The Munster Plantation and the MacCarthys, 1583-1597

The Munster Plantation – the English land confiscation and colonisation – hit the province after the Desmond Rebellions of the 1570s and 80 – here, in the first part of a series of articles on the period, John Dorney looks at the fortunes of the MacCarthy clans in the face of it.

The Munster Plantation – the English land confiscation and colonisation – hit the province after the Desmond Rebellions of the 1570s and 80 – here, in the first part of a series of articles on the period, John Dorney looks at the fortunes of the MacCarthy clans in the face of it.

The Munster plantation was the product of the Second Desmond Rebellion, which broke out in 1579 and raged until 1583. It was a revolt by Gerald Fitzgerald, the Earl of Desmond against the English state’s interference in his territory but also, to different participants, a Catholic crusade assisted by Papal troops and a rebellion by elements of Gaelic society, threatened by the advancing English administration.

After four years, the war was brought to an exhausted end by the relentless use of scorched earth tactics of the English and their local allies. Led by the Lord Deputy Grey and the Earl of Ormonde they destroyed arable land and seized and killed livestock.

In November 1583, Gerald Fitzgerald, the Earl of Desmond, was hunted down and killed in the Slieve Mish mountains in Kerry. His head was sent to Queen Elizabeth. His body was triumphantly displayed on the walls of Cork.[1]

A devastated province

The Desmond wars smashed the Fitzgerald or Geraldine dynasty which had dominated Munster for centuries. The former Fitzgerald lands were confiscated en masse. Similarly harsh action was taken against their allies – the lord of the Barry family, for instance, was kept in the Tower of London until his death, and his heir was ordered to pay a (then huge) annual fine of £50[2].

More important for the ordinary people of Munster than a change of landowners was the devastation of much of the province. The Provincial President, Warham St Leger reported in April 1582 that up to 30,000 people had died of famine as a result of the scorched-earth tactics that had been used.

Munster was devastated by the Desmond Rebellion up to 30,000 died of famine in 1582

‘Munster’, he wrote, was, ‘nearly unpeopled by the murders done by the rebels and the killings by the soldiers’[3] Plague also broke out in Cork city, where the country people fled to avoid the fighting and it is estimated that by 1589, one third of the province’s population had died. [4]

Edmund Spencer, poet and colonist, spoke of ‘a most populous and plentiful country suddenly left void of man or beast’[5] . The Gaelic Annals of the Four Masters, for their part, recalled, “At this period it was commonly said, that the lowing of a cow, or the whistle of the ploughboy, could scarcely be heard from Dun-Caoin to Cashel in Munster”.[6]

Fertile places such as county Limerick recovered relatively quickly. By 1587, the Solicitor General Roger Wilbraham reported that ‘this is a most plentiful year of corn…[there are] five times a many Irish inhabiting in the county of Limerick as were within these two years’. He urged the settling of more English planters there before all the land was re-occupied by the Irish[7].

In mountainous south Munster recovery took longer. William Herbert reported the following year that, ‘this province’s waste and desolate parts…[are] by reason of the calamities of the late wars, void of people to manure and occupy the same’[8].

In 1588, the Provincial President, Warhame St Leger reported of MacCarthy Mor’s lands that, ‘The most part of his land is waste and uninhabited, which hath partly grown by the calamities of the late wars, partly by the exactions that he hath used on his tenants’[9].

Plantation

In the wake of Desmond wars, the English were determined to break up those Irish lordships whose command of thousands of dependents or ‘followers’ and hundreds of armed retainers made them an unacceptable security risk to the expanding English state in Ireland.

In the wake of Desmond wars, the English were determined to break up those Irish lordships whose command of thousands of dependents or ‘followers’ and hundreds of armed retainers made them an unacceptable security risk to the expanding English state in Ireland.

The Lord Deputy Henry Sidney, for example, in 1583, advised “the dissipation of the great lordships; if among the English the better, if not, yet that they be dissipated”[10]. In the future, English policy in Munster would be dominated by the desire to dismantle the Gaelic Irish lordships.

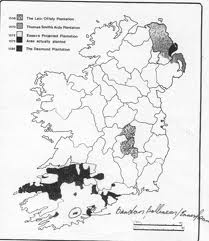

“If among the English the better”, Sidney had written. Within the devastated and depopulated lands of the Fitzgeralds, just such a Plantation was instituted. The project was put in the hands of Undertakers – in modern terms, a cross between colonists and land investors – responsible for introducing English tenants into their seignories of 400-1200 acres and creating compact, defensible settlements.[11]

In June 1584, a commission surveyed southwest Munster, mapping out the lands belonging to a swathe of Irish lords associated with the rebellion, which were then granted to a small group of wealthy English .Undertakers.[12]

Colonisation or civilising mission?

The Munster Plantation had been mapped out using clear calculated lines and detailed advice on how to effect an orderly English settlement. The reality, by contrast – a rush by the Undertakers to appropriate land and to fill it with tenants recruited in England and Wales – was chaotic.

Popham, the Attorney General for Ireland, for instance, imported 70 tenants from Somersetshire, only to find that that the land had already been settled by another undertaker and he was obliged to return them home at his own expense[13].

It was hoped that the settlement would attract in the region of 15,000 colonists, but in 1589 by Attorney Generals Popham and Phyton were dismayed to report that the undertakers had imported only in the region of 700 English tenants between them[14].

The plantation was supposed to settle 15,000 colonists on some 500,000 confiscated acres but the actual number of settlers was only some 700.

It has been suggested that each tenant was the head of a household, and that he therefore represents 4-5 other people[15], which would put the English population in Munster at nearer 3-4000, but it was still substantially below what the planners had hoped for.

While Tudor policy in Ireland might look to modern eyes like straighforward conquest and colonisation by one group over another, the English themselves did not see it like that. Rather, they viewed the plantation as a benevolent act, whereby the “barbarous”, militarised Irish lordships would be replaced by peaceful, law-governed English landholding system.

The native lords, whether descended from Anglo-Normans or Gaelic Irish, could remain, but as landlords, not military chieftains. Another aim, still secondary at this stage, was to import the Protestant reformation into Ireland.

So the plantation was conceived not only as punitive measure, or a tactic to create a loyal English bridgehead in Munster, but also as an example, to ‘civilise’ the province. William Herbert, an undertaker who received lands in Kerry, voiced the hope that the by the planters, “good example, direction and industry, both the true religion, sincere justice and perfect civility might by planted”[16].

What this vision ran up against was the reality that one class of militarised landowners was being violently replaced by another, foreign, one. For those undertakers such as Herbert, who genuinely subscribed to the idea of a “reformation” in Ireland in both religion and society, the reality of the plantation was somewhat disillusioning. He described his fellow undertakers as, ‘lewd, indiscreet and insufficient men’[17] who, ‘ measure conscience by commodity and law by lust’.[18]

Notions of societal ‘reform’ ran up against the reality that one militarised landowning class was being replaced by another

He also complained of the depredations of English soldiers, who were maintained by the undertakers for their defence, ‘Gentlemen [are] being stroken [robbed] evil entreated and abused, outrageous words and violent deeds rife and common towards the Irish of all sorts; taking of meat and drink and money for themselves…it seemeth to me the ready way to make the Irish weary of their loyalty and their lives’[19].

Herbert came from a landowning family in the marchers, or border country, of Wales and had more understanding than most undertakers of what it took to reconcile a culturally distinct populace to Crown control. He urged the impartial jurisdiction of Common Law ‘without respect of nations…to reduce these parts to a love of justice and government’[20] and the use of Irish language to instruct the natives in ‘civility’ and the Protestant religion; ‘I have taught them the truth in their natural tongue…which in a strange tongue would be to them altogether unprofitable’ [21].

In practice, though, Common Law, the pillar of what the English percieved as their superior civilisation, tended to be set aside when it got in the way of land confiscation. Roger Wilbraham, the Solicitor General, reported in 1587 that he had suspended judicial hearings on land confiscation because, ‘the Irishry have practised many fraudulent shifts for preserving their lands from forfeiture…and albeit their evidence be fair and very law-like without exception, yet because fraud is secret and seldom found for her Majesty by jury, we have put undertakers in possession’[22].

Other undertakers such as Edward Denny, took a dim view of Herbert’s soft, Welsh, attitudes towards the Irish; ‘to gain himself glory and thanks among the Irish, [he] pleads for them more than is fit, let us not suffer for his humour. A Welsh humour and a fat conceit hath led him foolishly’[23] For Denny, only complete conquest of the Irish would pacify the province, ‘[they] should not be left wealthy, populous or weaponed till they are first brought to God and obedience to the laws’ and, ‘no persuasion will ever win the Irish to God and her Majesty, but justice without mercy must first tame and command them’[24].

‘A continual vexation and disquietness’

It is a mistake to see 16th century Ireland as a straightforward battle between the English and the Irish. The dispersion of Irish loyalties among hundreds of lordships, not to mention all the feuding kin-groups within them, made such an alignment impossible. The conflict was in the final analysis between rival groups of armed landowners –Gaelic, “Old English” and “New English”, for control over land, tenants and resources. Those at the bottom of the social order would remain there regardless of the outcome.

Nevertheless, the Munster plantation took root against a background of violence and mutual mistrust in Munster between the natives and the English settlers and adminstration in Dublin.

In 1588, when Phillip II of Spain launched his “Invincible Armada” against England, the English in the south of Ireland felt far from secure. The Gaelic lords of the south coast had long contacts with Spain through trade and fishing.

Florence McCarthy, for instance, was reported to be, ‘much addicted to the company of Spaniards’, had learned the Spanish language and was, ‘fervent in the Old Religion’[25]. English officials expressed grave concerns about the loyalty of the Irish and the unreadiness of the English military in Ireland. Herbert reported of ‘a continual vexation and disquietness between the undertakers and the natural inhabitants of the country’[26].

The Spanish Armada, of course, came to grief at the hands of the English navy and of bad weather in the English channel and off the west coast of Ireland. So the military readiness of the English colony in Munster was not tested. The attitude of the native lords also remained unclear. Some Irish lords helped ship-wrecked Spaniards, others attacked them and looted their ships.

The MacCarthys – Survivors

For more on the MacCarthy clans see here.

Those Irish lords who had survived the Desmond rebellion by supporting the English forces, either from the start, or when it became apparent they were going to win, did have some success in preventing the confiscation of their lands.

The MacCarthys stayed out of the Desmond rebellion and so avoided land confiscation, but they were still vulnerable to the new settler administration

The MacCarthy Mor clan, for example, lords of most of modern Cork and Kerry, declined to join the Fitzgerald rebellion and as a result they were spared the destruction that ultimately befell much of the rest of Munster, and staved off confiscation in planation[27].

Carberry of the MacCarthys Reagh was not eligible for plantation, as the MacCarthys Reagh had been loyal in the rebellion, nor was Muskerry, the other main MacCarthy line, for the same reason.

But this did not mean they were not exposed to arrest, confiscation and even death at the hands of the settlers and occupying English troops in the years that followed.

The case of Florence MacCarthy

A look at the travails of one Gaelic nobleman, Florence MacCarthy, son of the chief of the MacCarthys Reagh, shows us how the native aristocracy fared against the English regime and its colonists in Munster.

In 1581, during the Desmond Rebellion, Florence MacCarthy, at the time in his late teens or early twenties, had led around 300 men, with the assistance of an English captain named William Stanley and his lieutenant Jacques de Franceschi, against the Geraldine rebels.

Together they drove Desmond’s followers out of MacCarthy territory, ‘into his own waste country’ where his troops could find no provisions and deserted. Florence also claimed credit for the killing of Gorey MacSweeney and Morrice Roe, two of Desmond’s gallowglass captains.[28]

Despite this, some seven years later Florence MacCarthy was arrested by Warhame St Leger, President of Munster, and sent to the Tower of London – not because of anything he had done, but on account of what he might do.

His arrest was a result of his marriage to Ellen, daughter of Donal, the MacCarthy Mor, on the grounds that, as possible inheritor of the position of MacCarthy Mor, would simply make him too powerful and too dangerous to the plantation.

St Leger warned; “How perilous that may be to make him so great…he is like to have by this marriage by which all the Clan Carthys are to be at his devotion. ‘If he should become undutiful…of which, although there be good hope to the contrary, yet what ill council he may do, he being greatly addicted to the brute sort of those remote parts’.

Preventing Florence MacCarthy from inheriting Desmond was, ‘of great consequence to our inhabitation there’, the Earl’s patent to his estate should be taken over by the Queen on his death so that, ‘English gentlemen may be there planted[29].

In order to prevent the formation of a large, armed Irish lordship, which could only undermine the plantation and English government in Munster, it was better to use pre-emptive force rather than to be caught unawares in the event of rebellion or Spanish invasion.

MacCarthy Mór and the Brownes

Donal MacCarthy Mór – Earl Clancarthy – managed to prevent the loss of lands in the Planation by citing his patent as Earl Clancarthy, granted by Henry VIII in the 1540s, but had to tolerate an undertaker named Alexander Clarke on the Clandonnell Roe lands, of which he was traditional overlord[30].

However MacCarthy Mór lost part of his lordship, not to confiscation, but through bad debts. He ended up mortgaging some of his lands, perhaps as a result of losses incurred during the war, or perhaps, as some English officials claimed, to finance his indolent lifestyle.

The end result was that he lost some land at Mollahiffe to Valentine Browne of Lancashire and his family, who had been denied a grant of land in Desmond in the plantation. Florence MacCarthy, his son in law, also took the opportunity to buy Castle Lough, a strong and well located fortification near Kinsale[31].

MacCarthy Mór’s lordship was not considered very attractive for settlement, being covered in mountains and bogs. Despite this, for more than a decade after the plantation, control over this land was the cause of constant low-level violence between rival factions of native and settler landowners.

‘Playing Robin Hood’

In 1589, Donal MacCarthy, illegitimate son of the MacCarthy Mor, launched his own private war against the Browne family, who were occupying part of his sept’s patrimony. Valentine Browne reported that Donal had, ‘gone to the woods and lyeth as an outlaw’[32].

In 1589, Donal MacCarthy, illegitimate son of the MacCarthy Mor, launched his own private war against the Browne family, who were occupying part of his sept’s patrimony. Valentine Browne reported that Donal had, ‘gone to the woods and lyeth as an outlaw’[32].

William Herbert, the Welsh undertaker with a genuine passion for reform, called for the disbandment of the undertakers bands of soldiers, ‘a superfluos charge unto her Majesty’[33], to ease tensions in the area. But Browne and other successfully argued that the situation on the ground was not stable enough for the release of their soldiers.

“He hath cruelly murdered my men, spitefully killed my horses and cattle, took prey of my town and laid diverse plots against my own life”. Nicholas Browne on Donal MacCarthy

Donal MacCarthy’s local guerrilla campaign may well have had the secret support of his father, Donal MacCarthy Mor, whose interests he enforced.

St Leger reported in June 1589 that MacCarthy Mór himself had come with 100 men into Alexander Clarke’s lands at Clandonnell Roe and expelled him, Clarke barely escaping with his life. St Leger further added that “Donal the bastard” had murdered an ‘honest subject’ for, ‘reproving him in using Irish exactions’ and was ‘out’ with 15-20 swordsmen, ‘playing Robin Hood’[34].

Valentine Browne died of natural causes in 1593 but there was no let up in Donal MacCarthy’s war on the Browne family. In that year Donal was reported to have hanged servants of Browne, O’Sullivan Beare and Patrick Garland[35].

In 1594, Valentine’s son Nicholas Browne reported, ‘[Donal] hath cruelly murdered my men, spitefully killed my horses and cattle, took prey of my town and laid diverse plots against my own life’.

Browne, in command of a troop of English soldiers assigned to him for defence of his holdings, hunted MacCarthy; ‘through woods rocks, mountains, bogs and glens’ and claimed to have reduced his band from 60 down to 3, but was unable to bring him to bay[36].

Donal MacCarthy’s main preoccupation was removing the Brownes, but he also attacked those MacCarthys and their dependents who backed his rival, Florence MacCarthy – who through marriage was also eligible to be MacCarthy Mor after the incumbent’s death.

It is probable that Donal was bribing Thomas Norreys, the new President of Munster, who never energetically prosecuted him or his band, and who recommended giving him a pardon in 1593[37]. Norreys ultimately pardoned Donal in 1596 and supported him against rival MacCarthys in Desmond.

Norreys was known for handing out pardons to other ‘wood-kerne’ or Irish bandits. For example, three brothers named MacSheehy, who were arrested in 1598 for killing pigs to provision ‘the traitor Tyrell’ – commander of Hugh O’Neill’s mercenaries, were found to have been apprehended many times before, but pardoned by Norreys, despite having been responsible for robbing from or killing members of, over 80 English families.

Now they were not so lucky. The MacSheehys had their arms and legs broken before being hanged from the north gate of Cork city[38].

A spiral into war

In theory, between 1583 and 1598, when the Ulster revolt we know as the Nine Years War arrived in the province, Munster was at peace. But the reality was that native lords were being increasingly squeezed by the ambitions of English settlers and the English military presence –whose treatment of the natives was often brutal.

The Protestant Bishop of Ardfert wrote that the nature of the Irish was, ‘only to follow their lord: not respecting any allegiance to their prince. [For instance] A follower of O’Sullivan Mor … delivered in open sessions that ‘He knew no prince but O’Sullivan Mor’ for which he lost his ears’[39].

In December 1589, for instance, St Leger, at the same time as the imprisonment of Florence MacCarthy, recommended the execution of other ‘malcontents’, Patrick Fitzmaurice, Patrick Condon, the White Knight and Donagh MacCormac, merely on suspicion that they might be disloyal. [40]

Writing of Florence McCarthy, the Bishop of Ardfert warned that, ‘he cannot forget…the loss of so many of his near kinsmen and friends, if he would, his followers and kinsmen, who have ever been bloody and desirous of revenge, would never forget’.[41]

Donal MacCarthy’s private war against the Brownes was one manifestation of the ongoing resistance to the plantation, but was far from the only one. Attacks by natives on planters escalated from 1594 onwards, both in number and in the level of violence used.[42] The Bishop’s comment that Florence MacCarthy’s followers and kinsmen were ‘bloody and desirous of revenge for the loss of so many of his near kinsmen and friends’, tells us that by 1597, such killings were widespread in Munster and were not confined to attacks by the Irish on settlers.

By the time the Nine Years War arrived in Munster in 1598, planters were warning that the native Irish were “Bloody and desirous of revenge for the loss of so many near kinsmen and friends”

The Nine Years War in Munster can be seen as a major escalation of this low-level violence against the plantation. James Fitzthomas, leader of the rebels in Munster in 1598-1601, claimed that he was going into rebellion because of the many unjust killings by the English of Irish lords and gentlemen; ‘Englishmen were not contented to have our lands and livings, but were unmercifully to seek our lives’.[43]

Rebellion or reconciliation?

This brings us back to the story of Florence MacCarthy, imprisoned without charge in 1588 on suspicion that he might be dangerous if he inherited command of the MacCarthy Mor clan.

Florence MacCarthy was sent to the Tower of London in June 1589 and held there until December. The young nobleman, who spoke and wrote English well and who took to wearing English clothes in London, clearly made a good impression however.

In late 1589 the English Privy Council instructed the Lords Justices of Ireland not to confiscate the lands or castles of Florence’s followers, to release their hostages and return their goods[44]. The following month, MacCarthy was released to live within 3 miles of London, on a bond of £1000 paid by his ally, the Earl of Ormonde. In 1593, he was allowed to return to his estates in Ireland.

But his dilemma on his return sums up that of most men of his generation and class. Even though Florence MacCarthy would receive a reasonable land settlement, it was well below his expectations as a Gaelic chieftain and certainly below what he thought he could achieve by exploiting the outbreak of rebellion and war in Ulster.

On top of that, his rival for the position of MacCarthy Mor, Donal, the ‘Robin Hood’ of Desmond, also sought to exploit the war to his own advantage – meaning that Florence had to choose carefully between siding with the English or with Hugh O’Neill.

Similarly, Donal MacCarthy, who called his rival Florence, “a damned counterfiet Englishman who would betray all the Irishmen of Ireland”, in practice had to weigh up who was his greater enemy, the English, or Florence MacCarthy?

There were thousands of men in Munster – swordsmen, displaced aristocrats, Catholic preists – who had never reconciled themselves to the English plantation and who plotted a return of the old order.

The Nine Years War would give them all, their chance. It was not until their defeat in this conflict that the Munster Plantation was made secure.

To come, The MacCarthys and the Nine Years War.

References

[1] Colm Lennon, Sixteenth Century Ireland, The Unfinished Conquest, p228

[2] Elizabeth to Fitzwilliam, 7 August 1593. Daniel McCarthy, The Life and Letter Book of Florence McCarthy Reagh, Tanist of Carberry, (Dublin 1869) p90 (from now on referred to as MacCarthy Letter Book)

[3] Calender of State Papers 1574-1585; pp. 361-362

[4] Edward O’Mahony, Baltimore, the O’Driscolls, and the end of Gaelic civilisation, 1538-1615 the Mizen Journal, no. 8 (2000): 110-127

[5] Edmund Spencer, A View of the Present State of Ireland (1596), Located at http://celt.ucc.ie/index.html

[6] Annals of the Four Masters

[7] Wilbraham to Lords Commission for Munster Causes, September 11, 1587, CSP 1586-1588 pp. 405-406

[8] Herbert to Burghley June 1588, Ibid. p532

[9] Ibid. p33

[10] MacCarthy Letter book, p21

[11] Nicholas Canny, Making Ireland British 1580-1650, (Oxford 2001). p.130-132

[12] Rory O’Donoghue Mor, who held land around Killarney; Teig MacCarthy of Mollahiffe; the MacCarthys of Clandermot in Beare and the MacCarthys of Clandonnell Roe near Bantry, all in Desmond. Also surveyed were the O’Mahonys of Rosbrin, Dunbeacon, and Kinalmeaky; and two other MacCarthys in Carberry. The escheated land in West Cork was provisionally divided into four seignories, those of Rosbrin, Cloghan, and Dunbeacon, which were south of Bantry; Glanecrym, north of Rosscarbery; and two seignories in Kinalmeaky on the Bandon river.

[13] McCarthy letter book p 16

[14] Ibid. p 17

[15] Canny, Making Ireland British, p146

[16] CSP 1588 p532

[17] CSP 1589 p52

[18] Herbert to Walsyngham, December 27 1589 McCarthy letter book p52

[19] Herbert to Walsyngam, July 12 1588, McCarthy letter book p46

[20] Ibid.

[21] CSP 1588 p533

[22] Wilbraham to Lords Commission for Munster Causes, September 11, 1587, CSP 1586-1588 pp. 405-406

[23] CSP, July 25, 1589, p222

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid. p30

[26] Herbert to Burghley, June 1588, CSP 1588-92, p 528.

[27] Owen MacCarthy to Queen Elizabeth, July 1583, McCarthy, Letter Book p.20.

[28] Florence to Burghley, 29 November 1594, McCarthy, Letter Book p.121.

[29] Ibid. p.34 He also envisaged the abolition of private armies and of the authority of an overlord over other septs and lords.

[30] Nicholas Canny, Making Ireland British p154-155

[31] McCarthy, Letter Book p.24,According to Irish custom, mortgaged land was occupied by the lender until the debt was repaid.

[32] Valentine Browne to Walsyngham, 16 October 1589, McCarthy Letter Book p50

[33] Herbert to

[34] St Leger to Burghley, June 22 1589.

[35] Barry to Popham, 22March 1593, Mccarthy letter book p88

[36] Nicholas Browne to Burghley, December 4 1594, McCarthy letter book p 123.

[37] Geoffrey Fenton to Burghley, March 15 1593, McCarthy letter book p 87

[38] McCarthy letter book pp148-149

[39] Gray, Herbert, Spring, Nicholas and Thomas Browne, Bishop of Ardfert to Privy Council, February 12, 1597, MLB p152

[40] St Leger to Lords, December 7 1588, McCarthy, Letter Book p.55

[41] Ibid..

[42] MacCarthy Morrogh, The Munster Plantation, Oxford 1986. pp 130-135

[43] Fitzthomas to Ormonde, 12th October 1598, McCarthy, Letter Book,p.176

[44] Privy Council to Lords Justices, 15 December 1590 McCarthy, Letter Book p.77