‘One skilled scientist is worth an army’ – The Fenian Dynamite campaign 1881-85

Shane Kenna delves into the background of the Fenian bombing campaign in England in the 1880s.

What they aspire to and what they declare openly they have sworn to obtain, is not merely the repeal of the Union, but the establishment of a perfectly independent Irish Republic… they therefore declare that the only method of obtaining their ends is by frightening England and the English people. Until at last [England] shall be only too glad to let Ireland go her own way:[1] The rational and motivation of the Fenian Dynamite Campaign

Terrorism is an act of political violence seeking to coerce political elites, through the intimidation of public opinion, into yielding ground on a political grievance. A central plank of terrorist strategy, therefore, is the attacking of soft rather than hard targets – using the bomb as the language of political grievance.

Terrorism is an act of political violence seeking to coerce political elites, through the intimidation of public opinion, into yielding ground on a political grievance. A central plank of terrorist strategy, therefore, is the attacking of soft rather than hard targets – using the bomb as the language of political grievance.

This is done to instil a sense of terror through the psychological effect of the bomb, which is used to cause widespread and arbitrary destruction in urban centres. The Fenian bombing campaign in London of 1881-85 was an early example of this tactic.

Following the failure of advanced nationalism in the 1860s and especially the abject failure of the rebellion of 1867 and of the raids on Canada in 1866 and 1870, American Fenianism was riven with disillusionment; many activists perceived a period of revolutionary paralysis with no plan of campaign to counter the British presence in Ireland.[2]

This feeling of despondency was further underlined by recognition that successful Irish rebellion required congenial circumstances, which all regarded as non-existent. Coming to this conclusion, many frustrated and aggrieved Fenians decided to wait for a moment favourable to insurrection; they strategized that this would be facilitated byBritain becoming embroiled in a global conflict, diverting military attention from Ireland.

Such a strategy, however, could only justify stagnation, and apparent humiliation for Fenian ambition, with the movement ‘consigned to the melancholic bar room reminisces of the increasingly aged men of ’67.’[3] Against this strategy, militant firebrands, particularly the youth, very much disillusioned by the lack of revolutionary direction, were desirous of undertaking direct action to meet the British presence in Ireland with uncompromising resistance by whatever means expedient.[4]

Irish American Fenians embarked on the dynamite campaign in response to the organisation’s lack of direction in the 1880s

This was representative both of a perception that the conditions for Irish revolution were non-existent, and that the Victorian interpretation of warfare as two recognisable armies and a defined code of conduct was impractical under Irish conditions.

The phenomenon of modern terrorism originated in the nineteenth century. In this narrative attention has been particularly given to Russian revolutionaries and their desire to secure political change through violence, directed against political elites rather than the public. Within studies of terrorism fleeting attention is paid to Fenian terrorism, and where it is, it is often deprecating and inequitable.[5]

In fact, Fenian bombers revolutionised the concept of terrorism in the nineteenth century. Terrorism in an Irish context was pioneered in the Fenian dynamite campaign between 1881-85, when Irish-American Fenianism undertook a sustained terrorist campaign incorporating a series of explosions in British urban centres. For the first time in British history, through an integrated use of explosives and timers, utilising modern technology, the Irish question was not confined to Ireland but now affected daily life in British cities through the unprecedented experience of political violence.

This dynamite campaign was planned, organised and funded by Irish-Americans, taking advantage of advances in modern science and technology, together with the increasing globalisation of Victorian society.

For the first time in history, Fenian bombers had the real ability to transcend national boundaries and, using innovative techniques such as employing explosive timers and detonators – they revolutionised the concept of terrorism, changing it from one of irregular attacks against political elites to a sustained campaign designed to establish public terror in order to coerce policy makers.

The purpose of this article is not to provide a chronological outline of the Fenian dynamite campaign, nor to examine the circumstances of any particular Fenian bombing. Instead, this article will seek to investigate the rationale and motivation behind the Fenian dynamite campaign as a proactive strategy amongst Irish-American Fenians.

A Terrorist Strategy

Many Irish-American Fenians sought a vindication of their struggle by undertaking a recognisable terrorist strategy in Britain while the heavier work of preparing for rebellion was undertaken in Ireland. This strategy required financial support and the Fenians endorsed the idea of a revolutionary fund to prepare, equip and perfect a strategy designed to inspire terror in British cities.

With this in mind, in September 1875 it was suggested in a letter to Patrick Ford, editor of the radical New York Irish World newspaper, that Fenianism should employ a strategy supported by a national fund to mount direct political violence against Britain so as to ‘keep the faith alive’. This strategy was to be underlined by ‘terror, conflagration, and irretrievable destruction’[6] of British symbolic property, while preparation for rebellion actively continued in Ireland.

This fund was to become known as the ‘skirmishing fund’ and increasingly became a rallying point for ‘a general desire to have more life infused into the Irish national movement’[7] by Irish-American Fenianism.

Support for terrorism was not widely endorsed, amongst Irish-American Fenians however. Those who favoured ‘open and honourable warfare’ were incensed by the call for terrorism, believing it dishonourable. This opinion was underlined by the interpretation of warfare in the Victorian era and the belief that terrorism risked bringing Fenianism into international disrepute. In this regard the founder of Fenianism James Stephens recalled the suggestion as ‘the wildest, the lowest and the most wicked conception of the national movement’.[8]

The use of terrorist tactics was not popular among older Fenians, James Stephens called it, ‘the wildest, the lowest and the most wicked conception of the national movement’

The Fenian opponents of a terrorist strategy were repulsed by the concept of irregular and arbitrary terrorism in Britain and stressed the importance of waiting for British difficulty which would draw attention and resources away from Ireland, facilitating the opportunity for open rather than secretive warfare.[9]

Underlined by scientific and technological advancements, however, Irish-American supporters of terrorism will argued that favourable conditions for Irish revolution needed to be fostered by an aggressive campaign justifying the mobilising and symbolic power of violence, rather than waiting for an opportune moment of British difficulty.

A further consideration in the evolution of Fenian terrorism amongst Irish-Americans was the pervading belief in the ability of political violence to coerce British political elites to consider the Irish question. This belief was represented by the veteran Fenian John Devoy at the height of the Fenian dynamite campaign, when he lamented how no serious consideration of Irish political grievance could be won from Britain unless it was ‘wrung from her fear’.

Similarly, Patrick J. Tynan, the notoriously self-proclaimed No. 1 of the Fenian Invincible conspiracy, believed only the threat of force caused ‘more terror and panic to the British heart’, [10] believing the Irish question ‘must be decided by force, or else there is the certainty of national death’.[11]

Precedents for the dynamite campaign

That political violence could coerce the British government to consider Irish grievance was a real possibility, and had been graphically demonstrated already.

In 1867 London Fenians had tried to mount a rescue of an imprisoned leader Colonel Ricard O’Sullivan Burke from London’s Clerkenwell Prison. Their plan had been to penetrate the prison wall with gunpowder explosive to enable Burke’s escape.[12] Using too much gunpowder, however, they had blown down some sixty yards of prison wall, killing twelve people and injuring over one hundred others. While the Clerkenwell explosion was not an act of terrorism but a bungled rescue attempt, contemporaries recalled how ‘terror took possession of society’.[13]

Against this background of rising terror, William Ewart Gladstone, the British Prime Minister, had publically remarked how the explosion had convinced him to address the Irish question, by means of his declared mission to pacify Ireland. This would effectively result in the disestablishment of the minority Anglican Church of Ireland and the introduction of Gladstone’s first Land Act.

The Clerkenwell explosion of 1867 demonstrated the potential of a bombing campaign in England.

Importantly, however, it had demonstrated how an act of political violence had forced the Government to yield ground on the Irish question, as one commentator lamented how Gladstone had ‘appealed to the most potent power in changing English public opinion – the fear of force. The dread of an Irish war, which might easily spread to England’.[14] Recognising how this public admission and the Prime Minister’s gesture of yielding ground to Irish grievance could influence the Fenian belief in the efficacy of political violence, Sir Robert Anderson, a Home Office Fenian expert recalled:

It was their crime… that brought that question within the sphere of practical politics. Even if his estimate of the business had been just, his words respecting it would have been none the less unjustifiable. For they could not fail to encourage Fenians to commit crimes of the same character.[15]

The Irish-American Context

This belief in the ability of political violence to coerce British political elites ran parallel to a pervading political grievance against the place of British rule in Ireland amongst Irish-American Fenians.

Many resented leaving Ireland, believing themselves to have been ‘frozen out of their native land’,[16] holding an enflamed grievance and desire for revenge against colonial rule.[17] This antipathy was cross-generational, its nationalism made more extreme by the weaning of their children on stories of tyranny and of a country held by force, deceit and bribery, underlined by acts of unrelenting cruelty and despotism.[18]

These ‘bitter memories harboured by Irish-Americans, of the Anglo-Irish landlordism and resentment against the British government’,[19] were intensified by contemporary difficulty in Ireland. 1878 and 1879 had seen a poor Irish harvest and failure, the worst on record since the Famine, and increasing emigration and eviction not witnessed on a scale since the 1840s.[20]

In this period Irish-America was strongly reinforced by a wave of new immigrants, many of whom had been forced off the land due to poverty, lack of employment or eviction. These immigrants to the USA carried with them new stories for Irish-America to hear, stories often sensationalised by the Irish-American press, strengthening existing Irish-American belief in British misgovernment. This further tended to consolidate an inclination to violent retribution amongst Irish-Americans.

To many Irish American Fenians, the dynamite campaign was a legitimate response to the coercion of land agitation in Ireland

Combined with the established horrific tales of the earlier famine, the immigrants’ stories illustrated for many the callousness of the British hegemony in Ireland. Irish-Americans were particularly interested in burgeoning land agitation in Ireland and the increasing proliferation of tenant defence leagues. They concluded that landlordism was ‘was the last link which keeps Irelandbound to England’ [21] and as the cornerstone of British rule, which should it be removed, British Rule would be severely weakened.

The Irish coercion legislation to put down land agitation between 1882-83 was therefore widely seen as provoking a legitimate armed response. Coercion was seen within the narrative of American republicanism as the imposition of tyranny justifying a resort to arms in defence of liberty. Thus, during increasing land agitation and coercion in Ireland, Irish-America concluded that something must be done in solidarity with and defence of the whole nation.[22]

A new age of warfare

A further consideration in the evolution of Irish-American Fenian terrorism was the contemporary experience of the American Civil War. In this regard it was evident that the American Civil War had redefined the nature of contemporary warfare, particularly regarding both the use of new technology and the role of civilians.

The Civil War had illustrated the increasing adoption and adaptation of new technology, together with an increasing acceptance of the concept of attrition and willingness to encompass the loss of civilian life. This was recognised by a pamphlet written by Bernard Janin Sage in the middle 1860s, The Organization of Private Warfare – Bureau of Destructive Means and Measures. Sage had cited the need for irregular warfare and the employment of bombs against civilian and symbolic targets, to be organised by ‘bands of destructionists and captors.’[23]

The American Civil war saw the development of mines and booby-trap bombs used against both soldiers and civilians. The post war years saw a stream of terrorist incidents.

Using technological development the Confederates introduced landmines and clockwork explosives. It was well remembered how Gabrial J. Raines, a Confederate General at Yorktown, had sought to delay a Union advance by means of land mines, while the Confederate Secretary of War, George Wythe Randolph, had concluded that the use of explosives and skirmishing was legitimate for genuine military value.[24]

This was represented by the Confederate John Maxwell using what he termed a horological torpedo, a prototype time bomb, disguised as a Candle box and deposited at Union headquarters Virginia, causing over three hundred casualties. Such weapons designed to cause terror and demoralisation were widely used by the confederacy nearing the end of the war, and their destructive potential was understood by contemporary Americans:

The rebels have done all human ingenuity could desire to fix traps for our men. In Some places you will see an overcoat laying on the ground, but it will not do to pick it up, for to it is attached a string leading to a fuse containing powder, so when the garment is picked up it causes the powder to explode and by this means destroy our men. Torpedoes are covered with dirt in the street and should horse or man step upon one it is death.[25]

Other soldiers recalled similar experiences citing how the Confederacy had violated the understanding of modern warfare by relying on explosives designed to ‘kill five or six men every time they did anything or moved anything.’[26]

Such tactics clearly undermined the established rules of warfare and proved that technology and irregular combat had revolutionised conflict distinguishing modern warfare from previous conflict.

In this new recognisably modern warfare there was clearly an acceptance that, through the application of new technology, that antagonists were willing to encompass loss of civilian life and heavy destruction, giving rise to the suggestion of ‘violence against public targets,’[27] which sought to demoralise and dislocate the enemy. Similarly the Union had also studied the adoption and application of new technology in warfare, prepared to undertake a war of ‘protective retribution,’ whereby a similar war of exhaustion could be undertaken against ‘enemy civilians and economy.’[28]

Thus in the American Civil War both sides had utilised the benefits of technological and scientific development, believing that the side which forsook the advantages of modern technology risked defeat at the hands of ‘a less morally fastidious opponent’.[29]

The experience of Civil War further represented a gradual awareness that Generals and strategists were ‘compelled to yield first place in importance to the scientific skill.’[30] In the aftermath of the Civil War a culture of terrorism representative of the escalating proliferation of weapons and explosives used for political advancement and grievance was continuously evolving.

Domestic terror

One contemporary despaired of this terrorist culture, recognising ‘a decidedly unpleasant industry for the construction of infernal machines’ in American cities resulting from technological development.[31] There was a steady stream of bombing incidents, facilitated by the extensive availability of cheap scientific journals to the common man, facilitating the home manufacture of explosives by individuals rather than factory production by chemists and scientists.

As early as 1873 when the New York City Financial Comptroller Andrew H. Green received a prototype parcel bomb, apparently by people aggrieved by Tammany Hall corruption,[32] as did Judge Samuel D. Morris, the former District Attorney, and opponent of official corruption at his residence in Brooklyn on New Year’s Eve, 1873.[33]

In 1874 an Edward Wagner had tried to murder his mother-in-law using an improvised parcel bomb at Philadelphia. The bomb, filled with gunpowder, contained fifty matches arranged to touch a sliding lid and detonate the explosive.[34] In April of the following year, communicants receiving confession discovered a bomb in the vestibule of St. Xavier’s church, Cincinnati. Fortunately it was discovered and thrown outside, where it detonated with ‘a terrific noise’[35]

Two months later an attempt was made upon the lives of the ladies temperance association at Illinois when a bomb was placed under a streetcar.[36] While in 1875, as part of a semi-official vendetta against Jessie and Frank James (the notorious James Brothers), their mothers home was attacked with a bomb thrown through her kitchen window, seriously injuring her and killing their young step-brother.[37]

But the clearest anticipation of the Fenians’ methods came on 28 October 1876, when a time-delayed bomb exploded in the luggage carriage of the express train from Philadelphia to Jersey City. Bearing remarkable resemblances to a future Fenian bomb at Victoria Station London, the device was arranged with a pistol tied to clockwork, which, upon reaching a set time the pistol would discharge detonating the bomb. In the following police investigation it was suspected that the bombers had sought to wreck the train, and its passengers.[38]

That the bomb was used regularly in post-Civil WarAmerica, tends to indicate that in this culture of terrorism inspired by the experience of Civil War and technological development, it had been perceived as a tool of political advancement and a means of settling grievance.

This culture of terrorism provided disillusioned Fenian activists with a contemporary argument for the use of technology to instil a fresh impetus in place of revolutionary paralysis, operating within the norms of post-Civil War America. It was therefore evident that, conditioned by this culture of terrorism and inspired by the experiences of the Civil War, the Fenians recognised terrorism as a viable strategy.

The technology of terror

The final and most important influence upon the adoption of Fenian terrorism was modern scientific and technological development, particularly the invention of dynamite, which tended to encourage a perception of revolutionary equilibrium with the great Powers:

Dynamite was being much talked of in the newspapers; and it was said that the anarchists and nihilists of the old world had at last in their hands an implement of destruction sufficient to destroy all the armies and navies in existence… it was referred to in glowing terms as the gift of science to the oppressed children of men, whereby despotism could be overcome and the sunshine of liberty would illuminate forever more.[39]

Modern scientific and technological development had therefore given the revolutionist, for the first time in history, a tremendous individual and low-cost power perceived as a weapon of the weak, offering unbridled destruction and melodrama in a collective revolutionary delusion.[40]

This perspective was graphically represented by the prominent Irish-American Fenian and Illinois Congressman John F. Finerty who declared: in this struggle, this vendetta, which England has now distinctly challenged, SCIENCE… must match itself against STRENGTH… In this our battle for vengeance and for liberty, one skilled scientist is worth an army’.[41] As a perceived weapon of the weak, modern science had provided the means of constructing explosives in backrooms, kitchens and workshops using cheap and easily-accessed materials common in everyday trade. All that was required, therefore, was a basic understanding of chemistry, facilitating what one contemporary lamented as ‘the new and mighty enginery of destruction which modern science [had] furnished’.[42]

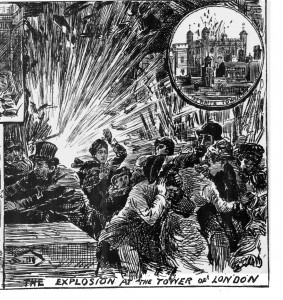

The aim of the campaign was, ‘the destruction of British life and property’, it culminated with bombs at Westminster and the Tower of London

The importance of modern scientific and technological development upon the Fenian impetus for terrorism was graphically illustrated by the establishment of a Brooklyn dynamite school. Under the instruction of O’Donovan Rossa and a supposed Russian specialist known as Professor Mezzeroff (who was, in fact, an Irishman named variously as Smith or Rodgers) students were taught the do-it-yourself manufacture of explosives.

Inspired by the perceived efficacy of modern scientific and technological development, the purpose of this dynamite school was to train men in the do-it-yourself use of explosives in America, and then to dispatch them to Britain to undertake terrorist attacks in British cities.

By the early 1880s at least four of these students were in operation in Ireland, Scotland and England, the most remarkable being Timothy Featherstone, John Francis Kearney, Henry Dalton and Thomas J. Mooney. This new departure meant that explosives would now be built in backrooms, kitchens and workshops using the afore-mentioned cheap and easily-accessed materials, in British cities, with graduates sharing their knowledge with Fenians operating in Britain, seeking ‘the destruction of British life and property’.[43]

The Campaign

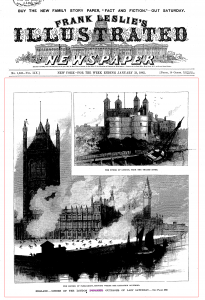

This campaign meant that from January 1881 to January 1885 the Fenians mounted a series of explosions in British urban centres, aboard public transport and – in the red letter event of their campaign – successfully detonated near-simultaneous explosions in the Tower of London, Westminster Crypt and the Chamber of the House of Commons on 24 January 1885 in an event immortalised as ‘Dynamite Saturday’.

This campaign meant that from January 1881 to January 1885 the Fenians mounted a series of explosions in British urban centres, aboard public transport and – in the red letter event of their campaign – successfully detonated near-simultaneous explosions in the Tower of London, Westminster Crypt and the Chamber of the House of Commons on 24 January 1885 in an event immortalised as ‘Dynamite Saturday’.

In the course of their campaign they successfully established an air of fear and paranoia amongst the British public. By their choice of targets indicating their desire to disrupt the common experience of daily life by introducing fear into the simplest everyday experience.

In total twenty men would be arrested for their involvement in Fenian bombings. These men would suffer unbearable Victorian prison conditions, and several of those imprisoned would suffer insanity. One of them, Denis Deasy would die in custody. Thomas James Clarke, the future signatory of the Easter Proclamation and himself imprisoned for involvement in the Fenian Dynamite Campaign, recalled of their jail experience:

Had anyone told me before the prison doors closed upon me that it was possible for any human being to endure what Irish prisoners have endured in Chatham Prison, and come out of it alive and sane, I would not have believed him.… We treason-felony prisoners were known as… the ‘special men,’… kept, not in ordinary prison halls but in penal cells- kept there so that we could be more conveniently persecuted, for the authorities aimed at making life unbearable for us. The ordinary rules regulating the treatment of prisoners, which, to some extent, shield them form foul play and the caprice of petty officers, these rules as far as they did that, were in our case set aside… This was a scientific system of perpetual and persistent harassing… harassing morning, noon and night, and on through the night, harassing always and at all times, harassing with bread and water punishments, and other punishments with ‘no sleep’ torture and other tortures. This system was applied to the Irish prisoners and, to them only, and was specially designed to destroy us mentally or physically – to kill or drive insane. [44]

Conclusion

Fenian terrorism did not originate from Ireland but was peculiar to a culture of terrorism inherent to post-Civil War America.

To conclude, the Fenian terrorist strategy was, essentially, rationally chosen and underlined by a perceived revolutionary paralysis following the failure of the previous decade. Terrorism thus provided a practical argument for rejuvenation necessary to instil a fresh impetus within defeated Fenianism. Underlined by developments in science and technology, Fenian terrorism did not originate from Ireland but was peculiar to a culture of terrorism inherent to post-Civil War America.

It had evidently been influenced by the pervasive Fenian belief in the ability of political violence to coerce British political elites to consider and address Irish grievances. This had been graphically represented in the aftermath of the Clerkenwell explosion when the Prime Minister had been seen to be coerced into yielding ground on the Irish problem.

Furthermore, technological development paralleled to the escalating proliferation of weapons and explosives being used for political advancement and grievance by ordinary Americans was undoubtedly a key motivation in the Irish-American impetus for terrorism.

The Dynamite Campaign had been made possible through the innovative use of technology and an obvious desire to attack symbolic targets in urban centres. Its legacy, however, remains that for the first time in British history the Irish question would not be confined to Ireland but would affect British urban centres and sensibilities, reaching and touching not just the political elite but the very people themselves.

References

[1][1] Anon, ‘Dynamiters in Paris,’ in The Gentleman’s magazine and historical chronicle (London, 1886) p. 370.

[2] Draft of John Devoy’s recollections, John Devoy Papers, NLI Ms 18,014.

[3] Kelly, M.J. The Fenian Ideal and Irish nationalism 1882-1916 (Woodbridge, 2006), p. 15 & see also Short, K.R.M., The Dynamite War – Irish-American Bombers in Victorian Britain (Dublin, 1979), p. 35.

[4] The Irish World, 4 March 1876.

[5] Ibid.

[8] [8] Quoted in The Special Commission Act, 1888 – Report of the proceedings before the commissioners appointed by the act, Vol. IV (London, 1890) p. 189 and Davitt papers TCD, MS 9659d

[9] [9] The Irishman, 27 March 1880.

[10] [10] Tynan, Patrick, The Irish National Invincibles and their times (London, 1894) p. 26.

[11] [11] Tynan, Patrick, The Irish National Invincibles and their times (London, 1894) p. 32.

[12] [12] Denvir, John, The Irish in Britain from earliest times to the fall and death of Parnell (London, 1892) p. 243.

[13] [13] Anderson, Sir Robert, Sidelights on the Home Rule movement (London, 1906) p. 77.

[14] [14] Tynan, Patrick, The Irish National Invincibles and their times (London, 1894). 25

[15] [15] Anderson, Sir Robert, Sidelights on the Home Rule movement (London, 1906) p. 79.

[16] [16] Bagenal, Philip, The American Irish and their influence on Irish politics (London, 1882) p. p. 218.

[17] [17] Crenshaw, Martha, ‘the causes of terrorism,’ in Comparative politics 13:4 (July, 1981) p. 394.

[18] [18] Henry, George ‘An American view of Ireland,’ in Nineteenth Century: A Monthly Review, 12:66 (August, 1882) p. 177

[19] [19] Draft of John Devoy’s recollections, undated, NLI Ms 18,014

[20] [20] Moody, T.W., Davitt and the Irish Revolution, (Oxford, 1982) p. 564.

[21] [21] Bagenal, Philip, The American Irish and their influence on Irish politics (London, 1882) p. 201. See also Victor Drummond to the Earl Granville, 12 August 1881 TNA FO 5/1779 and Robert Clipperton to the Earl Granville, 1 November 1881, TNA FO 5/1780

[22] [22] The Irish World, 4 December 1875.

[23] [23] Sage, Janin, Bernard, Organization of Private Warfare – Bureau of Destructive means and measures: Bands of Destructionists and Captors, Reprinted in William A. Tidwell, April ’65: Confederate Covert Action in the American Civil War (Kent, 1995) pp. 205 -212.

[24] [24] Tidwell, William A, April ’65: Confederate covert action in the American Civil War (Kent, 1985) p. 91.

[25] [25] Notes of Lieutenant Hyde, 21 May 1900 in History of the Fifth Massachusetts Battery (Boston, 1902) p. 245

[26] [26] Letter of Peleg W. Blake, 5 May 1862 in History of the Fifth Massachusetts Battery (Boston, 1902) p. 244.

[27] [27] Larabee, Ann, ‘A brief history of Terrorism in the United States,’ in Knowledge, Technology & Policy, Volume 16, No.1 (March 2003) p. 27

[28] [28] B.M. Linn ‘The American Way of War revisited,’ in the Journal of Military History, 66/2 (2002) p. 510.

[29] [29] C.B. Sears quoted in B.M. Linn ‘The American Way of War revisited,’ in the Journal of Military History, 66/2 (2002) p. 514.

[30] [30] John Schofield quoted in B.M. Linn ‘The American Way of War revisited,’ in the Journal of Military History, 66/2 (2002) p. 515.

[31] [31] The New York Times, 6 January 1874.

[32] [32] The New York Times, 27 November 1873.

[33] [33] The New York Times, 5 January 1874.

[34] [34] The New York Times, 21 July 1874, & also 23 July 1874.

[35] [35] The New York Times, 22 April 1875.

[36] [36] The Galveston Daily News, 4 June 1874.

[37] [37] The Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, 2 February 1875.

[38] [38] The New York Times, 28 October 1876.

[39] [39] Stephens, James, Fenianism: Past and present [undated], The James Stephens papers NLI Ms 10, 492 [6]

[40] [40] Brown, Terence, Irish American Nationalism (New York, 1966) p. 72

[41] [41] The Citizen, 22 December 1883 TNA HO 144/1537/1.

[42] [42] Seelye, Julius H. ‘Dynamite as a factor in civilisation,’ in The North American Review, Vol. 137, No. 320 (July, 1883).

[43] [43] Pierrepoint Edwards to the Home Office and Foreign Office, 16 August 1882 Fenian A Files A730 and see also Robert Clipperton to the Earl Granville, 9 May 1882, Fenian A Files A716, Robert Clipperton to the Earl Granville, 3 April 1883, TNA FO 5/ 1861 & Pierrepoint Edwards to the Home Office and Foreign Office, 16 August 1882 Fenian A Files A730.

[44] Clarke, Thomas, Glimpses of an Irish Prison Felons Life (Dublin, 1922).