Today in Irish History – July 10 1921 – Belfast’s Bloody Sunday

In Irish history, “Bloody Sunday” generally refers to events in Dublin in November 1920 or Derry in January 1972. But there were in fact Four ‘Bloody Sundays’ in 20th century Ireland. One of them took place in Belfast in 1921. Here, Kieran Glennon, author of “From Pogrom to Civil War – Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA”, describes what happened.

On Sunday, 10th July 1921, west Belfast erupted. Bullets raked the city’s trams. Rival nationalist and loyalist snipers traded shots from rooftops. Mobs burned rows of houses, especially along the unofficial frontier between catholic and protestant neighbourhoods.

Belfast had always been volatile in July – owing to the parades of the Orange Order on 12th July – but this was violence intensified and militarised on a scale not seen before. Why, on the day before the Truce that formally ended the Irish War of Independence, did the city see one of the bloodiest days in its history?

Answering this question requires taking a look at the preceding year of violence in the city.

Background – the “Belfast pogrom”

The War of Independence came late to Belfast, but when it did arrive in mid-1920, it did so amid bitter sectarian violence.

On the morning of 21st July 1920, loyalist mobs expelled thousands of catholics, as well as protestant trade unionists, from their workplaces in the Belfast shipyards and elsewhere in the city. Sectarian rioting ensued that evening, with the British Army called into action to separate the rival factions.

This marked the start of what became known as the “Belfast pogrom”. The situation was exacerbated the following month, when the IRA killed an RIC District Inspector in Lisburn; by the end of August, almost fifty people had been killed in communal violence in Belfast.

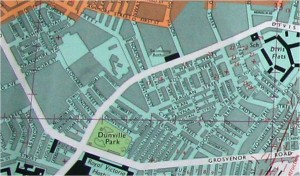

A siege mentality among the nationalists of the Lower Falls and Clonard districts of west Belfast was almost inevitable. They were tightly policed, ringed by four RIC barracks at Springfield Road, Cullingtree Road, Divis Street and College Square.

Severe sectarian rioting broke out in Belfast in mid 1920.

Unlike elsewhere in Ireland, the nationalist community from which the Belfast IRA was drawn was in a small minority among its unionist neighbours, so the IRA was soon pressed into service to defend nationalist areas from attack by both the police and loyalists.

One of its commanders, Roger McCorley, explained that they favoured, “an elastic system of defence” of Catholic neighbourhoods. There was “a central position in each area [with] a picket armed with rifles.” These men were alerted by signallers equipped with flashlights with different coloured bulbs, who could warn of incursions by hostile forces, allowing the picket to be rushed to defend the area if needed. A red flash meant imminent danger.1

In the autumn, the Belfast IRA, severely short of weapons, adopted the same tactics used by their southern colleagues to acquire arms – seizing the guns of RIC men on patrol. The first such incident on 25th September led to the death of a policeman, Constable Thomas Leonard.

That night, a group of Leonard’s colleagues, based in Springfield Road barracks and under the leadership of District Inspector John Nixon, broke into the homes of three republicans in the Clonard area, killing them.

Similar reprisal killings followed IRA attacks on the RIC and Auxiliaries in Belfast during the spring and early summer of 1921 – in each case the homes of nationalists were broken into by the police and they were either killed on the spot or abducted to be killed elsewhere. Nixon and his group of rogue RIC men soon became known to nationalists as the “murder gang.”

A more official response to the ongoing campaign of the IRA came in October 1920, with the formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary. This new force was organised into three classes: A Specials were full-time and paid and worked alongside the regular RIC; B Specials were part-time and unpaid, but had a separate command structure to that of the RIC, which meant that they operated according to their own orders; finally, C Specials were part-time, unpaid and non-uniformed – they were usually more elderly and generally used for guard duties on public buildings.

The Raglan Street ambush

On Saturday 9th July 1921, following negotiations between the British and Sinn Féin, a Truce was announced which would come into effect throughout Ireland at midday on Monday 11th.

Both sides were to halt all offensive operations and police raids were also to end. The timing, coming just before the annual “Twelfth” commemorations in the north, could not have been worse – to loyalists, it seemed that the IRA was reaping benefits from its violence of the previous eighteen months.

According to Sean Montgomery, a member of the IRA, the police decided to mount one last raid on the night the Truce was announced:

“…Tommy Flynn and I were told to report to Brigade I.O. The late Frank Crummy [sic], school master, who lived next door to the school in Raglan Street, told us that the Parish Priest of St. Paul’s had the new D.I. of Springfield Barracks in with him and that if anything happened that night it wasn’t his fault as he was not in charge. D.I. Nixon was taking over for a short time, so when Nixon was there we could guess what for’. 2

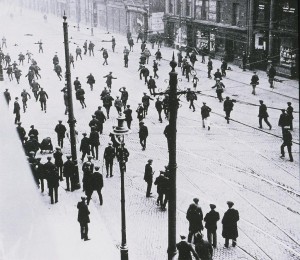

July was a tense time in Belfast with the Twelfth looming and rumours of a truce between the IRA and the British.

The targets of this raid would appear to have been either Frank Crumney, Intelligence Officer of the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division, who lived at 59 Raglan Street, or Tommy Flynn himself, Captain of D Company, 1st Battalion, who lived at number 3 in the same street. The police may equally have been seeking both.

Forearmed with the priest’s warning, and fearing that Nixon’s involvement pointed to a “murder gang” attack, a defensive picket of fourteen men was put on standby, of which Montgomery was one:

“We were on alert about 11:20p.m. when we heard the alarm from the Loney – bins, whistles, etc. Down we moved, seven men on each side of the street. When we got as far as Nail Street we met the O.C. of the district. He told us it was a false alarm so back we went to Raglan Street.” 3

But the danger was real. Montgomery recalled:

“When we entered Raglan Street a lamp was flashing red [the signal of a hostile incursion] so we moved up to Peel Street. Captain Flynn gave orders that no man was to fire until he gave the order. Then J. Burns one of the scouts came running, he told us they were drunk with their faces blackened – that was a murder gang. The tender came slowly, when it got about 10 feet from Peel Street [the] Captain opened fire.” 4

Montgomery described some wild firing by the IRA:

“I was about 15 or 16 feet off it when 14 guns roared. A second volley was fired into it. The Captain got round behind. I and three men made the move through one house, over the wall and into the next street and came up to the tender. The men were still firing when we came to the corner. Jack Donaghy shouted for us to look out as our own bullets were hitting where we were.” 5

But it was one man armed with a handgun who did the most damage:

“We turned a corner then a shout in a Southern Brogue, ‘Halt, hands up!’ Jack Donaghy was using a Peter Painter 12 rounder [Mauser C96 automatic pistol]. He opened fire, three Policemen fell, one killed and two wounded.” 6

An IRA ambush of an RIC incursion into Raglan Street left a policeman dead and two wounded

The dead policeman was Constable Thomas Conlon, based in Springfield Road barracks; the two wounded were Constable Edward Hogan and the driver of the Crossley tender, Special Constable Charles Dunne. Conlon, a catholic policeman originally from Roscommon, was viewed by the IRA as being sympathetic – according to Montgomery, “he was good at giving tips of police raids.”

The most immediate response to the ambush was that a GAA club hall was burned down in Raglan Street that night, where it was stated that “a German rifle and a thousand rounds of ammunition” were found by police during a follow-up search. As no loyalists could have penetrated so deep into the Lower Falls, the hall must have been burned by the police. This was merely a foretaste of what was to come.

Bloody Sunday

The next day saw a ferocious reaction to the ambush. The nationalist Irish News reported that, owing to concerted attack by both loyalist and the police;

The next day saw a ferocious reaction to the ambush. The nationalist Irish News reported that, owing to concerted attack by both loyalist and the police;

“The entire Nationalist district from Grosvenor Road on the one side right up to the borders of the Unionist quarter on the Shankill Road was practically in a state of siege from the early morning until late in the evening … While the trouble was in progress in these areas the sound of rifle and revolver shots rang out almost continuously … armoured lorries patrolled the streets, firing indiscriminately as they went.” 7

Passengers in trams travelling along the Falls Road into town had to take cover from the gunfire by lying on the floor; the trams were diverted, first down the Grosvenor Road, but eventually, as the violence spread, down the Donegall Road. As if the situation was not already tense enough, “It was rendered infinitely worse by the actions of the Crown forces in careering along the streets, firing in all directions.” 8

Sixteen people were killed on what became known as “Bloody Sunday” – apart from Constable Conlon, ten of the dead were catholic and five protestant.

Sixteen people were killed on what became known as “Bloody Sunday” – apart from Constable Conlon, ten of the dead were catholic and five protestant.

One of the first fatalities was Alexander Hamilton, who “…merely glanced round the corner of Conway Street when a Unionist sniper at the Shankill end of that thoroughfare sent a bullet through his head.” 9

One woman witnessed the death of her husband, an ex-serviceman named Daniel Hughes of Durham Street:

“…he was walking along Pound Street, which leads from Durham Street to Divis Street, looking for his three boys, who happened to be out. She was standing at her own door at the time and when her husband was in the act of going round the corner of the street she declares that she saw members of the Crown forces fire point blank at him and almost blow his head off. She said to the man who fired the fatal shot ‘You have killed my husband!’ but he would not look her in the eye.” 10

Amid the mayhem, even children were deliberately targeted: twelve-year-old William Baxter was killed by a nationalist sniper that afternoon as he went to Sunday School in Ashmore Street; the same sniper may also have been responsible for the death of sixteen-year-old Ernest Park, who was also shot in Ashmore Street, as he carried a kitten to a friend’s house.

While the nationalist press attributed the entire blame for the violence to the police and loyalists, the unionist papers exclusively blamed “Sinn Fein snipers” and were more supportive of the authorities, stating that “…the police were very plucky in returning the attacks in the disturbed districts, having regard to the advantage the disturbers possessed in being quickly able to conceal themselves.” 11

There was no attempt to claim that Bernard Monaghan was a concealed sniper: he was aged seventy when killed on his doorstep in Dunville Street. William Tierney was killed while sitting in his own kitchen in Osman Street, a location that made it impossible for the fatal shot to have been fired by anyone other than a passing police patrol.

As well as those killed, scores of people were wounded – over forty were brought into the Royal Victoria Hospital on the Falls Road and more than sixty others were admitted to the Mater Hospital in the north of the city; one of these finally succumbed to his wounds the following April, bringing the final death toll for Bloody Sunday to seventeen.

In Belfast’s Unholy War, author Alan Parkinson makes an interesting observation that four of the nationalist fatalities were ex-servicemen. 12 In its reporting of the events, the Irish News stressed that ex-servicemen living in Cupar Street, which ran between the Falls and Shankill districts, had also made up a disproportionate number of the victims of another facet of the violence – the destruction of houses:

“A pub was looted and burned, after which the mob, made up of men and women, saturated with drink, completed their job by setting fire simultaneously to twenty houses of Catholics.” 13

Altogether, a hundred and sixty one houses were burned that day, twenty-eight of them in Cupar Street alone.

Defence of nationalists

The IRA found itself stretched to the limit in trying to repel the attacks. According to Roger McCorley:

“There was very heavy fighting all over the city, even the city centre itself was swept by rifle and machine gun fire. Every weapon which we had in our possession was in action that day. The British, especially the Special Constabulary, seemed to be completely out of hand and were bent on massacre. Armoured cars passed all through our areas and kept up a continuous fire into the houses. Anything moving, man, woman or child, was fired on. A heavy concentration of snipers kept up a continuous fire into the nationalist areas.” 14

Both the IRA and other national groups attempted to defend catholic neighbourhoods.

One curious incident suggests that the IRA may not have been alone in defending nationalists: an off-duty policeman in plain clothes was relieved of his revolver by a picket of men in Pound Street in the Lower Falls but when it was later discovered that the gun was a police weapon, it was returned to the RIC barracks on Cullingtree Road.

Given that the IRA had previously shown no compunction in killing RIC officers to get their weapons, it seems highly unlikely that they were responsible in this case – which implies that other nationalists had also organised a defence of the area.

The most likely candidates in such a case would have been the Ancient Order of Hibernians, a sectarian secret society led by the Nationalist MP for Belfast Falls, Joe Devlin. If the story had been reported by the Irish News, it might justifiably be viewed as stretching the boundaries of nationalist innocence beyond credibility, but it was actually reported by the unionist Belfast Telegraph. 15

Joe Devlin was quick to raise protests over the violence at Westminster the next day, pointing out that “…in not a single instance had anything been done to protect these innocent victims from miscreants in uniform.” 16

The authorities’ response

The terms of the Truce throughout Ireland (which came into force on July 11th) created hesitation among the authorities about how to respond to the rioting that had erupted. A measure of their confusion can be seen from two proclamations that appeared in the press, both issued by Colonel Commandant Carter-Campbell, the commanding officer of the British Army’s 15th Infantry Brigade.

Assistant Under-Secretary for Ireland Alfred Cope was adamant that sending the Specials into the disturbed areas “would be the equivalent of pouring petrol on the fire.”

The first, dated 9th July (the day on which the Truce was originally agreed), rescinded the curfews then in place for Belfast, Derry and Newry; the second, immediately below it and dated 11th July, reinstated the curfew for Belfast. 17

Assistant Under-Secretary for Ireland Alfred Cope was adamant that sending the Specials into the disturbed areas “would be the equivalent of pouring petrol on the fire.” 18

Evidently, Chief Secretary Hamar Greenwood took heed of both Cope’s advice and Devlin’s protests, for he announced that “…it had been decided to remove armed semi-civilians known as ‘B’ Specials from the streets altogether and to disarm the ‘A’ Specials who wear uniforms and are paid as policemen.” 19

Since the initial outbreak of the pogrom the previous year, it had largely been the role of the British Army to quell outbreaks of violence – given the deep-seated hostility between the RIC and Specials on the one hand, and both armed and unarmed nationalists on the other, only the military could be relied on to act impartially.

However, the Truce specified that neither side was to put armed men on the streets and Dawson Bates, Northern Ireland Minister for Home Affairs, told Prime Minister James Craig: “At the same time, my instructions to Col. Commandant 15th Brigade are that…troops will be guided by the spirit of the agreement entered for the cessation of hostilities.” 20

Confused, Carter-Campbell did not order his troops to leave their barracks and impose order on the streets as they would normally have done. This left the security response in the hands of the RIC.

The police returned to their barracks late on the night of Sunday 10th / Monday 11th, after a ceasefire had been agreed by phone between a senior RIC officer and the O/C of the IRA’s Belfast Brigade, Roger McCorley. However, McCorley later observed “The pogrom lasted 2 years…the Truce itself lasted six hours only.” 21

The following days

The Truce was due to begin from midday on Monday 11th July, but rioting resumed that morning:

“… huge crowds of Unionists surged in by back ways from the Shankill Road district and proceeded to attack the streets … They rushed up the streets yelling and cursing and using the most violent threats … Men armed with sledges and other heavy weapons went ahead of the main body and smashed in the doors and windows, while others of them went into the houses and threw or carried out everything that was portable. Groups of women seized upon the articles and carried them away.” 22

The mother of thirteen-year-old Mary McGowan saw her daughter shot dead from a police armoured car in Derby Street off Divis Street – she was wounded by the same burst of gunfire that killed her girl. Two adults also died that day – one of them was an IRA Volunteer, Seamus Ledlie, who was shot by a sniper in Norfolk Street just ten minutes before the Truce officially came into effect. 23

By the end of the week, twenty-three people had been killed in Belfast, hundreds more wounded, two hundred homes destroyed and a thousand people made homeless.

At the same time as they were trying to protect against the attacks of the police and loyalists, the IRA were also faced with an additional challenge from within the nationalist community in the form of the Devlinite Ancient Order of Hibernians. Joe McKelvey, O/C of the 3rd Northern Division, reported to GHQ in Dublin that:

“The rioting had practically ceased by noon on Monday when a new difficulty arose. The Catholic mob, infuriated by the burnings of their homes, set fire to a large establishment in the Catholic area owned by Wordie & co., carting agents, and before we became aware of what was happening the fire had taken a hold on the building.

One of our men, who happened to be passing at the time, was actually beaten by the mob for his attempting to frustrate their design. On receipt of the information a party was immediately despatched to the scene and it was only with great difficulty they succeeded in preventing the mob from cutting the hose pipes of the Fire Brigade in its attempt to extinguish the flames.

The Belfast Brigade Commandant informs me that he is experiencing great difficulty in maintaining order as the Catholic mob is beyond control.” 24

However, McCorley made no bones about how the IRA dealt with the issue:

“That same evening [11th July] a most unexpected state of affairs came about. An element of the Nationalists, under the control of the Hibernians, started to loot the unionist business premises in the Falls Road area…It was obvious that this was due to pique at the fact that our people were now accepted by the British as the official representatives of the Irish people.

On several occasions during the day our men had to turn out and fire on this mob. They fired over their heads but later on in the evening I gave instructions that if the mob gave any further trouble they were to fire into it. We also sent our patrols with orders to arrest the ring-leaders of this group and bring them to Brigade headquarters. This was done and we ordered several of the ring-leaders to leave the city within twenty-four hours, otherwise they would be shot at sight. This action ended the Hibernian attempt to break the Truce.” 25

Tuesday saw the annual “Twelfth” Orange parades pass off peacefully and there were no serious disturbances in the city.

On Wednesday 13th, one woman was killed in the Lower Falls and rioting spread to York Street in the north of the city and Ballymacarrett (Short Strand) in the east, but it was less intense than on previous days.

In west Belfast, that day was most notable for the series of funerals for the victims of Sunday’s violence, which were followed by hundreds of mourners along the Falls Road to Milltown Cemetery; Seamus Ledlie (the IRA man killed in Norfolk Street) was given a full paramilitary funeral, with a tricolour draped over his coffin, a pipe band leading the cortege and what the Irish News described as “Irish Volunteers marching four abreast” following behind. 26

By the end of the week, twenty-three people had been killed in Belfast, hundreds more wounded, two hundred homes destroyed and a thousand people made homeless. 27

The city experienced a month of relative calm thereafter, with only one death before – almost inevitably – widespread violence broke out again in late August.

Aftermath

Raglan Street no longer exists – the Lower Falls was redeveloped during the Troubles and as well as the old, two-up-two-down, redbrick terraced houses being modernised, the layout of the area was substantially changed, with many of the old streets being built over. Raglan Street was one of them but the ambush that took place there had already long since become the subject of a song:

Oh I’ll tell you a tale of a row in the town

When a lorry went up and it never came down

It was the neatest oul’ sweetest row you’d ever meet

When the boys caught the Specials down Raglan Street 28

However, the lyrics merely illustrate the ability of some republicans to turn calamities into ballads, as the events surrounding the ambush were by no means a triumph for the IRA. While successful in thwarting an attempt to capture or kill two of their senior officers, the killing of a policeman subsequently cost them the life of one of their volunteers.

The nationalist population of west Belfast, who the IRA was supposed to defend, paid a terrible price for the ambush.

More importantly, the nationalist population of west Belfast, who the IRA was supposed to defend, paid a terrible price for the ambush. Over the entire twenty-seven months of the pogrom, a total of thirty-five catholic civilians died in the Lower Falls and Clonard areas; a quarter of all these deaths occurred in just four days – Bloody Sunday and the three days afterwards.

I have argued elsewhere that in west Belfast between July 1920 and October 1922, for the most part “…a combination of the military, IRA and other nationalists were at least able to keep the loyalists at bay to some extent.” 29 However, the confinement of the British army to barracks, in order to avoid breaching the Truce, meant that the main burden of defending nationalist areas in mid-July 1921 fell on the IRA. Events that week proved that, unaided by the military, they were not equal to the task.

While the IRA may be deemed culpable for failing to prevent the reprisals that followed the Raglan Street ambush, the primary responsibility for the savagery that ensued lay with the police – in particular, with the Specials.

This was borne out at the inquest into the death of young Mary McGowan, shot in Derby Street on Monday 11th. At the time, Belfast inquest juries tended to be broadly sympathetic to the authorities – “Dr. Graham (coroner) said the police had been doing their duty very well” was a typical observation. 30

However, in this case, the jury made a remarkable change to its own verdict. It heard from an eyewitness that the Special Constabulary “…engaged in wild and indiscriminate firing. He went on to say that there was no need for the firing and added that everything was quiet until the police arrived.” 31

The jury found that the girl was shot by Crown forces. District Inspector Duignan asked that the particular section should be specified, so the jury then altered the words “Crown forces” to “Special Constabulary”. D.I. Duignan disputed the finding and asked for an adjournment of a week so that members of the Special Constabulary could testify. 32

A week later, the re-convened inquest heard a denial of police responsibility from RIC Head Constable Pakenham, who had been in command of the armoured car in question (and who was named as a suspected member of the Nixon “murder gang” in an IRA intelligence document 33).

But not alone did the jury re-iterate its finding of the previous week – namely, that the Specials had deliberately killed the girl – but it also added a most unusual rider to the verdict: “In the interests of peace, Special Constabulary should not be allowed into localities of people of opposite denominations.” 34

The violence that erupted around the time of the Truce was the most vicious that Belfast had seen since the initial outbreak of the pogrom – July 1921 saw the highest number of killings in a single month since the twenty-seven deaths of the previous August. However, that figure would soon be surpassed the following November – and even worse horrors lay ahead in 1922.

Notes

- Roger McCorley statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS0389

- Sean Montgomery statement, O’Mahony papers, National Library of Ireland, Ms 44,061/6

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Irish News, 11th July 1921

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Irish News, 13th July 1921

- Northern Whig, 11th July 1921

- Alan Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2004), p154

- Irish News, 11th July 1921

- Roger McCorley statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS0389

- Belfast Telegraph, 13th July 1921

- Irish News, 12th July 1921

- Northern Whig, 12th July 1921

- Quoted in Patrick Buckland, The Factory of Grievances: Devolved Government in Northern Ireland 1921 – 1939 (Dublin, Gill & McMillan, 1979), p189

- Irish News, 12th July 1921

- Buckland, The Factory of Grievances, p186

- Roger McCorley statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS0389

- Irish News, 12th July 1921

- Roger McCorley statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS0389

- Operations Report, 3rd Northern Division, 12th July 1921, Mulcahy papers, UCD Archives Dept., P7/A/22

- Roger McCorley statement, BMH, Military Archives, WS0389

- Irish News, 14th July 1921

- Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War, p153

- Ibid

- Kieran Glennon, From Pogrom to Civil War – Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA (Cork, Mercier Press, 2013), p271

- Belfast Telegraph, 18th August 1921

- Belfast Telegraph, 11th August 1921

- Ibid

- File on District Inspector John Nixon, Blythe papers, UCD Archives Dept., P24/176

- Belfast Telegraph, 18th August 1921