Today in Irish History, April 24, 1916, The First Day of the Easter Rising

John Dorney tells the story of one of the most celebrated days in Irish history.

John Dorney tells the story of one of the most celebrated days in Irish history.

An introduction to the Rising is here.

On Easter Monday, James Stephens a writer, nationalist and registrar of the National Gallery in Dublin, started hearing strange rumours. There had been rifle firing in the city all day. Returning from lunch to his office, he encountered a crowd of onlookers at Stephen’s Green.

“Has there been an accident?” said I, “What’s all this for”. A ‘sleepy rough looking man’ answered, “don’t you know? The Sinn Feiners have seized the city this morning”. “Oh”, said I … “They seized the city at eleven o’clock this morning. The Green there is full of them. They have captured the Castle, they have taken the Post Office”. “My God”, said I staring at him, and turned and went running towards the Green… I saw the gates were closed and men were standing inside with guns on their shoulders.[1]

Ernie O’Malley, then a medical student, was strolling through Dublin, it was a bank holiday and he had the day off. On O’Connell Street (or Sackville Street as it then was) he saw, ‘large groups of people gathered together. From the flagstaff on top of the General Post Office, the GPO, floated a new flag, a tricoloured one of green, white and orange.

“What’s it all about? I asked a man who stood near me, a scowl on his face. “Those boyhoes, the Volunteers have seized the Post Office, they want nothing less than a Republic”, he laughed scornfully… On the base of [Nelson’s] Pillar there was a white poster. Gathered around it were groups of men and women. Some looked at it with serious faces, some laughed and sniggered. I began to read it with a smile but my smile ceased as I read, POBLACHT NA H EIREANN, THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT OF THE IRISH REPUBLIC’[2]

There were some dead horses lying on the street, testament to a skirmish between the Volunteers and a troop of British cavalry, “Those fellows” O’Malley was told, “are not going to be frightened by a troop of lancers. They mean business”.[3]

The city centre occupied

Dubliners woke up on Monday morning and suddenly found the city centre occupied by armed men (and some women) in a mixture of dark green uniforms and civilian clothes. James Connolly had mobilized the main body at Liberty Hall, the Transport Union’s headquarters. He was in command of the men O’Malley saw who took over the GPO and most of Sackville Street.

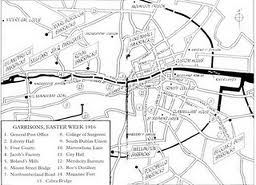

Also north of the Liffey, Volunteers under Ned Daly took over the Four Courts, the centre of the Irish legal system and the clump of little streets behind it. The men Stephens encountered on Stephen’s Green were mostly Citizen Army men, commanded by Michael Mallin. Most unwisely, they dug in on the Green, which was overlooked by high buildings on every side.

Several hundred metres away, another body of Volunteers under Thomas MacDonagh had occupied Jacob’s Biscuit Factory on Aungier Street. Further to the west, there were two main Volunteer strongpoints, one in the South Dublin Union, a vast complex of workhouses and hospitals on the site of present day James’ Hospital, under the command of Eamon Ceant, the other in Jameson’s Distillery at Marrowbone lane, overlooking the Grand Canal. Finally, at the other end of the canal to the south east was a garrison led by Eamon de Valera, ensconced in Boland’s Mill. A detachment of this force guarded the canal crossing at Mount Street Bridge and another covered the military barracks at Beggar’s Bush.

The rebels’ positions were designed to hold off a counter attack from the city’s five military barracks, but they failed to take or destroy the train stations or the ports.

Dublin’s old centre can be imagined as an elongated oval, like a misshapen rugby ball, bisected by the river Liffey, which runs from one end of the oval to the other. Its perimeters are bounded by two canals, the Royal on the north side and the Grand to the south. Running roughly parallel to the canals are two Circular roads, again North and South. This was the area the insurgents wanted to hold.

However, in 1916, this district was abutted by no less than five British Army barracks, three around the southern rim of the oval along the Grand Canal, another at Kilmainham, at the oval’s western point and one more, just beyond the Four Courts on the river Liffey. Broadly speaking, with the exception of the headquarters at the GPO, the Volunteer’s positions had been chosen as defensive sites against a counter attack from these barracks.

However, strategically speaking, there were some major flaws. The rebels had left two imposing and highly symbolic buildings in British hands, right in the centre both of the city and of their positions. Dublin Castle, the centre of British rule and Trinity College. The Castle had been attacked by a small party of Citizen Army fighters, but, after shooting a policeman, they had found the gates locked and retired to the rooftop of the adjacent City Hall, from where they exchanged shots with rapidly arriving British reinforcements.

No attempt was made to take Trinity College, the Protestant and largely Unionist University, which stood right in the path between the rebel garrisons north and south of the Liffey. A scratch force or armed students was put together to defend it and as the week went on, further British forces were funneled in.

Just as seriously, the Volunteers failed to take or put out of action either of Dublin’s two train stations – at Amiens Street (now Connolly) and Kingsbridge (now Heuston) which the British would use to bring in reinforcements from their garrisons in The Curragh and Belfast. Finally, while some of the bridges over the canal, at Marrowbone lane and Mount Street particularly, were strongly held, others were not manned at all.

The result was that instead of a compact city centre stronghold, the insurgents ultimately found themselves in isolated positions which had to withstand British counter attacks more or less alone. By the end of the week, communications between the rebel posts were only kept open by the odd Cumman na mBan (female) messenger who braved the hostile areas in between.

Dubliners’ reactions

For most of Dublin’s citizens, the rising was a bolt out of the blue and from the civilians the Volunteers at first experienced utter incomprehension and not a little hostility. Ernie O’Malley recalled the reaction of people in his middle class neighbourhood, “The loyalists spoke with an air of contempt, ‘the troops will settle the matter in an hour or two, these pro-Germans will run away’…The Redmondites were more bitter, ‘I hope they’ll all be hanged’, … ‘Shooting’s too good for them. Trying to stir up trouble for us all’.”[4]

Most Dubliners were bewildered by the Rising at first. Some were downright hostile to the rebels.

In the working class areas off Sackville street, Jacobs factory and the South Dublin Union, many people had dependents serving in the British Army in the Great War. Wives of soldiers were paid ‘separation money’, and these women were bitterly hostile to the insurrection. O’Malley heard women abusing the Volunteers outside the GPO, “you dirty bowsies, wait till the Tommies bate yer bloody heads off”, “If only my Johnny was back from the front you’d be running with your bloody well tail between your legs”[5]

Elsewhere the Volunteers had occupied places of work and welfare (such as there were) of poor working class people.In several cases the rebels had to use force against the locals to occupy their positions. At Jacob’s factory, a Volunteer named Sean Murphy recalled, “some civilians had … attacked one of the Volunteers and in order to save his life they had to shoot one of the civilians”.[6]

At South Dublin Union, the Volunteers found themselves involved in a riot with locals and had to “lay out” two with rifle butts before they got into the complex.[7] At Stephen’s Green, the Citizen Army had seized passing cars and carts at gunpoint to serve as barricades, James Stephens saw a carter try to remove his livelihood from the barricades, only to be shot dead by the insurgents. “At that moment the Volunteers were hated.”[8]

The British reaction

If the initial civilian reaction was one of bewilderment, the British were almost equally astonished. Many of their officers had been at the Races in Fairyhouse and there were only around 400 troops left in the city[9].

Lord Wimborne, the Lord Lieutenant, who had urged the suppression of the Volunteers, his worst fears having come to pass, declared martial law and handed over power to General Lowe[10]. If nothing else, the rebellion had at least freed him to clamp down on “sedition” as he had been recommending for months.

On the first day of the Rising, there were, by and large, only brushes between the Volunteers and the British military. Two troops of British cavalry, sent out to investigate the strange happenings were badly shot up on O’Connell Street and on the quays in front of the Four Courts. A bomb was detonated at the Army’s arms dump in Phoenix Park, failing to destroy the arsenal but killing an unfortunate bystander.[11]

On Mount Street, a group of reserve volunteer soldiers, nicknamed in Dublin, the “Gorgeous Wrecks” (because of their advanced age and their tunics’ inscriptions ‘Georgius Rex’), unwittingly stumbled upon the rebel position and four were killed before they scrambled into safety at Beggars Bush barracks.[12]

In fact, had the rebels known of the weakness of the British garrison, they could have taken such important points as Dublin Castle (garrisoned by only seven soldiers)[13], Trinity College (no garrison) and Beggars Bush (held initially by the army catering staff and 17 rifles)[14] with relative ease. Only at South Dublin Union, which was attacked by troops from the adjacent Kilmainham barracks, was there serious fighting on the first day, and there the British command ordered a halt until they had come to terms with what they were dealing with.

‘A horrible procession’ – the breakdown of law and order

So, sitting in disconnected positions, with a civilian population at best ambivalent, the Volunteers awaited the British counterattack.

Three of the unarmed Dublin Metropolitan Police were shot on the first day of the Rising and their Commissioner pulled them off the streets. The decision, though understandable, unleashed an orgy of looting, especially around Sackville Street, as slum dwellers from the surrounding area took the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to ransack the city’s shops and boutiques[15].

Ernie O’Malley recorded that for the slum dwellers, “this was a holiday. Some of the women…walked around in evening dress. Young girls wore long silk dresses. A saucy girl flipped a fan with a hand wristletted by a thick gold chain… She strutted in larkish delight, calling to others less splendid, “How do yez like me now?”.[16]

According to another onlooker, “a horrible procession poured into the streets, mainly women and girls…they started with sticks and stones, a breach would be made [in a shop], the door would be forced in”, if the shopkeeper resisted, “they would beat him and down him without mercy”. A total of 425 people were arrested after the Rising for looting[17] The Volunteers tried but largely failed to keep order and were reduced to shooting over the heads of looters to try and disperse them.

So, sitting in mostly disconnected positions, with a civilian population at best ambivalent, at worst downright hostile, the Volunteers awaited the British counterattack.

For the following day, see here.

References

[1] James Stephens, The Insurrection in Dublin, pp3-7

[2] O’Malley, On Another Man’s Wound, p 34-35

[3] Ibid.

[4] O’Malley On Another Man’s Wound p37-38

[5] O’Malley, p39

[6] Annie Ryan, Witnesses, p121

[7] Charles Townshend, Easter 1916, The Irish rebellion, p174

[8] Stephens p18

[9] Townsend p183

[10] Tim Pat Coogan, The Easter Rising p107

[11] Ibid.

[12] Paul O’Brien, Blood on the Streets, the Battle for Mount Street, p22-23

[13] Townshend p163,

[14] Ibid. p177

[15] Coogan p103-104

[16] O’Malley p40-41

[17] Townshend p263-264