The All-for-Ireland League 1909-1918

Many familiar with Irish history of this period are more than aware of the centrality of the Home Rule Party, as Conor Mulvagh has explained elsewhere on this site. Here John O’Donovan looks at the IPP’s rival, the All for Ireland League.

Many familiar with Irish history of this period are more than aware of the centrality of the Home Rule Party, as Conor Mulvagh has explained elsewhere on this site. Here John O’Donovan looks at the IPP’s rival, the All for Ireland League.

As we embark on the ‘Decade of Commemorations’, it will be important that due attention is paid to the sidelines of the narrative, to examine aspects of Irish life which may not fit easily with the Yeatsian narrative of 1890-1916 being a “featureless valley”.

The Irish Parliamentary Party were seen by many (including their own supporters and Members of Parliament) in this period as the only expression of Irish constitutional nationalism; but for all that they represented the mentality of the majority of bourgeois and petit-bourgeois Irish nationalists, the Party did not have a monopoly on Irish constitutional nationalist political representation.

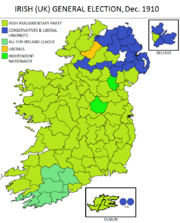

In the 1910 election the All For Ireland League won 8 seats

At the general election of December 1910 the Irish Party won 73 of 83 nationalist seats in Ireland. Two of the remaining seats – North Westmeath and South Monaghan – were won by Laurence Ginnell and John McKean respectively[1]. The others, based entirely within the county of Cork, were held by members of the All-for-Ireland League (AFIL).

The All For Ireland League and IPP differed primarily on the question of relations between nationalists and unionists in Ireland. They also differed on the question of land redistribution. In essence, the AFIL argued for state-funded transfer of land facilitated by friendly agreements between tenants and landlords as opposed to confrontation. On the question of self-government, O’Brien and his followers were in favour of gradual steps along the road to a parliament in Dublin. In 1911 O’Brien argued for full dominion status for the island of Ireland within the British Empire; it was a decade before this term resurfaced in nationalist political debate.

The roots of the AFIL

The AFIL represented the culmination of many years of agitation by O’Brien, a journalist, newspaper proprietor and MP for Cork city (1892-5; 1900-18, with interruptions). Together with a coterie of mostly Cork-based followers, O’Brien had, since 1902, championed the cause of conciliation with firstly landed unionists, and latterly with all Irish unionists.

Through an organisation, the Cork United Irish League Advisory Committee (CUILAC), he and his followers maintained a highly critical view of the Home Rule Party and its grassroots political organisations. While the CUILAC maintained an independent stance, and supported people and organisations inimical to the majority of Nationalists, O’Brien himself believed that he and his followers were true inheritors of the conciliatory legacy of Parnell.

O’Brien maintained that by rejecting the methods which had brought about the Wyndham Land Act of 1903 (that is conciliatory conference between nationalist and unionist representatives on matters of common concern), the Party leadership, (John Redmond, John Dillon, T.P. O’Connor and Joseph Devlin) had abrogated their responsibilities towards the Irish people. Furthermore, O’Brien argued that persistent fixation with the issue of Irish self-government had blinded the Party to other beneficial legislation which could be obtained; for example, in the area of education and in reform of the poor laws.

Thus, he argued, by a process of gradual cooperation in areas of common concern – which O’Brien believed stretched beyond the land question – nationalists and unionists would be able to agree on some form of self-government for the island of Ireland as a whole.

AFIL founder William O’Brien favoured conciliation with landlords for land reform and with northern unionists over Irish self-government

This message did not find favour with the majority of Party leaders, MPs or supporters. It is arguable whether O’Brien’s methods were targeted for special opposition because of their potential to upset the social status quo or if it was a clear clash of nationalist ideology. Certainly the ‘Ranch War’ of 1904-8 was a clear signal that the Party and its agrarian grassroots, through the United Irish League (UIL), rejected the notion of conciliatory negotiation with local landlords in favour of a campaign of cattle rustling and intimidation –methods which were designed to force the Liberal Government of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman to introduce a new Land Act enshrining the principle of compulsory land purchase.

In 1907 nationalists rejected Irish Chief Secretary Augustine Birrell’s Irish Council Bill, which had offered a very limited self-government for Ireland. O’Brien had been in favour of the Bill, even suggesting to Birrell how the Council should be structured and offering suggestions as to what areas of Irish administration it should control. William O’Brien had rejoined the Irish Parliamentary Party by this point, however, he was out of the country for health reasons when the Bill was rejected by an IPP Convention in May 1907. Thereafter, self government having again been postponed, in the short term, the Party focussed once again on the land question.

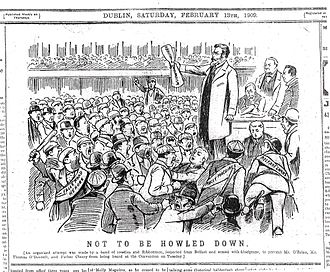

The implementation of the 1903 or Wyndham Land Act was impeded by the almost total failure of the legislative machinery set up under the Act and a new land bill was introduced by Chief Secretary Birrell in 1908. The internal Party debate over this Bill saw O’Brien and his followers split from the Party again in April 1908. Ten months later, O’Brien was shouted down, and his followers physically attacked, at a Party Convention in Dublin’s Mansion House which had been called to debate, among other things, the new Land Bill.

Those who drove O’Brien out of the convention were mainly members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) and followers of Joseph Devlin, MP for West Belfast. The AOH had been reorganised under the presidency of Joe Devlin from the early 1900s, and had fought a long and bitter battle with the Catholic hierarchy in the North of Ireland until receiving the approval of Patrick O’Donnell, Bishop of Raphoe in Co Donegal and the IPP’s chief Episcopal ally.

Thereafter, as Devlin worked his way up the ranks of the IPP and the UIL (becoming the League’s General Secretary in 1905) the AOH gained in influence and power. Having fought (literally in many cases) to preserve the Catholic religion in Ulster, Devlin and his allies including Denis Johnston were not afraid to use ‘strong-arm’ tactics to quell opponents. This brought the condemnation of many nationalists, including Cardinal Michael Logue of Armagh, who decried the, ‘organised system of blackguardism’. All For Ireland League supporters labelled all IPP supporters as ‘Molly Maguires’, a term referring to the underground secret society in the United States with whom the AOH was associated.

O’Brein and his followers disliked the influence of the Ancient Order of Hibernians in the Irish Parliamentary Party and derisively nicknamed them the ‘Molly Maguires’ – after a violent Irish-American secret society

Parallel to these developments, O’Brien’s chief organiser in Cork, Daniel Desmond (DD) Sheehan had been fighting a battle within the organisation he co-founded in 1894, the Land and Labour Association. The LLA represented rural workers, the lowest stratum on the pyramid of Irish rural society. By 1906 this organisation had split with the Irish Party and the UIL; on one side stood Sheehan and his supporters, on the other stood James J O’Shee, MP for West Waterford and clear Redmond supporter. O’Shee disaffiliated branches of the UIL he felt had become ‘politicised’ i.e. supported Sheehan and O’Brien versus the Party.

In retaliation Sheehan formed the Irish Land and Labour Association (ILLA), which by 1909 had taken on the de facto role of an O’Brienite organisation – the equivalent of the UIL for the Irish Party. It was under the aegis of the ILLA that a large crowd gathered on 21 March 1909 in the market town of Kanturk in north-western County Cork. At the subsequent meeting O’Brien and Sheehan spoke, each elaborating on the programme of the new party to become known as the All for Ireland League or AFIL.

Founding the AFIL

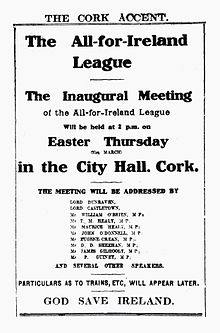

Formal notice of the founding of the AFIL came after a final meeting of the CUILAC in Cork city on Thursday 24 February 1909. At the meeting a number of delegates were selected to meet O’Brien and negotiate ‘as to the future of the National movement.’ That evening the delegates, as well as Sheehan, Eugene Crean (MP for Cork South-East and a prominent labour personality in Cork city), plus Fr Denis O’Flynn (O’Brien’s strongest clerical supporter in Cork city) met O’Brien at Turner’s Hotel in the city centre. At the conclusion of the meeting, a statement was issued to the press:

‘A private conference of Cork Nationalists of all shades of opinion was held on Thursday night … It was unanimously resolved to found a new movement, to be called the ‘All-for-Ireland League.’

The main object will be ‘to unite on a common platform all Irish-born men in a spirit of the broadest toleration of differences of opinion between brother Nationalists, and of scrupulous [sic] respect for the rights and feelings of their Protestant fellow-countrymen, with a view to concentrating the whole force of Irish public opinion in a movement to obtain self-government for the Irish people in Irish affairs.’

Its further purpose will be to develop kindlier spirit, patriotism, and co-operation among Irishmen of every rank and creed in all projects for the National welfare in which common action may be found practicable.

These projects are declared to be primarily the completion of the abolition of landlordism on just terms at the earliest practicable date, the active promotion and extension of the movement for the revival of Irish industries, the cultivation of the language, traditions, and ideals of the Gael, and the social and intellectual elevation of our industrial, agricultural and labouring population both in town and country.’

The following week, O’Brien’s newspaper the Irish People published front-page cartoon visually representing the message and goal of the AFIL.

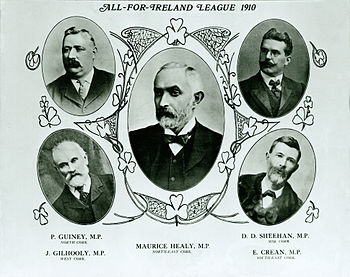

However, the AFILs progress was stalled with the sudden departure of O’Brien from Ireland at the end of March 1909, due to serious illness. In the period between April and December 1909 the AFIL existed in name only, as no formal organisation was created, although the by-election in Cork City brought about by O’Brien’s resignation as MP saw Maurice Healy – former MP for the city and brother of Tim – successfully win the seat under the AFIL banner. The concomitant closure of the Irish People left the AFIL without a press champion; faced with national opposition from the Party-aligned Freeman’s Journal and local hostility from the Cork Examiner (whose proprietor George Crosbie was the defeated Party candidate in the by-election won by Maurice Healy), the League existed as an almost underground movement.

By the autumn of 1909 a general election was inevitable, as the Liberal government of Hebert Asquith (who succeeded Campbell-Bannerman as Prime Minister in 1908) came under increasing pressure from both Irish Parliamentary Party and Tory MPs, though (it should be stressed) not in coalition.

William O’Brien did not wish to fight the election, nor become the organising figurehead of the AFIL. He told John Forde in Cork city that he would support the League financially and morally, but his physical condition precluded his taking an active part in politics. Alarmed, Forde conferred with Fr O’Flynn, Sheehan, Crean and a few local leaders, and reported to O’Brien that it was essential for the survival of the AFIL as a political force that he stand for election. Reluctantly, O’Brien agreed; this decision gave a boost to the anti-Party cliques operating in all Cork constituencies.

The elections of 1910

The violent elections of January and December 1910 confirmed the depth of Irish Party hostility towards O’Brien and the AFIL, inside and outside Cork. Cork was the scene of many violent outbursts between the elections, which were occasioned by the ‘Constitutional Crisis’ caused by the rejection by the House of Lords of David Lloyd George’s ‘People’s Budget’ in 1909. AFIL and IPP supporters clashed in Cork city, Bandon, Kinsale, Bantry, Newmarket, Charleville, Kanturk, and other towns and villages.

In Mayo, riots were witnessed in Ballina, Claremorris and Crossmolina, where revolvers were fired into the crowd. Serious rioting also occurred in Newmarket in May and Bantry in August; in the former the RIC fired into crowds of feuding gangs, killing a young rural labourer; in the latter a UIL rally was assailed with stones, sticks, mud, eggs and tar macadam, and the RIC were attacked with batons and stones.

The 1910 election saw serious rioting and even shots fired between AFIL and IPP supporters

In the interval between the two elections, the AFIL was formally launched in Cork city on 30 March 1910. Membership cards were commissioned, and inscribed with verses penned by nineteenth-century Romantic poet and nationalist Thomas Davis (like O’Brien a native of Mallow) which concluded with the words:

“All for Ireland here are we,

All for Ireland’s liberty,

To right, to raise, to set her free,

Our Native Land forever.”

The AFIL elected a committee, with James Gilhooly (MP for West Cork and a veteran of the 1867 Fenian Rising) as President; William MacDonald (chairman of Cork County Council) as Chairman; DD Sheehan as Secretary; and Fr O’Flynn, Michael Ahern, Forde and Edward Fitzgerald of Mallow (a solicitor and O’Brienite who had represented Gilhooly and Sheehan in court cases over the previous decade) as ordinary members of the committee.

The League did not found branches or have a Parliamentary Party, but Sheehan’s ILLA acted as the former, and a loose federation of MPs including O’Brien, Tim Healy, Maurice Healy, Gilhooly, Sheehan, Crean, Patrick Guiney (MP for North Cork) gave Westminster representation to the AFIL. In the style of the Independent Irish Party of the 1850s, the AFIL MPs signed a pledge to act and vote together on questions of land redistribution and self-government legislation. On other areas, however, MPs were allowed complete freedom to act and vote as they saw fit.

The December 1910 election, called after the collapse of a conference between Tories and Liberals on the question of the House of Lords veto, was a severe test of the strength of the AFIL. Although the League performed well in Cork city and county, capturing the second seat in Cork City and ousting Party MP Edward Barry in South Cork, it over-stretched its resources in trying to unseat Party MPs in Kerry, Limerick and Mayo. Other AFIL-supported candidates in Wexford, Armagh and Dublin, where solicitor James Brady (an O’Brien contact dating back to the years of the Irish People) tried to ally the AFIL and Arthur Griffith’s Sinn Féin movement, were routed.

A curiosity emerged in North-East Cork, where Moreton Frewen was elected unopposed as the AFIL MP. Frewen was given the seat by O’Brien, possibly in return for his alleged access to financial resources and his claim that he was in close contact with officers of both the Conservative and Ulster Unionist parties. This led the anti-O’Brien press, led by the Freeman and more remorselessly DP Moran’s The Leader, to mock the AFIL, labelling the organisation as the ‘Frewenites’.

The AFIL in parliament

O’Brien was painted as a dupe of landlords and their political representatives, and stories emerged of his attending dinners at the Kildare Street and Cork County Clubs organised in his honour. While it is true that O’Brien, like many bourgeois Nationalist politicians, did mimic the lifestyle of the landed gentry (receiving addresses when arriving to live in houses, being feted when visiting local hospitals and orphanages, etc.) he probably maintained too much integrity to allow this affect his professional life and work.

To publicise the work of the AFIL, and to spread its message, O’Brien, Lord Dunraven and a number of his contacts established a daily newspaper in Cork city in February 1910. In June this paper, the Cork Free Press, published its first issue with a lengthy and hard-hitting editorial written by the parish priest of Doneraile and author of popular fiction, Canon PA Sheehan. Sheehan welcomed the decline of the Protestant Ascendancy, but railed against the building up of a Catholic Ascendancy on its ruins. Ireland, he claimed, had the potential to become a greater power than England, if she would cease, “estranging and expelling her own children, and turning them … into her deadliest enemies.” The first editor of the Free Press was John Herlihy, the English son of Cork immigrants to London, who had been editor when the Irish People closed down in 1909.

With the passing of the Parliament Act in early 1911, the AFIL encountered its first test as a political entity operating within the sphere of Westminster politics. The Act removed the power of the House of Lords to veto any bills passed by the House of Commons; a direct consequence of the Constitutional Crisis which had led to the two general elections in 1910.

The AFIL rejected the 1912 Home Rule Bill due to its failure to accommodate the concerns of Ulster unionists and because it contemplated the partition of Ireland

From an Irish perspective, the passage of the Act brought the Home Rule question firmly back into the spotlight, as all previous attempts to legislate for Irish self-government had foundered on the rocks of Tory peer hostility in the House of Lords.

O’Brien and the AFIL were convinced that for any Home Rule legislation to succeed, it should be framed in such a way as to take into account the wishes and concerns of the minorities on the island of Ireland – specifically the Protestant unionist community in the north. Through the period 1911-14 the AFIL put forward counter-proposals to those favoured by the Asquith government and the IPP. It proposed a system of federalism, or ‘Home Rule all round’, whereby each nation in the UK would receive a parliament with certain devolved powers. This solution was also championed by many southern Irish unionists, including O’Brien’s close contact Lord Dunraven. A probationary Home Rule settlement was also tabled, whereby Ireland would receive a parliament for five years, after which a review would determine whether the experiment should continue.

Unionist actions and protests against the Government of Ireland Bill introduced in 1912 escalated in 1913 with the formation of the UVF and the Irish Volunteers. In response, the AFIL held a large convention in Cork city in March 1913, passing a resolution calling on all parties involved to accept a settlement by consent. This did not deter the opponents of the Bill, and the Free Press condemned the leadership of the IPP for goading the Ulster Unionists into taking up arms.

In May O’Brien addressed an AFIL rally at Charleville where he referred to the Bill as “no more a Home Rule than [IPP MP Joe] Devlin’s Parliament is Grattan’s Parliament”; the AFIL, he declared, “can no longer pretend to accept this maimed and crippled Bill as a final and unalterable settlement”.

The AFIL and the Home Rule Crisis

By the autumn of 1913 Asquith and his cabinet recognised the seriousness of the opposition to Home Rule in Ulster, and began to formulate plans to exclude certain portions of the north-east of Ireland from the terms of the Home Rule Bill. In October Asquith spoke with characteristic vagueness that he was “open to consider any scheme for the adjustment of the position of the minority in Ireland subject to governing considerations”, which the AFIL took to meaning that the “Conciliation policy … still holds the field”.

Other senior figures in both the Tory and Liberal parties urged Ulster Unionists to broach the subject of Home Rule by Consent, a cause championed almost on a weekly basis by the Free Press. At the end of October Tory leader Andrew Bonar Law accepted an invitation to confer with Asquith, which the Free Press trumpeted as a victory for the AFIL. The meetings, however, seem to have been less about achieving a full Home Rule settlement by consent than how best to broach the subject of exclusion with hardliners in both parties.

Redmond’s position as IPP chairman throughout 1913 was under constant if inconsistent attack from the AFIL. Tim Healy – who had been re-elected to Parliament in 1911 after the resignation of Moreton Frewen – derided Redmond as a ‘political blanc-mange’, liable to jump from one position to another in the space of a few days. At the start of 1914, with the likelihood of civil war approaching by the week, Redmond reluctantly agreed to the exclusion of certain parts of Ulster from the provisions of the Bill.

This brought about paroxysms of rage from the AFIL; the Free Press thundered that “the whole conduct of the Molly Maguires is sufficient to make us believe that they … are ready to betray the ideal for which the Irish people have battled for a thousand years with all the tenacity of their race.” Canon Sheehan’s posthumous novel, The Graves at Kilmorna, with its characterisations of an Ireland run by corrupt Party organisations, and where an idealistic ex-landlord fails to succeed in running for office, is possibly a requiem for the AFIL viewpoint at this time.

The spectre of the partition of Ireland, followed by civil war, was overtaken by events in Europe in the summer of 1914. Outbreak of war forced a cessation in domestic hostilities, with the Home Rule Bill placed on the statute book but suspended until after the war’s conclusion. The two years between 1914 and 1916 saw a melting of the AFIL’s support; many supporters either joined the Army to fight in the war or, rejecting O’Brien’s appearance on recruiting platforms, became members of more radical anti-war nationalist organisations.

The Easter Rebellion in Dublin in 1916 was portrayed by O’Brien as a surprising but logical consequence of the rise of sectarian nationalism. Government reaction to the Rebellion saw the closure of the Free Press. The paper, having gone through a number of editors since Herlihy’s resignation in 1911, had by the time of its demise become a hotbed of Sinn Féin activity, encouraged by its final editor Frank Gallagher. Gilhooly’s death that year necessitated a by-election in West Cork, which descended into farce, allowing IPP candidate Daniel O’Leary to steal the seat. This tragicomedy was the last active participation by the AFIL in popular politics.

Surviving in name only as many of its branches had dissolved or become centres of local Sinn Féin activity, the AFIL was invited to participate at the Irish Convention in 1917. O’Brien and Healy declined to attend, arguing that the composition of the Convention had made its outcome inevitable. By this time partition had become almost certain and O’Brien would not be a party to Lloyd George’s scheme for such an outcome. In 1918 a Home Rule proposal made it to the floor of the House of Commons, but was linked with a conscription bill. This ‘conscription crisis’ led to the final withdrawal of the AFIL from the House of Commons.

The end of the AFIL and its legacy

The radicalised nature of Irish politics and society in 1917-18 led to O’Brien and the rest of the AFIL MPs standing aside in favour of Sinn Féin in the December 1918 general election

The radicalised nature of Irish politics and society in 1917-18 led to O’Brien and the rest of the AFIL MPs standing aside in favour of Sinn Féin in the December 1918 general election. Rumours circulated that some AFIL members, due to their open support for the British Army in Cork, were forced to leave the country; these have not been substantiated to any great degree. O’Brien’s final address to the electors of Cork spoke of his and the AFIL’s support for “the spirit of Sinn Féin, as distinct from its abstract programme … and accordingly they ought now to have a full and sympathetic trial for enforcing the Irish nation’s right of self-determination.”

In its afterlife, the AFIL continued to have influence on the character of the new twenty-six-county Irish state. The radical labour movement that provided much of its grassroots formed the nucleus for both the Labour Party (which subsumed most of the rural labour organisations) and Fianna Fail, especially in Cork city. William O’Brien endorsed FF shortly before his death, and Fianna Fail Taoiseach Jack Lynch’s father was an O’Brien supporter through his union.

Although the AFIL was a fragmented, fractious organisation, the spirit through which it was founded, grew and ultimately died held a powerful attraction for a significant minority of Irish nationalists. This spirit of independent nationalist thought and action did not peter out with the demise of the AFIL. Its legacy to Irish history and politics is important, and understated.

Through this brief outline of its history, it should become clear that the AFIL encompassed a wide variety of Irish political strata, and as such is worthy of further study.

Sources

Patrick Maume: The Long Gestation: Irish Nationalist Life 1891-1918 (Dublin, 1999)

Alan O’Day: Irish Home Rule, 1867-1921 (Manchester, 1998)

Joseph V O’Brien: William O’Brien and the Course of Irish Politics 1881-1918 (Berkeley and London, 1976)

Paul Bew: Ideology and the Irish Question: Ulster Unionism and Irish Nationalism 1912-1916 (Oxford, 1994)

D George Boyce and Alan O’Day (editors): The Ulster Crisis 1885-1921 (Basingstoke, 2005)

John O’Donovan is a Cork-based historian and a graduate of UCC. His chief research interests are: Irish history 1890-1916, rural labour history, grassroots political movements in Ireland 1879-1921, the United Irish League, history of Cork City and County 1890-1921. You can read his blog ‘Turbulent Cork’, here.

[1] McKean was nicknamed ‘Congo Jack’ after his denunciations of reported Belgian atrocities in the Congo, later proved by Sir Roger Casement)