter Martin was sent to Clontarf to dismantle the platform erected there. Other activists were sent on horseback to the roads leading into the city to send back the thousands converging on Clontarf for the meeting.

The following day passed without incident. The Freeman’s Journal raged against the, “corrupt and impotent Government that has perverted the form of law for the purpose of robbing the people”.

The Nation, the more radical nationalist organ, argued, “if it is right to coerce [the Repeal movement] he [Peel] is scandalously to blame for having delayed coercion so long, if it was wrong he is shamefully tyrannical to coerce now.”

The Warder, a Dublin unionist, or as it referred to itself, an “ultra Protestant”, newspaper had been urging the suppression of the O’Connellite mass meetings – “plainly illegal under common law” – for months, “a conclusion at which the government has at length arrived”.[3]

The Warder had only just stopped short of calling for civil war in the run –up to the meeting; “Protestants, what are you doing for yourselves?” , “friends of the British connection must rally round the imperial standard against dismemberment of the Empire, extinction of Protestant religion, destruction of Protestant property, the ruin of the Protestant people of Ireland… unite in self-defence”.[4]

Now it declared itself satisfied. Indeed it congratulated the Conservative government for belatedly seeing sense.

By contrast, the Repeal camp was deeply split. Many, particularly those “Young Irelanders” grouped around The Nation, blamed O’Connell for capitulation to the threat of force and for his unwillingness to confront the British government. They would break from him acrimoniously the following year.

With the cancelling of the Clontarf meeting O’Connell’s strategy of mass mobilisation in pursuit of Irish self government was over. He himself was arrested on charges of “seditious conspiracy” three days later.

But what did Repeal of the Union mean? How did it excite such passions for and against, and how close did Ireland really come to bloodshed in October 1843?

Two warships and 3,000 British troops were sent to Dublin to ensure the rally did not go ahead.

Daniel O’Connell and Repeal

Daniel O’Connell dominated Irish politics for the first half of the 19th century. A member of one of the few Catholic landed families to retain their estates throughout the 18th century, he had been a successful lawyer and then political leader. For his supporters he was the great political champion of the oppressed and for his enemies, a “Popish demagogue”, a “despot” in waiting – ready to mobilise the ignorant Catholic peasant masses to his own advantage.

He was a man of many contradictions. A landlord, who led a movement manned largely by peasant tenantry. An Irish nationalist, who repeatedly voiced his loyalty to the monarch of Britain. A believer in non-violence, who at the time of the rebellion of 1798 was a member of both the government’s Yeomanry Corps and (secretly) the revolutionary United Irishmen.[5]

He saw himself as variously as an Enlightenment liberal, he vigorously opposed slavery for example, an Irish chieftain and leader of the Catholic and Irish people (two groups to whom he tended to refer as one and the same).

In 1822, he had founded the Catholic Association in order to repeal the laws preventing Catholics from holding public office. By means of mass, peaceful mobilisation of Irish Catholics, he had forced the concession of Catholic Emancipation in 1829.

Catholic Emancipation was granted in 1829, O’Connell’s next project was an Irish Parliament, which would have a Catholic majority

His next project was the Repeal of the Act of Union or the restoration of Irish legislative independence. In 1833 he declared, “My plan is to restore the Irish parliament with the full assent of Protestants and Presbyterians as well as Catholics. I desire no social revolution, no social change… In short statutory restoration without revolution…an Irish Parliament, a British connection, one King two legislatures.”[6]

As everyone inIreland was well aware however, an Irish Parliament in the wake of Catholic Emancipation would be a very different proposition from the all-Protestant pre-1801 assembly.

Protestants still dominated land ownership and public positiions but Catholics were becoming more prominent in the professions and in trade

The roughly 800,000 members of the established Church of Ireland owned the vast bulk of the land. Of the 3,033 government jobs in Ireland, the 7 million plus Catholic population held just 134.[7] Order was still maintained by largely Protestant landlords acting as magistrates and the largely Protestant Yeomanry militia carrying out their orders.

Tithes to the Protestant Church were compulsory and resistance to their collection sometimes led to a state of low-level insurrection. In 1832, in the midst of what was known as the “Tithe War”, there were 242 murders in rural Ireland, 300 attempted murders and 568 cases of arson.[8]

The question was, how in a legislature dominated by Catholics, would Protestant privilege be maintained? And if it would not what would replace it?

Not that O’Connell himself was a representative of the toiling masses. O’Connell accepted, in return for Catholic Emancipation, that the electorate in Ireland be reduced sharply from 216,000 to 37,000 men as the property qualification for voting was raised from 40 shillings to £10 per year. The “40 shilling freeholders” who were the bedrock of his support, were sacrificed for rights for the Catholic economic elite.

And the Catholics themselves were not a uniformly oppressed group. In Dublin for instance, they were making inroads into the professions and into trade. In 1840, when the Liberal Under-Secretary for Ireland, Thomas Drummond, reformed the election of Dublin Corporation so that voting was made on the basis of property (of over £10 per year) rather than religion, Catholic voters immediately outnumbered Protestants by over two to one. O’Connell became Lord Mayor of the city in 1841, the first Catholic to hold the position since 1689.[9]

To some extent then, Repeal of the Union was the objective of the Catholic middle class, whose numbers and increasing prosperity would ensure their domination of self-governed Ireland in the post-Emancipation era.

1843 – “The Year of Repeal”

The Repeal campaign gathered momentum in 1842 and 1843

In 1842, a number of events kick-started the Repeal Agitation. One was the defeat of O’Connell’s allies the Liberals by the Conservatives under Robert Peel in Britain. Parliamentary pressure was no longer viable, so O’Connell decided that direct action was needed.

Another factor was the founding of The Nation, a radical nationalist newspaper produced by a group of both Catholic and Protestant liberal activists referred to as “Young Ireland”. The paper sold around 10,00 copies but was thought to have had a circulation of 250,000 and was highly influential in the spread of nationalist ideas.[10]

A third factor was the decision of the Catholic Bishops formally to endorse the campaign in early 1843. Dublin Corporation passed a motion in favour of Repeal in February of that year. O’Connell confidently promised that the government would cave in in the face of mass pressure. 1843, he told his supporters would be the “Year of Repeal”.

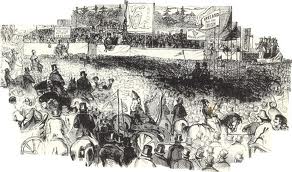

As in the Emancipation campaign, subscriptions were collected in each Catholic parish in support of the Repeal Association. Most spectacular of all were O’Connell’s “Monster Meetings”. Mass shows of strength by the Repeal movement, they were held at historic Irish sites – Tara where the ancient High Kings of Ireland had been crowned, Clontarf where Brian Boru had defeated the Danes in 1014 – and attended by huge crowds, 800,000 in the case of the Tara meeting of August 1843, complete with banners, bands and speeches.

Neither the Tories of Ireland (essentially the hardline Protestant faction) nor the Conservative administration believed that the Repeal Association was really “Loyal” as it claimed, they believed rather that it was simply a front for Irish separatism and perhaps even Catholic agrarian revolution.

But its peaceful character meant that it could not simply be repressed, like, for instance the republican insurrection of 1798 or the agrarian unrest of the 1830s. “The peaceable demeanour of the movement is one of the most alarming symptoms”, the Lord Chancellor, Edward Sudgen wrote to the Prime Minister Peel in May 1843.[11]

The Clontarf meeting was announced by O’Connell on September 4, 1843, to be held “on a mound raised to cover bodies of the Danes who fell in battle there”. It promised to bring up to 1 million people to the capital city in support of the Repeal of theUnion.

Tensions were at the very brink of snapping into violence. The Prime Minister, Peel, ordered all arms in Ireland to be confiscated and sacked Repealer magistrates. The Warder warned of the possibility of massacres of Protestants as in 1641 and 1798 and urged Protestants to arm. It put into the mouths of the Repealers the goal of “In the name of Ireland, VENGEANCE…arise…as you abhor the Saxon tyranny as you revere the memory of the heroes of 1642 and the martyrs of 1798, as you love Ireland and HATE England”.[12]

The pro-Repeal Freeman’s Journal told its readers that, “Your enemies are doing everything in their power to tempt you from the course of peaceful agitation” but urged them not to respond in kind. [13]

The final straw for the government, or the excuse to ban the meeting, depending on where one stood, came when The Nation called for “Repeal Cavalry”, mounted, with military style cockade hats and carrying sticks to attend the Clontarf meeting.[14]

The fact that the notice banning the meeting was published at the very last moment led to accusations that Peel’s government did indeed want to force a confrontation and perhaps even a massacre. The fact that O’Connell backed down was a bitter and humiliating blow to his movement and proof that the tactic of non-violent mass mobilisation could go no further for fear of bloodshed.

What might have been

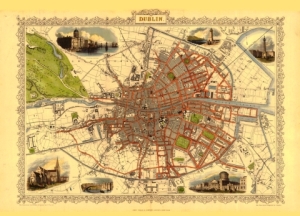

If we want to know what the mass meeting at Clontarf might have been like had it gone ahead, we might look at the Repeal Demonstration of July 4, 1843 by the Dublin Trades Associations.

A Repeal rally in Dublin in July 1843 gives us an idea of what the Clontarf demonstration would have been like

Forty three Trades Associations and several thousand people, assembled at Cabra Road with banners proclaiming “Erin Mavourneen”, “Erin Go Bragh” and “Adeu to Religious Bigotry” and marched from Phibsborough in the north of Dublin, through the city centre to Donnybrook, south of the city.

On reaching Dublin Castle, they sang “God Save the Queen” to show their loyalty and then halted outside the old Parliament Building on College Green, where they gave 9 cheers for Repeal of the Union. Outside Trinity College they exchanged taunts with Tory students, but were asked by their stewards not to be provoked by what the Freeman’s Journal called, “the braying of young asses”.

At his house on Merrion Square, Daniel O’Connell addressed the marchers and told them that after “500 years of unmatched persecution”, “England should give Ireland her rights peaceably and quietly, if not the Irish nation would wring it out of them as it had wrung Emancipation”.

The nationalist press called the day, “a glorious day for Ireland” and praised the “exemplary patriotism and ardour” of the Dublin tradesmen.[15]

The Tory Warder saw events quite differently, complaining that Dublin had been put, “under the military occupation of the army of Roman Catholic Repealers for the space of about four hours”. Protestant businesses, they complained, including the offices of The Warder on Fleet Street, had been closed out of fear of “the mob”.

The Clontarf Meeting would not have forced the granting of Irish self-government but its banning caused the fracture of the Repeal movement

They sarcastically thanked the “Repeal Army”, which “could have hung their editors, yet evinced noble self denial and did not do so! We do not want to be hung”. It called for “extinction of the agitation and punishment of the agitator”, “before it is too late”.[16]

In all likelihood, the Clontarf rally would have been a similar experience on a larger scale – boisterous and exhilarating for its supporters, intimidating for its opponents. By itself it would not have forced Repeal, it was its banning that was decisive.

The wider question of course, is whether, for the vast bulk of Irish people, an Irish parliament at this juncture would have made any difference.

The Great Famine was just two years away. Perhaps an O’Connellite assembly would have reacted more quickly to the crisis, that left over million dead, than the British government did, but given its highly socially conservative nature, it may not have. Nor would it have embarked on extensive land reform.

In any case, whether or not the Clontarf meeting went ahead, there does not seem to have been much chance of either a Liberal or Conservative British government peacefully granting Irish self government.

For all that, its banning marked the fracturing of O’Connell’s movement and the beginning of the end for O’Connell himself. Because of this, it remains one of the great turning points in modern Irish history.

References

[1] Patrick Geoghegan, Liberator, The Life and Death of Daniel O’Connell, 1830-1847, p163

[2] Freeman’s Journal October 7, 1843 (NLI)

[3] The Warder, October 7, 1843 (cites The Nation)

[4] The Warder September 30, 1843

[5] Patrick Geoghegan, King Dan.

[6] Gearoid O Tuathaigh,Ireland before the Famine, 1798-1848, p145

[7] James Murphy,Ireland, A Social Cultural and Literary History 1791-1891, p24

[8] O Tuathaigh, p148

[9] Hill, Jacqueline, The Protestant Response to Repeal, the case of the Dublin working class, in Ireland Under the Union, (Lyons and Hawkins eds), Clarendon 1980. p45-46

[10] O Tuathaigh, p166

[11]Murphy,Ireland 1797-1891

[12] The Warder, April 29, 1843

[13] Freeman’s Journal, October 7, 1843

[14] Geoghegan, Liberator, p162

[15] Freeman’s Journal, July 4, 1843

[16] The Warder

, July 8, 15, 1843