Airbrushed out of history? Elizabeth O’Farrell and Patrick Pearse’s surrender, 1916.

Michael Barry, author of ‘Courage Boys We are Winning’, a photographic history of the 1916 Rising, examines a famous image to see if women were literally air-brushed out of an iconic moment in Irish history.

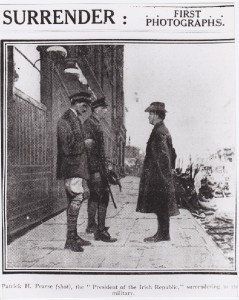

One of the most well-known images from the 1916 Rising is the photograph showing Commandant-General Patrick Pearse facing Brigadier-General William Lowe, in the course of surrender on Saturday, 29th April 1916.

It is iconic, dramatic, well composed and sums up one of the saddest parts of the Rising’s conclusion. Along with the issue of ‘airbrushing’ of Elizabeth O’Farrell, there have arisen, in recent times, many myths and misconceptions about the facts relating to the image and the surrender. In this article I delve into the known accounts and attempt to establish some facts.

The Surrender

On the evening of Friday, 28th April, the republican forces had evacuated the burning GPO. With difficulty they had broken into a terrace along Moore Street, ‘mouseholing’ through walls to occupy the terrace, nos. 10 to 25, on the eastern side of the street. After discussion on options, the leadership of the Provisional Government (located in a back room at No. 16 Moore Street) decided to negotiate with the British.

One of the three women in the group occupying Moore Street was Elizabeth O’Farrell, a member of Cumann na mBan – not a nurse then, but who trained as a midwife after the Rising. She had been caring for James Connolly and other wounded.

She was asked to carry a message to the British. About 12:45 pm on Saturday 29th April, O’Farrell, wearing a Red Cross armband and carrying a white flag, walked towards the British barricade at the top of Moore Street at the intersection with Parnell Street[1]. Her mission was to pass on a message that the Commandant-General of the Irish Republican Army wished to treat with the head of the British forces in Ireland.

After some incredulity on the part of the soldiery, she was detained by the British in Tom Clarke’s shop at the corner of Parnell Street and eastern Upper Sackville Street. Brigadier-General Lowe arrived by car from Trinity College, where he had been directing the suppression of the Rising. He was accompanied by his son, (a lieutenant, only 18 years old) who acted as his ADC and a Staff Captain, the Anglo-Irish Harry de Courcy-Wheeler.

Elizabeth O’Farrell acted as messenger between Republican leader Pearse and British General Lowe during the surrender.

Lowe informed the nurse that Pearse had to surrender unconditionally. She was escorted back to the barricade and then walked to Pearse in Moore Street. She returned from him with a message that specified conditions for surrender. Lowe rejected these; he would only accept unconditional surrender. O’Farrell returned again to Moore Street. In due course, accompanied by O’Farrell, Pearse emerged and they walked back towards the barricade.

O’Farrell, who later was anti-Treaty and hostile to the Free State, did not make a witness statement or apply for a military pension. However her story was told in the 1917 Catholic Bulletin[2]: ‘… General Lowe received Commandant Pearse at the top of Moore Street, in Parnell Street…Commandant Pearse then handed his sword to General Lowe.’

An article in An Fiolar[3], published in 1958, based on information provided by Elizabeth O’Farrell, gives more detail in relation to the photographs. It tells of Lowe’s misconception about the presence of Countess Markievicz, which Pearse proceeds to correct:

‘“I beg your pardon, Mr Pearse, but I know she is in the area.”

“Well she is not with me, sir”, (Pearse answered).

General Lowe wished Nurse O’Farrell to be detained overnight and so bring Pearse’s capitulation order to the leaders of the other garrisons.

“Will you agree to this?” Pearse asked her.

“Yes, if you wish it.”

“I do wish it.”

At this, Pearse in the deepest silence, proffered his sword in surrender to the General. “On seeing this,” Nurse O’ Farrell revealed later, “my heart sank.” Still in silence he turned to her and shook hands. She saw him no more.’

The article continues: ‘Miss O’Farrell and her great friend Miss Julia Grennan, spent a few days with us in May 1956. If you examine the photograph of Pearse surrendering to General Lowe, you will notice the shoe and dress of a nurse on the far side of Pearse. She told us that when she saw a British soldier getting ready to take the photo, she stepped back beside Pearse so as not to give the enemy press any satisfaction. Ever after she regretted having done so.’

Pearse was driven to army headquarters in Parkgate Street, where he met General Sir John Maxwell and the actual surrender order was signed. The indefatigably brave Elizabeth O’Farrell, in British custody, went on to deliver the news of surrender to Commandant Daly in the Four Courts later that day, and the other garrisons the following day.

Location of the Meeting between Lowe and Pearse

Where did the meeting between Pearse and Lowe take place? According to Captain de Courcy-Wheeler’s account[4]

‘At 2.30 pm Commandant-General Pearse surrendered to General Lowe accompanied by myself and Lieutenant Lowe at the junction of Moore Street and Great Britain Street. He handed over his arms and military equipment. His sword and automatic repeating pistol in holster with pouch of ammunition, and his canteen, which contained two large onions, were handed to me by Commandant-General Pearse.’

The video by the Dublin historian Éamonn Mac Thomáis[5], recounted that ‘the late Nurse Elizabeth O’Farrell, who was a friend of mine, brought me and Julia Grenan down here on a bit of a tour of the 1916 area. Now when she came around here, she brought me right around like that. She said stand there. Now says she, you are standing in the spot where Patrick Pearse surrendered and handed over his sword to General Lowe. And Julia Grenan said “it was a surrender, it wasn’t defeat! “ ‘

The location would be in line with the rather folksy account in The Dublin Rover[6] by Séamus Scully.In this he states that Pearse:

‘In his heavy military greatcoat and Boer-shaped hat he marched down towards the barricade; the nurse almost trotting by his side. Here he was received by General Lowe, to whom he handed his sword, pistol and ammunition, also his tin canteen which contained two large onions. On the footpath, outside of Byrne’s shop at the corner of Moore Street and Parnell Street, an old wooden bench, which was used for displaying pickled pig’s heads, was brought out from the shop; here Pearse stooped and signed the document of surrender which had been placed on it.’

Thom’s 1915 Directory indeed shows J. Byrne & Co, Grocers and purveyors at No. 58 Parnell Street, at the corner of Moore Street. Incidentally and interestingly the account tells that Pearse actually signed a surrender document.

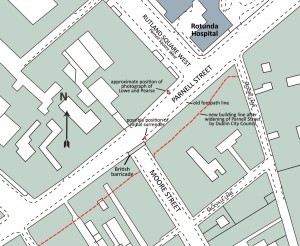

Thus it is likely that the first part of the surrender proceedings did occur on the footpath on Parnell Street, just by the eastern intersection with Moore Street (point A on the map). This is in accordance with the accounts by O’Farrell, de Courcy-Wheeler, Mac Thomáis and Scully.

The photograph of Pearse standing in front of General Lowe was probably taken just after this episode. The party must have walked across to the footpath on the other side of the road. Point ‘B’ on the map indicates the location where the photograph was taken. It was taken, looking east, with the protagonists standing on the footpath.

British troops sit at street level on the right of the footpath. The top of the Parnell Monument can be seen in the background. The building to the left, alas, has been long demolished to make way for some unlovely reconstruction. The Parnell monument can be seen (visible between Lowe and Pearse, in the background). One can gauge reasonably accurately the location on the footpath where the scene between Lowe and Pearse took place. It was just by the Kingfisher Restaurant (as it happens, this was destroyed by fire on 26th February 2016).

Incidentally, there is a crude sign at the junction of Parnell Street and Moore Lane, posted on Conway’s Public House (now closed) which states that this was the location of the surrender. There is no evidence that it was at that particular point. I suggest that that sign be removed and a high-quality plaque be erected on the corner of the building on Parnell street and Moore Street, nearest to where the first surrender event took place.

Who took the Photograph?

The RTE Cashman Collection records that image was taken by ‘an amateur photographer who was a British Army officer at the scene, who gave the negative to Joseph Cashman’.

In the course of my research for images for my illustrated history of 1916, ‘Courage Boys, We are Winning’, I sourced and viewed an original print of this scene in the National Photographic Archives. The print, which I assume came from the original negative, was of a small size (approximately 6×9 cm) and of very poor quality. This would indicate that it was of amateur box camera type, rather than a more formal glass plate camera mounted on a tripod. In any case it is improbable that in the chaos of the surrender moment there would have been time to set up such a camera.

This image, while dramatic, is of very poor quality. It has been heavily doctored in later manifestations. Some versions show the young Lowe smoking a cigarette and there is the issue of O’Farrell’s skirts (of which more later). I received a high resolution scan of this original sepia print from the National Photographic Archive. Using Adobe Photoshop filter tools, I endeavoured to improve the extremely poor quality negative into something recognisable, without altering essential detail in any way. I think I have improved it, as shown.

In the image, from left to right, are Lieutenant John Lowe (later to be known as John Loder, the uxorious Hollywood actor), Brigadier General Lowe and, facing him, Patrick Pearse. O’Farrell’s feet and skirt can be seen behind Pearse.

Airbrushing

As we approach the centenary of the Rising, there has been a tendency to over-analyse some of the facts, adding two and two to come up with ten. One example is the subject of ‘airbrushing’ out O’Farrell. Whether women were airbrushed from the story of the Rising is another issue: their input has recently been comprehensively and ably described by such historians as Liz Gillis.

On O’Farrell and her visibility in the image: firstly, by her own account as above, she deliberately kept behind Pearse, so the main part of her body was never visible. This photograph was used on the front page of the London Daily Sketch (10th May 1916).

O’Farrell’s feet were indeed deleted from some versions of the photograph but there was no underlying gender-based or political agenda for this removal.

Here, O’Farrell’s feet were indeed deleted. The newspaper’s sub-editor had painted out the feet and skirts of O’Farrell (using special ink and an artist’s brush, a technique more likely used then than that of an airbrush – a much later technique). There has been a suggestion that O’Farrell was painted out for fear of the effect it would have on Irish men fighting for Britain to see their women fighting for Ireland at home. There is no underlying source or proof for this assertion.

As far as I know the Daily Sketch is the only primary periodical where the airbrushed version was published. Later versions of the image (such as the 1966 Capuchin Annual) show the original image, with feet and skirts –taken obviously from the original negative. The assertion of ‘fear of Irishwomen fighting’ perhaps amounts to a conspiracy-based view of the world; in my opinion there was no underlying gender-based or political agenda for this removal.

It is likely that the harried Daily Sketch specialist quickly tidied up a poor-quality image, to result in a more dramatic and suitable form for the front page. Other elements, such as the very crisp-looking paving slab joints on the footpath and the detail of the Lowe’s puttees have been painted in. it was probably quite a rapid alteration – General Lowe’s face looks quite odd. Touching up like this was a very common feature of photographs in newspapers of that era (and many fairly crude examples of this abound in newspaper archives).

In the same vein of over-analysis, there was a piece by an expert from the National Museum of Ireland, speaking on the TG4 programme, ‘Réabhlóid’ (Episode Four)[7]. It was recounted that the museum had recently acquired a small sepia image of the surrender scene (it looks similar to the original sepia print I had viewed in the National Photographic Archive).

Using colour analysis, the expert had deduced that what looks like Pearse’s greatcoat was in fact O’Farrell’s outer cape, and that Pearse was not wearing a greatcoat, but only his Volunteer’s uniform. This new interesting interpretation sent me on an exploration of this proposition. I used the colour filter technique applied, in different permutations, to the sepia image.

However, try as I might, I could not see any change to the basic image – although possibly a narrow line of O’Farrell’s cape, proud of the line of the greatcoat, may be visible at the rear. Sometimes, the simplest solution is the answer: that in the scene Pearse was standing in his greatcoat, with O’Farrell mostly obscured, save principally, her feet and skirts below. There is evidence that Pearse had a greatcoat with him. Wexford Volunteers were later driven to Dublin to confirm the surrender: The witness statement of one of these, Seamus Doyle[8], tells of meeting Pearse in his cell in Arbour Hill Detention Barracks: ‘Pearse was lying on a mattress in the cell covered by his greatcoat.’

A dramatic symbol or incarnation of the end of the Rising, this is a hugely important photograph. It has been published widely, but on occasion erroneously interpreted. However, together with testimonies like O’Farrell’s, the photograph yields an interesting insight into the end of the Rising. The evidence also indicates that the surrender proceedings (from initial surrender to the taking of the photograph) were spread out over both sides of Parnell Street.

References

[1] Catholic Bulletin, 1917, p 267: ‘Miss Elizabeth O’Farrell’s Story of the Surrender’ (Note: some accounts of the time use the previous name Great Britain Street. The street had been renamed ‘Parnell’ after his death in 1891).

[2] Catholic Bulletin, 1917, p 269

[3] An Fiolar, Golden Jubilee issue of An Fiolar (published by Mount St Joseph College, Roscrea), 1958

[4] Findlaters; the Story of a Dublin Merchant Family (1774‒2001), by Alex Findlater. Chapter Nine, the Easter Rising.

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DvHxSdyH8Pk dating from several decades ago, shows Mac Thomáis walking to that precise location on the footpath on Parnell Street, just by the eastern intersection with Moore Street. (Note that the video was made before the road was widened – the footpath does not exist now. The southern side of Parnell Street was demolished for road widening decades ago and there is a new street-line).

[6] Page 92, The Dublin Rover by Séamus Scully, Tara Books, Dublin, 1991 (Scully does not give sources, but he had an excellent knowledge of Dublin’s history, and displayed an intimate knowledge of the history of Moore Street)

[7] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DvHxSdyH8Pk

[8] BMH WS 315