‘The distinction is a fine but real one.’- Sectarianism in County Clare during the War of Independence

Padraig Óg Ó’Ruairc looks at the existence or lack thereof of sectarian violence in Clare during the War of Independence. For more from Padraig read his books, or his excellent website.

Padraig Óg Ó’Ruairc looks at the existence or lack thereof of sectarian violence in Clare during the War of Independence. For more from Padraig read his books, or his excellent website.

Recent work by historians such as Peter Hart, and opinion pieces by media commentators including Kevin Myers and Eoghan Harris have claimed that the I.R.A. in the south of Ireland was motivated by sectarianism and conducted a campaign of ethic cleansing against Protestants during the War of Independence. Hart has stated that ‘sectarianism was embedded in the Irish revolution, north and south.’ [1]

This has been used to insinuate that sectarianism and ethnic cleansing were a general characteristic of the war itself throughout Ireland – thus challenging the legitimacy and morality of the whole War of Independence. These claims have proved highly controversial and have already been publicly challenged by a number of historians including Meda Ryan, Brian Murphy and John Borgonovo. However I feel it is necessary to ask whether any of these claims prove true in relation to the War of Independence in Clare (The Irish Story has covered some of these issues generally here, here and here).

Background

According to the 1911 census, County Clare had the smallest Protestant population of any Irish county, 98.14% of the population were Roman Catholic. There were just 1,913 Protestants in the county, of whom 1,709 belonged to the Church of Ireland.

In September 1911, two Protestant members of the County Clare Unionist Club, Colonel George O’ Callaghan Westropp and Henry Valentine Macnamara, addressed a meeting of the Hollywood Unionist Club in Co. Down. O Callaghan was a former Lieutenant Colonel in the Clare Artillery and a landlord with two hundred tenants. Macnamara owned a 4,000 acre estate in North Clare on which there were five hundred tenants. He was later appointed High Sheriff of Clare. I.R.A. Veteran Thomas Shaloo later described him as ‘… a most unpopular landlord and a bitter enemy of Sinn Fein…’ [2] Macnamara claimed at this meeting that Protestants in Clare were subject to boycott, discrimination and sectarian attack.

‘If the Protestants did not bow to the dictates of the United Irish League their lives were made most unpleasant. … A man’s children he added were liable to be annoyed by Catholic children and he was subject to the receipt of threatening letters and continuous pinpricks of that sort were even harder to bear than big troubles. If the victim were a shopkeeper his windows were broken: if a farmer his cattle were maimed, and if these outrages did not prove sufficiently effective, shots were fired into his house, and even attempts at murder were made.’ [3]

Macnamara’s comments provoked outrage when they were reported in Clare. The Clare Champion newspaper received letters from fourteen Protestants living in Clare, including six members of the committee of the Clare County Unionist Club repudiating Macnamara’s claims of sectarianism. These were: R.J. Stackpoole, William B. Smith, Nicholas C. Philpot, A. Capon, F.N. Studdert, Robert Russell, James Butler Ievers, F.C. Pilkington, W.C. Doherty, Michael Cullinan O’ Halloran, Michael Tottenham –Brew, H.B. Harris. Doherty described Macnamara’s claims as a ’tissue of falsehoods’, Stackpoole declared:

‘during that part of my life-time I spent in this county, no Roman Catholic has ever in any way interfered with or upbraided me on the subject of my religion’ [4]

Pilkington claimed:

‘I have never met with the smallest inconvenience or discourtesy from my Roman Catholic brethren on account of my religion. On the contrary, I have lived all my life among them, on terms of the best friendship and goodwill. It is my experience that our county is happily free from religious intolerance, and if anyone here has been subjected to persecution it is not on account of his religion but for some other reason.’ [5]

Several of the Protestant letter writers, Like Macnamara, had been elected to local councils and were quick to point out that since less than 2% of the county’s population were Protestant that if the Catholic voters of Clare were religious bigots then neither they nor Macnamara would ever have been elected. Russell who topped the poll despite the fact that there were only two other Protestant voters in the district stated:

‘I defeated three Nationalist and Catholic candidates of good standing, and sit now on a Board with two other Protestants, also elected by Catholic and Nationalist voters, where we receive the greatest courtesy and kindness from the majority who differ from us in religion.'[6]

Tottenham –Brew reminded Macnamara that he hadn’t been elected by ‘the drum beaters North of the Boyne’. [7]

John M. Regan, a member of the R.I.C. stationed in Clare at the time, claimed that Macnamara ‘did not stick strictly to the truth about the state of affairs in Clare.’ Apparently Macnamara took the rebuke from his co-religionists badly and had several poems and song verses written criticising them. Regan remembered that these though amusing sometimes were ‘bordering on the libelous.’ [8] Beyond being patron to such satire, O’ Callaghan and Macnamara paid little head to their critics and in January 1914 the Belfast newspaper The Irish News wrote that O’ Callaghan and Macnamara were once again issuing; ‘like rats from their holes, of defamation all over Ulster against the people of Co. Clare.’ [9]

Later, during the War of Independence itself, an English veteran of the Great War turned reporter Wilfrid Ewart toured Ireland in April and May of 1921. Although he did not visit Clare, Ewart did interview the Protestant Dean of Limerick who told him ‘Personally I am on the best of terms with all the farmers about here, Sinn Feiners, Nationalists, or what not.’ When Ewart asked him if there were any ‘religious differences’, the Dean replied ‘There are none. Please disabuse yourself of that idea. I personally am on the best of terms with all my colleagues. There is perfect accord between Protestants and Roman Catholics.’ [10]

R.C. Grey a retired English Civil Servant living in Killaloe at the same time claimed:

‘There are of course many Sinn Feiners in the neighborhood, as there are in every part of Ireland, but they are not aggressively or openly active, and they certainly never exhibited the slightest animosity towards the Unionists who live round about.’ [11]

Undoubtedly there must have been some religious bigots of both denominations in Clare at the time, however the above comments show that sectarianism was not a prominent or defining feature of life in Clare at the beginning of the War of Independence.

Protestant Republicans

Protestant Republicans

Although support for the I.R.A. and Sinn Fein in Clare during the War of Independence was overwhelming Catholic it was by no means exclusively so. This reflects the fact that the war was not at its core about religion – the central issue being the political question of independence for Ireland. Though the majority of Clare Protestants were pro-British loyalists, a small number of Clare Protestants were active republicans in the period. These included Maire de Buitleir an Irish language activist with Conradh Na Gaeilge who helped Arthur Griffith found the early Sinn Fein party and was credited with naming the organisation. Mary Spring Rice from Limerick was secretary of the Clare board of the Irish Volunteers in the early years of the movement. Ernest Blythe a Presbyterian republican from Lisburn Co. Antrim was appointed an organiser and training officer to the Irish Volunteers in Clare in May 1915. He was so enthusiastic in this endeavour that he was deported under the Defence of the Realm Act within a few weeks.

Ernest Blythe a Presbyterian republican from Lisburn Co. Antrim was appointed an organiser and training officer to the Irish Volunteers in Clare in May 1915. He was so enthusiastic in this endeavour that he was deported under the Defence of the Realm Act within a few weeks.

After the 1916 rising Nelly O’ Brien, who founded the ‘Craobh na gCuig gCuigi’ Irish college at Carrigaholt, endeavoured to organise support for Sinn Fein amongst her fellow Protestants in county Clare. Another Protestant republican Constance Markievicz, who had been sentenced to death for her part in the 1916 rising, played a prominent role in canvassing for Eamonn de Valera and Sinn Fein during the East Clare by-election of 1917. William Charles Doherty was a supporter of Sinn Fein’s anti-Conscription campaign in 1918. Dr. Pearson of Lisdoonvarna, an Ulster Protestant, was very friendly with leading members of the I.R.A.’s Mid Clare Brigade and at great personal risk treated wounded I.R.A. volunteers following the Monreal ambush in December 1920. Pearson was suspected of republican sympathies by the R.I.C. and Black &Tans and was subject to harassment and intimidation on account of this.

British commentary on the nature of the war

The British forces at the time did not accuse the I.R.A. in Clare of being motivated by sectarianism. John M. Regan a Catholic member of the R.I.C. and later R.U.C. was stationed in Clare for five years from 1909 – 1914. Although a full chapter of his memoirs details his time in Clare he does not mention sectarianism being an issue in Clare at the time, although he did comment upon the sectarianism he experienced after being transferred to Fermanagh. Regan observed ‘the further one gets from Belfast the less sectarianism there is generally’.[12]

The Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry was stationed in Clare during the War of Independence. The account of their time in Ireland The 43rd In Ireland in the Regimental Chronicle is very critical of the Irish. Seemingly influenced by the ‘stupid Paddy’, anti-Irish prejudice of the period it describes them as unhinged, queer, dirty, contemptuous, idle, cowardly, vindictive, melodramatic, childish and crooked dagoes, terrorists and murderers. The Regimental Chronicle even accuses the Irish of cruelty to animals! It does not however accuse the Irish of being religious bigots. [13]

Lionel Curtis, a prominent adviser to the British Government who secretly visited Ireland in 1921 wrote;

‘To conceive the struggle as religious in character is in any case misleading. Protestants in the south do not complain of persecution on sectarian grounds. If Protestant farmers are murdered, it is not by reason of their religion, but rather because they are under suspicion as loyalists. The distinction is a fine but a real one.’ [14]

Church Burnings

One disturbing aspect of the War of Independence period in Clare that was undoubtedly sectarian were the arson attacks on Protestant churches in the county. However contemporary documents indicate that the I.R.A. were not responsible for these.

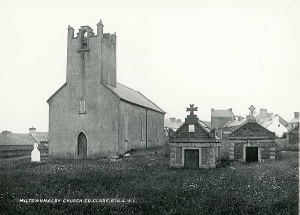

Two Protestant churches suffered arson attacks during the War of Independence in Clare. The Protestant church at Clarecastle was destroyed in a malicious fire on 17 April 1920 the churches was disused at the time, due to the falling Protestant population. It had been reliant on Ordinance workers during the Great War to form a congregation and after their departure the local Protestants attended the surrounding churches instead. The church had been deliberately set on fire with paraffin oil. A resolution of sympathy addressed to the Church of Ireland on behalf of the residents of Clarecastle was drawn up by the local council following the burning of the church. Amongst the signatories was the local Sinn Fein councillor, B. Mescall.

The Protestant church at O’ Briensbridge was also subject to an arson attack on 29 June 1920. The R.I.C. county Inspector’s description of the incident in his monthly report makes interesting reading:

‘The police assisted by some local people including Sinn Feiners, succeeded in getting the fire under control and saving the building. The motive is to introduce religious strife into the present unrest. The clergyman is most popular with all Classes.’ [15]

The County Inspector’s statement that the motive of the attack was to ‘introduce religious strife’ into the war implies that the nature of the war was not sectarian up to this point. Also the fact that ‘Sinn Feiners’ joined the R.I.C. in putting out the fire and saving the church makes it unlikely that local republicans were responsible for the attack.

During the Civil War, the Protestant church at Milltown Malbay was burned down on 14 December 1922. Although this took place a year and a half after the end of the War of Independence, it is significant because some sections of the public assumed that the I.R.A. was responsible. This was sternly denied by the local I.R.A. leader Anthony Malone in a letter to Frank Barrett commander of the I.R.A.’s 1st Western Division.

‘The Protestant Church in Milltown was burned down some time late last night. I have no information to connect any body with the outrage yet. This is the third case of burning of private property within the parish since June 29th outside the I.R.A. Bks. It is the common belief of the public that the I.R.A. are responsible for these outrages. Of course members of the I.R.A. may or may not have taken part in them, but without knowledge or consent of the Batt. Staff. I want to know can anything be done whereby these false reports concerning the I.R.A. can be repudiated. I am opposed to these outrages personally, & I can see that such things are a blow to Republicans.'[16]

There were other cases of attacks on Church of Ireland property in Clare during the War of Independence. However the R.I.C. did not cite ‘religious strife’ as the cause of these incidents. On 5 March 1921 the windows of the Protestant rector’s house at Spanish Point were broken. The trustee of the property Mr. Read had recently hired a caretaker from Kerry and the RIC County Inspector’s report stated that the motive for the vandalism was ‘simply because he did not employ a local man’. The report did not accuse Sinn Fein of involvement in the attack. [17] On 6 May 1921 the windows of the Protestant Church at Feakle were broken. According to the R.I.C. the damage was the result of ‘a spontaneous outburst of hooliganism by some youngsters.’ [18]

Spies and Informers

One of the key arguments made by those who claim that War Of Independence was a sectarian conflict is that the I.R.A. in West Cork and other areas used the issue of spies and informers to mask a sectarian campaign of ethnic cleansing against Protestants. Historian Peter Hart suggested that the I.R.A.’s targeting and execution of spies ‘had little or nothing to do with the victims’ actual behaviour’ but was based instead on their religion, according to Hart as the I.R.A.’s military campaign increased in intensity towards the end of the war ‘…anti-Protestant violence rose along with it.’ [19] Others have claimed that the I.R.A. was ‘unmerciful’ in their treatment of suspected informers. These theories often do not withstand close scrutiny.

Tom Barry’s 3rd West Cork Brigade of the I.R.A. executed fifteen suspected spies during the War of Independence, of whom a majority of nine were Catholic and a minority of six were Protestant. The three suspected spies executed by the I.R.A. during the War of Independence in Galway were all Catholics; as were all seven suspected spies executed by the I.R.A. in Limerick. So even if it could be proved conclusively that the I.R.A. in Cork had engaged in a sectarian campaign against Protestants –the above figures show the dangers of assuming that the experience of one county during the war was reflective of the country as a whole.

It is interesting to note that the three civilians executed as suspected spies by the I.R.A. in Clare during the War of Independence, Martin Counihan, John Reilly and Patrick D’Arcy were all Catholics. This seems to rule out any possibility that the I.R.A. in Clare used the question of spies as a cloak for sectarian or ethnic cleansing against local Protestants. However this does not mean that Protestants in Clare were not suspected of being British spies. A list drawn up by the I.R.A.’s East Clare Brigade during the truce period lists fifty five suspected spies in the brigade area – six of the suspects listed were Protestant. [20]

A list drawn up by the I.R.A.’s East Clare Brigade during the truce period lists fifty five suspected spies in the brigade area – six of the suspects listed were Protestant. [20]

In August 1919 the I.R.A.’s East Clare Brigade, issued a proclamation against spies which warned:

‘Whereas – It has come to our notice that certain persons have been acting as spies for the enemy and giving information to enemy police … Any person found guilty of infringing this order will be tried by courts-martial and shot at sight.’ [21]

The fact that, in the first fourteen months after the East Clare Brigade issued the proclamation no suspected spies were executed by them, shows that despite the harsh and direct tone of the proclamation, the I.R.A.’s East Clare Brigade was not ‘trigger happy’ when it came to executing suspected spies regardless of their religion.

When theI.R.A in Whitegate suspected that the telephone in village’s post office was being used to send intelligence information about republican activities to theR.I.C. The local postmaster Richard Copithorne, a Protestant unionist from Cork was suspected. In response, two I.R.A. volunteers, Paddy Mc Inerny and Thomas Mc Namara were sent to raidthe post office. On 26 April 1921 they held up Copithorne at gunpoint and forced him dismantle the telephone’s mechanism. After Copithorne assured the two IRA Volunteers that the phone had been disabled they left.

The R.I.C. Auxiliaries stationed at Killaloe made repeated raids to try and capture Michael Brennan leader of the I.R.A.’s East Clare Brigade. Brennan had several close escapes from capture and it became obvious that the Auxiliaries were acting on accurate information supplied by a spy. The chief suspect appears to have been a Protestant R.I.C. pensioner named Blennerhassett. According to Brennan:

‘It was obvious that the Auxiliaries were well informed as to my local haunts and detailed investigation pointed to a local R.I.C. pensioner as a probable spy. The local volunteers were absolutely certain this man was a British Intelligence agent and they were insistent he should be shot. I had very little doubt that they were right, but as we had no direct proof I wouldn’t permit his execution, so they contented themselves with raiding his house and warning him. After the Truce I made the Auxiliary intelligence officer from Killaloe drunk in the Kilrush hotel and I learned from him that our suspect was in fact a spy. He went to Killaloe once a week for his pension and gave his reports to the R.I.C.’ [22]

The fact that Brennan refused to sanction the execution without ‘direct proof’ shows that he was fair and thorough in his investigation of suspected spies. The suspect’s religion was not mentioned by Brennan and does not appear to have been a factor in his treatment of the case.

The only Protestant civilian killed by the I.R.A. in Clare was Alan Cane Lendrum an ex-British Army Captain who had been appointed Resident Magistrate in Kilkee. On 22 September 1920 a group of I.R.A. Volunteers shot dead Lendrum at Caherfeenick railway crossing, near Doonbeg in West Clare. According to Liam Haugh O/C of the West Clare Brigades Active Service Unit the aim of the operation was to commandeer Lendrum’s car not to kill him.

‘The car was a Ford two seater and looked good in the eyes of some [I.R.A.] Volunteer officers. The tacit consent of the brigade commander was given for its seizure when opportunity favoured – with the understanding that its owner was not to be injured.’ [23]

When ambushed, Lendrum had drawn an automatic pistol to defend himself and was shot dead. There can be little doubt that the aim of the operation was not to kill Lendrum and that he was shot because he drew his gun when challenged. George Noblett, an R.I.C. District Inspector and personal friend of Lendrums, later commented:

‘They had orders to kidnap Lendrum not to shoot him. I am sure he resisted. Alan Lendrum was a man who would neverput his hands up and he always carried a small German automatic in those days. His resistance may well have cost him his life but any other action on his part would have been completely out of character.‘ [24]

Protestants and the British Reprisals

Generally, relations between the British forces and local Protestants and Unionists were good during the War of Independence however they occasionally suffered material and financial losses at the hands of the British forces. British born Black and Tans and soldiers cared little about the intricacies of Irish politics, knew even less, and regarded all Irishmen as potential Sinn Féiners.

Following the Rineen ambush 22 September 1920 in which six members of the R.I.C. were killed the British forces engaged in widespread reprisals, killing five people, destroying houses and businesses in Milltown Malbay, Lahinch and Liscannor. Though initially the reprisals were directed against suspected republicans, as the perpetrators began consuming looted alcohol their vengeance became less discriminating. Amongst the premises attacked were properties belonging to some Protestants including Thomas Blackwell in Lahinch and the Unionist politician H.V. Mcnamara in Ennistymon. Though it was beyond doubt that the R.I.C. and British soldiers were responsible for the reprisals, the R.I.C. County Inspectors report blamed the arson attacks on the mysterious ‘Anti-Sinn Fein Gang.’

On the 17March 1921 R.I.C. Constables Gray and Band, broke into the house of Lily Stewart and stole china ornaments valued at two pounds. The pair then proceeded to Henry Webster’s grocery shop where they broke a plate glass window valued at thirty pounds. Some unionists like Colonel O’ Callaghan Westropp were horrified by the reprisal killings and arson attacks carried out by the British forces. O Callaghan publicly condemned in speeches and letters British troops who were ‘running wild’ and how ‘Our men, that is the shame of it, were recruiting for Sinn Fein by their crimes and creating bitterness which is the main cause of a difficulty in making a permanent settlement.’ [25] Eventually the impact of these reprisals forced a Damascus style conversion on O’ Callaghan who changed from militant Unionism to supporting dominion Home Rule. O’ Callaghan paid for his condemnation on 2 January 1921 when the Black & Tans burned a hay barn and cattle shed on his property and pinned a notice to the door of his gamekeepers lodge reading:

‘Notice to O’Callaghan Westropp, commonly known as Mouse Trap. Our society has its eye on you. You are a double dealer and a twister. One more of your ruddy speeches or letters and you are doomed. There is no fool like an old fool, so beware. Be wise. Anti-Sinn Fein Gang.’ [26]

A similar incident happened in Killaloe in the wake of the murder Michael Egan and three captured I.R.A. Volunteers Martin Gildea, Alfred Rodgers and Michael Mc Mahon on 16th November 1920. R. C. Grey the retired English Civil servant mentioned above, wrote a pamphlet detailing and condemning the murders. This was published under the title ‘The Auxiliary Police’ by the ‘British Peace with Ireland Council’ in London. Grey who had waived his right to anonymity in the pamphlet was soon suffering intimidation from the R.I.C. and Auxiliaries stationed in Killaloe and eventually had to leave the area after receiving death threats.

A similar incident happened in Killaloe in the wake of the murder Michael Egan and three captured I.R.A. Volunteers Martin Gildea, Alfred Rodgers and Michael Mc Mahon on 16th November 1920. R. C. Grey the retired English Civil servant mentioned above, wrote a pamphlet detailing and condemning the murders. This was published under the title ‘The Auxiliary Police’ by the ‘British Peace with Ireland Council’ in London. Grey who had waived his right to anonymity in the pamphlet was soon suffering intimidation from the R.I.C. and Auxiliaries stationed in Killaloe and eventually had to leave the area after receiving death threats.

Outraged by the British policy of reprisals one Unionist landowner in Limerick, The O’ Connor Don, declared ‘Well tell Mr. Lloyd George, if the government don’t turn these damned Black and Tans out of the country we’ll soon all be damned republicans.’ [27]

In contrast some IRA leaders in Clare like Michael Brennan generally seemed to have been very lenient in their dealings with political opponents and local loyalists and knew the political effect that such incidents could cause. He later claimed;

‘I had always emphasised to Volunteers that armed action was only one arm in our fight for independence. I maintained that good propaganda was the other arm and the most important part of this was our own conduct. It was easy to behave well to our friends, but I argued that our critics and political opponents might become friends if we impressed them by our standards of conduct. The brigade adhered loyally to this and any tendency towards roughness against the public was checked at once. For example, when some visitors from East Limerick Brigade seized motor tyres from the Protestant rector of Kilkishen, a party followed them that night, recovered the tyres and returned them. The fact that, despite all their difficulties, Volunteers in East Clare behaved better than the forces of the crown had quite an effect on even old Unionists and it brought several of them to our side – e.g. Colonel O’Callaghan Westropp.’ [28]

House Burnings

One of the popular images of the War of Independence is of the I.R.A. burning the large country estate houses of Loyalists. Often this is interpreted as a ‘land grab’ so the republicans could gain control of these estates, sometimes these burnings are interpreted as a sectarian act of ethnic cleansing against southern Protestants. Because of this enduring popular image I have heard the republicans of Clare during the War of Independence referred to derisively as ‘paraffin Nationalists’. However the reasons why the I.R.A. burnt the houses of Clare Protestants during the War of Independence are far more complex than this.

The campaign of arson attacks in Ireland began as a British initiative to break the morale of the IRA and their civilian supporters in imitation of the British Army tactics used in the Boer War. However British reprisals often had the opposite effect not only strengthening the resolve of the IRA and their supporters, but also of driving moderate nationalists and civilians previously opposed to physical force republicanism to supporting the IRA. As British reprisals increased the I.R.A came under pressure to retaliate by burning the homes of Irish loyalists. Sean Hegearty commander of the Cork No.2 Brigade proposed that ‘A similar number of houses belonging to the active enemies of Ireland be destroyed’ in return. [29] According to Tom Barry leader of the 3rd West Cork Brigades Flying Column the policy of counter reprisals quickly became effective:

‘British burnings were suicidal and a bad policy, as the I.R.A. destroyed two large mansions for every farmhouse or cottage burned by the British. They instanced where following the destruction by the British of two small farmhouses worth less than a thousand pounds, four large houses worth twenty thousand pounds were destroyed by the I.R.A. This outcry had its effect, and although British burnings were never officially called off, they were slowed down considerably and even halted for a time.’ [30]

However the stately houses of loyalists were not solely burned on account of their owner’s politics, or as a means of counter-reprisal to stop British burnings. Large estates belonging to the supporters of British rule in Ireland were also burned by the I.R.A. to prevent them being used as temporary barracks by the British forces. As the I.R.A. continued to attack and destroy R.I.C. barracks during the war it became common for units of the British forces, in particular the British military and the R.I.C. Auxiliaries, to commandeer large stone buildings suitable for defense as temporary barracks. These buildings often included town halls, workhouses and courthouses in urban areas and large country estate houses in rural areas.

As most of these properties were owned by Protestants this gave British propagandists a chance to misrepresent the burning of the homes of Irish loyalists as part of a sectarian policy. To prevent this, I.R.A. Headquarters in Dublin issued General Order Number 26 which ordered that the burning of large estates could only take place if the owners were ‘the most active enemies of Ireland’. It emphasised that;

‘For the purposes of such reprisals no one shall be regarded as an enemy of Ireland, whether they be described locally as, Unionist, Orangemen, etc, except that they are anti-Irish in their outlook and actions.’ [31]

From May of 1921 sanction for all such operations were supposed to be obtained from the Brigade Commandant and Divisional Headquarters, who in turn had to inform I.R.A. General Headquarters in Dublin of the proposed action. Ideally in an established professional army these military orders would have been followed to the letter. However the I.R.A. was not an established professional army, it was a volunteer guerilla army and it was often difficult or impossible for local I.R.A. commanders to receive official approval for these attacks and some took the initiative without seeking or waiting for confirmation.

The I.R.A.’s campaign of arson attacks on loyalist houses in Clare did not begin until the last few months of the conflict in the Spring and Summer of 1921. On 19 February 1921 Mrs. A. Jane Gloster’s house at Kilrush was set on fire by the I.R.A. The fire did not destroy the building but did cause internal damage estimated at fifty pounds. The building was unoccupied at the time. The R.I.C. attributed the motive for the attack as being a military strategic one: ‘The Sinn Feiners thought that this building would be taken over by military or police’ [32]

This was not uncommon at the time, Beechlawn House at Newmarket-on-Fergus, Harbourhill House in Newquay, Richmond House at Corofin, and Newtown House in Ballyvaughan had all been used as R.I.C. Barracks. ‘The Square’, Kilrush owned by the Griffin family and Violet Hill House in Broadford had been used as barracks for the British Army. Not only did the British forces recognise the strategic value to the I.R.A. of burning these houses, in some cases they imitated it to deny facilities to the republicans. For example, Rathlaheen Cottage in Bunratty was burned down by the Black and Tans because it had been used by Cumann Na mBann. [33]

I.R.A. veteran Peader O’ Loughlin recalled that in Ennis very few of the town’s loyalist population were publicly expressed their support of the British forces:

‘While the Black and Tan war was raging, very few of the loyalist supporters carried their colours on their sleeves and of those who did, two families made themselves particularly objectionable to the I.R.A. One was Shaughnessy’s who kept a pub in Market Street,… At O’ Shaughnessy’s, though all the publicans were warned against serving drinks to the enemy forces, or at least letting them know that they were welcome, the Black and Tan members of the Ennis garrison were received with a ‘cead mile fáilte’, and also their friends and especially the ladies.’ [34]

Interestingly Miss Kate O’ Shaughnessy and her family who owned the pub were Catholics, proving that in the War of Independence the terms Loyalist and Protestant were not synonymous to the I.R.A.! On 16th of April, Peader O’ Loughlin and Volunteers from the 1st Battalion of the Mid Clare Brigade mounted an attack on off-duty British Army officers and Black & Tans drinking in the pub;

‘The I.R.A. in the town decided to attack the place and to kill as many as they could of the occupants. At about ten p.m. on the night of 16th April, 1921, a party of eight or nine men under Paddy Con Mc Mahon, and including Eamonn Baronn, Jim Quinn, Frank Butler, Joe Frawley, Jack D’Arcy and myself all armed with revolvers called at O’ Shaughnessy’s pub. The door was shut at the time, but was opened in answer to Paddy Cons knock, who stepped back a few paces after knocking. As soon as the door opened he hurled a mills grenade into the bar and the rest of us fired into the place with revolvers. Inside were Sergeant Rue, who was killed outright, Constable Vanerburgh, Mrs. Danagher and Miss O’ Shaughnessy, who were all wounded.’ [35]

In reprisal for the attack’ the shop of T.V. Honan, a leading member of the Ennis Sinn Féin club, was raided by British soldiers from the Royal Scots Regiment who removed the contents and furniture and set fire to them before demolishing the premises with explosives. Next they set fire to the home of Patrick Considine and burnt the Old Ground Hotel to the ground. The Clare Hotel was raided and all its furniture made into a bonfire and that night. Four days later the I.R.A. raided Mill View House, the property of Henry Mills a Protestant loyalist whom the I.R.A. alleged had actively assisted the British soldiers during the reprisals in Ennis, and burnt it to the ground as a warning to the British forces and local unionists against further reprisals. The damage to the house was estimated at six thousand pounds. In revenge for this attack an attempt was made to burn Westbourne House, residence of Dr. Fogarty Bishop of Killaloe who though often critical of the actions of the I.R.A. was associated with the moderate section of the Sinn Fein party and Dail Eireann. According to O’ Loughlin, Mill View House was burned as a ‘counter-reprisal’:

‘Mr. Mills was an Orangeman and a bigot. He detested the Sinn Féin movement and everyone belonging to it especially Dr. Fogarty, Bishop of Clare. It was suspected that he was involved in the attempted burning of the Bishops palace, while he openly assisted in the supervision of the destruction of T.V. Honan’s premises …’ [36]

On 18 May 1921 a failed attempt was made to burn down Kilmore house in Kilrush, only a small amount of damage was done to the building’s front door and windows. The R.I.C. stated that the motive ‘appears to be jealousy against Behan (the caretaker) as there were other candidates for the position.’ [37] The house had been owned by Francis W. Hickman an-unpopular figure locally whom Liam Haugh described as ‘a rack renting landlord.’ However he had died almost four years previously in 1917. Hickman’s son Thomas joined the R.I.C. Auxiliaries and gained a notorious reputation in the Longford / Roscommon area. In response to the burning of the family homes and businesses of known I.R.A. members by the R.I.C., the I.R.A. had begun arson attacks on the family homes of men who had joined the Black & Tans and the Auxiliaries in both Britain and Ireland – this is one possible reason that Kilmore house was targeted.

On 18 May 1921 a failed attempt was made to burn down Kilmore house in Kilrush, only a small amount of damage was done to the building’s front door and windows. The R.I.C. stated that the motive ‘appears to be jealousy against Behan (the caretaker) as there were other candidates for the position.’ [37] The house had been owned by Francis W. Hickman an-unpopular figure locally whom Liam Haugh described as ‘a rack renting landlord.’ However he had died almost four years previously in 1917. Hickman’s son Thomas joined the R.I.C. Auxiliaries and gained a notorious reputation in the Longford / Roscommon area. In response to the burning of the family homes and businesses of known I.R.A. members by the R.I.C., the I.R.A. had begun arson attacks on the family homes of men who had joined the Black & Tans and the Auxiliaries in both Britain and Ireland – this is one possible reason that Kilmore house was targeted.

On 21 March, 1920 Mr. Martin an Ulster Protestant who worked as a steward at Kilmore House shot at a group of I.R.A. Volunteers who were approaching the house to enforce a decision passed by the local Dail court against Hickman. The I.R.A. returned fire, and in the shoot-out one of the I.R.A. men accidentally shot and mortally wounded I.R.A. Volunteer Patrick Hassett. In the confusion that followed, the republicans wounded Martin and left assuming he was dead. Martin made a full recovery, resigned his position and returned to his home in the North. Following this, a party of British soldiers were stationed at Kilmore House. In August 1920 the soldiers were evacuated after the I.R.A. ambushed their supply lorry. Martin was replaced as steward of Kilmore by Richard Behan.

There are a number of possible motives why Kilmore was burnt; the family’s unpopularity with their tenants in previous years, jealousy of Behan as cited by the R.I.C., the use of the house by the British Army, or Thomas Hickman’s membership of the Auxiliaries. On 5 July 1921, Hazelwood House in Quin, another property belonging to the Hickman family, was burned down by the I.R.A. Hazelwood and its contents were valued at one hundred thousand pounds.

On 19 May 1921 the vacated temporary R.I.C. barracks at Doolin [possibly located in Doolin House] was burned down by the I.R.A. The property used for the barracks belonged to H.V. Macnamara. In June 1921 the R.I.C. reported that;

‘The residences of five country gentlemen were destroyed by fire during the month. These gentlemen are all loyalists.’ It further stated that ‘Practically all the above crimes were political the only exceptions being a few cases of larceny.’ [38]

‘The residences of five country gentlemen were destroyed by fire during the month. These gentlemen are all loyalists.’ It further stated that ‘Practically all the above crimes were political the only exceptions being a few cases of larceny.’

Conclusion

Clare was one of the most militant and active counties in terms republican attacks during in the War of Independence, however the pattern and development of the war in Clare does not suit the newly proposed sectarian thesis promoted By Hart, Harris, Myers et al. No Clare Protestants were executed by the I.R.A. as suspected spies. Only one Protestant civilian was killed by the I.R.A. in Clare, this appears not to have been premeditated and the circumstances of this incident do not imply sectarianism. Finally there were legitimate non-sectarian political and military reasons why the I.R.A. burned houses and property belonging to Protestants during the final phase of the war of Independence. Hart’s claim that ‘sectarianism was embedded in the Irish revolution, north and south’ certainly cannot be justified or supported by the nature of I.R.A.’s campaign in Clare during the War of Independence. It seems clear that whilst the conflict in some of the most north-eastern counties had a definite sectarian and tribal element, in the vast majority of other counties throughout Ireland it did not.

The proclamation of the Irish Republic in 1916 which embodied the ideals that Sinn Fein and the I.R.A. claimed to be fighting for during the War of Independence had stressed that the Republic guaranteed ‘equal civil and religious liberty to all its citizens regardless of the differences carefully fostered by an alien government that have divided a minority from the majority in the past.’ De Valera Sinn Fein T.D. for East Clare and the President of the Irish Republic on a tour of the United States in 1920 declared.

‘It is pretended that this question is a religious question. I deny it. There is no question of religious differences dividing us in Ireland’ [39]

De Valera was accompanied on his speaking tour for a period in 1920 by Rev J.A.H. Irwin, the Presbyterian Minister of Killead, Co Antrim who supported de Valera’s claims that there were no religious differences in Ireland

‘As a matter of fact our divisions in Ireland are like the divisions in any civilised country in the world: political and economic and not religious. … It suit’s the politicians to say that the Irish question is a religious question but that game is pretty well played out.’ [40]

The the Protestant Bishop of Killaloe who presided over a meeting of the General Synod of the Church of Ireland on 12 May 1922 issued a statement seemingly in agreement with de Valera and Reverend Irwin’s comments which stated

‘…hostility to Protestants by reason of their religion has been almost, if not wholly, unknown in the twenty six counties in which Protestants are in the minority.’ [41]

_____________________________

Footnotes

1.Peter Hart , ‘The Protestant Experience of Revolution in Southern Ireland ‘ in ‘Unionism in Modern Ireland’, ed. Richard English Pages 89-94

2. Thomas Shaloo Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1075

3. Clare Champion September 30th 1911

4. Clare Champion October 14th 1911

5. Clare Champion November 4th 1911

6. Clare Champion November 4th 1911

7. Clare Champion November 4th 1911

8. The Memoirs Of John M. Regan A Catholic Officer In The RIC And RUC 1909 – 48. Dublin 2007 Pg. 69

9. Irish News quoted in the Clare Champion January 24 1914.

10. A Journey in Ireland 1921 Wilfrid Ewart Dublin 2009 Page 80

11 C.D. 227/16/19 ‘The Auxiliary Police’ by R.G. Grey Published by the ‘Peace With Ireland Council’, London 1920

12 The Memoirs Of John M. Regan, A Catholic Officer In The RIC And RUC 1909 -48. Dublin 2007 Pg. 78

13. Note: The regimental chronicle does state that Loyalists – a political and not religious term since the O Shaughnessy’s of Ennis who the I.R.A. described as being ‘Loyalists’ were Catholics – were ‘… in constant danger of seeing their houses burned and their motor cars purloined…’ however there were military reasons for such actions which were recognised in some cases by the British forces. It does not state that there was religious or sectarian persecution of Protestants.

14. Coolacrease. The true story of the Pearson executions – an incident in the Irish War of Independence. Edited by Philip O Connor. Page 178

15. County Inspectors Report July 1920

16. Emphasis in original. Military Archives. Captured documents collection Lot 24/4

17. County Inspectors Report March 1921

18. County Inspectors Report May 1921

19. Peter Hart , ‘The Protestant Experience of Revolution in Southern Ireland ‘ in ‘Unionism in Modern Ireland’, ed. Richard English Pages 89-90

20. P7a/15 Mulcahy Papers

21. Anti-Spy Proclamation Clare Museum

22. Michael Brennan, ‘The War In Clare’, Four Courts Press 1980

23. Liam Haugh Bureau of Military History Witness Statement

24. Emphasis in original. Letter George Noblett to Rex Taylor. Private Collection

25. O Callaghan to T. Edwards 26 Oct 1920

26. O Callaghan Westropp Letterbooks Quoted in Politics and Irish Life Cork1998 David Fitzpatrick Pg. 69

27. The Black and Tans. Richard Bennett

28 Michael Brennan, ‘The War In Clare’, Four Courts Press 1980 Page 85

29. U.C.D. P7 / A/18: Mulcahy to Brugha, 14 May 1921.

30. Tom Barry ‘Guerilla Days in Ireland.’ Anvil Books 1981 pages 116 -117

31. UCD P7 / A / 45 General Order 26

32. County Inspectors report March 1921

33. Houses of Clare by Hugh W.L. Weir Ballinakella Press, Clare 1986. Page 224

34. Peader O Loughlin Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 985

35. Peader O Loughlin Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 985

36. Peader O Loughlin Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 985

37. County Inspectors report May 1921.

38. County Inspectors report June 1921

39. De Valera in America, By Dave Hannigan. Page 57 O Brien Press 2008

40. C.D. 1/5/11 Sean Collins Collection, Irish Military Archives Cathal Brugha Barracks. Pamphlet entitled An Ulster Republican by Rev J.A.H. Irwin,

41. Quoted in Meda Ryan, ‘Tom Barry. I.R.A. Freedom Fighter, Mercier Press, Cork 2005 Page 215