Four Bloody Sundays

In the wake of the Saville Report on the events in Derry in 1972, John Dorney looks at the place of “Bloody Sundays” in 20th century Irish History.

~

It may surprise some readers to learn that there were not two, but four ‘Bloody Sundays’ in 20th century Irish History.

Dublin 1913

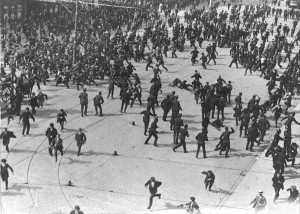

The first came in the Lockout, the great industrial dispute of 1913. On August 31, the Dublin Metropolitan Police and RIC baton-charged a crowd on O’Connell Street, Dublin, who were gathered to hear a speech by the fiery trade union leader Jim Larkin.

Most of those injured were not in fact trade unionists, who were at a rally elsewhere in the city, but mere bystanders –showing how indiscriminate the police action was.

Several hundred people were injured and there was ferocious rioting all over working class districts of Dublin that night and over the following days between trade unionists and the police. In the labour tradition, this is “their own” Bloody Sunday. One can still see on Siptu banners the names of the “martyrs”, James Nolan and James Byrne, beaten to death by the police over that weekend.

Over 3,000 people, led by union marching bands, attended Byrne’s funeral as a mark of defiance.

Dublin 1920

Many more people will be aware of the next Bloody Sunday, which happened during the Irish War of Independence in November 1920. Of the four incidents, this was the bloodiest, with at least 31 deaths. We can immediately see the difference between even a bitter industrial dispute and an armed nationalist conflict in a comparison of 1913 and 1920.

In 1913, there were limits on the violence, sticks, batons and hurleys were used in fighting, but guns hardly ever. Those who did die were killed somewhat by mistake, in over zealous beatings. In 1920, however the restraints in violence were removed to a much greater degree – belligerents on both sides set out to kill.

Michael Collins had been alarmed by the growth of British Intelligence in the Dublin, and with hair-raising ruthlessness, drew up a list to wipe it out. Early on the morning of Sunday, November 21, 1920, teams of killers from Collins’ “Squad” and the IRA Dublin Brigade, visited over a dozen private addresses in the south of the city. By the time the capital had woken up, 14 people were dead, eight of them British agents, two Auxiliaries the rest either bystanders or civilians informers.

The operation was ugly, but as an act of terror – that is to frighten the British administration and those who collaborated with it, it had no equal. Agents could be seen over the following days under military escort, moving into Dublin Castle, away from hostile eyes and hidden revolvers.

Irish memory of the day might be tinged with some regret had it not been for the British forces’ reaction

Had this been the end of the day’s events, Irish memory of the day might be tinged with some regret. But the British forces’ reaction ensured that “Bloody Sunday” would be remembered not as a cold-blooded assassination but as a British atrocity.

A mixed force of RIC and Auxiliaries raided a Gaelic football match at Croke Park – only a couple of miles across the city from the morning’s killings – looking for suspects.

Once inside the ground, whether out of panic or as a deliberate reprisal, they opened fire indiscriminately and killed some 14 people – one of them a player. Another three republican prisoners, Peadar Clancy, Dick McKee and Conor Clune, were also murdered in Dublin Castle that night, supposedly, “while trying to escape”.

For a longer consideration of the day’s events see Bloody Sunday 1920 Revisited.

Belfast 1921

The third, and probably least well-remembered, Bloody Sunday takes us north from the Irish capital to Belfast – the newly established capital of Northern Ireland – in July 1921.

The Irish War of Independence is not usually associated with Belfast. People are far more likely to think of ambushes in rural Cork or Black and Tan reprisals in small southern towns. And yet the northern city was, behind only County Cork, the part of Ireland worst affected by the conflict. Some 450 people lost their lives there and over 1,000 were wounded – most of them in late 1921 and early 1922 – a time of “Truce” in the rest of the country.

Belfast’s Bloody Sunday took place on July 10th 1921, just a day before the Truce between the IRA and the British was put into effect. The IRA in the city alerted by the banging of nationalist dustbin lids on the ground (an iconic symbol of resistance among the northern minority) mounted a successful ambush of an RIC armoured car on Raglan Street on July 9.

The following day, Sunday July 10, central and west Belfast became a war zone as loyalists, incensed by the ambush but no doubt also fearful of “sellout” in the Truce, attacked the Catholic enclaves.

Loyalist groups, the police and the IRA blazed away at each other with rifles, machine guns and even grenades.

Loyalist groups (many armed since before the First World War), the police and IRA blazed away at each other from rooftops, windows and street corners with rifles, machine guns and even grenades. Rival Catholic and Protestant mobs exchanged stones and petrol bombs. By the time the day was out, 16 civilians were dead and 161 houses destroyed. The sectarian body count was heavily in the Protestants’ favour – 11 Catholics for 5 Protestants and 150 Catholic houses destroyed for 11 Protestant’s.

The toll in the following days could have been worse still, had not Eoin O’Duffy, at that time Michael Collins’ man in Ulster, been sent to the city to make sure the IRA adhered to the Truce. The British, for their part, announced a strict curfew so that the Twelfth, just two days after “Bloody Sunday”, would pass off peacefully. In reality however, the events of July 1921 were harbinger of the most lethal phase of Belfast’s first “Troubles”.

Derry 1972

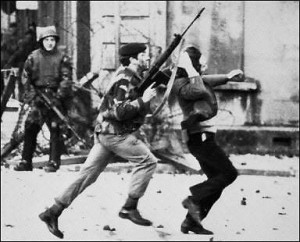

The final Bloody Sunday moves us west and forward some 50 years to Derry in January 1972. Derry had been experiencing severe civil unrest since 1968, arising out of the Civil Rights campaign for more equal treatment for Catholics in the Northern state. However, unlike its predecessor in 1921, the final Bloody Sunday was not a clash between rival sectarian groups, armed or otherwise, but a massacre of Catholic civilians by British state forces.

Unlike all of the previous Bloody Sundays, this was a clash solely between British forces and Irish nationalists, and unlike the previous three, the deaths and injuries were all on one side. From this the Derry events derived their distinctive emotional punch.

On January 30, 1972, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association called a protest in Derry against the internment of (almost exclusively Catholic) paramilitary suspects. The march was banned on the recommendation of the British Army, although the RUC Chief Superintendent Frank Lagan said it should go ahead.

Unlike the previous three events, the dead and injured on Bloody Sunday 1972 were all on one side

The march mostly passed off peacefully after Army barricades prevented the 15,000 marchers from leaving the nationalist Bogside and passing into Derry’s city centre but a small number of youths began to throw stones at the soldiers.

Some British troops, acted with relative restraint, and used rubber bullets, tear gas and water cannon. However the Support Company of the 1st Parachute Regiment, was sent by their officer, Colonel Wilfred, chasing the rioters down into the maze of terraced streets and flat complexes on Rossville street to make arrests. This was against explicit orders from Wilfred’s superiors, who had ordered him not to pursue suspects into the Bogside, where they could not be distinguished from peaceful demonstrators.

The soldiers claimed they were fired on, but it now seems (according to the Saville Inquiry), that they were panicked by shots fired over the heads of the crowd by their own Lieutenant. They then opened fire, firing 100 shots from their SLR rifles in and around the flat complexes of Rossville Street, Glenfada Park and Abbey Park, killing 13 people and injuring a similar number.

Derry activist Eamonn McCann wrote, “After Bloody Sunday, the most powerful feeling in the area was one of revenge…people made a holiday in their hearts at the news of a dead soldier”. The shadow of Bloody Sunday was long enough and dark enough to help keep the Provisional IRA’s campaign going for over 20 bloody years.

What do these events have in common?

After all, there were dozens, if not hundreds, of violent days both in the 1920s and in the 1970s in Ireland. What makes these four so special?

Firstly, the fact that they took place on Sunday is significant in terms of popular memory. Sunday, especially in the early 20th century, was a day of rest. It was the only day of the week when most people did not have to work and it was for this reason that events like the rallies in Dublin in 1913 and Derry in 1972, as well as the football match in 1920 took place on that day. Irish society was also still extremely religiously observant at all of these junctures.

Violence on a Sunday was a particularly jarring disruption of everyday life

So the introduction of brutal violence into everyday life on a Sunday was a particularly jarring disruption of normal life – shattering people’s sense of security and mental balance. If the peace of God on Sunday could be violated, when was it safe?

Secondly, three of the four incidents, 1913, 1920 and 1972, were, in whole or in part, acts of violence committed by British state forces on Irish civilians. For this reason, the term “Bloody Sunday” carries with it an air of reproach on the British state in Ireland, which could be characterized as brutal and tyrannical as a result.

The Croke Park shootings in 1920 helped the Irish Republic to broadcast itself as an outraged victim of British imperialism across the world. The Paras’ shooting spree in the Bogside in 1972 made the Provisional Republicans’ argument – that armed struggle against the British presence in Ireland was the only worthwhile course of action – a lot more credible to young northern Catholics.

Even the 1913 version, which, being less bloody and concerning a much more limited constituency (that of trade unionists specifically) is less well remembered than 1920 or 1972, it retains its power in certain labour circles as a symbol of the suffering undergone for the establishment of that movement.

The Bloody Sunday of 1921, on the other hand is all but completely forgotten. In one way this is strange, as the number of fatal victims is second only to 1920 and the extent of material damage was much greater than any of the other incidents. And yet, Belfast’s Bloody Sunday does not fit so well into a story anyone wants to remember.

Factional butchery in west Belfast suits no one. Not republicans – who see their century-long struggle as being against British imperialism and would prefer not to concentrate on Catholics fighting Protestants. Not unionists – who would rather not be reminded of collective loyalist reprisals on Catholics. Not even the British, for whom the incident could perhaps be used to frame the 1920s as a sectarian bloodbath with itself as neutral arbiter.

The power of the various Bloody Sundays as memories depends on how easily they can be retold as part of someone’s narrative of Irish history.

In the end we can see that the power of the various Bloody Sundays as memories and as spurs to action depends not only on how bloody they were, or how obscenely the Sabbath was violated, but on how easily such events can be retold as part of someone’s own narrative of Irish history.