Belfast Riots – A Short History

In recent articles on the Irish Story, Brian Hanley has looked the effects of the 1935 Belfast riots on southern Ireland. This is a short introduction into the history of civil strife in Belfast. By John Dorney.

The riot has played a significant role in Irish history and nowhere more than in the northern city of Belfast.

Rioting elsewhere has commonly been between demonstrators of various kinds and state forces – whether British, Irish or Northern Irish. Where state forces have lost their control and deployed lethal force against unarmed rioters – Bloody Sunday in Derry in 1972 or the Yeomanry massacre of 12 farmers resisting payment of tithes in Wexford in 1831 for instance – this kind of street battle can turn into massacre. But generally, the discipline imposed on police or army personnel and the lack of weapons of rioters limits the bloodshed in these type of confrontations.

Belfast, of course has seen this kind of rioting too, but in that city, almost uniquely on the island, there has existed since the mid 19th century two large and often antagonistic working class communities (Catholic/nationalist and Protestant/unionist), pressed right up against one another. This factor has given Belfast riots an especially bloody and disruptive character.

In the worst Belfast riots, anyone of the ‘opposing’ religion could be a target and on some occasions thousands of people have been forced from their homes and jobs. The neutrality of state forces in the city between the two factions was also an issue, particularly after control over policing was handed to the new Northern Ireland authorities in 1922.

‘No Surrender, No Pope’

Belfast in the late 18th century was a liberal, predominantly Presbyterian merchant town. Presbyterians were still discriminated against by law – marriages by their clergy, for instance, still did not have legal status until the mid 19th century and many northern Presbyterians were attracted to United Irish republicanism in 1790s. For several years in the 1790s enthusiastic parades took place in July in Belfast, not to commemorate William of Orange’s victory at the Boyne in 1690 but the fall of the Bastille in Paris in 1789.

But all this changed in the first half of the 19th century. For one thing Irish nationalism under Daniel O’Connell became more directly associated with Catholicism. O’Connell himself discovered the effect this had on northern Protestants on a visit to Belfast to promote the Repeal of the Union cause in 1841 when he was chased away by shower of stones and by some 6,000 Presbyterians shouting, “No Surrender!” and “No Pope!”. A complex mixture of the repression of the 1798 insurrection, fears of sectarian atrocity arising from it and fears for industry outside of the Union with Britain had transformed Belfast from radical hub into Conservative fortress by the 1840s.

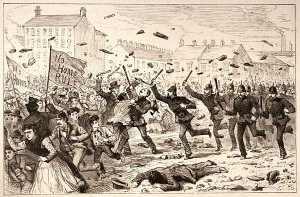

The urban geography of Belfast had also changed as the city (for city it now was) became industrialized. Catholics from rural Ulster flocked to Belfast in search of work and set up their own neighbourhoods, predominantly in the west of the city. In response working class Protestants were attracted to militantly loyalist groupings. Riots erupted over the banning of Orange parades in 1829. Dublin ‘Ultra Protestant’ (his term) evangelical preacher Tresham Gregg set up a Belfast Protestant Operative Association to defend ‘Protestant Ascendancy and the British Empire’ and that group along with the Orange Order led sectarian rioting against Catholic Repealers in July of 1843. Serious disturbances also occurred in 1857, 1864 and 1872.

In the 18th century Belfast was a liberal Presbyterian city. Sectarian rioting began in Belfast in the late 1820s

So already by the mid 19th century, two prominent features of Belfast rioting were in place – clashes in west and central Belfast along the sectarian ‘frontier’, often sparked by political controversies over Irish independence and flare ups in July in and around the parades of the Orange Order. To this must also be added, by the late 19th century, economic competition between the Catholic and Protestant working class – particularly in city’s shipyards.

All of these elements were present in Belfast’s bloodiest riot in 1886. On June 8, the first Home Rule Bill (which would have granted Ireland a devolved parliament) came before the House of Commons. In the event, it was defeated, but that did not stop as many as 50 people losing their lives in Belfast over the coming weeks. Trouble reportedly started with a Protestant worker being expelled from his job at the shipyards by Catholic Home Rule supporters on June 4. Protestant workers, led by a preacher named ‘Roaring’ Hugh Hanna in retaliation beat ten Catholic workers so badly they were put in hospital and drowned another in the River Lagan, with another 200 Catholic shipyard workers being forced from their jobs.

Violence quietened for a time after the Home Rule Bill’s defeat but flared up again after the July 12th Orange parades provocatively marched through Catholic areas, and raged until September. The Royal Irish Constabulary (most of whose men were Catholics) found themselves fighting both sides, but especially the Protestants and suffered at least one dead – a superintendant – and 390 injured. At least thirteen of the fatal civilian casualties were Protestants shot dead by the police and British military.

Belfast’s bloodiest riot of the 19th century came in 1886 with the first Home Rule Bill

Many Julys after 1886 would see both tensions in the shipyards and fighting, including stone throwing and even gunfire, along what is now called the sectarian ‘interface’. In 1893 when a second Home Rule Bill was put before the British Parliament police baton-charged loyalist protestors and Catholics were again expelled from the ship-building jobs. The same occurred in 1912. When trying to promote the Third Home Rule Bill in Belfast in that year, Winston Churchill was nearly lynched by a Protestant crowd outside Celtic Park football ground. July of that year predictably saw another flare up.

The first Troubles 1920-22

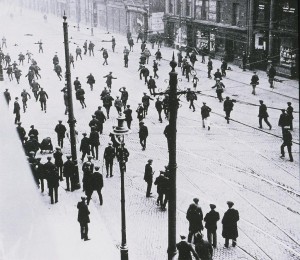

But it was the dark period of 1920-22 – a period that spanned the Irish War of Independence and the creation of Northern Ireland – that saw the worst Belfast rioting of the early 20th century. From the summer of 1920 to the autumn of 1922, political violence in Belfast cost 465 people their lives, with over 1,000 wounded.

This conflict was begun with two bouts of rioting in 1920. The first came (again) in July when after the killing of a northern police officer in Cork, loyalists (many of them unemployed ex-servicemen from the Great War) marched on the city’s shipyards to expel Catholic workers and also “rotten Prods” – or left-wingers who were assumed not be sufficiently anti-Catholic. As many as 7,000 were chased from their jobs. In the little slum streets of west and central Belfast, volleys of shots and stones were exchanged, 22 people were killed and hundreds wounded.

Riots in Belfast in 1920 saw 7,000 workers expelled from their jobs. Subsequent street riots resembled low intensity warfare

Just over a month later on August 22, when another northern detective was assassinated by the IRA in Lisburn, there followed another ten days of sectarian violence in Belfast, with another 33 deaths. The rioting of this period resembled low-intensity warfare more than civil disturbances at times. ‘Belfast’s Bloody Sunday’ of July 10, 1921 for instance – in which 16 people were killed, 70 injured and 200 homes destroyed, saw the use on both sides (now organised into paramilitary groups) of rifles, machine guns and hand grenades as well as the customary stones and clubs.

From this period also grew a great distrust between the Catholic population of Belfast and the new Northern Ireland security forces – the Royal Ulster Constabulary and the Ulster Special Constabulary – who unlike their predecessors in the RIC were almost wholly Protestant and unionist and who on a number of occasions carried out, in uniform, reprisal killings of Catholics. With the defeat of the IRA in the North by late 1922, violence, including rioting, eventually petered out.

However, disturbances would again erupt from time to time in Belfast in the 1920s and 1930s. Some of these incidents –such as the 1932 Outdoor Relief riots actually saw Catholics and Protestants demonstrate (and fight) side by side in protest at the cutting of unemployment assistance. Depressingly often, however, violence would resume the old sectarian pattern.

In 1935, after several months of rising tension, riots broke out during the Orange parades on 12th July. Over the next week, 2,000 people, mainly Catholics, were forced from their homes, Catholics were driven out of workplaces and several were killed in sectarian attacks. The majority of the 11 people killed in the 1935 riots were Protestants, but most of those forced from their homes (86%) and injured were Catholic.

1969 and after

The following decades were relatively placid in Belfast with exception of a major riot in 1964 when police tried to remove a tricolour flag from Sinn Fein office in Divis Street.

The next large scale outbreak of civil strife in Belfast came in August 1969 in rioting that was the harbinger of nearly 30 years of sustained though low-intensity conflict in Northern Ireland. In response to rioting in Derry arising out of, on one side Civil Rights agitation by Catholics and the Protestant Apprentice Boys Parade on the other, nationalists in Belfast staged protests outside RUC police stations.

Blame for what happened over the following two days must be shared. There was provocation from the nationalist side, some shots were fired at police and a grenade thrown by an IRA member (see Hanley, Millar, The Lost Revolution p126), leading the Northern Ireland authorities to think they were facing an insurrection. But undoubtedly it was the authorities’ response that helped to utterly alienate the city’s Catholic population from the state.

RUC armoured cars equipped with machine guns fired on the Catholic Divis Flats killing a six year old boy, while further up the Falls Road, police failed to stop a loyalist crowd from burning down two terraced streets in Catholic neighbourhoods. Eight people were killed over three days and 750 injured. Barricades went up. Rival paramilitaries patrolled their areas. The British Army was deployed with fixed bayonets to restore order – a move Catholics initially welcomed.

In August 1969, the RUC fired machine guns at Catholic flats and was believed to have let Protestants burn out two Catholic streets.

The rioting that scarred Northern Ireland for the following thirty or so years thereafter shared many facets with what had gone before. Trouble generally flared in July or at moments of great political tension -such as the introduction of internment in 1971 or the Hunger Strikes of 1981. It usually broke out in areas where Catholic and Protestant communities bordered one another – between the Shankill and Falls roads in west Belfast, around the Catholic enclave of Short Strand in east Belfast and around Ardoyne in the north of the city.

As before, houses were burnt and families expelled from their homes on both sides. By the 1990s such de facto segregation had been solidified by the construction of ironically titled ‘peace walls’, separating the warring sides. Most of these are still in place today – preventing mass incursions into rival neighbourhoods but also hardening segregation of daily life.

One factor which became less prominent in Belfast rioting by the 21st century was competition over jobs. As the city lost its industrial base (in common with other cities like Glasgow and Newcastle) the previous Protestant dominance in working class employment became irrelevant. The Peace Process of the 1990s meant that rioting, though it still occurred; saw less paramilitary involvement and less use of guns.

Nevertheless events of December 2012 and January 2013 – where loyalists have demonstrated, often violently , against the majority-nationalist city council’s vote to remove the Union flag from Belfast city Hall, complaining that the British character of the city was under threat and that the police (now the Police Service of Northern Ireland) were not impartial, could be described in much the same words as the events of 1886.

The demography of the city has changed. Catholics are now a slight majority. As yet, however, the latest street violence has thankfully not taken on an inter-communal character.

One would hope these disturbances are an echo of the past and not a sign of the future.