Today in Irish History, April 30, 1916, The Surrender in the Easter Rising

Over April 29th to May 1, 1916 the rebels of the Easter Rising surrendered. This is an adapted extract from John Dorney’s The Story of the Easter Rising.

Over April 29th to May 1, 1916 the rebels of the Easter Rising surrendered. This is an adapted extract from John Dorney’s The Story of the Easter Rising.

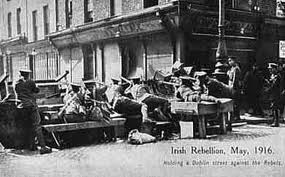

The Easter Rising in Dublin had broken out on Easter Monday, April 24th with the Volunteers and Citizen Army occupying much of the city centre. Their headquarters at the GPO on O’Connell Street was bombarded by British artillery and by Friday, the grand buildings of Dublin, having burned fiercely for two days, were crashing down around them.

Ernie O’Malley, a medical student watched from the northside, “The fire had spread, it seems as if the whole centre of the city was in flames. Sparks shot up and the fire jumped high as the wind increased”.[1]

The Post Office itself had caught fire and was becoming untenable, forcing an evacuation to nearby Moore Street. A sortie led by Michael O’Rahily led the way but was badly shot up – 21 out of 30 men were hit by fire from the ever closer British barricades. O’Rahily himself was killed and lay sprawled, face up, on Henry Street in full view of his comrades. The survivors, led by Pearse and Plunkett, escaped the blazing Post Office into the little streets around Moore Street where they tunneled through the walls, to make the terrace one long bastion.

The Surrender at Moore Street

On Saturday the 29th of April, Pearse issued orders to surrender. The remnants of his command from the GPO were cornered in and around Moore Street. O’Rahily was dead, Connolly was badly wounded – he had a bullet wound to the ankle which had turned gangrenous.

There was talk of trying to break through to Daly’s men around the Four Courts but it proved to be no more than that. In reality the Volunteers and Citizen Army men were tightly ringed by British rifles, machine guns and artillery on all sides.

Three elderly civilians who tried to escape from Moore street towards the British barricades was swept away by a storm of bullets from the barricade in front of Pearse’s eyes. It was this, apparently that moved him to surrender. According to Sean McDermott, “when Pearse saw that, we decided we must surrender to save the lives of the citizens”. Also that day, British troops had broken into houses on North King Street and killed 15 civilians whom they accused of being rebels, but Pearse had not seen and probably did not know about this.[2]

Sean McDermott had to persuade the younger Volunteers at Moore Street to obey the surrender order.

Pearse sent a tersely written note, via a Cumman na mBan nurse named Elizabeth O’Farrell, to General Lowe, stating he wished to surrender to, “prevent the further slaughter of the civilian population and in the hope of saving our followers, now hopelessly surrounded and outnumbered”.[3]

Some of the younger Volunteers wanted to make a last stand in Moore Street. Had they done so, they would no doubt have crowned off the “blood sacrifice” with their own deaths and many of the assaulting British troops, but they were talked out of it by some of the older heads. Sean McDermott in particular argued that they had done all that could be expected and that only the leaders (such as himself) would be executed. Pearse was taken to see General John Maxwell, the newly arrived British commander, to confirm the unconditional surrender in person.

Pearse’s surrender came late on Friday afternoon. The survivors of the GPO garrison emerged blinking from their Moore Street enclave and assembled at Nelson’s Pillar, where they piled their arms and were marched to captivity in Richmond Barracks.

‘A greater calamity than death itself’

Word still had to be got to the other rebel strongholds, however, none of which had yet been taken by the British. Elizabeth O’Farrell, accompanied by a priest, volunteered to bring the news to the Volunteers around the city.

Word still had to be got to the other rebel strongholds, however, none of which had yet been taken by the British. Elizabeth O’Farrell, accompanied by a priest, volunteered to bring the news to the Volunteers around the city.

It is often assumed that all of the rebel garrisons shared the experience of the GPO –bombarded into surrender. In fact, apart from the rebel headquarters, only Boland’s Mill had been the target of a (rather inaccurate) artillery barrage.

Elsewhere, some garrisons, at Jacobs Factory, The Four Courts and The College of Surgeons, had seen little action. Others, especially South Dublin Union and the adjoining Marrowbone lane Distillery and North King Street, were still resisting tenaciously.

So when Elizabeth O’Farrell arrived with the Pearse’s order to surrender, at first, many of the rebel commandants didn’t believe her. Eamon de Valera at Boland’s Mill sent her away and had to be persuaded by officers who knew her that she was genuine. Thomas MacDonagh in Jacobs factory thought the British had forged the note or forced Pearse to sign. In Marrowbone lane, full with over 100 Volunteers and Cumman na mBan women, the rebels were convinced they were winning and had organized a victory ceilidhe for that night.[4]

Many rebels did not see why they should surrender and for those who had not seen fighting, the shame was almost unbearable

James Stephens was clear that despite the surrender at Moore Street, the insurrection was still not over on Saturday, “there is much rifle fire, but no sound from the machine guns, 18 pounders or trench mortars.”[5] It was Sunday the 30th before the last rebel garrisons, at South Dublin Union and Marrowbone lane reluctantly surrendered.[6]

For many Volunteers, especially those who had seen very little fighting during the week, the shame of surrender was almost too much to bear. Frank Robbins, a Citizen Army man, left an evocative account of the surrender in the College of Surgeons, “the act of surrender was a greater calamity than death itself. Men and women were crying openly with arms around each other’s shoulders”. It was only when British troops arrived that they recovered their composure, “we had nothing to be ashamed of”, they might have failed but, “others had failed before and they had not been ashamed or afraid of the consequences, why should we be?”.[7]

Some rebel commanders like Joe McGrath at Marrowbone lane told his men to escape and did so himself with a, “Toor a loo boys, I’m off”.[8] Michael Mallin, the Citizen Army commander also told anyone who thought they could escape to do so, as did John McBride in Jacobs factory, adding, if they ever got the chance to fight again, “don’t get inside four walls”.[9]

De Valera on the other hand, insisted his men had to follow the surrender order to the letter and they marched in formation into captivity.

Enniscorthy and Ferns in County Wexford had been occupied by the local Volunteers on Thursday, who hoisted the republican flag over the town hall and set about fortifying their positions against a counter attack.

By Sunday morning, there had still not been any sighting in Enniscorthy or Ferns of the British forces whom they knew were assembled at Arklow and Wexford town. Later that afternoon, an RIC District Inspector and Sergeant had arrived at Ferns under a flag of truce with a copy of Pearse’s surrender order.

At first, Seamus Doyle and his officers in Enniscorthy refused to believe the surrender order. He and Sean Etchingham of Gorey applied to the British commander French for permission to travel to Dublin and see Pearse in person. French put them in a military car and had them driven them to Arbour Hill prison in Dublin where Pearse was being kept.

Doyle recalled, Pearse looked, “physically exhausted but spiritually exulted. He told us that the Dublin Brigade had done splendidly – five days and nights of continuous fighting…Etchingham said to him, ‘Why did you surrender?’, Pearse answered, ‘because they were shooting women and children in the streets. I saw them myself’.”[10]

Pearse had not been aware of the Rising in Enniscorthy but agreed to sign a written order to the Wexford Volunteers confirming the surrender, that Doyle and Etchingham brought back to Enniscorthy.[11]

At Ashbourne in county Meath, the North County Dublin Volunteer contingent had won a skirmish with the local RIC and were camped a Kilsalaghan when they received the surrender order. Like many of the city contingents they surrendered most reluctantly.

In county Galway, 350 Volunteers under Liam Mellows were ensconced at Myode Castle and Lime Park. But even had they wanted to make an Alamo of their positions, they were not equipped to do so, with only 50 rifles between them. When they heard the news of the arrival of British warship in Galway bay, which landed 200 Royal Marines and which began shelling the area, they dispersed. A sympathetic priest, Father Fahy told them they had, “made their gesture and must preserve their lives for the next fight”.[12]

Aftermath

Ernie O’Malley wandered into O’Connell Street – a scene of devastation – after the fighting had ended. “The GPO was a shell from which the tricolour still floated. The stout walls were blackened, but they still held…

Ernie O’Malley wandered into O’Connell Street – a scene of devastation – after the fighting had ended. “The GPO was a shell from which the tricolour still floated. The stout walls were blackened, but they still held…

The lower portion of O’Connell Street was in ruins. What houses still stood were being hauled down by wire ropes attached to traction engines. Houses were smouldering on Moore Street, Earl Street, Abbey Street and the Quays…Everywhere glass had been shattered or neatly drilled by bullets”.[13]

Part of the popular memory of the Rising is that the Volunteers were pelted with abuse and missiles by hostile Dubliners as they marched under escort to prison. And there is no doubt that this did happen to some rebels. Sean Murphy, taken prisoner with the Jacobs garrison, remembered that, “We were marched via Christchurch Place, High Street, to Richmond Barracks, Inchicore, all places through which we passed we were met with a very hostile reception from a section of the citizens”.[14]

According to Max Caulfield’s powerful description of 1963, “As the prisoners marched to Richmond Barracks, crowds stood at the kerbsides to hoot and jeer them, ‘Shoot the traitors!’, they cried. ‘Bayonet the bastards!’ In one of the poorer quarters the shawlies pelted them with rotten vegetables and the more enthusiastic disgorging the contents of their chamber pots over the beaten, yet somehow undefeated men”.[15]

The popular memory of the surrender is that the Volunteers were pelted with abuse and missiles by angry Dubliners. This did happen, but it may not be the whole story.

Robert Holland, a Volunteer taken prisoner after the surrender of the Marrowbone lane position, remembered that as he was being marched to Richmond Barracks, “men, women and children used filthy expressions at us”. Worst of all for Holland, a member of the Volunteer Company from the working class Inchicore area, was that he knew many of his assailants.

The prisoners, “heard all of their names being called out at intervals by the bystanders. My name was called out by some boys and girls I had gone to school with…This was the first time I ever appreciated British troops, as they undoubtedly saved us from being manhandled that evening”.[16]

This may not be the full story however. James Stephens thought that the mood in the city, though, “definitely Anti-Volunteer”, was more ambivalent. First of all, the people he talked to respected that the Volunteers, “are putting up a decent fight”. “For being beaten does not greatly matter in Ireland, but not fighting does matter”. “Had they been beaten on the first or second day, the city would have been humiliated to its soul”.[17]

Stephens thought that people had not yet taken sides; “None of these people were prepared for Insurrection. The thing had been sprung on them so suddenly they were unable to take sides”.[18] A Dublin unionist, A.M. Bonaparte-Wyse, thought, “the sympathies of the ordinary Irish are with Sinn Fein”.[19] Likewise, a Canadian journalist, F.A. McKenzie, found that, “in the poorer districts … there was a vast amount of sympathy with the rebels, particularly after the rebels were defeated.”[20]

The experience of Ernie O’Malley, the medical student who came upon the GPO takeover on Easter Monday was extreme. He actually joined in the fighting on the rebel side, sniping at British troops with a borrowed rifle and then helping fugitive Volunteers to get away after the surrender[21].

By May 1st, with much of central Dublin in smouldering ruins, corpses littering the streets and thousands of wounded cramming the hospitals, the Rising was over.

References

[1] Ernie O’Malley, On Another Man’s Wound, (Anvil 2002) p46

[2] Charles Townsend, Easter 1916 (Penguin 2006) p246

[3] Townshend p246

[4] Townsend p250

[5] James Stephens, The Insurrection in Dublin, (Colin Smythe, 1992) p 67

[6] Townshend p 246-250

[7] Ibid. p252

[8] Annie Ryan, Witnesses, Inside the Easter Rising, (Liberty 2005) p135

[9] Townshend, p250-251

[10] Seamus Doyle, Witness Statement BMH

[11] Seamus Doyle, Witness Statement BMH

[12] Fergus Campbell, Land and Revolution, (Oxford 2008) p217, See also Fearghal McGarry, The Rising, p243

[13] O’Malley, p40-47

[14] Sean Murphy Witness Statement BMH no 204

[15] Max Caulfield, The Easter Rebellion, Four Square Books, London 1963, p355

[16] Ryan, Witnesses p135

[17] Stephens p39

[18] Ibid. p57

[19] Townsend p267

[20] Ruán O’Donnell ed., The Impact of the 1916 Rising: Among the Nations, Irish Academic Press Dublin 2008, pg. 196-97

[21] O’Malley p43-47