‘Slaves or Freemen?’ Sean McDermott, the IRB and the psychology of the Easter Rising

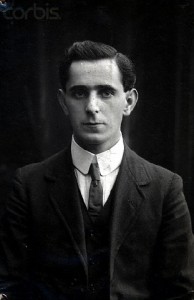

Sean McDermott has been described as, “the mind behind the Easter Rising”. He wrote that he was “never so happy” as when facing execution after it. John Dorney tries to find out why.

For an introduction to the Rising, see here.

Sean McDermott woke up on Easter Sunday, April 23rd , 1916, expecting to be launching an insurrection in Dublin city. When he found out that it was not going ahead, that it had been frustrated by Bulmer Hobson and Eoin MacNeill, respectively Secretary and Chief of Staff of the Volunteers, he was enraged and crestfallen. “It was the first and only time”, one Volunteer remembered, “that I saw Sean really upset”.[1]

Sean McDermott woke up on Easter Sunday, April 23rd , 1916, expecting to be launching an insurrection in Dublin city. When he found out that it was not going ahead, that it had been frustrated by Bulmer Hobson and Eoin MacNeill, respectively Secretary and Chief of Staff of the Volunteers, he was enraged and crestfallen. “It was the first and only time”, one Volunteer remembered, “that I saw Sean really upset”.[1]

Of Hobson, he said that he would, “damn soon deal with that fellow” and had him kidnapped and held at gun-point until the Rising could be put back on track.[2]

MacNeill was merely circumvented by getting in touch with reliable Volunteer units that the rebellion would, in spite of O’Neill’s countermanding order, go ahead.

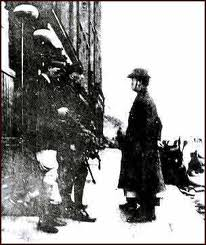

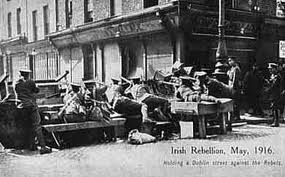

Six days later, the Rising was over. The Volunteers and Citizen Army had surrendered. Dublin city centre had been made a battlefield, some of its finest buildings destroyed by fire and shells and some 500 people were dead.

One of his comrades, Sean Murphy, a Volunteer fighter and longtime IRB member, met him as they were being marched into captivity. “Well that’s all Sean,” he recalled saying, “I wonder what’s next”. McDermott replied, “Sean, the cause is lost if some of us are not shot”. Murphy was taken aback, “Surely to God you don’t mean that Sean, aren’t things bad enough?” “They are”, he said, “so bad that if what I say does not come true they will be very much worse”.[3]

“The cause is lost if some of us are not shot”: Sean McDermott after the Volunteers’ surrender, 1916.

Thanks to the intervention of G Division detectives, who identified him to the British, days later Sean McDermott, along with the other signatories of the Proclamation of the Republic was indeed facing execution.But he was no longer depressed, far from it. In a letter written while awaiting execution he wrote, “I feel happiness the like of which I have never experienced. I die that the Irish nation might live!”[4]

There is something a little alarming to modern sensibilities about this. Unfriendly observers have called it a kind of madness and likened the rebels of 1916 to suicide bombers. Could it have been that McDermott, crippled by polio fours years previously, was expressing his rage at the world through the medium of violent revolution? Was the rebellion a “Blood Sacrifice” – an irrational act, planned and undertaken by psychologically unstable people?

An able and talented organiser

A closer look at Sean McDermott doesn’t sustain this. First of all, though only 32 years old, he had demonstrated considerable talents as a political organiser. He was well-liked and respected in the separatist movement on both sides of the Atlantic. He had run an election campaign for Sinn Fein candidates in his native Leitrim in 1908, he had operated as a nationwide organiser for the IRB since 1908 and as commercial manager for the newspaper Irish Freedom – a demanding fulltime role.

A closer look at Sean McDermott doesn’t sustain this. First of all, though only 32 years old, he had demonstrated considerable talents as a political organiser. He was well-liked and respected in the separatist movement on both sides of the Atlantic. He had run an election campaign for Sinn Fein candidates in his native Leitrim in 1908, he had operated as a nationwide organiser for the IRB since 1908 and as commercial manager for the newspaper Irish Freedom – a demanding fulltime role.

On top of that, his personal correspondence doesn’t reveal hints of any mania. He had a stable, long term relationship with Min Ryan. His bout of polio, which lost him the use of his left side, must have been a terrible blow to a previously healthy and active young man. It was also followed directly by the death of his father, which, “knocked me about a good deal”,[5] and he showed considerable psychological strength to come back from both misfortunes and resume his political work.

Nor is that all. Surely a bloodthirsty maniac would have wanted to fight to the bitter end, to die fighting and leave not a single Volunteer alive? This could have happened to McDermott’s group at the end of Easter Week. They were surrounded at Moore Street, but in strong positions and could have made a bloody last stand in the little streets and alleys there. But McDermott, far from seeking martyrdom, persuaded the younger Volunteers to surrender to save further loss of life, both rebel and civilian. Himself and the other leaders, he assured them, would be the only ones who would be shot.[6]

A highly capable, brave and psychologically strong activist organised a Rising he knew did not have mass support and which he knew could not succeed militarily. Why?

So we are left with a puzzling question. We have a highly capable, brave and psychologically strong activist, who organised and helped to lead a Rising he knew did not have mass support and which he must have known could not succeed militarily. He was thrown into the deepest depression when faced with the prospect that it would not come off and declared that he had never been happier than when facing his own execution as a consequence.

What was so important that it justified armed uprising and his own death? To answer this question, we have to look at the ideology of the organisation to which Sean McDermott devoted his life – the Irish Republican Brotherhood or IRB.

‘Slaves or Freemen’ – the IRB attitude

The IRB in 1916 was no longer a mass organisation, as it had been in the 1860s. It had about 1,300 members, organised into small ‘Centres’ throughout Ireland. But its influence was felt across a broad cross-section of nationalist organisations that it had infiltrated, from the cultural organisations, the Gaelic League and GAA to the political party Sinn Fein, to the Irish Industrial Committee and most significantly, from 1913, the nationalist militia, the Volunteers. Its influence in short was felt far beyond its own ranks.

Above all, what the IRB represented was an idea. This was the idea that Ireland was a country occupied by Britain, especially England, and historically subordinated, humiliated and oppressed.

Sean McDermott’s father had been a Fenian in Leitrim, where traditions of land agitation, resistance to landlords, police and troops, dating back to the Ribbon society of the early 19th century, merged national and agrarian issues inextricably. McDermott wrote of his father, “It was great to see how hopeful he was of the national cause up to his death, there was something wonderful in the faith of the men of that generation”.[7] He himself wrote in 1903, not very prudently, in an essay on the British Empire in an entrance exam to the British teaching system, “Colonies are of use to England but for poor Ireland nothing is of any use until the yoke of English tyranny is shaken off”[8].

“Our country is run by a set of insolent officials, to whom we are nothing but a lot of people to be exploited and kept in subjection”:Irish Freedom, 1911

Irish Freedom, the IRB newspaper argued in 1911; “Our country is run by a set of insolent officials, to whom we are nothing but a lot of people to be exploited and kept in subjection. The executive power rests on armed force that preys on the people with batons if they have the gall to say they do not like it”. [9]

This was not a fantasy. Ireland was governed by three British officials appointed in London, the Chief Secretary, the Under-Secretary and Lord Lieutenant. They and their administration controlled the armed forces and the police. Elsewhere in the United Kingdom, the police were under the control of elected local governments. In Ireland they were paid for by Irish taxpayers but answered to Dublin Castle.

There were many aspects to the separatist vision of Ireland – cultural, economic, and social and political. But the over-riding point, uniting all the others was a refusal to accept that the British state had any right to be in Ireland and that any acceptance of this made Irishmen, “slaves”, “lackies” and “toadies”. On the visit of King George V to Dublin, in 1911, for example, Irish Freedom declared, under the title, “The English King and Irish Serfs”; “we owe him or his people or Empire no gratitude or hospitality”. He was, “Guarded by spies and mercenaries and welcomed by helots [slaves]”.[10]

The Irish Parliamentary Party, who McDermott derided as, “place hunters”, “dastards, cowards and slaves”[11], were, for the separatists, engaged in their parliamentary politicking in, “slavish grovelling at the feet of England ” – whereas the republicans would, “stand out before the world like men and wring full liberty from England”.[12]

This was an attitude that was wider than just nationalism. For those committed to the separatist identity, it was personal. In an article in February 1911, Irish Freedom wrote, “we stand for self-development individually and as a nation. If we do not go forward we must collapse. It is a matter of life or death”.[13]

The IRB saw themselves as a minority who insisted on principle among a supine majority and respected people who stood up for themselves. The campaigners for women’s suffrage, were applauded as “fighters for freedom” and “political prisoners”, while strikers in 1913, were “engaged in a great spiritual revolt”. The impressionist painters were welcomed to Dublin in 1911 for thier, “determination to achieve self-expression”. [14]

At the back of this kind of adamance was a psychological rejection of British rule, with its implicit assumption that the Irish were unfit for self government – the attitude a French observer, living in Dublin, thought was, “a gentle, quiet, well meaning, established, unconscious, inborn contempt”.[15] To the separatist mind, Irishmen (always men) who accepted that Irish self government was a concession that should be asked for, rather than a right, had accepted their status as inferior and that the oppression of Irish people in the past, “The priest hunters! The Rack! The half hangings of ‘98! The Famine when one million slowly starved to death!”[16], was somehow justified.

Ideology as spur to insurrection?

Is the assertion of this attitude what caused the Easter Rising? There is no doubt that the fusing of personal identity with national self-determination had a powerful emotional charge for activists. The IRB from 1910, would insist with regularity that the only way to extract British concessions was at the point of a gun. “Freedom”, Irish Freedom declared, “requires strong methods”. The only way for Ireland to be really free was to determine her own future – by armed action if necessary. And armed revolution would also be beneficial in itself – it would teach Irishmen to take power into their own hands and by self-sacrifice, forge a new, more honourable nation.

We know that Tom Clarke, the veteran Fenian, was pushing for an insurrection since 1909 and that Sean McDermott was his closest ally in this.

But, in private, there was also a streak of pragmatism. Home Rule for Ireland, or self government within the United Kingdom, was brought before the British Parliament in 1912. While the IRB rejected Home Rule in public as, “a grotesque abortion, we stand for full independence”[17], Sean McDermott wrote to Joe McGarrity in 1913 of the Home Rule Bill, “Even in its rottenest form I hope it will get through…whatever its fate may be we are in a better position to do work than we have for many years”.[18]

So what tipped the balance in favour of armed action? Did British repression trigger a rising? Was it the growing influence of social radicalism via the new trade union movement? Or was it Catholic sectarianism in response to the Ulster Volunteers who were formed to block Home Rule?

British repression

The IRB’s position was that Ireland was under a “tyranny” and that, “Ireland is ever [always] in a state of war with the foreigner, sometimes open, sometimes smothered”.[19]

The IRB’s position was that Ireland was under a “tyranny” and that, “Ireland is ever [always] in a state of war with the foreigner, sometimes open, sometimes smothered”.[19]

As such, it highlighted every example of state repression of Irish nationalists. Under a headline of “police tyranny”, Irish Freedom reported that its copies, when transported to the provinces, were being confiscated and destroyed by the Royal Irish Constabulary.[20]

One IRB activist, Hugh Holohan, died in 1911, as a result of a battoning at the hands of the Dublin Metropolitan Police at protests during the visit of King George, “a victim of police brutality during and prior to the visit of his Britannic majesty”.[21]

Their members, Irish Freedom reported, “cannot go home without being shadowed by the Dublin Metropolitan Police’s G Division”. [22]

The IRB was subject to some repression in the pre-Rising days, but British rule in Ireland paled in comparison to for instance, Tsarist Russia in Poland.

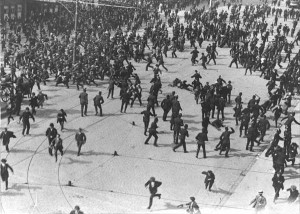

During the Dublin Lockout of 1913, the DMP were denounced as “the Dublin cossacks” – an analogy to the Tsarist troops who put down the 1905 revolution in Russia, for their attacks on striking workers. Similarly, the incident at Bachelor’s Walk, in Dublin in July 1914, in which the British Army shot dead three civlians, after the Volunteers’ importation of arms at Howth, was vilified as a massacre.

In November 1914, Irish Freedom reported that in Kerry, one Michael Murphy had been arrested and imprisoned for being in possession of a copy of the newspaper. The man who informed on him happened to be, “accidentally shot,” the day after. “It was the hand of God and no wonder”.[23]

Under the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA), introduced during the First World War, a number of IRB activists, notably Ernest Blythe, were arrested and deported for anti-recruitment agitation. Sean McDermott himself was given four months hard labour for a “seditious” speech in Tuam, county Galway in early 1915. And finally, Irish Freedom itself was closed down in December 1914 for its agitation against recruitment of Irishmen for the British forces in the First World War.[24]

But compared to a real tyranny of the day, Tsarist Russia for instance, British rule, undemocratic as it was in Ireland, was relatively mild. The IRB made much of the state’s coercive activities but much of the British administration itself thought it was far too tolerant. For instance, the Volunteers and Citizen Army staged a trial run of the Easter Rising, fully armed, just a month beforehand on St Patrick’s Day. The British, against the pleas of the Army commanders, made no arrests, no attempt to disarm them.

So if anything, it was a lack of effective repression from a British point of view that enabled the Rising to go ahead.

Social Radicalism?

If it was not a reaction agaisnt unbearable repression, was the Rising a rage against social injustice, a dream of social revolution that spurred elements of the IRB, led by Clarke and McDermott, to take up arms?

The short answer is no; but social radicalism figures increasingly prominently in the IRB’s rhetoric in the years leading up to the Easter Rising.

The IRB was interested in land agaitation and industrial conflict but principally because they brought ordinary Irish people into conflict with the state forces

In the time of Sean McDermott’s father, an IRB man at the time of the Land War in the 1880s, the position of Irish nationalists and Republicans on the social question had been fairly clear cut. They were on the side of the ordinary Irish people trying to wrest the land of Ireland from the mostly Anglo-Irish landed class, “the descendants of the robber horde sent over by Elizabeth, James, Cromwell and William of Orange”[25]. The IRB of that time had been to the forefront of the Land League.

But by the second decade of the 20th century, things were more complicated. Since the 1903 Wyndham Act, Irish tenants had bought their land with British government loans, over 70 years at 3% interest, from landlords. Whereas in 1870, 97% of land was owned by landlords and 50% by just 750 families, in 1916, 70% of Irish farmers owned their own land. The Irish export trade in cattle and dairy products was also booming and much of rural Ireland had never been better off. Incomes had increased every year since 1841 by an average of 1.6% per annum and agricultural wages had gone up 200%.[26]

The IRB was not blind to these new realities. Irish Freedom in 1911 reported that, “We cannot understand people talking about ‘poor Ireland’ in these days. Ireland is as stuffed with money as an old sock…People can eat and drink and not die”. Partly as a result, “Compromise has eaten like a cancer into our political life”.[27]

However the land question did remain important in parts of the country where farms were very small, such as Sean McDermott’s native Leitrim, where landlords still held large tracts and in the west, where tenant farmers were being displaced by cattle graziers. McDermott himself was involved in physically blocking an eviction in 1908.

Irish Freedom in April 1914 featured an article declaring, “the land question to the front”, calling for renewed agitation for, “radical reform of the land system” – essentially resistance to evictions and in favour of compulsory sale of landlords’ land to tenants. In county Galway, most of the IRB’s manpower (who brought out some 7-800 men in the Easter Rising), were also members of an agrarian secret society.

One IRB man called on McDermott to disassociate the movement from agrarian agitation, “they’ll make cattle drivers out of us”. But McDermott was hard-headed enough to see the importance of the land question for recruitment of fighters and activists. “If we curtail these men too much, we’ll have none in our ranks”.[28]

However, the most pressing social question on the pages of Irish Freedom in the years 1910-1914 was not on the land but in the cities, especially Dublin, which was rocked by strikes –notably the Lockout of 1913, in those years.

The IRB argued, “the cause of Irish liberty is more the cause of the people than the plutocrats”[29], but it was not a socialist organisation. It was committed to developing Irish industry, which they argued, would make Ireland capable of easily supporting 20 million people. They argued that class conflict in Ireland was so bitter because Britain had wrecked Irish trade. Some strikes, it argued, were the fault of employers and some of workers, “but the vast majority are the direct result of the British connection”. “Class War”, it argued, was, “incidental to commercial decadence”.“Independent Ireland would of course, have disputes between capital and labour, but they would be fights to re-adjust a balance, not a fight to the death”.[30]

But at the same time, in these labour conflicts, the IRB placed itself on the workers’ side. They defended the ideas of socialists from their enemies in the press, “vast amounts of unmitigated rubbish is written on the horrors of socialism”, And argued for a compulsory system of grievance resolution for workers and argued that the edge could only be taken off class conflict by better workers’ rights.

Sean McDermott had his fears over the effects that strikes would have on Irish industry, “socialism and the sympathetic strike are dangerous and ruinous weapons in Ireland at the present time”, and over the socialist workers’ leader Jim Larkin, “Larkin is not a nationalist”, but also noted that, “he [Larkin] did good work with a difficult crowd and against terrible opposition in getting them better conditions”.[31]

But social questions were principally important to the IRB because they brought ordinary Irish people into conflict with the state forces. Writing of violence during the lockout in Dublin in August 1913, in which the Dublin Metropolitan Police beat to death two strikers, Irish Freedom wrote that this was, “an example of the methods the English Government is prepared to use to keep Ireland in submission”.[32]

In short, while the IRB was alive to the possibilities of social conflict to mobilise people against the British state, it was really a means to an end – that of an independent Irish Republic.

Sectarianism?

The IRB insisted on the primacy of Irish nationality in all aspects of life, from the Irish language, to Gaelic games, to boycotting the police and British military. Did this amount to sectarianism? The assertion of the history and traditions of one Irish community only? Was the Easter Rising a Catholic revolt aimed against the mobilised Protestant unionists of the Ulster Volunteers?

Again, the answer must be no. For the IRB, Irish nationality had nothing to do with religion and nationality superseded all sectarian divisions. The question was Ireland against England, not Catholic against Protestant. It was defined not by blood or faith, but by commitment to this world view. In fact, several of the most prominent republicans of the early 20th century –notably Bulmer Hobson and Ernest Blythe, were Ulster Protestants.

Sectarianism was a fact in Irish society. It remained the case that, as one Catholic, nationalist complained in 1905, “It is notorious that the highest positions in the government of Ireland have been and are filled by Protestants, almost wholly to the exclusion of those who professed the religion of the nation”.[33] Todd Andrews, a youthful rebel in 1916, later recalled, “we Catholics varied socially among ourselves, but we all had a common bond, whatever our economic condition, of being second class citizens”.[34]

The IRB however had little or nothing to say about this. Unionism and constitutional nationalism were both deluded in their view – both blind to the real enemy, “English tyranny”. “Unionism in Ulster”, Irish Freedom wrote in March 1914, “depends on the maintenance of religious hatred for its life”. Equally, the Irish Parliamentary Party and their affiliates in the Ancient Order of Hibernians were simply , “job-getting and job-cornering” organisations. Sean McDermott wrote in 1913 that the major blocks in the way of Irish independence were, “The Hibernians, The IPP, the clergy and the spy system”.[35]

“Ulster must not be coerced, Ireland must not be divided”:Irish Freedom, June 1914

The exclusion of Protestants from the all-Catholic Hibernians was, for Irish Freedom, “dangerous and insidious”. “Hibernianism had postponed Irish unity for a generation”, and, “Sectarianism is the decay of the genuine nationalist ideal … All sects must stand together”.[36] Or as Sean McDermott put it, “we are not out against Carson’s Volunteers but to insist on our own right of citizenship”.[37]

There were even articles applauding the formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force as a good example of Britain’s only respecting force.

There was a logical problem with this attitude however. The Irish Parliamentary Party, the United Irish League and the Hibernians were all committed to Irish self-government. The unionists were so hostile, even to Home Rule, that they were prepared to fight to prevent it.

It wasn’t as if the IRB, and particularly people like Sean McDermott, from the borderlands of Ulster and Connacht and who had lived in Belfast, were incapable of understanding this. They were adamantly against partition, “North east Ulster is as much part of Ireland as Dublin, Kerry or Clare”.[38] But they were against sectarian conflict also, “Ulster must not be coerced, Ireland must not be divided”. That some Irishmen were fundamentally loyal to Britain and not merely cowed but hostile to Irish independence, jarred badly with their view of the world.

The IRB never really came up with a solution to Ulster unionist opposition to their project. One attitude was that Orangism was simply a manifestation of religious intolerance and supremecism and would fade away if southern nationalist sectarianism were tackled and if nationalists had practical policies – “The will and capacity for a clean government, the raw material for a decent nation, without religious bias and Ulster’s specific interests not interfered with”[39] – then the Ulster Protestants would come around. They also argued that the UVF would never really fight and that the Ulster crisis was only a “sham crisis”.

A more combative attitude to Ulster unionists also sometimes appeared, however. One article in 1912 argued that Orangism was analagous to racism or the “colour problem – the direct result of one class or race exploiting another”. While the, “negro race answer to the need of capitalists for a race with brute strength and the least intellect” the, “Orange race answer to the modern captialists or landlords in Ireland for a bloodhound race to keep its position as privileged class”.[40]

Nevertheless, it is fair to say that the Rising was not a reaction to, and did not at any stage target, either northern or southern unionists.

So why the Rising?

So if it was not provoked by British repression, or fired by social radicalism, or fuelled by sectarianism, what was the spark for the Rising? What, moreover, was the cause of the form that it took – essentially an armed demonstration to demonstrate that their people were willing to fight and die for an independent Ireland?

And why the note of desperation? Speaking in Tralee in 1914, Sean McDermott told his listeners, “Nationalism as known to Tone and Emmet is almost dead in the country and a spurious substitute as taught by the IPP exists…The Irish patriotic sprit will die forever unless a blood sacrifice is made in the next few years. It will be necessary for some of us to offer ourselves as martyrs if nothing better can be done to preserve the national Irish spirit.”[41]

The key event that provoked Irish separatists into a sacrificial Rising was the Irish participation in the First World War.

In 1914, with Home Rule (inadequate as they believed it to be) on the books and with the mobilisation of nationalists into an armed body, the Volunteers, Irish Freedom sounded an increasingly optimistic note. “The young men who stand together…for Gaelic League and Sinn Fein and Republican principles, who are crowding into the Volunteers, can save Ireland and will”.[42]

They believed that the Home Rule crisis was bringing nationalist Ireland into conflict with the state. On the shootings at Bachelors Walk in 1914, Irish Freedom exulted, “The Volunteer Movement has been formally baptised in blood. Proudly and in broad daylight the armed nation has been upheld. The young men are ready to fight for Ireland. Ultimate victory is very close now”.[43] In private correspondence, Sean McDermott wrote of the Bachelor’s Walk shootings, “It will do good and all is well. That ought to open the eyes of the fools as to what Liberal government is”.[44].

Their policy could be likened that which the Basque separatists ETA coined as, “action-repression-action” –where by escalating confrontation, the state is forced into a more repressive stance and more and more people become alienated from it. It has been argued that if the IRB militants and the other rebel leaders had waited for a national crisis like the attempt to suppress the Volunteer movement, then they could have had a rebellion with mass backing and a real chance of success.

But the big spanner in the works was the First World War. It proved that not all Irish nationalists saw the world as the IRB did. John Redmond pledged their support to the British Empire in the war and took most of the Volunteers with him. According to Thomas Kettle, one of the party’s thinkers, Home Rule and Irish participation in the War would help to forge a “union of equals, based on mutual respect”.

But to Republicans and separatists generally, what this represented was the death of Irish nationalism as they undersood it. Irishmen were rejecting, it seemed, the vision of a separate, self-defined, Ireland, engaged in a submerged war with Britain.

One of Irish Freedom’s constant themes was campaigning against recruitment into the British Army. Now, at the time of “Ireland’s Opportunity”, Irishmen were not only flooding into the British Army, but nationlist politicians were telling them to! They were, to the separatist viewpoint, prepared to be “happy slaves”.

Desmond Fitzgerald, one of McDermott’s IRB colleagues later wrote, that if things continued as they were, “it would be futile to talk of ourselves other than as inhabitants of that part of England that used to be called Ireland. In that state of mind I had decided that extreme action must be taken”.[45]

Much lower down the IRB, another Fenian, Paul Galligan, wrote to his brother after the Rising, “we were surrendering the last shred of Irish nationality and we knew that we had to fight to keep Ireland from becoming a British province”.[46]

It is testimony to the emotional force of this identity, but also its fragility, that so many separatists felt it had to be defended in this way. Looked at in this way, the Easter Rising and the rebels’ reaction to it makes a lot more sense. By fighting openly, by being prepared to die for their beliefs, the men of 1916 had made a reality of their vision of Ireland as an oppressed country, longing to be free. Engaged in fierce combat during the Rising at Mount Street, two Volunteers, Patrick Doyle and Tom Walsh, shouted over the noise of battle, “Isn’t this a great day for Ireland?” “Isn’t it that?”, “Did I ever think I’d see a fight like this? Shouldn’t we all be grateful to the good God that he has allowed us to take part in a fight like this?”. [47]

Moreover, the British reaction; execution of the leaders and wholesale arrest of nationalist activists played into their hands. There could be no better demonstration to the public that the way the IRB viewed the national situation was indeed the correct way. As a result, Sean McDermott and the others could feel that they had fulfilled thier life’s work, “I know now what I have always felt, that the Irish nation can never die. Let our present day place hunters condemn our action as they will, posterity will judge us aright from the effects of our actions”.[48]

Conclusion

The separatists launched the Easter Rising in order to save a vision of Ireland and Irish identity in which they had invested so much of their own personal identity. By fighting against “the enemy”, they had rejected dishonourable compromise and asserted Ireland’s right to decide its own future.

The separatists launched the Easter Rising in order to save a vision of Ireland and Irish identity in which they had invested so much of their own personal identity. By fighting against “the enemy”, they had rejected dishonourable compromise and asserted Ireland’s right to decide its own future.

By forcing the British into coercion of Irish nationalists after the Rising, they had, in their eyes, revealed the “real” nature of British rule, which they had always argued was “a tyranny”. This is why Sean McDermott could write of his own execution, “I look on it as part of the day’s work”.[49]

Sean McDermott was happy to sacrifice his life to save his vision of Irish identity from extinction.

There are serious moral questions about this. Is it legitimate to expose other people to injury and death to preserve one’s own political identity? Is it manipulation to provoke the state into repression in order to move the people onto your side? Should they, as Bulmer Hobson and Eoin MacNeil argued, have got the people onto their side first?

Did the introduction of revolutionary violence in 1916 haunt the rest of the Irish 20th century? These are difficult and relevant questions and too broad to be tackled here.

But they are also, in a sense, irrelevant. Because such was the power of the symbols that Sean McDermott and his comrades of 1916 created – the brave fighters taking on the British Empire, the leaders going to their deaths without fear, the British cruelty, the redemption of the idea of a free Irish nation – that they continue to form the basis of modern Republican identity and to inspire people today.

References

[1] Fearghal McGarry, The Rising, Ireland, Easter 1916, Oxford University Press, 2010, p117, He was born John McDermott, but generally went by Sean McDermott or MacDermott. He signed his name on the Proclamation of the Republic, Seán Mac Diarmada.

[2]. Ibid. p117.

[3] Sean Murphy Witness Statement, Bureau of Military History, no 204

[4] Gerard MacAtsaney, Sean MacDiarmiada, The Mind of A Revolution, Drumlin, 2004, p137

[5] Sean McDermott to Joe McGarrity, 12 Dec. 1913. (Ms. 17,618, McGarrity Papers).

[6] Charles Townshend, Easter 1916, The Irish Rebllion, Penguin 2006, p246

[7] McDermott, to McGarrity, 12 December 1913.

[8] MacAtsaney, p9

[9] Irish Freedom, October 1911

[10] Irish Freedom, January 1911

[11] MacAtsany, pp. 137, 146

[12] Irish Freedom, March 1911

[13] Irish Freedom, February 1911.

[14] Irish Freedom, August 1912, October 1913

[15] Townshend, Easter 1916 p26

[16] Irish Freedom, September 1914

[17] Irish Freedom, April 1912

[18] McDermott to McGarrity, 20 December 1913

[19] Irish Freedom, September 1912

[20] Irish Freedom, February 1913

[21] Irish Freedom, August 1911

[22] Irish Freedom, July 1913

[23] Irish Freedom, November 1914

[24] Leon O Broin, The Chief Secretary, Augustine Birrell and Ireland, p160-168

[25] Irish Freedom, April 1914

[26] Jonathon Haughton, ‘The Historical Background’, in, JW O’Hagan (ed), The Economy of Ireland, MacMillan 1995, pp19 – 25

[27] Irish Freedom, January 1913

[28] MacAtsaney, Sean MacDiarmada, p164

[29] Irish Freedom, October 1913

[30] Irish Freedom, October 1911

[31] McDermott to MacGarritty, 12 December 1913

[32] Irish Freedom, October 1913

[33] Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence, p5

[34] Richard English, Ernie O’Malley, IRA Intellectual, p107

[35] MacAtsaney, Sean MadDiarmaida p 51

[36] Irish Freedom, March 1914

[37] MacAtsaney, Sean MacDiarmada, p69

[38] Irish Freedom, July 1914

[39] Irish Freedom, March 1914

[40] Irish Freedom, October 1912

[41] MacAtsaney, Sean MacDiarmada, p146

[42] Irish Freedom, March 1914

[43] Irish Freedom, August 1914

[44] MacAtsaney, Sean MacDiarmada, p72

[45] Desmond Fitzgerald, The Memoirs of Desmond Fitzgerald, p80

[46] Paul Galligan to Monsignor Eugene Galligan, November 29, 1917.

[47] Paul O’Brien, Blood on the Streets, the Battle for Mount Street, p69

[48] MacAtsaney, Sean MacDiarmada, p137

[49] Ibid.