‘An Abundance of First Class Recruits’, The GAA and the Irish Volunteers 1913-15

Richard McElligott on the Gaelic Athletic Association and the founding of the Irish Volunteers.

The recent centenary of the formation of the Irish Volunteers celebrated what is undoubtedly a seminal moment in Irish history. The establishment of the Volunteers represented the militarisation of Irish nationalism, a process that inevitably lead its most extreme faction to seize the opportunity presented by the Great War to rebel in Easter 1916.

Writing on the Volunteers has frequently illustrated, quite rightly, the importance of the Gaelic League in spurring its development in local areas. Yet too little consideration has been given to the equally pivotal role played by the Gaelic Athletic Association. This article will illustrate that in many areas, most notably county Kerry, the GAA became the driving force behind local Volunteer organisation.

This was only natural. In 1913 the GAA was easily the largest and most influential nationalist body in Ireland and given the age profile and political outlook of the majority of the GAA’s membership, it represented an ideal recruiting ground for the Volunteers.

‘Prowess have been proved on many a hard fought field’

With the Home Rule crisis of 1912 the Unionist majority in North East Ulster, under the leadership of Edward Carson, established a militia force calling itself the Ulster Volunteers. Its aim was to oppose the introduction of Home Rule by force if necessary. In response to this threat to Ireland’s aspirations of self-government, Eoin MacNeil urged that Irish nationalists should follow the Ulster Volunteers’ example and create a similar force to protect their right to Home Rule.

Following this, Maurice P. Ryle, editor of the Kerry Advocate newspaper, delivered a speech in Tralee and declared, ‘[I]f Ulster can give him [Carson] 90,000 drilled men, what could not the rest of Ireland be able to give’. Ryle stated that members of the GAA ‘whose prowess have been proved on many a hard fought field’ could easily form volunteer clubs and drill in the use of arms.

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) was equally worried about the potential of such a force, commenting that if it was established ‘the Gaelic Athletic Association could supply an abundance of first class recruits’.

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) was equally worried about the potential of such a force, commenting that if it was established ‘the Gaelic Athletic Association could supply an abundance of first class recruits’.

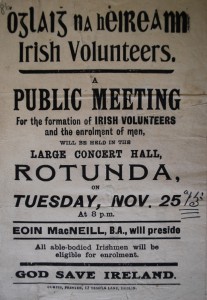

Their fears proved justified. On 22 November 1913 a large public meeting was held in the Rotunda in Dublin city at which the Irish Volunteers were formally established. Jack Shouldice a member of Dublin GAA County Boardwho attended the meeting, subsequently recalled that around a third of those present in the crowd were GAA men.

Across Ireland the Volunteers spread rapidly, as nationalists, determined that Home Rule be realised, filled the ranks to protect its implementation from Unionist aggression. In areas like Kerry local GAA officials were immediately prominent in setting up the organisation. Tadgh Kennedy, a member of the Kerry County Board, was contacted by the Volunteers in Dublin and asked to arrange a meeting to discuss the formation of a corps in Tralee.

Members of the GAA ‘whose prowess have been proved on many a hard fought field’ could easily form volunteer clubs and drill in the use of arms. Maurice P. Ryle.

Kennedy enlisted the support of the Kerry GAA president, Austin Stack, to organise the assembly. Thomas Slattery, a former president of the Kerry GAA, chaired the meeting at the Tralee Town Hall on 10 December 1913, at which a branch of the Irish Volunteers was established while Diarmuid Crean, the Kerry Board’s secretary, acted as the meeting’s secretary. But Kerry was by no means unique. J.J. Walsh, the President of the Cork GAA, became a leading figure within the Cork City Volunteers while Harry Boland, the Chairman of the Dublin GAA, was heavily involved with the formation of the Volunteers in the capital.

Events during the spring of 1914, most notably the Curragh mutiny incident and the Larne gun-running episode, resulted in an explosion in the Volunteers’ membership. Enlistment in the force rocketed from 27,000 in April to 180,000 that June. At this time John Redmond, the leader of the Irish Parliamentary party, moved to secure control over the rapidly expanding force. As the Volunteers became more widespread and started to recruit young and active men, it was inevitable that a large proportion of its members would be drawn from the GAA.

The politics of GAA members in the Volunteeers

The extent of this dual membership only increased as the Volunteers grew. Yet, it is hard to determine the loyalties of those GAA members who enlisted to the opposing strands of nationalism, and how much the infiltration of the Volunteers by radical elements, such as the Irish Republican Brotherhood, had affected them.

Certainly, a majority fully supported the constitutional nationalism embodied by Redmond. His recent achievement of securing Home Rule on the statue books at Westminster had only increased his own prestige and that of his party.

A a majority of GAA members in the Volunteers in 1914 supported the constitutional nationalism embodied by Redmond.

Yet at an official level, the relationship between the Volunteers and the GAA remained ambiguous. Central Council, the GAA’s governing board, refused the Irish Volunteers permission to use Croke Park for drilling purposes in December 1913. Colonel Jeremiah J. O’Connell, in his unpublished account of the Irish Volunteers, was of the opinion ‘that the Volunteers did not receive the help they expected from the G.A.A., and to which later on they might fairly be considered entitled’.

In a letter to the Gaelic Athlete, a member of the Volunteers complained that while in the previous year the Association had held a successful national tournament in aid of a memorial to their deceased patron, Archbishop Thomas Croke, they were now failing in the more pressing duty of holding a national tournament to help raise funds to arm the Volunteers. The writer noted that most of their provincial leaders were prominent members of the GAA and they should use their influence to get the GAA to provide funds.

Despite this, at the GAA’s Annual Congress in 1914, Robert Page, representing the Executive of Irish Volunteers, obtained leave to address the delegates. He stated that like the GAA, the Volunteer movement ‘was a purely National body, non-political and non-sectarian, though they were more a militant body. They did not ask Congress to take any official action, but they asked delegates when they went back to their clubs to recommend the objects of the Volunteers movement’.

The GAA leadership stepped back from endorsing the Volunteers, not being prepared to risk the Association’s popularity as a sporting body through open political commitment

Notwithstanding this, the Association’s leadership stepped back from endorsing the movement and it was clear that the Central Council was not prepared to risk the Association’s popularity as a sporting body through open political commitment. Yet, as has been shown, this did not stop prominent GAA officials from identifying themselves with the movement. In January 1914, James Nowlan, the Association’s president, addressed a crowd of GAA members in Wexford and recommended that every member should ‘join the volunteers and … learn to shoot straight’. Meanwhile, one of the speakers at the inaugural meeting of the Irish Volunteers in Dublin had been the GAA’s secretary, Luke O’Toole.

A characteristically patriotic attitude – GAA members in the Volunteers

Despite the Association’s cautious approach to the Volunteers on a national level, locally in areas like Kerry there was a significant degree of interaction. When a corps was formed in Castleisland in April 1914, James McDonnell, the County Board’s vice-president, John Collins (the Kerry football team trainer) and J.M Collins (the Kerry football team coach) were prominent in the attendance.

John Moran, the County Board’s treasurer, was a member of the Listowel Volunteers committee. In Castlegregory, Kerry’s star midfielder Pat O’Shea was instrumental in forming a volunteer corps and stated that the local GAA club was used extensively as a recruiting ground for members.

In Killarney, Eugene O’Sullivan, the former president of the Dr.Crokes club, addressed several Volunteer rallies while Dick Fitzgerald, the Kerry captain, was an officer in the Killarney corps.

At a meeting of the Kerry Board in March 1914, its secretary, DiarmuidCrean, was reported to have made a stirring speech putting forward the claims of the Volunteers to the delegates present. The Kerry Board also argued for a greater degree of co-operation between the two organisations.

At a Board meeting that September Michael Griffin, who had become prominent in the Listowel Volunteers, proposed a resolution requesting that the Central Council summon an immediate national convention. He suggested that at this convention the Association should amend its constitution to allow for the affiliation of rifle clubs in the same manner as hurling and football clubs were affiliated. He also recommended that the Central Council should promote rifle competitions among the GAA’s membership. The National Volunteer,the official journal of the Irish Volunteers, declared that the Kerry GAA:

has done excellent work in furthering the idea of rifle competitions under the auspices of the Gaelic Athletic Association, and we trust that the characteristically patriotic attitude of the Central Authority will do everything possible to make the new move a success … Kerry, true to its traditions, has made a good start, and has indicated the proper co-ordination of the Volunteers with Ireland’s national pastimes. It was, of course inevitable that sooner or later the G.A.A should play a conspicuous part in regeneration of Ireland, and the golden opportunity is at hand.

The National Volunteer itself was widely supportive of the GAA and carried a dedicated weekly Gaelic Games column. Yet while in areas like Kerry the Volunteer movement was wholeheartedly espoused by the GAA, this was not uniformly the case nationally. Cornelius Murphy, a Volunteer from Cork, recalled that only around 10% of GAA there had any involvement with the local Volunteers.

Despite the caution of the GAA leadership, there was a significant crossover in member ship between the GAA and the Volunteers

He himself played for two GAA clubs and stated when the Volunteers started he was the only member of either who joined up. Colonel Jeremiah O’Connell also wrote that while many of the Volunteers’ best officers were captains of GAA teams, the athletic activities of such men too often conflicted with their military duties and ‘when a match and a parade or a field day clashed too often the parade or field day was put into the background’.For example in Clare in 1914, the first county inspection of the Volunteers was delayed for a week as it clashed with the All-Ireland hurling final which Clare was contesting.

Nevertheless, the relationship between the Volunteers and the local GAA continued to grow. The blurring lines of political nationalism were evident when the Kerry footballers travelled to New Ross for a match with Wexford in June 1914. Over 22,000 attended the eagerly anticipated clash which was the centrepiece of a two day Gaelic League Fheis and Industrial exhibition in the town. Diarmuid Crean, in his role as county secretary, used the match as cover to secure a shipment of arms for the Tralee Volunteers.

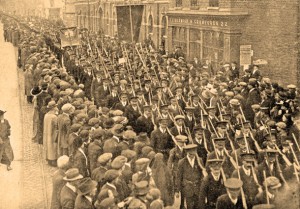

Meeting the Volunteers’ Director of Arms, Michael O’Rahilly he was able to purchase twenty to twenty-five rifles from him, for a sum of £200. As membership soared, Irish Volunteer companies became more and more prominent at local Gaelic Events. That July, a re-match between Wexford and Kerry was organised in Tralee. When the train carrying the Wexford team arrived in Tralee around 700 Volunteers were drawn up outside the station. Once they emerged from the station, the Wexford players were conveyed to the positions allotted to them in the ranks of the Volunteers. A torchlight procession headed by the local Volunteer band marched them through the town to the team’s hotel.

The 1914 Split

By now an undeniably powerful force, the unity of the Irish Volunteer movement found itself shattered by the outbreak of the First World War. John Redmond was determined that the Irish Volunteers should play some role in the war.

At a speech to Volunteers in Woodenbridge, Co. Wicklow Redmond urged the force ‘to go where ever the firing line extends, in defence of right, of freedom and of religion in this war. It would be a disgrace forever to our country otherwise’.

His call for open enlistment to the British army split the Volunteers. The vast majority of its members, some 158,000, endorsed his position and renamed themselves the National Volunteers. 12,000 split and became bitterly opposed. Under Eoin MacNeill’s leadership they retained the name the ‘Irish Volunteers’ and set up their own general council.

In 1914 the Irish Volunteers split into a pro-Redmond, pro-war faction and an anti-war faction led by Eoin MacNeill but heavily infiltrated by the IRB

MacNeill’s split was an empty gesture as he had no real political alternative to the policy of Redmond. It was the IRB who held a substantial and growing influence within the splinter movement which would provide this alternative. That September the IRB appointed a military council to secure effective control over MacNeill’s organisation in order to plan an insurrection. The continuation of the war offered them the opportunity, and more importantly, the time to execute it.

Across Ireland local Volunteer companies held meetings in response to Redmond’s speech in order to declare whether they were for or against him.By December, the RIC calculated that nationally 93% of the original Volunteers had stuck by Redmond. Members of the GAA within the movement appear to have followed suit. When the split came it was the constitutional Volunteers under Redmond that received the majority of support from within the national membership of the GAA.

There is some evidence that the wider split in the Volunteers permeated into individual clubs. In the autumn of 1914 the Laune Rangers club in Killorglin, south Kerry, almost fragmented in two over reports of a dispute among its members due to the Volunteer split.Despite the dominance of the IRB in the GAA’s Central Council and their close connections with the MacNeil’s more radical splinter group, they had little influence over the loyalty of the Association’s grassroots membership.

The GAA Central Council took the wise course of neutrality as far as the split was concerned

The Central Council instead took the wise course of neutrality as far as the split was concerned, fearful that any open alignment with either section would cause an unhealable rift among officials and rank and file members. When an extraordinary meeting of the Central Council was called in December to consider the Kerry motion to form rifle clubs in the GAA, the Kerry delegates were persuaded to withdraw the motion after concerns were raised by their Cork counterparts that it would lead to a political divide within the membership of the Association.

The following April at the GAA’s Annual Congress in Dublin, proceedings started at an early hour so those members who supported Redmond’s National Volunteers could attend an Easter parade rally of the force that afternoon. However, despite such deference for the sake of keeping the organisation intact, unofficially the GAA’s Central Council sided with the IRB-dominated faction.

Regardless of the superficially neutral stance taken by the Central Council, the Kerry County Board seems to have also clearly aligned with the Irish Volunteers. Indeed, a substantial group of GAA officials in Kerry such as Austin Stack, Tadgh Kennedy and Diarmuid Crean were members of the county’s IRB network. Stack himself was the acknowledged head of the IRB organisation in Kerry.

The Irish Volunteers there, no doubt as a consequence of the heavy GAA involvement, were organised using the same model. Just as each GAA club in the county sent delegates to the annual Kerry GAA Convention, so each Volunteer company in the county was represented, often by the same delegates, at an Annual Convention of Kerry Irish Volunteers. The first such Volunteer Convention was held in November 1914 at which a Volunteer County Board was elected along GAA lines.

Support for the Irish Volunteers remained strong among the membership of the Kerry GAA. When Kerry played Louth in a challenge match in Dundalk on Easter Sunday 1915 the large crowd called for cheers for the famous Kerry team. However, Dick Fitzgerald, captaining the side, cried out for three cheers for Eoin MacNeil and the Irish Volunteers instead. In May 1915 Kerry played an inter-county challenge match against Dublin in Killarney. Afterwards a parade of Kerry Irish Volunteers took place on the sports field and was reviewed personally by Eoin MacNeil.

The split in the Volunteers and the energy increasingly devoted to drilling and military activity by the more radical splinter group had a detrimental effect on the management of the GAA in many areas. In 1915, the newspaper Sport reported that the GAA in Derry had fallen away ‘to nothingness’ owing to Irish Volunteer activity.A similar situation had developed in Tyrone where the recently revived GAA virtually collapsed owing to large scale Volunteer recruitment. Likewise in Kerry,involvement in the Volunteers significantly curtailed the operation of the Association there. By early summer, the Kerryman was complaining that meetings of the Kerry County Board were failing through due to lack of sufficient members present to form a quorum.

The GAA and the approaching storm

As 1916 approached, the IRB began to exert increasing control over the Irish Volunteers. Due to the crossover in membership between leading GAA and Volunteer officials, Kerry represented a county where the IRB could reasonably expect the co-operation of the local GAA leadership for its plans to land German arms to support a planned insurrection. In October 1915, Padraig Pearse visited Tralee and informed Austin Stack of the Military Council’s plans to stage a revolt in Ireland against British rule using the Irish Volunteers.

The IRB expected the co-operation of the Kerry GAA leadership for its plans to land German arms to support a planned insurrection in 1916. Over 300 GAA members fought in the Rising of that year.

In preparation for this Stack used the All-Ireland Final between Kerry and Wexford in November 1915, as cover for an operation to smuggle a sizeable consignment of weapons from Dublin in order to properly arm the local Volunteers so as to protect the planned German arms landing. Tadgh Kennedy was put in charge of a group of Volunteers ostensibly travellingas supporters to the match. The morning after the game, Kennedy’s men secured the weapons consignment and it was smuggled aboard the returning supporters’ train to Tralee that Monday evening.

The Rising itself would demonstrate the extent of the interaction between radical Volunteerism and GAA membership. Though it is clear the Association as a body was no active participant in the rebellion nor had its national leadership possessed any inside knowledge on the secret planning of the Rising, this is not to imply that there were not a noteworthy amount of politically active members within the GAA who fought that Easter.

In Dublin, a total of 302 players from fifty-three clubs numbered among the rebels. Five of the fifteen men executed for their part in the Rising had GAA connections. Other prominent rebels captured, such as Austin Stack, Harry Boland, Michael Collins, J.J. Walsh and Thomas Ashe, had been prominent local and national administrators within the organisation. Though these figures demonstrate that GAA members were still very much a minority among the rebels of 1916, they nevertheless indicate a significant role the GAA played within the Volunteer movement both locally and nationally.

Further Reading

Bureau of Military History Interviews, http://www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie/bmhsearch/browse.jsp

Gaelic Athlete

Tom Garvin, Nationalist Revolutionaries in Ireland, 1858-1928 (Oxford, 1987).

Richard McElligott, Forging a Kingdom, The GAA in Kerry 1884-1934 (Cork, 2013).

William Murphy, ‘The G.A.A. During the Irish Revolution, 1913-23’, in M. Cronin, W. Murphy and P. Rouse (eds.), The Gaelic Athletic Association, 1884 – 2009 (Dublin, 2009).

National Library of Ireland, Colonel Maurice Moore Papers, Account of the Irish Volunteers in 1914, MS 8489.

National Library of Ireland, J.J. O’Connell Papers, Autobiographical Account of Events Leading to 1916, MS 22, 114.

National Volunteer

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Dr Richard McElligott lectures in modern Irish history in UCD and he is also chairman of the Sports History Ireland society. His first book, Forging a Kingdom, The GAA in Kerry, 1884-1934 was published recently by the Collins Press.

He is delivering a talk on the GAA in the 1890s on May 28, 2014 at 7 o’clock in the National Library of Ireland.