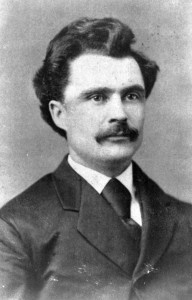

John Boyle O’Reilly and the 1870 Fenian Invasion Of Canada

In the second piece on John Boyle O’Reilly, Ian Kenneally looks some more at Boyle O’Reilly’s role during the invasion of Canada in 1870.

In the second piece on John Boyle O’Reilly, Ian Kenneally looks some more at Boyle O’Reilly’s role during the invasion of Canada in 1870.

The Fenian Brotherhood had been bitterly divided before the 1866 invasion of Canada; a fact which fatally comprised their slim hopes of success. The 1870 Fenian convention took place amid yet more in-fighting. What had been the Roberts Wing had now ruptured into two groups; one in support of John O’Neill; the other opposed to O’Neill.

Consequently, only around 200 delegates attended the convention but it resulted in a resolution to launch another raid into Canada. The Fenian force would be commanded by O’Neill and its goal was to capture two small towns on the Canadian side of border, in the hope that this success would lead to a larger confrontation.

The journalist and Fenian John Boyle O’Reilly, who would write some of the most detailed accounts of the invasion, joined with the Fenian force on 25 May 1870. O’Neill, as general, mustered his men near the town of Franklin, Vermont, a few miles south of the Canadian border.

The Fenians had been bitterly divided over the 1866 invasion of Canda and were even more so over the 1870 venture.

His army consisted of 400 Fenians (there were hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Fenians in the locality but O’Neill had weapons for only a fraction of the men). Typically, the Fenians had been infiltrated by British agents. Consequently, the Canadians had prior knowledge of the Fenian’s plans. This was unknown to O’Neill as he marched his men, whom he called the ‘advance guard of the Irish American army for the liberation of Ireland’ towards Canada. The Fenians crossed the border around noon at which point they came under fire from Canadian militia units, many of them located on a high point called Eccles Hill. O’Reilly was at the front and from his reports it is possible to piece together a brief account of the skirmishing.

In the first discharge of fire one Fenian was killed. The Fenians returned fire but were pushed back to a farmhouse where a Fenian reserve force of fifty men was stationed.

According to O’Reilly, O’Neill intended to make a flanking move around the Canadian right and advance on a village a few miles to the west of their current position. However, the Canadians on the hill opened fire to prevent this. In the first discharge of fire one Fenian was killed. The Fenians returned fire but were pushed back to a farmhouse where a Fenian reserve force of fifty men was stationed. The Fenians made a number of attempts to advance from the farmhouse against the Canadians but suffered a steady drip of casualties.

This engagement continued for a couple of hours but the inability of the Fenians to dislodge the Canadians proved the deciding factor. General O’Neill made a vain attempt to rally his men and lead them on a bayonet charge up the hill. This, almost certainly, would have proved suicidal and O’Neill was forced to concede to the wishes of his men and retreat.

Once back on American soil O’Neill found that he had a new foe. The sitting US President, Ulysses S. Grant, had become fearful that, if his government was seen to do nothing while an attack was launched from US territory, then the relationship between the United States and the British Dominion of Canada could be irreparably damaged. He therefore had issued an order allowing for the arrest of any Fenian violating Canadian territory.

Remarkably, before O’Neill was taken into custody he placed O’Reilly in command of the Fenian army. Although O’Reilly may have supported the idea of an invasion, there is no evidence to suggest that he had been involved in its planning. Once in command he had little impact upon events.

Although fresh Fenian troops were still arriving at the invasion point it is hard to see how O’Reilly could have succeeded where O’Neill had failed. Even if O’Reilly had been able to motivate the troops it was not long before he too was arrested. O’Reilly, along with most of the arrested Fenians, was released soon after. O’Neill would be pardoned by President Grant a few months later.

During the fighting four Fenians had been killed (another would die of his wounds). The Canadians suffered no casualties. Some desultory skirmishing began on the next day but this soon came to a halt.

The affair was a crushing blow to Fenianism in the United States.

The whole affair was a crushing blow to Fenianism in the United States. John Boyle O’Reilly, who had suffered imprisonment in Ireland, England and Australia because of his Fenian activities, gave voice to the dismay felt by many of the participants. After the failure of the invasion the bulk of the Fenians, he wrote, were ‘sadder and wiser men’.

He was particularly upset by the factionalism that rendered the Fenians incapable of united action as well as the condemnation which many American newspapers poured upon the whole Irish community. His paper, The Pilot, would launch a series of editorials attacking O’Neill and other Fenian leaders: ‘The men who framed and executed this last abortion of war-making have proved themselves to be criminally incompetent.’ Fenianism within the United States had been shattered. Its place would soon be taken by a new revolutionary group, Clan na Gael.

Ian Kenneally

From The Earth, A Cry: the story of John Boyle O’Reilly is published by The Collins Press