Dublin in 1913

In this first of two interviews with Padraig Yeates, journalist, historian and author of Lockout: Dublin 1913, we talk about the Irish capital on the eve of the largest and most bitter strike in Irish history, the Lockout. (Second interview here) By John Dorney

In this first of two interviews with Padraig Yeates, journalist, historian and author of Lockout: Dublin 1913, we talk about the Irish capital on the eve of the largest and most bitter strike in Irish history, the Lockout. (Second interview here) By John DorneyListen to the interview here.

Dublin in 1913 was a city that had witnessed almost a century of economic stagnation since the Act of Union stripped it of its role as seat of the Irish Parliament in 1800.

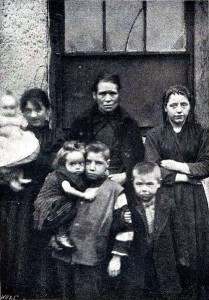

Wages were low, housing conditions for the working classes were poor and emigration was high

Low economic growth had meant that there was, as Padraig puts it, a large pool of unemployed casual labour which employers could and did exploit quite ruthlessly.

Wages were low, housing conditions for the working classes were poor and emigration , mostly to the cities of northern England, was high.

At the same time, the city was spreading from its 19th century core to encompass new, middle-class suburbs like Clontarf and Rathmines.

If the gap between rich and poor was one explosive ingredient in Dublin’s mix, another was the city’s stark sectarian divide. Much more so than today, there was a large and self-conscious Protestant community there – which Padraig describes as an “inverted pyramid”, with its largest sector at the top echelons of society.

Catholic businessmen like William Martin Murphy, the owner of the Irish Independent newspaper and the Dublin United Tramway Company, were just beginning to challenge the dominance of this elite.

Into this mix arrived a new generation of socialist trade union activists, led by James Larkin who founded the Irish Transport & General Workers’ Union in 1909. Padraig describes the impact this “new unionism” had in organizing low skilled workers.

The confrontation between Larkin and Murphy, Padraig argues, was in equal parts a class struggle and a clash of personalities. Either way, it put the Dublin organised working class and the employers – united across the sectarian divide – onto a collision course which ended in the Lockout. the Lockout exposed many of the contradictions that underlay both British rule in Ireland and Irish nationalism itself

But this was not all that was happening. Ireland stood at the brink of Home Rule or self-government. And the Lockout exposed many of the contradictions that underlay both British rule in Ireland and Irish nationalism itself.

Padraig argues that the indecisive role of the Irish Parliamentary Party undermined its support both among the organized working class and the Catholic middle class.

Socialism was generally regarded with distaste by Irish nationalists who saw it in Padraig Yeates’ words , “as part of Anglo-Saxon materialism that was destroying Gaelic civilization”.

On top of that, just before the outbreak of nationalist insurrection in the Easter Rising of 1916, the violent behaviour towards the workers of the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP), who were controlled directly by the British administration in Dublin Castle, opened a breach between Police and community that never had time to heal.

For all of these reasons, the Lockout of 1913 was a pivotal event in Dublin’s and to an extent, Irish, history.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download