The 1926 IRA campaign against Moneylenders.

Rhona McCord remembers the summer when the IRA in Dublin went to war against money-lenders – a campaign tainted with allegations of anti-semitism.

Rhona McCord remembers the summer when the IRA in Dublin went to war against money-lenders – a campaign tainted with allegations of anti-semitism.

‘If at the moment, squads of men, acting on my orders, are “cleaning up” the smaller fry of money lenders in Dublin’s back streets, such small activities must be considered as merely a prelude to the bigger attack on the more extensive system,’ B.H. Brig General.[1]

In the summer of 1926 the IRA launched a campaign to rid Dublin of the scourge of moneylenders. The IRA was forced to defend these activities against accusations of sectarianism, they insisted that it was in the interests of the poor of the city and was in no way anti-Semitic. The operation involved armed raids on the homes of known moneylenders and the confiscation of their ledgers, record books and documentation. The campaign, which resulted in the arrest of several members of the IRA, reflected a change in IRA policy away from the national question towards social issues.

This short-lived crusade raised serious questions about both the poverty of Dublin and the under current of anti-Semitism in Ireland in the 1920s. These incidents must be viewed in a wider context. An examination of the small Jewish community in Dublin and the reliance of Dubliners on moneylenders as a source of credit, will reveal a less than genuine motive for the IRA’s activities. A brief examination of IRA policy in 1926 must be placed in the context of a poverty-ridden society, with growing concern in some quarters to the profiteering nature of money lending.

Little Jerusalem

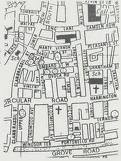

The Jewish population of Dublin settled in an area on the south side of the city centred on Clanbrassil Street and known colloquially as Little Jerusalem. The city’s Jewish population were divided into two settlement groups, the first arriving from Russia at the end of the nineteenth century and the second arriving at the beginning of the twentieth from Lithuania. The population was small and remained so as immigration became limited by the introduction of the United Kingdom Aliens Act in 1906. The 1911 census returns point to the Jewish population on Clanbrassil Street with names like Joffe, Kinigsberg and Yendole.[2]

The 1911 census recorded 3,805 Jews living in Ireland; the Aliens Act had a stagnating effect on the community, the population dropped slightly to 3,686 by 1926.[3] Outside of Dublin there were very small settlements in Limerick, Cork and Belfast. The middle class status of a large proportion of Jewish immigrants meant that they were not in direct competition with unskilled workers in the jobs market. Although the Jewish population avoided major hostility from the native population they were often the targets of an underlying prejudice from sections of the population.

Anti-Semitism in Ireland

Dermot Keogh suggested that an undercurrent of anti-Semitism can be traced back to the end of the nineteenth century and had an economic basis. Louis Hyman explained how Jewish peddling became a threat to other traders, ‘certain shopkeepers regarded all this as serious competition and in October

1886 posters were placed all over Dublin calling upon citizens to have no truck with the foreign Jews of recent arrival.’[4] Keogh gave the example of an advertisement by the Dublin Tailors Co-operative in the Leader in1904, which concluded with the line ‘Irishmen help us stamp out Sweated, Jewish Labour’.[5] The most infamous attack on the Jewish community in Ireland took place in Limerick in 1904.

An undercurrent of anti-Semitism can be traced back to the end of the nineteenth century

Sometimes referred to as a pogrom, the Limerick Boycott was an episode whipped up by one priest, Father Creagh, whose sermons were intended to inflict economic hardship on a tiny Jewish community of just 35 families. Creagh played on the ignorance of Jewish culture to whip up support for his anti-Semitic campaign. The response to Creagh’s sermons resulted in the economic devastation of the small Jewish community in Limerick. Keogh suggested this downfall was evidence of their innocence, ‘the rapidity with which the petty Jewish tradesmen became penniless scarcely corroborates the lucrative business practices- or malpractices- which were alleged.’[6]

Arthur Griffith supported Creagh’s campaign, writing in the United Irishman he stated that the campaign was ‘demanding freedom for the Irish peasantry from international moneylenders and profiteers’.[7] But another nationalist leader, Michael Davitt, disagreed entirely, he wrote to the Freemans Journal ‘I protest, as an Irishman and as a Christian, against this spirit of barbarous malignity being introduced into Ireland, under the pretended form of material regard for the welfare of our workers’.[8] The same argument regarding motives can be raised in connection with the I.R.A.’s campaign of 1926.

Attacks on the Jewish community continued in a low key way into the twentieth century. Keogh quotes a local rhyme from Little Jerusalem, which summed up an underlying mistrust,

Two shillies, two shillies’, the Jewmman did cry,

For a fine pair of blankets from me you did buy:

Do You think me von idjit or von bloomin’ fool,

If I don’t get my shillie I must have my vool.[9]

With interest rates over 100% borrowing from moneylenders no doubt caused economic hardship but for the working classes the only access to credit came via the moneylender and the pawnshop.

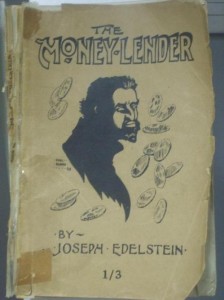

The term Jewman was common in Dublin and referred both to ethnicity and to the colloquial name for a Jewish moneylender. Cormac O’Gráda explained how the wealthier first generation Litvaks who became moneylenders or precentnik were effectively the ruling class within their community.[10] Some of the larger moneylenders operated from specific premises under official titles such as the Union Loan Bank or the Abbey Loan Bank.[11] Most operated on the basis of weekly repayments at typically high interest rates, O Gráda’s example suggested a loan of £1 could be paid back at twenty-five weekly instalments of one shilling.[12]

With interest rates over 100% borrowing from moneylenders no doubt caused economic hardship but for the working classes the only access to credit came via the moneylender and the pawnshop. It must be noted that the Jews were not the only people offering high interest loans. Many oral testimonies indicated that there were other and perhaps more precarious sources as the testimony of Mary Corbally implied, ‘In them days your first loan of a Jewman would be two or three pounds…Moneylenders, they were the worst. The money-lenders were local, they were our own neighbours. Some of them if you didn’t pay them you’d get a hammering off them’.[13]

The IRA in the wilderness

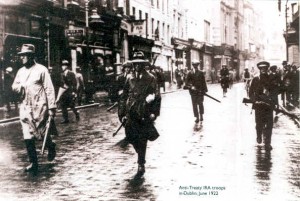

Tim Pat Coogan in his work on the I.R.A. suggested that the organisation faced a dilemma in the 1920s of violence versus politics and that this often manifested itself as ‘Force v a concentration on economic and social issues’.[14] As an army with no war to fight the I.R.A. was faced with the prospect of losing its relevance.

The nature of I.R.A. campaigns of this era reflected a need to stay active rather than a serious challenge to the state. I.R.A. activity in 1925-26 was characterised by raids on Garda stations and witness intimidation. Several attacks were carried out on cinemas in Dublin and Galway in an anti British propaganda campaign.

Activities like the anti-poppy campaign focused on soft targets and served the purpose of keeping the membership active and attracting new recruits without representing a serious threat to the Treaty. The launch of the newspaper An Phoblacht in 1925 is a good indication of an I.R.A. shift towards politics. Coogan suggested that the danger of a secret society having a public newspaper was an indication a shift in a political direction, ‘the I.R.A. found this disadvantage outweighed by the tremendous influence, not alone on Republicans, but on left-wing young people, which the paper very shortly began to enjoy’.[15] The fact that the I.R.A. did not have the military ability to carry out a full-scale uprising forced them into an alternative tactics.

The raids on the offices of moneylenders must be viewed in the context of an organisation re-organising itself and attempting to galvanise popular support. Brian Hanley suggested that this campaign was, ‘like the campaigns against ‘imperialist’ displays, the I.R.A. had chosen an unpopular target which was even more unlikely to retaliate.’[16] The fact that a large number of moneylenders were of the Jewish faith gave rise to suspicions of anti-Semitism. When Coogan described these events he stated that, ‘A touch of anti-Semitism also showed in a series of armed raids on moneylenders…at least as much motivated by a desire to stamp at the practice of money-lending as to strike at Jews.’[17]

‘I would like to express my sincere appreciation on this first move, at least to curb if not to eventually put out of business this rotten trade’: Robert Briscoe (Jewish Republican)

The Jewish Republican Robert Briscoe refuted any accusation of anti-Semitism, in a letter to An Phoblacht written one week after the first raids were carried out Briscoe stated, ‘I as a member of the Dublin Jewish community, would like…to make it quite clear that these raids were not for one moment interpreted by me as an attack on the Jewish community’.[18]

Briscoe pointed out that non-Jewish moneylenders were also visited and that the Jewish community in general was abhorred by the practice of money lending. He concluded by condoning the activity of the IRA ‘I would like to express my sincere appreciation on this first move, at least to curb if not to eventually put out of business this rotten trade’.[19] Indeed in the language of An Phoblacht this was a campaign that the I.R.A. intended to carry to a conclusion.

The Campaign

In his book on the I.R.A., Tim Pat Coogan referred to a level of seriousness within the organisation it ‘took itself with deadly seriousness… IRA policy was viewed as something sacrosanct’.[20] This is evident in the statements issues by An Phoblacht regarding the raids. With reference to the raids of the 7 July An Phoblacht described how those involved presented the lenders with notification, ‘notification presented at each office read as an instruction directing the person in charge of the party to proceed to a particular house and to make the desired seizure’.[21]

The IRA’s language is almost official as it saw itself as an alternative police force

The language is almost official as if the IRA saw itself as an alternative police force. When asked about moneylenders from across the water advertising in Irish newspapers the reply was, ‘You must wait and see’.[22] There can be no doubt that the IRA expected a successful conclusion to this campaign. The following edition of An Phoblacht reported further raids and suggested that, ‘several money-lenders have already decided to seek other occupations’.[23]

As the raids continued every feature in the pages of An Phoblacht was accompanied by a denial of any anti-Semitic intent. A letter from Eamon Martin under the heading ‘Not an attack on Jewry’, acknowledged the unconstitutional nature of the actions and contended that ‘these raids have no anti-Semitic significance.’[24] Martin’s letter identified moneylenders as a lazy minority who have damaged the Jewish community. Despite these assurances the Jewish community felt a need to defend themselves in writing at least.

Jewish community leader Wolfe Newman responded to Martin’s letter with his own letter to the Jewish Chronicle, which was re-printed in An Phoblacht with a reply from Martin.[25] This approach by AnPhoblacht, gave a sense of open debate and fairness, but revealed a genuine uneasiness about the accusation of anti-Semitism. In fact, every article about the raids published by An Phoblacht, was accompanied by a statement in some form denying that there was any sectarian motivation for these raids.

Newman gave a somewhat sanitized version of money lending in his community, he stated, ‘a habit has sprung up among the patrons of Jewish tradesman to insist upon receiving money instead of goods, and much to the regret of the tradesmen, they are compelled to retain the goodwill of their customers by advancing small loans’.[26] To Newman money lending was a position that some Jewish tradesman had been forced into by the economic hardship of their customers he went on to explain that the wider Jewish community frowned upon it and by way of further justification suggested that the profits made from usury were negligible.

Newman criticised the unconstitutional methods of the IRA against what he believed were legitimate businesses. The IRA was not concerned about unconstitutional methods and Martin’s reply to Newman did not address that issue at all. Martin concerned himself firstly with the sectarian issue, ‘it is quite obvious that these raids were in no way sectarian’[27] and then continued with a less sanitized version of usury explaining that the profits ‘while it does not awaken envy, is considerable, and furthermore they have been acquired in a very short space of years.’[28] This language does suggest a certain amount of begrudging.

Cormac O’Gráda, writing about the settlement of Dublin’s Jews, pointed out that many moved quickly up the social ladder.[29] O’Gráda noted the disproportionate number of Jewish families who employed a domestic servant. O’Gráda traced a general pattern of movement, from modest surroundings of Oakfield Place to more affluent streets like the South Circular road or Kenilworth Square.[30] It should be noted however that hierarchies exist in every section of society and there were poorer sections of the Jewish community who were not profiting from usury although very few were employed as labourers.

This apparent affluence may have been a reason for an undercurrent of ill feeling. Martin, continued in his reply to Newman with a statement about the unproductive nature of usury, it does not create employment and, ‘does not turn a single cog in the wheels of industry’.[31] It could be argued that the IRA were also non productive and in fact were putting people out of business without providing an alternative credit facility for the poor.

The suggestion that the IRA were acting on behalf imprisoned members of their own organisation whose families may have been facing debt is raised in the pages of their newspaper but is not sufficiently dealt with. This may have been the original motivation behind the raids but it gets only a brief mentioned in the discourse between Martin and Newman. Whatever the impetus was the campaign soon turned into a moral crusade by the IRA in which they placed their organisation as protectors of the poorest sections of the community and made the raids appear less cynical.

The arrests of three IRA members on July 7 involved in a raid on the home of Edward Levi of Bloomfield Avenue, gave an indication of the modus operandi of the attacks. The raid took place at ten o’clock in the morning, three IRA members forced their way into Levi’s home where they presented their victim with a letter containing instructions to hand over all of his account books. During this raid the victim managed to escape the invaders and call for assistance. The details reported in the Irish Times confirm that the raiders were acting on orders, ‘the smallest of the three handed the witness a letter’.[32]

The newspaper made no further comment about the contents of the letter but stressed that the men were armed and demanded money, which in the minds of readers may suggest that the IRA’s intentions were not entirely honourable. When charged one of the defendants was reported to have said, “The charge is false. There was no demand for money. I did not present a revolver at Mr. Levi.[33]

The charges brought against the raiders, Fiona Plunkett, Domhall O’Donohue and Mick Price revealed something of the fears of the new state. They were charged with assisting in the formation of an illegal military force and unlawful possession of arms and ammunition and treasonable documents.[34] The idea of the IRA promoting itself as an alternative police force with the support of the community was intolerable for the fledgling state. The Irish Times reporting on the court proceedings highlighted defendant Domhall O’Donohue’s address to the court in which he said ‘that the exploitation of their countrymen was contrary to Christian teaching…showed the need for a new code more suited to a Christian country’.[35]

Emphasis on the word Christian can be interpreted as anti-Semitic. The reported address concluded, ‘he would endeavour to create a public spirit hostile to the evil’.[36] This was strong language, which identified usury as a non-Christian practice and therefore could be used to create anti-Semitic sentiment. On the other hand it may have been emphasised by the media in order to discredit the IRA. An Phoblacht’s report of the court proceedings surrounding the raids suggested that the charges of theft were not true. They objected to the exclusion of their own reporters from the court and complained that the defendant and commanding officer of the Dublin Brigade, Mick Price was silenced by the judge when he attempted to address the court.[37]

The headlines in An Phoblacht continued to court popular public support. The hearings were accompanied by public demonstrations outside the courts led by high profile figures like Maud Gonne and Countess Plunkett. The latter’s daughter was one of the defendants. With this public display of support An Phoblacht could justly claim that, ‘all decent citizens are in sympathy with the campaign against money lending.’[38] A headline in October read ‘Popular Opinion Solidly Against Usury’.[39] This article hinted at an end to the campaign with talk of peace terms and the involvement of the clergy and other community groups in brokering a settlement with the moneylenders. An uncertain settlement followed and the IRA withdrew from the campaign without really ending the practice or advancing the campaign beyond the so-called ‘small fry’.

Although the pages of An Phoblacht addressed the specific dangers of money lending and its potential to cause severe hardship, the wider issues of poverty and unemployment were not dealt with in any specific detail. The fact remained that the moneylender played a key role in the daily lives of the poor who had no alternative source of credit and the raids did not tackle this issue. The practice remained unrestrained by the law until Robert Briscoe, who as a TD for Fiánna Fáil, brought in legislation in 1932 to control the interest rates on loans.

Conclusion

The summer raids of 1926 were controversial because of the suggestion of anti-Semitic intent. Tim Pat Coogan described the raids as having ‘a touch of anti-Semitism’ but did not produce any credible evidence to confirm this suspicion. Taking a later historical view from the 1940s, it would be easy to trace a line back to 1926 to imply that anti-Semitic feeling had a history in the IRA. However there is not sufficient evidence to support the accusation of anti-Semitism in 1926.

The raids may have begun as an opportunist activity to aid IRA supporters who had personal financial problems then developed into a wider campaign

If the raids began as an opportunist activity to aid IRA supporters who had personal financial problems then its development into a wider campaign must be seen as a cynical attempt to cover up their motives and at the same time inspired a recruitment campaign amongst the Dublin working classes. Individuals within the ranks of the IRA may have held anti-Semitic views but it is unlikely that those views would have translated into a public campaign against the Jewish community. Mick Price, who had a key role in the leadership of the Dublin Brigade, was to the left of the Republican movement and would have found it very difficult to justify a high profile anti-Semitic campaign. The attacks may have had a sectarian intent for some of the participants but the evidence does not support an official anti-Jewish policy within the IRA. The campaign did however smack of opportunism and a cynical attempt to gain popular support from the most desperate layers of Irish society.

Primary Sources:

National Archives 1911 Census at www.nationalarchives1911census.ie

Newspapers;

The Irish Times.

An Phoblacht.

Freeman’s Journal.

Secondary sources:

Coogan, Tim, Pat, The I.R.A. (London, 1970).

Hanley, Brian, The IRA 1926-1936 (Dublin,2002).

Harris, Nick, Dublin’s Little Jerusalem (Dublin, 2002).

Hyman, Louis, The Jews of Ireland From Earliest Times to the Year 1910 (Shannon, 1972).

Kearns, Kevin, C., Dublin Tenement Life: An Oral History (Dublin,1994).

Keogh, Dermot, Jews in Twentieth Century Ireland: Refugees, anti-semitism and the Holocaust (Cork, 1998).

Keogh, Dermot & McCarthy, Andrew, Limerick Boycott 1904: Anti-Semitism in Ireland (Cork, 2005).

O’Grada, Cormac, Jewish Ireland in the age of Joyce; a socioeconomic history (New Jersey, 2006).

O’Grada, Cormac, ‘Settling In: Dublin’s Jewish Immigrants of a Century Ago’ in Field Day Review Vol. 1. (2005) pp. 87-100.

[1] An Phoblacht, 13 August 1926.

[2] National Archives: Census of Ireland 1911, available online at www.nationalarchives.ie

[3] Dermot Keogh & Andrew McCarthy, Limerick Boycott 1904: Anti-Semitism in Ireland (Cork, 2005) p. 3.

[5] Dermot Keogh, Jews in Twentieth Century Ireland (Cork, 1998) p. 54.

[6] Ibid-p. 215.

[7] Ibid-p. 213.

[8] Freemans Journal 18 January 1904.

[9] Keogh, Jews in Twentieth Century Ireland p. 63.

[10] Cormac O’Gráda, Jewish Ireland in the Age of Joyce: a Socioeconomic History (New Jersey, 2006) pp. 61-62.

[11] Ibid-p. 62.

[12] Ibid-p. 63.

[13] Kevin C. Kearns, Dublin Tenement Life: An Oral History (Dublin, 1994) p. 205.

[14] Tim Pat Coogan, The I.R.A. (London, 1970) p. 38.

[15] Ibid-p.47.

[16] Brian Hanley, The I.R.A., 1926-1936 (Dublin, 2002) p. 76.

[17] Coogan, p. 48.

[18] An Phoblacht 16 July 1926.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Coogan, p. 45.

[21] An Phoblacht 16 July 1926.

[22] Ibid.

[23] An Phoblacht 23 July 1926.

[24] Ibid.

[25] An Phoblacht 30 July 1926.

[26] Ibid, 30 July 1926.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Cormac O’Gráda, ‘Settling In: Dublin’s Jewish Immigrants of a Century Ago’ in Field Day Review Vol. 1. pp- 87-100.

[30] Ibid-p. 90.

[31] An Phoblacht, 30 July 1926.

[32] Irish Times, July 8, 1926.

[33] Irish Times July 15, 1926.

[34] Irish Times August 14, 1926.

[35] Irish Times, October 30, 1926.

[36] Ibid.

[37] An Phoblacht, August 20, 1926.

[38] An Phoblacht, August 27, 1926.

[39] An Phoblacht, October 22, 1926.