The 1641 Depositions go online

John Dorney reports from the launch of the 1641 Depositions online at Trinity College

John Dorney reports from the launch of the 1641 Depositions online at Trinity College

Some time in the winter of 1641, Anne Butler found her household in Carlow attacked and robbed by groups of armed men. They told her that her family had been targeted because they “were rank puritan Protestants”.

Not long after, rumours reached her from Jane Jones, who said she had seen “35 English going to execution”, including women and children.

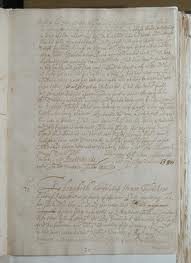

Her testimony was one of some 8,000 statements collected in the Depositions by Henry Jones in early 1642 of attacks on Protestants in the early months of the rebellion.

On October 22nd, 2010, exactly three hundred and sixty nine years after the outbreak of the 1641 rebellion, Trinity College saw the formal launch of the Depositions – now for the first time published both in print and online in digital form.

Three hundred and sixty nine years after the 1641 rebellion, the Depositions – eyewitness accounts from Protestant victims of the rebellion – have been published.

Professor Jane Ohlmeyer, who has overseen the project, said that the Irish, “are one of the few nations who still have the 17th century in our DNA”. And certainly, the fact that the Depositions have remained in manuscript form for so long, in rolls and rolls of hastily hand-written and scratchily corrected sheets, says something about their continued explosive potential in Irish politics for over three centuries.

The rebellion of 1641 and particularly the killings of Protestant civilians, was the justification for the Parliamentarian conquest of Ireland in 1649-53, which saw land, wealth and political power pass decisively from the older, Catholic elite to the Protestant settlers.

More than that, it became a symbol for Protestants of Catholic iniquity and a reason to exclude them from political power. Even today, the narrative that peaceful Protestants were the subject of an unprovoked and pre-planned massacre in 1641 still has emotional force in the context of sectarian divisions in Northern Ireland. Equally, for the Catholic nationalist tradition, which would prefer to see their ancestors as victims of colonization rather than as persecutors, the material in the Depositions is troubling.

(See for instance, this Catholic and nationalist account of the rebellion from 1905)

The Irish Free State refused to publish the Depositions without first censoring them in the 1930s

The Depositions, Professor Ohlmeyer reminded her listeners, are a biased source. They cover only the suffering of Protestants and not the Government and Protestant retaliation against Catholics, which certainly claimed as many lives as did the initial killings.

The Depositions, Professor Ohlmeyer reminded her listeners, are a biased source. They cover only the suffering of Protestants and not the Government and Protestant retaliation against Catholics, which certainly claimed as many lives as did the initial killings.

Professor John Morrill of Cambridge said that, “we will never know exactly how many died” in 1641-42 and while there was, “no pre-planned slaughter”, it was certainly, “the greatest recorded massacre” in either British or Irish history.

Professor Morrill stressed the need to separate eyewtiness testimony and hearsay in the Depositions

However, what the deponents heard second hand, in terrifying rumours passed between the refugees as they crammed into Dublin and the port towns, was a nightmare scenario of massacre, torture, rape and the killing of women and children.

Professor Morrill argued that the Catholic elite, including the clergy, “lost control” in the first few months of the rebellion and the result was that the Protestant settlers bore the brunt of popular fury.

Professor Morrill argued that the Catholic elite, including the clergy, “lost control” in the first few months of the rebellion and the result was that the Protestant settlers bore the brunt of popular fury.

However, the version popularised in England, where parts of the Depositions were circulated and where one third of all publication in 1642 concerned the massacres in Ireland, was that of a premeditated and sadistic massacre, orchestrated by the Catholic clergy.

One result of popular outrage in England was the Adventurers’ Act, by which Catholic lands in Ireland were confiscated to pay for the raising of an army to put down the rising. Another, more long term, result was the actual Cromwellian re-conquest of Ireland some seven years later.

Professor Morrill suggested that Cromwell himself did not deserve his reputation as persecutor of the Irish Catholics. His massacres at Drogheda and Wexford were terror tactics designed to discourage resistance rather than acts of religious or ethnic vengeance. He tried to mitigate the harshness of the post-war settlement and confine punishment to the leaders of the rebellion. Far more vengeful was Henry Ireton, who took over command in Ireland from Cromwell and who was in favour of a draconian settlement, with mass executions and deportation west of the Shannon.

Ben Kiernan of Yale University talked about comparable episodes of mass killing in contemporary south east Asia – a reminder that Ireland is by no means the only country to have a bloody past.

The Depositions are now available online and the manuscript can be viewed in hte Long Library at Trinity.

The Depositions project started in 2005 and has involved scholars from Trinity, Aberdeen and Cambridge, as well as linguists and technical experts – in total over 50 people. It was supervised by Jane Ohlmeyer and Micheal O Siochru, two of the most distinguished historians of early modern Ireland.

The Depositions are online at http://1641.tcd.ie/ and the manuscripts are currently on display in the Long Library in Trinity College. The official launch of the Depositions was attended by the President, Mary MacAleese, and by Democratic Unionist Party leader Ian Paisley.

Also see Irish History Podcast’s take on the Depositions here.

~~~~~~~

Image Credit:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Some rights reserved by Pochade_Lad