Commemorating the Easter Rising Part I, 1917-1936

How was the insurrection of 1916 commemorated? The first part of a two part article by John Dorney

The Easter Rising of 1916, perhaps the most dramatic event of modern Irish history was over after just five days of fighting. The shadow cast by the insurrection however, however, lingers until the present.

The Rising launched on April 24th 1916 was the first credible Irish Republican insurrection since 1798. The first since then that could not, like the abortive Young Ireland uprising of 1848 or the Fenian rebellion of 1867, be laughed off by its enemies as a fiasco. The rebel fighters of 1916, were, retrospectively if not at the time, hailed as heroes, its executed leaders venerated as martyrs.

From the example of Easter Week, Irish Republicans could draw inspiration; from the bravery and self-sacrifice of those who took part of course, but also from the fact that the bold example of the Rising had apparently transformed Irish public opinion.

For this to happen though and for the Rising to remain such as potent symbol it had to be commemorated.

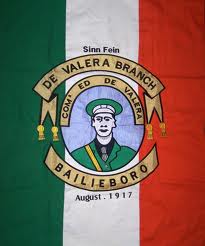

The First anniversary, Easter 1917

The first question was when to commemorate the events of 1916. The Rising had broken out on April 24th and Pearse had surrendered on April 29th of that year. However the Rising had also been deliberately timed to coincide with the Christian festival of Easter, which of course changes dates every year, being tied to the lunar calendar.

In 1917, in Lewes prison in England, where some of the Rising’s surviving leaders were still interned, the prisoners chose April 29th, the anniversary of the surrender as their day of memorial.

Paul Galligan who had led the rebellion in County Wexford wrote to his brother that on April 29th, they held a memorial service for the Volunteers who had died in Easter week, “those noble souls, the purest and best of Irish manhood and although we feel lonely and sad for such comrades yet we cannot regret them, they have led a noble life and died a glorious death”.[1] The prisoners also organised Irish language and Irish history classes.

In Dublin though, activists chose instead Easter Sunday which fell on April 9th that year. According to Helena Moloney;

‘We decided to have a demonstration to commemorate the rebellion – “The Republic still lives. A Republic has been declared, has been fought for; and is still alive”. We had a lot of discussions. There were concerts arranged, but what I was concerned with most was our decision to be-flag all the positions that had been occupied in the 1916 Rising. We intended to run up the flags again in all these positions and to get out the proclamation, and proclaim it again, and to try to establish the position that the fight was not over and that the Republic still lives.’[1]

The first question for commemoration was whether to go for the date of the Rising -April 24th to 29th or Easter Sunday.

And so, almost a year on from the Rising, on April 9th 1917, Dublin commemorated the insurrection with a riot. A republican tricolour was hoisted over the ruined GPO and another over Nelson’s pillar, the spiralling monument that overlooked it. ‘That was the signal’, the Irish Times reported, ‘for an outburst of cheering and various other demonstrations of approval on a wide scale’.

When the police, after some effort, sawed down the temporary flagpole, they were stoned by inner-city youths, who used as missiles the debris of the building work that was re-building O’Connell Street. The police had temporarily to retire from the north inner city as what the Irish Times sniffily called ‘young toughs’, looted shops, damaged a Methodist Church and overturned several trams.[2]

Elsewhere in the country too, the first Easter Sunday after the Rising was the occasion for display of defiance by local separatists.

Jerome Buckley of Mourne Abbey, County Cork, recalled that the Rising’s first anniversary was the first ‘happening’ in his area, in which he and other local youths flew tricolour flags from, ‘from two of the highest points in the district … a high tree in Analeentha, [and] Mourneabbey Castle.[3]

Similarly, Henry O’Keefe in Waterford said that, ‘Our first hint of defiance occurred at Easter, 1917, when we placed the Tricolour on tops of trees, chimneys of houses, and telegraph poles to celebrate the anniversary of the 1916 Rising.’ [4]

The first anniversary in 1917 was an opportunity for separatists to show their renewed defiance to Britain.

The flying of the illegal republican tricolour seems to have taken place in many locations around the country, forcing the RIC to try to take them down, as O’Keefe remembered ‘with difficulty in many places’. Joe Lawless in Fingal, North County Dublin had a run in with ‘Sergeant O’Reilly of Swords’ who arrived on a bicycle to complain about the tricolour flying on Lawless’s lawn.

‘He told me that the presence of this flag had been reported to the authorities and that he had been ordered to remove it. Anticipating my refusal to allow its removal, he went on to say that his mission had nothing to do with his personal feelings in the matter. ‘[5]

The first Easter Sunday after the Rising began a Republican tradition of commemoration on that day.

However it seems that in the years that followed, first with public assemblies forbidden under the Defence of the Realm Act and then in the escalating violence of the War of Independence, it was too dangerous to have large, public parades in remembrance of the Rising.

The first year where Republicans were again able to parade openly in the streets was the Easter Sunday of 1922, which fell on April 23rd. By this time the political context was very different from 1916 or 17. Now after the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the British were leaving what was now the Irish Free State’s capital but the IRA had split. Only ten days earlier an IRA force opposed to the Treaty had occupied the Four Courts in central Dublin in defiance of the Provisional Irish government. Civil War was in the air.

The Easter commemorations seem to have involved only the anti-Treaty faction and in contrast to more long established events such as the Wolfe Tone commemoration at Bodenstown, seem to have been fairly low key.

The Irish Times reported on a ‘Procession to Glasnevin Cemetery’, which started from Church Street and featured a ‘Large body of men and women wearing the uniform of Cumman na mBan, headed by St James Band, Irish Citizens Army pipers and the St Laurence O’Toole band.’ They wound their way from Church Street over to Westmoreland Street and then through the north city centre to Glasnevin, where they, ‘ Played the Soldiers Song’ (now better known by its Irish title Amhran na bhFiann’), and then returned to the city.

Post Civil War Commemorations

The Civil War of 1922-23 to paraphrase Yeats, ‘changed utterly’ the context in which the Rising of 1916 would be seen and commemorated.

The Republicans of 1917-21 saw the 1916 insurrection as being vindicated by the subsequent swing in public opinion behind the separatists of Sinn Fein in the election of 1918. The Irish Republic declared at the GPO could, retrospectively be seen having as been democratically endorsed.

The Civil War changed all this. The pro-Treatyites, many of them – such as W.T. Cosgrave, Richard Mulcahy, Desmond Fitzgerald and others, veterans of the Rising – now claimed that they had upheld ‘the will of the people’ against the unrepresentative extremists in the ranks of the ‘Irregulars’ or anti-Treatyites. As a result, 1916 and all it stood for, in terms of celebrating armed action by a radical minority, was suddenly a rather uncomfortable legacy to celebrate.

The Civil War of 1922-23 changed utterly the context in which the Rising of 1916 would be seen and commemorated

Thus the early Free State commemorations tended to be quite low key affairs.

In 1924, just after the Civil War, they held a ceremony at Arbour Hill on the eighth anniversary of executions of Pearse, Connolly, Clarke and the other leaders at Arbour Hill. Mass was said by a Reverend Piggot to a congregation that included the Free State Cabinet and the National Army command. A party of National Army troops marched to graveside, fired volleys and played last post. And that was all.[6]

This set the tone for the rather restrained Free State commemorations of the Rising. In fact the pro-Treatyites mounted much larger military displays outside the Dail every August 11th, the anniversary of Arthur Griffith’s death, in honour of him and pro-Treaty martyr Michael Collins.[7]

So the anti-Treaty Civil War faction, or Republicans as they termed themselves, were able to make the Easter Commemorations their own to a large degree. They could argue that, like the rebels of 1916, they were a minority, but that they alone stood for the full independence of all of Ireland.

In April 1925, by which time the last Civil War prisoners had finally been released, the Republicans mounted demonstrations all over the country in ceremonies that combined remembrance of the Rising and commemoration of the death of anti-Treaty IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch in April 1923.

Eamon De Valera addressed about 4,000 followers at the Liam Lynch memorial in the Galtee Mountains and told them that the ‘Republic cannot be achieved by force of arms’. But Lynch, like the dead of Easter Week ‘Had not died in vain’. ‘We will not be slaves’.

In Dublin there was again a Republican procession to Glasnevin to mark the 9th anniversary of 1916. The Irish Times reported that ‘Forces of military and police were on duty to preserve order.’ No volleys were fired over the graves of the Republican dead. There was also a procession in Nenagh of over 2,000 people ‘for all the North Tipperary Volunteers who had died since 1916’. In Dundalk meanwhile, a march was told by Frank Aiken that they ‘would never recognise a six county nor a 26 county state’.

The following year, the tenth anniversary of 1916, was similar story. The official Free State commemorations were confined to the Catholic Mass and military ceremony at Arbour Hill, whereas the Republican opposition, coordinated by the ‘Easter Week Commemoration Committee’ held marches across the country.

There was the now annual march to Glasnevin which now featured Republican TDS Eamon de Valera, Sean Lemass, Tom Derrig, Mary MacSwiney, music by Eamon Kent Band and Workers’ Union Band. Also present were Cumann na mBan and the Fianna led by Constance Markiewicz, along with James Larkin’s Workers Union of Ireland with a flag ‘Remember Black ‘47’ and ‘section of unemployed’, Grocers Association and ‘Republican Volunteers’.

Though many pro-Treatyites were also veterans of the Rising it was the anti-Treaty Republicans who made the Easter commemorations their own.

At the cemetery they were addressed by Eamon de Valera himself who said;

‘Ten Years ago the victorious Empire was so sure of itself, that it dared to assume the role of champions of small nations and challenged all who were still in bonds to make manifest their will for freedom. Ireland still had a Clarke, a Pearse and a Connolly, men as courageous as they were wise and the challenge was not allowed to pass. They answered…in deeds. They proclaimed Ireland’s right and Ireland’s will by proclaiming the Republic and they made sure of an Irish Ireland by dying for it.’

‘But our homage and appreciation is not enough whilst the task to which they devoted themselves remains unfinished. The Ireland they set out to deliver is still unfree. … thousands still mourn. We pledge ourselves to the watching spirits of those who lie buried here that they shall not have given their lives in vain.’ [8]

Parades were also held in Cork, Nenagh and Tipperary town.

At this point therefore, the Easter Rising commemorations acquired a somewhat subversive character. Yes, the Irish state traced its lineage back to the Proclamation of the Republic in 1916, but it was vulnerable from the start to the charge that it had betrayed the memory of the Easter rebels with its faint hearted compromises (or at least so they could be portrayed) on the unity and independence of Ireland.

1932 a new departure

This changed to a large degree with accession to power of de Valera’s Fianna Fail in 1932. Now with the anti-Treatyites of 1922 in power, there was much more unabashed celebration of the Rising by those who ran the Irish state.

Frances Flanagan notes, ‘In April 1932, posters of the 1916 Proclamation were plastered over Dublin and official military commemorations were instigated in Dublin and Cork’.

The new government also re-opened Kilmainham Gaol, where the 1916 executions had taken place, as a memorial and commissioned bronze cast of the mythical hero Cuchullain, which still sits in the 1916 rebel headquarters of the GPO. W.T. Cosgrave, the leader of pro-Treaty Cumann na nGaedheal party, refused to attend any of the new functions. [9]

Fianna Fail still retained something of the rebel sprit though. In 1934 ‘Irish Republican Army Parades’ in Dublin assembled at Parnell Square, led by Oscar Traynor and Seamus Robinson and marched to Arbour Hill where they were addressed by Eamon de Valera. The parade paused at the GPO (rebel headquarters in 1916), for a minute’s silence and playing of the last post but then, rather significantly headed down the Dublin quays, and halted again at the Four Courts, for another minute’s silence.

Afte Eamon de Valera’s Fianna Fail came to power in 1932 they tried to integrate the republican commemorations into the official state ones.

The symbolism was obvious, while the Four Courts had been occupied by the insurgents in 1916, it was also where the Civil War had started in 1922 when the Republicans occupying it had been bombarded by pro-Treaty forces. The anti-Treayites of 1922 were now formally claiming the Easter Rising as their own.

Oscar Traynor, one-time head of the IRA Dublin Brigade but now a Fianna Fail TD told the assembled crowd at the graveside at Arbour Hill: It had been ‘Eighteen years since maimed bodies and broken hearts that lay within graves pulsed with hope for the new life they believed their sacrifice would recreate for our tyrant ridden land. ‘

‘It might be asked what did their sacrifice secure for the nation? Did it secure the liberty for which they yearned? Did it make their nation a power among powers?…It did not but it gave a unity of purpose which their long suffering nation had not known for centuries.’

He finished with a ‘Plea for unity’ in ‘Holy cause of free and unfettered Ireland’. ‘Here in close communion with our Holy dead’. ‘We promise that their hope shall be realised and their dreams made into a reality’. … ‘A completely free Ireland such as they visualised’.

However, Fianna Fail were already considered traitors by those who remained with the IRA.

A rival IRA rally at Glasnevin, appealed for recruits into IRA, and Sean Russell told his listeners, a crowd of ‘several thousand people’ that, ‘Constitutionalism has failed in Ireland, so has coercion’, condemning the government’s ‘coercion act’. He condemned ‘national insults’ asking IRA to hand in its weapons and de Valera’s creating of the Volunteer Reserve, an ‘adjunct of Free State army’ to replace the IRA. The IRA was banned by Fianna Fail shortly afterwards, having been legalised in 1932. The Blueshirts, the pro-Treatyite militant group, another possible rival claimant of the 1916 legacy had been banned earlier that year.

By the mid 1930s, rival Republican groups still claimed to be the sole inheritors of 1916.

Interestingly also, that year for the first time, Republicans in Northern Ireland defied the ban there on commemorating the Rising. About 500 people attended a rally at Milltown Cemetery in Belfast, before being dispersed by the Royal Ulster Constabulary. There were also marches at Newry and Derry in spite of the ban. [10]

By 1936, the 20th anniversary of the Rising, the Easter Commemorations had become well established as perhaps the most important event in the Republican commemorative calendar. But by this time they were already a highly contentious and contested series of events. Remembering the Rising of 1916 could be a means of bolstering the southern Irish state, but also ,even after Fianna Fail’s electoral victories, of undermining it too.

There were already those who would never recognise the ‘partitionist’’ Free State and who considered its appropriation of 1916 as a sham. In Northern Ireland, too where commemorating the Rising was illegal, the Easter Commemorations had by 1936, become a means of consolidating and encouraging an anti-state Republican message. The Proclamation of 1916 had declared, ‘The Irish Republic is entitled and hereby claims the allegiance of every Irishman and Irish woman.’ Even twenty years later, the legacy of this sentiment was still bitterly divisive, in Ireland north and south.

References

[1] Paul Galligan to Monsignor Eugene Galligan, 4 May 1917, My thanks to Kevin Galligan for access.

[1] Helena Moloney BMH

[2] Padraig Yeates , A City in Wartime, Dublin 1914-1918, p191-192 , Irish Times, April 10 1917

[3] Jerome Buckley BMH WS 1023

[4] Henry O’Keefe BMH 1123

[5] Joseph Lawless BMH 1023

[6] Irish Times May 9th 1924

[7] Anne Dolan, Commemorating the Irish Civil War, p 17-19.

[8] Irish Times April 5 1926

[9] Frances Flanagan, Remembering the Irish Revolution p36

[10] Irish Times April 2 1934