Today in Irish History – Assassination of Sean Hales, December 7 1922

John Dorney looks at the savage bout of assassinations and executions in December 1922 during the Irish Civil War.

On December 6th, 1922, the Irish Free State, provisionally set up under the Anglo-Irish Treaty in January, was formally established by an Act of the British Parliament. Eleven days later the last 6,000 British troops in Dublin were shipped back to Britain.

The Irish, however, were still fighting a bitter civil war over the Treaty. Since November 17, the Free State had executed eight Republican prisoners under emergency legislation known as the Public Safety Bill. One of the executed was Erskine Childers, secretary of the team that had negotiated the Treaty.

The following day, December 7, TDs Sean Hales of Cork and Padraig O Maile of Mayo emerged from their lunch at a hotel on Ormonde Quay, along Dublin’s river Liffey, ten minute’s walk from the still-ruined Four Courts (destroyed in a battle at the outbreak of the Civil War in July), for the short drive to the Dail in Leinster House.

Both had been active in Sinn Fein and the IRA in the struggle against the British, but had supported the Treaty. Hales had a brother, Tom, in hills of west Cork fighting with the Anti-Treaty IRA.

As they were getting into the car that would drive them to parliament, two gunmen opened fire on them, killing Hales and severely wounding O Maile, before disappearing into the backstreets behind the Quays. It was revenge for the Free State’s executions.

A British armoured car was passing by and its soldiers, in what may have been the last actions ever by British soldiers in Dublin, fired some fleeting shots after the assassins as they ran in the direction of Capel Street.[1]

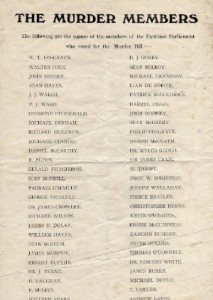

Liam Lynch, Anti-Treaty IRA Chief of Staff, had ordered the killing of any TD who had voted for the “Murder Bill” and also threatened hostile judges and newspaper editors.

Frank Henderson, head of the IRA Dublin Brigade had, apparently, ordered the killing only of O Maille, the Leas Cean Comhairle, or Deputy Speaker of the Dail, and was dismayed that Hales had been killed. For 16 years afterwards he had his son, a priest, say a Mass for Hales.[2]

The actual killer, the playwright Ulick O’Connor was told in 1985, by Sean Caffrey, an ex-IRA Intelligence officer, was Owen Donnelly, from Glasnevin, “a rather girlish-looking, fair-haired fellow who had been a very good scholar in O’Connell Schools.”

“Who ordered him to do it?” I asked.

“No one gave him an order,” he said. “At that time the general orders issued by Liam Lynch were for anybody to shoot TDs or Senators if they could.”

He was in the main room of the Intelligence Centre when Donnelly came in shortly after the killing, on the afternoon of December 7, 1922. I asked Caffrey what was his reaction when he heard Sean Hales had been killed.

“I was delighted,” he said and then gave a little chuckle, as if reminiscing over something which he particularly enjoyed.” Donnelly was carrying on the fight,” he said. “There are no rules in war. The winner dictates the rules.” [3]

A brutal exercise in reprisals had begun.

The Cabinet met in an emergency session and decided, after an all-night debate, on retaliatory executions of four Republican leaders captured in the Four Courts back in July – Liam Mellows, Rory O’Connor, Dick Barret and Joe McKelvey. The executions were no more and no less than a reprisal killing for the death of Sean Hales.

The four had been captured months before the Government had even proposed its emergency legislation in September 1922.

They received the following typed notice;

“You ________ are hereby notified that, being a person taken in arms against the government, you will be executed as a reprisal for the assassination of Brigadier Sean Hales TD in Dublin on December 7th, on his way to a meeting of Dail Eireann and as a solemn warning to those associated with you who are engaged in a conspiracy of assassination against the representatives of the Irish people”.[4]

The four were shot in Mountjoy Prison within hours of the Cabinet’s decision.

Shocked Labour Party TDs in the Dail expressed outrage at the government’s action, Tom Johnston: “It was a horrible, dastardly thing, the assassination of Sean Hales…but this was murder most foul, bloody and unnatural. The four men in Mountjoy have been in your charge for five months. You were charged with the care of those men; that was your duty as guardians of the law.” [5]

Defending the executions, from charges of personal vengeance,Minister Kevin O’Higgins exclaimed, “Personal Spite! Great Heavens! Vindictiveness! One of these men was a friend of mine![6]

Rory O’Connor had not only been a friend of O’Higgins, but actually the best man at his wedding only the year before.

O’Higgins had the reputation as the hard man of the cabinet, but he was the last member to give his approval for the execution of his friend. He never expressed regret over the judicial killings however, defending them as a grim necessity. Taunted by Republicans in 1925 over the Civil War’s 77 executions, he responded, “I stand by the 77 executions and 777 more if necessary”.[7]

It is in no way to defend the executions to suggest that they did indeed terrorise the Anti-Treatyites sufficiently to stop them embarking on full scale assassination campaign of TDs.

Frank Henderson remembered, “I could have shot [TDs] Eamon Duggan and Fionan Lynch for they went home drunk every night, but I left them alone. Sean McGarry was often drunk in Amiens street and the boys [IRA men] wanted to shoot him but I wouldn’t let them. I think the execution of Rory O’Connor and the others may have stopped our shooting. It was very hard to get men to do the shooting and I don’t think they’d have done any more shooting”.[8]

See also: Podcast, Assassination and Execution: Sean Hales and the Mountjoy executions, December 1922.

[1]Irish Times, December 16, 1922

[2] Frank Henderson, Michael Hopkinson, Frank Henderson’s Easter Rising, p 7

[3]Ulick O’Connor, The Truth behind the Murder of Sean Hales, Sunday Independent, February 17, 2002.

[4] Maryann Gialanella Valiulis, Portrait of a Revolutionary, General Richard Mulcahy and the founding of the Irish Free State, p181

[5] Dail Debates 8th December 1922, http://debates.oireachtas.ie/dail/1922/12/08/00007.asp

[6] Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, The Irish Civil War, p191

[7] Anne Dolan, Commemorating the Irish Civil War, p4

[8] Frank Henderson’s Easter Rising, p7