Book Review: Sleep Soldier Sleep

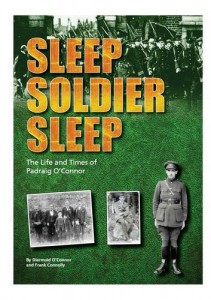

Sleep Soldier Sleep – The Life and Times of Padraig O’Connor

Sleep Soldier Sleep – The Life and Times of Padraig O’Connor

By Diarmuid O’Connor and Frank Connolly

Miseab Publications 2011

Reviewer: John Dorney

Historical memory tends to move in human generations.

As major events happen, at first they are lived experience, shared by most people. After roughly twenty years, they fall out of this category into the near past. Young people will not have lived through the events of which they will either be constantly reminded or else told to forget by the older generation.

As the last of the revolutionary generation pass away, their personal papers are forming the basis for a new history of 1916-23

Commonly, at this point we find some sort of ‘official history’, a standard narrative accepted by those who experienced events. It is only when the generation who experienced events at first hand begins to die off – after about fifty years – that the version they have constructed as memory begins to be re-examined – often critically and with great controversy as the official memory is challenged when set against some of the more awkward recovered historical facts.

In Ireland we are currently living through a fourth phase. The last of the veterans of the Irish revolution from 1916-23 died in the last decade. The storms of controversy over ‘revisionist’ history – was the War of Independence a sectarian campaign? Was British rule benign and resistance to it irrational? Was the republican opposition to the Anglo-Treaty a kind of anti-democratic proto-fascism? – have been and gone. If not settled, such debates are at least less heated. At the same time there has been an enormous release of evidence in the last ten years about the period.

Some of this is official, the Bureau of Military History records for instance have been released, shortly to be followed by the military pension records. But another large part of new evidence is by families themselves who have discovered reams of personal letters, diaries and papers by veterans of the revolution. What all this new evidence tends to do is to restore the messy and contradictory humanity to the events and people that founded the Irish state.

I myself was involved in a project with the Galligan family recently in forging the papers of Paul Galligan (OC Cavan IRA) into a book which will hopefully be published later this year. Kieran Glennon, who wrote a very powerful piece on the Drumboe executions for the Irish Story is engaged in a similar project on his grandfather Tom Glennon of the Belfast IRA and later the National Army.

‘Sleep Soldier Sleep’, is a similar venture – a labour of love by Diarmuid O’Connor in charting the revolutionary career of his uncle Padraig O’Connor – who witnessed the Easter Rising as a teenager, served in the Dublin IRA Active Service Unit and finally in the Dublin Guard – the crack troops of the Free State in the civil war. It was co-written by journalist Frank Connolly.

Padraig or Paddy O’Connor certainly was a fascinating character and this short biography gives the reader a unique ground level view into the heart of the revolution.

The O’Connors were railway workers from Kildare who moved toDublinin the early 1910s. They were also Gaelic League activists and Paddy’s father Sean was a part-time Irish language teacher, member of the IRB and of the Irish Volunteers.

Padraig O’Connor witnessed the Easter Rising as a teenager and was in the heart of the fighting in both the War of Independence and Civil War

In 1916, with the Kildare Volunteers prevented by British cordons from entering Dublin to join in the insurrection raging in the city, the teenage Paddy and a friend crept into the heart of the fighting. Rebel officers and British troops told them to go home but O’Connor left a vivid picture of a hellish urban battle, with bodies scattered on the streets, lit up by burning buildings.

In the War of Independence, O’Connor’s father Sean was interned by the British. His sister hid and fed IRA fighters on the run and stored their ammunition, but Paddy himself became one of the few fulltime soldiers in the IRA – a leader of a section of the Active Service Unit set up by Michael Collins himself, operating out of Inchicore – at that time on the fringe of the city.

The glimpses of the urban guerrilla struggle are in some ways chilling. O’Connor and his comrades, all in their early twenties, bombed a bicycle patrol of RIC men. They shot up military patrols leaving barracks, they assassinated when ordered to do so. On one occasion, Paddy O’Connor was involved in a gun attack on British Army cricket match in Trinity College in which a young woman spectator was inadvertently shot dead. In the IRA attack on the Customs House they provided covering fire to allow those who burned the building to get away. The conflict was also chaotic. Some of what appeared to be IRA operations were pot shots at troops taken by teenagers who got their hands on IRA weapons.

We might have expected Paddy O’Connor to be one of those hardline IRA veterans who opposed the Treaty. He seems to fit the profile – young, hardened to guerrilla warfare, working class (his father headed a left-wing Republican Workers Group in Dublin). But instead he followed his chief, Michael Collins into support for the Free State. It was not an easy decision though. He later told Ernie O’Malley that he made up his mind only the night before the Four Courts was attacked and the civil war begun. His sister was anti-Treaty and had to leave the country. His father Sean also disliked the settlement but went along with his son’s decision.

The Civil War chapters are in some ways the most interesting. O’Connor may have been reluctant to fight former comrades but he was nevertheless involved in surprisingly intense combat. He stormed the Four Courts and was very nearly blasted to smithereens by the explosion which destroyed it. In attacking the anti-Treaty positions on O’Connell Street, he and his men hacked through walls of adjoining terraces, lobbing grenades at republican fighters coming the other way.

In assaulting Tipperary town he refused to use artillery in order to prevent civilian casualties and instead led his troops in an assault on the town. When Erskine Childers the republican head of propaganda was sentenced to execution by theFree State in November, it was again to O’Connor that the Provisional government turned to command the firing party.

Even less than Republicans,Free State troops hardly ever wanted to discuss the civil war afterwards, which makes O’Connor’s conversations with anti-Treaty leader Ernie O’Malley, written down in the 1930s all the more fascinating. The Free State’s executions for him were explained by the government’s weakness. By December 1922, “we were losing the support of the people, our men were war-weary and the going was too heavy for us. Our men had no grub, no uniforms and no pay, so don’t think all the idealism was on your side…The executions broke your morale, there is no doubt about that.”

This from a man who had, as an IRA guerrilla in 1920, broken O’Malley out of Mountjoy prison and saved him from execution at the hands of the British. Real life is hardly ever neat and tidy. It just happens.

There are some drawbacks to this book. The footnoting is somewhat sparse and there is no index. But I can heartily recommend this book to people interested in the ground-level experience of the Irish revolution. It is not yet in the shops (though hopefully will be soon). In the meantime, anyone interested can contact Diarmuid directly at [email protected] to pick up a copy.