Policing The Dublin Fog

Barry Kennerk writes about the trials and perils of Dublin’s Victorian Policeman.

Barry Kennerk writes about the trials and perils of Dublin’s Victorian Policeman.

‘Now the city sleeps: wharves, walls, and bridges are veiled and have disappeared in the fog that has crept up from the sea; the shameless squalour of the outlying streets is enwrapped in the grey mist’ – thus wrote Irish writer George Moore of Dublin in A Drama in Muslin.

Although Londoners consumed more coal per capita than their Irish counterparts, Victorian Dublin was still burdened with at least fifty days of charcoal-smelling smog each winter. Immortalised in the shanties of sailors who lay at berth, it could be more than just a nuisance and during heavy spells, newspapers were peppered with reports of tragic drowning accidents in the Royal or Grand Canals. Cross-channel mail steamers were delayed and the GPO was obliged to employ an army of special sorting staff and postmen to meet the bags when they arrived. A late nineteenth-century sea-faring ballad ran thus:

Oh, the sun may shine through a Dublin fog,

And the Liffey run quite clear,

Or a p’liceman when wanted may be found,

Or I may forget my beer my boys,

Or the landlord’s quarter day,

But I can’t forget my own true love,

Ten thousand miles away.

Until the late 1860s, there were no fog horns in Dublin Bay. Instead, the low chime of a bell could often be heard tolling in the mouth of the Liffey estuary. On particularly bad nights, the fog seeped through the casement sashes and door jambs of the city’s houses. It was so common an occurrence that Irish writer Donagh MacDonagh chose it as the first line of one of his poems, beginning with: ‘Fear, like a fog, slips in at every window’.

It was so common an occurrence that Irish writer Donagh MacDonagh chose it as the first line of one of his poems, beginning with: ‘Fear, like a fog, slips in at every window’

For the policeman obliged to work in such conditions, the streets were no safer than they had been when eighteenth-century bucks and cutthroats went on the prowl. Gas lamps cast eerie rainbow-like auras. Like the constable’s bull’s eye lantern, they were of little practical use.

In 1867, a letter writer to The Irish Times complained that most of the lights on the North side of Stephen’s Green were broken, as were those along Kildare Street, Merrion Row and Baggot Street. When a heavily laden dray was overturned in Lower Abbey Street during the carters’ strike of November 1908, the fog was so severe that it prevented the police from making any arrests.

When a heavily laden dray was overturned in Lower Abbey Street during the carters’ strike of November 1908, the fog was so severe that it prevented the police from making any arrests</strong>

Each evening, the constables marched out from their stations at nine o’clock. The public houses closed at eleven and, with the withdrawal of the horse-drawn omnibuses, the streets were usually deserted and silent. New recruits, known colourfully as ‘Johnny Raws’, were left to police Dublin’s wheel-rutted laneways with the more experienced officers patrolling the main thoroughfares. Each was furnished with a book, written out in the way that the beat was to be taken and at times were encouraged to forfeit gunpowder-made fog signals from unlicensed premises wherever they found them.

The police commissioners allowed the men to grow beards as protection against the cold and wet and if the nights were particularly bad, they might seek shelter in a cabman’s shelter. Misguided connections were made between fog – sometimes called ‘blue-mist’ and cholera but, regardless of the actual cause, chronic lung conditions were rife. The Irish Times regularly carried advertisements for ‘Holloway’s Pill’s as a remedy against ‘suffocating fogs’ and in 1849 the Quarterly Journal of Medical Science remarked that it was unfair to reduce the salaries of sick officers – those men who chose to walk their beat ‘instead of skulking under an archway’. Unable to afford the double blow of medical expenses and loss of pay, they often chose to avoid the doctor with lethal consequences.

When ‘Fenian Fever’ descended over the city during the late 1860s, gunmen sometimes used the fog to move weapons or documents between ‘safe’ houses and at other times, the force was obliged to contend with opportunistic burglaries or with jack-booted smugglers as they hauled their cargos up the Tolka at Mud Island near Ballybough.

When ‘Fenian Fever’ descended over the city during the late 1860s, gunmen sometimes used the fog to move weapons or documents between ‘safe’ houses

At other times, there were safer and more rewarding moments when beat constables were able to come to the help of people who lost their way. Beginning in the late nineteenth-century, The Irish Times ran a regular column called ‘Granny’s Corner’. Aimed at children, the stories covered the lighter side of life, some of which inevitably centred on Dublin’s perennial winter weather. ‘It was lucky you met that invaluable policeman’, the writer once enthused. ‘A fog is the most bewildering thing in the world. I am sure you were glad to see the lights of home again – Your affectionate GRANNY’.

About The Author

About The Author

Barry Kennerk is the author of In The Shadow Of The Brotherhood: The Temple Bar Shootings. He is a post-graduate student affiliated with St Patrick’s College, Drumcondra, researching the Fenians. His first book, The Railway House – Tales From an Irish Fireside, was published in 2008. He works at the Children’s University Hospital, Temple Street. He is married with two children and lives in Ashbourne, County Meath.

Image Credits

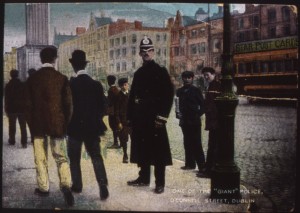

Main image courtesy of the Dublin City Library and Archive (Dixon Slide 40.25) ‘one of the Giant’ police, 1908.

Author image, courtesy of Mercier Press.