Today in Irish History, Bloody Sunday in Derry, 30 January 1972

T he fatal shooting of 13 unarmed demonstrators by the British Army in Derry in 1972. By John Dorney. See also Four Bloody Sundays.

he fatal shooting of 13 unarmed demonstrators by the British Army in Derry in 1972. By John Dorney. See also Four Bloody Sundays.

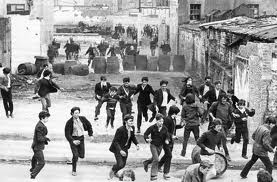

In January 1972, a march was called by Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association in for Sunday January 30th in Derry. Its purpose was to protest against internment without trial, which had been introduced in August of the previous year.

The city was already in a state of low-intensity conflict. Since 1969, when Catholic protests against discrimination within Northern Ireland had exploded into a three day riot with the police known as the Battle of Bogside, British troops had patrolled the streets.

The Catholic working class Creggan and Bogside areas were sealed off with barricades and behind them, in so called “Free Derry“, two rival IRAs, the Officials and Provisionals patrolled in hijacked cars, shooting at any British troops that entered the area. Ten soldiers had died in the city already. Rioting between troops and what they referred to as the “Derry young hooligans” was also a regular occurrence.

Derry was already in a state of low intensity conflict in early 1972, but the mood on the morning of the march was peaceful

The British Army for their part had already shot dead two local youths, Seamus Cusack and Desmond Beatie, in July 1971 whom they accused of being armed, an accusation vigorously denied by locals. Another four civilians were killed by the Army by the start of 1972. As the Saville Inquiry acknowledged, “The situation in Londonderry in January 1972 was serious. By this stage the nationalist community had largely turned against the soldiers.”[1]

All political demonstrations had been banned in Northern Ireland the previous August, “until order was restored” . Nevertheless when the march, on January 30, 1972, started out in the Creggan, as Dr Raymond McClean remembered; “the atmosphere was so relaxed and cheerful that I decided to leave all my equipment in the car in the Creggan as I thought there would be no casualties to treat.”[2]

‘A scoop-up operation’

The RUC Chief superintandant wanted a non-confrontational approach to the march but was over-ruled by the British military commander

The Royal Ulster Constabulary police force (RUC), had if anything an even worse relationship with the nationalist population of Derry at the time than the Army, being seen as the force behind the Protestant domination of Northern Ireland. But had their advice been followed, the march might have gone off as peacefully as Dr. McClean predicted.

The local RUC Chief superintendant, Frank Lagan wanted to allow the march enter the city centre unmolested, to take pictures of rioters and if necessary pick them up later. But since 1969, it was the military who had primary responsibility for public order in Northern Ireland. Major General Robert Ford wanted, by contrast, to oppose the march leaving Creggan and entering city centre, with the intention of arresting “young hooligans” … “a scoop up operation to arrest as many hooligans and rioters as possible”. [3]

He had deployed for the operation one of the British Army’s elite combat formations, the 1st Parachute regiment.

Even more ominously, Ford had recently written a memo to his commander in chief, Harry Tuzo, in which he expressed the view that the minimum force required to deal with the “Derry Young Hooligans” was, “after clear warnings, to shoot selected ringleaders”.[4]

A Bloody Ten Minutes.

Although the march had been banned, it mostly passed off peacefully after Army barricades prevented the 15,000 marchers from leaving the nationalist Bogside and passing into Derry’s city centre.

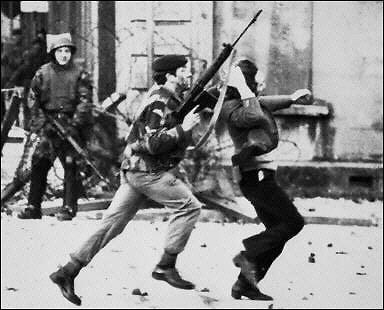

A small number of youths, as was common in Derry in those disturbed times, began to throw stones at the soldiers.

The response of the British troops varied considerably. Some units, the Royal Green Jackets, “acted with restraint”, in the words of Saville Inquiry and used rubber bullets, tear gas and water cannon on the stone-throwers.

Some shots were also exchanged; two soldiers of Machine Gun Platoon, fired between them five shots from the derelict building on William Street– wounding two men. In retaliation a member of the Official IRA fired a rifle at soldiers, without causing casualties.[5]

But it was 1 Para that was charged with “scooping up” large numbers of rioters in arrests. Their Brigadier, MacLellan, gave strict orders for them not to follow the youths down Rossville Street, where they would be mixed up with peaceful marchers. Colonel Wilford, who was directly in charge, failed to pass on this order and sent his Support Company, in armoured vehicles, chasing the rioters down into the maze of terraced streets and flat complexes.

Eamonn McCann a radical Derry leftist who had been behind much of the original protest movement in the city recalled;

The soldiers fired 100 shots from their SLR rifles killing 13 people and injuring a similar number

“When the shooting started that day the first reaction, after fear, was bewilderment. Why were they shooting? At Free Derry Corner where most people had gathered for the meeting, the crowd flung themselves to the ground as the crack-crack of the self-loading rifles came from the bottom of Rossville Street. Looking up one could see the last few stragglers coming running panic-stricken, bounding over the barricade outside the High Flats, three of them stiffening suddenly and crumpling to the ground. One ought to have realized at the time that what was happening was they were being killed.”[6]

McCann’s disbelief was understandable. While the Paras had been sent to Derry to mount an aggressive arrest operation and possibly even “shoot ringleaders”, of the rioters, no one anticipated indiscriminate firing on unarmed crowds. The British soldiers, in an unfamiliar area, surrounded by people they believed to be hostile, were panicked by fire from one of their own officers, named in the Saville report as “Lieutenant N”, who fired over the heads of the crowds to disperse them.

The soldiers, hearing the sound of shots echoing off the surrounding buildings thought they were coming under fire and began indiscriminately to shoot at the people around them. Five died on Rossville Street and the rest were killed as soldiers pursued the fleeing crowds into the neighbouring flat complexes.[7]

McCann again; “An hour and a half later no one knew for certain how many were dead. Some said three, some five. From McCafferty’s house in Beechwood Street Bernadette Devlin phoned Altnagelvin Hospital and asked for the names of the casualties. About 20 people crowded around her into the hallway as she prepared to write them down. The pushing and shoving stopped as she just kept on writing.

[He heard]… how Jacky Duddy had been just behind Father Daly in the car park of the High Flats, laughing to see a priest running when the bullet got him; how Pat Doherty had been lying out in the open moaning, ‘I don’t want to die on my own’, and Barney McGuigan, a big quiet man, had gone out to him waving a white handkerchief and was shot in the base of the skull; how John Young had been dragging himself, wounded in the shelter of the barricade across Rossville Street towards the door of the flats, people screaming down at him, come on lad, come on, you’re nearly there’, but he didn’t make it.”[8]

Dr Raymond McClean, who had set out on the march so optimistically, found himself searching the nearby houses for casualties, “In the first house I found Michael Kelly …and lying beside him Jim Wray [both already dead]… William McKinney… said to me, “I’m going to die doctor am I?” I lied a bit and said ‘you have been hit badly but if we can get an ambulance and get you to a hospital quickly I hope you’ll be alright”.[9]

The shooting had lasted only ten minutes. One company of soldiers from the Support Company of 1 Para Regiment – having stormed into the Bogside in armoured vehicles to arrest rioters – had fired 100 shots from their SLR rifles in and around the flat complexes ofRossville Street, Glenfada Park and AbbeyPark, killing 13 people and injuring a similar number. Most of the dead were young men (only two were over 40) and six were aged 17. The shooting was done by only a handful of soldiers – around ten in total.

At the time, the British troops claimed they had come under sustained attack. The Army statement the following day claimed, “The troops came under nail-bomb attack and a fusillade of 50-80 rounds from the area of Rossville Flats and Glenfada flats. Fire was returned at seen gunmen and nail-bombers. Subsequently, as troops deployed to get at the gunmen, the latter continued to fire. In all a total of well over 200 rounds was fired indiscriminately in the direction of the soldiers. Fire continued to be returned only at identified targets”.[10]

The British government’s Widgery Inquiry of 1972 largely backed up this version, but the subsequent British Saville report of 2010 found, “Despite the contrary evidence given by soldiers, we have concluded that none of them fired in response to attacks or threatened attacks by nail or petrol bombers. No-one threw or threatened to throw a nail or petrol bomb at the soldiers on Bloody Sunday.”

There was some firing from republican paramilitaries of the Official IRA on the day, but, “nothing approaching that claimed by some soldiers and nothing that would justify them opening fire”. The Provisional IRA’s leader in Derry, Martin McGuinness, was “probably carrying a Thompson sub-machine gun” but there is no conclusive evidence that he used it on the day.

Moreover, “With the exception of Gerald Donaghey, who was a member of the Provisional IRA’s youth wing, the Fianna, none of those killed or wounded by soldiers of Support Company belonged to either the Provisional or the Official IRA”. [11]

Consequences

The standard nationalist narrative of Bloody Sunday in 1972 is that it created the Provisional IRA and largely spawned the subsequent conflict in Northern Ireland.

Certainly the event cast a long shadow. Eamonn McCann wrote, “After Bloody Sunday, the most powerful feeling in the area was the desire for revenge. Since the deaths of Cusack and Beattie and the introduction of internment there had been mass support for the IRA, but it had been tempered with a vague uneasiness about the morality of killing people… Now…people made a holiday in their hearts at the news of a dead British soldier.”

Saville wrote, with studied understatement, “What happened on Bloody Sunday strengthened the Provisional IRA, increased nationalist resentment and hostility towards the Army and exacerbated the violent conflict of the years that followed”

Hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of young Catholic men and women were propelled into the ranks of both IRAs, but especially the Provisional IRA, which was gearing up for its armed campaign.

The British Embassy in Dublin was burnt to the ground by irate crowds. The south was awash with belligerent rhetoric, Taoiseach Jack Lynch called the paratroops’ actions, “Incredibly savage and inhuman”. Patrick Hillary, the Irish foreign minister told a New York audience, “my one aim now is to get Britain out of Ireland”. [12]

Originally, the British Army had been deployed inNorthern Ireland as an aid to the civil power and was actually welcomed by nationalists as a more neutral force than the Northern Irish RUC or B-Specials. Now they were shooting down unarmed demonstrators. There could be no better validation of the argument that peaceful protest had run into a wall of repression and armed struggle was the only viable option.

In 1971, 171 peopled were killed in political violence in Northern Ireland. The death toll in 1972, the year after Bloody Sunday, almost tripled to 479 deaths and between 2-300 were killed every year until 1977, after which the rate of killing dropped sharply but continued to hover at or just under 100 a year until the ceasefires of 1994.[13]

The Stormont Parliament of Northern Ireland was suspended, partly in response to the Derry shootings, by the British Government on March 28, 1972 and Direct Rule from London was introduced, which lasted until the new Northern Ireland Assembly was established under the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, in 1999.

Bloody Sunday, tragic event as it was, speeded up the dynamics of a conflict already underway.

Was Bloody Sunday really to blame for all this? A few words of caution are necessary here. The Provisional IRA was already preparing for an onslaught on what it thought of as the British occupation of Ireland. Bloody Sunday gave them more activists and sympathizers but their course of action was already set. The loyalist paramilitaries would have responded as they did, with sectarian killings of Catholics, with or without Bloody Sunday.

The British Army for its part later admitted that in its early years in Northern Ireland, it conducted a counter-insurgency campaign using the methods of colonial wars fought in places such as Aden and Malaysia. In the early 1970s, the Army was too ready to treat the Catholic or nationalist population as the enemy and killed many civilians, mostly Catholic, in these years (though not as many as either republican or loyalist paramilitaries). In a two day period in August 1971, for instance 11 Catholics, this time in Ballymurphy in Belfast were shot dead by the British Army during arrest operations.[14] Another five were shot in Springhill in Belfast in July 1972.

It did learn lessons and killed far fewer people from the late 1970s onwards, but its relationship with the nationalist population was permanently poisoned.

In short, Bloody Sunday, tragic event as it was, speeded up the dynamics of a conflict already underway. Without doubt it contributed to the extraordinary length of the Troubles as well. But the continuation of the killing was also a result of choices taken on all sides.

References

[1] See Saville Report, Eamonn McCann, War and an IrishTown, Pluto Press 1993, p145-146. A total of 19 people had died violently in Derry in the year before Bloody Sunday, all but one since the introduction of internment in August 1971. They were; 10 British soldiers (9 killed by the IRA and one in an accident), 2 RUC officers killed by the IRA, six Catholic civilians shot by the British Army and one IRA member killed by the British Army. CAIN chronology.

[2] Patrick Bishop Eamonn Mallie, The Provisional IRA, Corgi 1988, p207

[3] Bishop, Mallie, p206

[4] Saville report

[5] Saville report

[6] McCann, p157

[7] Saville report

[8] McCann, p157-158

[9] Bishop, Mallie p 208

[12] Coogan p161

[13] Conflict Archive on the Internet,University ofUlster.