Today in Irish History – The Upton Ambush, February 15 1921.

On this day, in west Cork, in 1921, at least eleven people were killed in a vicious ten-minute firefight at Upton train station during the Irish War of Independence. By John Dorney.

At 10:18, on February 15, 1921, a station master at Upton station, a small isolated red-brick building on the line between Cork city and Bandon, was approached by a person he later described as “a stranger”, who asked him when the next train from Cork was in.

The railway employee told him that a goods train was due in about ten minutes. “What about the passenger train?”, the man asked. That was due shortly after, he was told.

The man went away, “satisfied”, but minutes later 14 armed men descended on the station, tied up the station master and made ready to fire on the incoming train. Some made a “strongpoint” of corn bags, while others occupied the station house itself.[1]

An improvised ambush

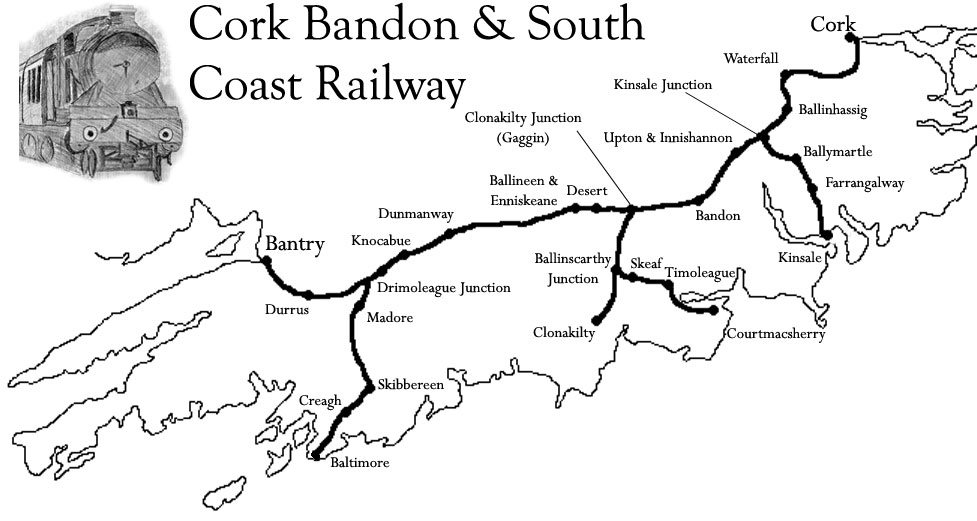

The guerrillas were a scratch force assembled at short notice by Charlie Hurley, the commander of the IRA Third Cork Brigade. The Brigade’s Flying column – its fulltime guerrilla unit, led by Tom Barry, was elsewhere, returning from an attempt to blow up the RIC barracks at Drimoleague.

Hurley had heard from the IRA in Cork city that 20 British soldiers from the Essex Regiment, would be travelling to Bandon in one carriage and hastily mobilised men from the local IRA companies to attack it. Seven had rifles, the rest were armed only with handguns.[2]

The guerrillas were a scratch force assembled at short notice – the Brigade’s flying column was elsewhere

Despite the improvised nature of the attack, Hurley had reason to be optimistic. Just five days earlier, he had led a similar ambush of a train at Drishanbeg, killing one soldier and wounding five. What he did not know was that, along with the original 20 soldiers, another 50 had boarded at Kinsale junction.[3] The IRA had posted two scouts at Kinsale Junction, but although one of them raced by bicycle to tell the ambushers of the extra troops on board, he arrived too late.

On the train’s four carriages, as well as the 70 odd British soldiers, were many civilians, including a large number of “commercial travellers”, or wholesalers. One, for instance, was C.P. Johnston, aged 50, originally of Cork but resident in Rathmines, Dublin. Another was the ticket collector, Richard Arthurs (45), of St Lukes Road, Cork.[4] Despite the ongoing guerrilla warfare, normal life for the most part went on and the passengers could not have expected what happened next.

A storm of fire

When the train pulled into Upton station, a storm of fire broke out from the ambushers, ripped into the carriages, smashing through the windows and into soldier and civilian alike. Reports speak of, “a shower of bullets”, “sweeping” and “riddling” the train. Arthurs, the ticket collector, died instantly, as did two commercial travellers, James Byrne of Dublin and John Spiers of Cork. CP Johnston was hit in the leg and lay bleeding to death in the guard van.

When the British troops recovered from the initial shock, they returned fire on the outnumbered IRA fighters. One of them, according to the inquest, worked his way to the rear of the Volunteers’ position and killed two of the IRA men.

The bodies of the two Volunteers had to be left at the scene, as the ambush party made a disorderly retreat across country. They carried with them several wounded. One, Pat O’Sullivan, was shot in the stomach and was taken in at a local farmhouse. Despite being smuggled to a hospital in Cork city by horse and trap, he died of his injuries a few days later.

Another man, Dan O’Mahoney, recovered in the short term but died some years later died from his wounds. Charlie Hurley himself was shot in the face but survived.[5]

The train was a scene of carnage – eight civilians were killed and six wounded along with six British soldiers. On the station, two IRA men lay dead, another was a carried away by his comrades.

The train itself was scene of carnage. The British troops found six dead civilians in the carriages and eight wounded, of whom two died later.[6] Among the dead was Arthurs, the ticket collector, three commercial travellers, and a woman, May Hail. The British casualties were not given at the inquest, but reports at the time said that six were wounded, three seriously.[7] The IRA suspected that several were killed.

The firing had lasted just ten minutes.

The British had suspended Coroners Courts in Cork and replaced them with, “Military Courts of Inquiry”. It found that the civilians had been, “wilfully murdered by persons unknown” but that the two dead IRA men they knew about, “died from wounds inflicted by the military in justifiable self-defence”.[8]

Civilian casualties

Both the British Army and the IRA claimed that they had tried not to put civilians in harm’s way, but neither claim is especially convincing.

The British claimed that no civilians were allowed in the same carriages as soldiers, but this is disproved by the Irish Times report of the fatal wounding of CP, Johnston, who was, “in a van with some soldiers and a civilian, John Sisk, the van was riddled with bullets”.[9] Clearly soldiers and civilians were mingled throughout the train.

Both the British and the IRA claimed that had tried to keep civilians out of harm’s way. Neither was very convincing

The IRA for their part claimed that they mistakenly thought the British troops were concentrated in two central carriages of the train and that they fired only on these. But again, press reports and the sheer amount of casualties, contradict this. According to the New York Times report, “a shower of bullets was rained on the train, practically every compartment being swept”.[10] According to the Irish Times, “the whole train was riddled”.[11]

It doesn’t seem as if Hurley and his men thought too much about civilian casualties when they opened fire.

Context

The Upton ambush was only possible because as of December 1920, railway workers, under pressure of sacking, had called off a strike on carrying British troops which had been declared in May 1920. So in one way, what happened at Upton reflects a shift in late 1920 and early 1921, from mass civil disobediance among Irish nationalists, combined with some armed actions, to a much-more-lethal situation of all-out guerrilla warfare.

County Cork was the storm centre of the War of Independence. A total of 523 people were killed there and another 513 wounded, or between 25-35% of the total casualties of the war.[12] And February and March 1921, was the most intense period.

Cork was the storm-centre of the War of Independence and February and March 1921 were the two most intense months.

Martial law was declared in Cork and the county was flooded with British regulars, Auxiliaries and RIC. At the same time, the spring of 1921 was the high point of the IRA flying columns’ actions.

Because of this, this two-month period saw the highest losses on both sides during the war. Of the 33 members of the Third Cork Brigade killed from August 1920- July 1921, 18 were killed between January 17 and March 22, 1921.

Of these, eleven were killed between 4 February and 16 February, including the three at Upton. One was killed in an accidental shooting, of the remaining seven, four were arrested and then shot by British troops, three more were assassinated in their beds.[13]

Elsewhere in Cork, things were equally bloody. On the same day as the Upton ambush, five IRA Volunteers were killed at Mourne Abbey – an informer had given away their ambush position, two more were captured and later executed. Just five days later another 12 IRA men were killed, many after surrendering, after being trapped in a house at Clonmult, north Cork.[14]

The IRA also hit British patrols hard at ambushes at Coolavig (25 February) and Clonbanin (5 March) – killing seven. In Cork city on February 29, in retaliation for the execution of six of their men, the IRA shot and killed 6 off duty British soldiers and wounded 5 more.

The striking thing about the Upton attack was the high number of civilian casualties. This was relatively unusual, since most IRA ambushes took place in the countryside; but where they operated among the civilian population it did happen.

In an attack on a train at Headford junction in Kerry a month later, three civilians were killed, along with ten British soldiers. In the spring of 1921, 46 bystanders were killed in IRA attacks on Crown forces in Dublin.[15] The IRA, in other words, while they did not usually intend to cause civilian deaths, was not particularly careful to avoid them either.

Aftermath

An IRA man, named in the press as, “Patrick Coakley, alias John Buckley” and described by the British military, as “a hatless and excited man”, was arrested with a rifle at the scene of the Upton ambush[16].

Charlie Hurley claimed that Coakley, “turned up with a rifle that day, hid in a house and never fired a shot”. After his arrest, a sympathetic RIC sergeant told the IRA that Coakley had, “given the game away”, under interrogation. He later claimed that he had talked, “under the influence of drugs”. The IRA sentenced him to death as a spy, but commuted the sentence to “exile for life”.[17]

As he was imprisoned, for, “levying war against the King”[18] his IRA court martial must have happened after the Truce of July 11. Whether he was an actual spy, or just a frightened young man, drugged and threatened with torture (as was common among IRA detainees) we don’t know.

Hurley may have been trying to deflect criticism from himself. According to Tom Barry, “He mourned deeply for his dead comrades at Upton and for the dead civilians whom he did not know, until he followed them a month later, riddled by British bullets”.[19]

The information Coakley gave to the British very nearly led to the surrounding and annihilation of the Third Cork Brigade’s flying column a month later (March 19), at Crossbarry. In the ensuing fighting, Charlie Hurley was killed along with three other IRA men. Tom Barry managed to extricate the rest of the column, in the process killing ten British soldiers.[20]

Crossbarry has been called, “a landmark success”, for the IRA and even (hyperbolically), “The Decisive Battle of the War of Independence”. What is less remarked on is that it was also the last major engagement between a IRA flying column and British forces in Cork before the July 11 truce. IRA ammuniton was very low and more and more British troops were flooding in to the county, making “stand-up fights” of this kind more and more difficult to pull off.

The last major operation of the Third Cork Brigade was a successful attack and destruction of Rosscarbery RIC barracks on March 30. For the remaining three months they spent most of their time avoiding “sweeps” of several thousand British troops across the countryside.

Memory

Two weeks after the Upton ambush, in a letter to the Irish Times, the Irish Commercial Travellers Federation wrote, “three respected members of ours were shot dead at Upton…we feel compelled to protest at conditions prevailing…as a non-political association, we refrain from offering opinions as to the causes…but we are convinced that unless the whole question is approached with goodwill and in a businesslike way, the results will be disastrous in the extreme”.[21]

The Times itself, at that time a unionist paper, headlined the escalation of the war in the southern county as “Cork’s Dreadful Record”.

While there was much support for the IRA in the Irish population in 1921, there was also ambivilence and opposition. What is remarkable is how quickly a consensus view of the war and of the Upton ambush in particular, emerged after the founding of the Irish Free State in 1922.

In an obituary for Sean Hales, assassinated by the anti-Treaty IRA in December 1922 in the Civil War, the Irish Times wrote “in hostilities against the British…he kept the Volunteers together in south and west Cork. He was involved in many ambushes, including …Upton, Kilmichael and Crossbarry.”[22]

In fact Hales was not present at the Upton ambush, (or at Kilmichael, though he did fight at Crossbarry). The striking thing about the Irish Times obituary however, is that just under two years after the event, what happened at Upton had been transformed into a glorious thing to have been involved in. That the Irish Times had condemned the ambush at the time as ‘murder’ was already forgotten.

Another three IRA men died at Upton on October 4th, 1922 in the Civil War – republican sources say they were “murdered at  Upton”.[23] The Irish Times barely even reported on their deaths. They had died on the wrong side, in the wrong war, and on the losing side.

Upton”.[23] The Irish Times barely even reported on their deaths. They had died on the wrong side, in the wrong war, and on the losing side.

In 1968, a memorial was opened at the site of the 1921 Upton ambush, listing the three IRA Volunteers killed there. No mention was made of the eight civilians who had also died in the crossfire.

Also in the 1960s, a maudlin dance hall ballad was written about the Upton ambush. The chorus goes;

Let the moon shine out tonight along the valley,

Where those lads who fought for freedom now are lain.

May they rest in peace those men who died for Ireland,

And who fell at Upton woods for Sinn Fein.

And the fighting is presented as a Custer-like last stand;

The warning cry rang out now: “Fix your bayonets”,

And right gallantly they fixed them for the fray,

Gallantly they fought and died for Ireland,

Around the lonely woods at Upton far away.

Even allowing for artistic license, the reality was not even close to that to which Irish couples swayed demurely in the dance halls of the 1960s.

What Ireland forgot in this era was that the War of Independence was in fact a savage and ruthless business, What it remembered was semi-imaginary but unifying myth of noble struggle and self-sacrifice

What Ireland forgot in this era was that the War of Independence was in fact a savage and ruthless business, that many were appalled by the IRA’s methods and that many of those who fought in the IRA ended up being locked up or killed by the state they helped create. What it remembered was semi-imaginary but unifying myth of noble struggle and self-sacrifice.

On the other side, the British public, by and large, never knew in the first place that their troops had systematically tortured and killed prisoners in Ireland and thus had no need to forget.

And even that is not quite the end of the story. After the start of the armed conflict in Northern Ireland in the late 1960s, songs like, “The Men who died at Upton”, were dropped from radio play on the Irish national broadcaster. With the interests of the state threatened by republican paramilitaries, it was no longer politic to play up the state’s violent origins.

Today perhaps enough time has passed and wounds have healed enough from conflicts both in the 1920s and more recently, for us to look at the reality of those times, both good and bad, in the face.

References

[1] Irish Times report on Military Inquest to ambush, March 31, 1921

[2] Tom Barry, Guerrilla Days in Ireland (1981), p94

[3] Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence (2004), p112.

[4] Irish Times, February 21, 1921

[5] For the British perspective, Irish Times March 31, 1921. For the IRA, Barry, Guerrilla Days, p94 Strangely enough the British inquest named the two dead IRA fighters as William O’Donoghue and Sean Hegarty, but the Third Cork Brigade’s own roll of honour lists their dead at Upton as John Phelan, Patrick O’Sullivan and Batt Falvey with Daniel O’Mahoney mortally wounded. For the account of the deaths of O’Sullivan and O’MAhony, see Frank Neville BMH statement, WS 443

[6] The eight civilians killed at Upton were; John Spiers, Thomas Perrot, James Byrne, CP Johnston, William Finn, May Hail, John Sisk and Richard Arthur, Irish Times March 31, 1921

[7] New York Times, February 16, 1921

[8] Irish Times, March 31, 1921

[9] Irish Times February 21, 1921

[10] New York Times, February 16, 1921

[11] Irish Times, February 21, 1921

[12] Peter Hart, IRA and its Enemies (1999), p87

[13] Barry, Guerrilla Days, p96-98

[14] Hopkinson, p111

[15] Tom Doyle, the Civil War in Kerry, (2007) p43

[16] Irish Times March 31, 1921

[17] Meda Ryan, Tom Barry, IRA Freedom Fighter (2003), p93

[18] Irish Times, March 22, 1921

[19] Barry, p95

[20] Hopkinson p111

[21] Irish Times, 28 February 1921.

[22] Irish Times, December 16, 1922

[23] Wolfe Tone Annual 1961, p25, They were Patrick Pearse, Donal O’Sullivan and Michael Hayes.