An Irishman in Exile, Florence MacCarthy in London, 1601-1640.

John Dorney writes of Gaelic aristocrat Florence MacCarthy’s imprisonment and the Anglicisation of Munster. 1601-1640. You can read about Florence MacCarthy’s life and times here.

John Dorney writes of Gaelic aristocrat Florence MacCarthy’s imprisonment and the Anglicisation of Munster. 1601-1640. You can read about Florence MacCarthy’s life and times here.

Just before the battle of Kinsale in 1601,Florence MacCarthy (or Fionain MacCarthaigh), the last MacCarthy Mor chieftain was arrested by George Carew, the English Lord President of Munster.

The Annals Four Masters tell us

‘Fineen, son of Donough MacCarthy (who was at this time called MacCarthy Mór), went before the President at Cork; but as soon as he had arrived in the town he was made a prisoner for the Queen; but Fineen began to declare aloud, and without reserve, that he had been taken against the word and protection. This was of no avail to him; for he and James, the son of Thomas, were sent to England in the month of August, and … it was ordered that they be shewn the Tower … from that forward to the time of their deaths, … according to the will of God and of their Sovereign’.[1]

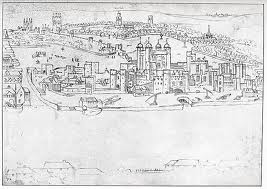

In the early 2000s the Irish language scholar Con Buttimer, found carved into the wall of St Martin’s Tower in the Towerof London, (translated from Irish), “McCarthy, Finain, son of Donagh was put here on the 26th of August 1601, without cause or reason having been captured by treachery. And he was released on…”[2]

The inscription was never finished. MacCarthy never returned to his native Munster.

In fact Florence MacCarthy’s spent the years from 1601 to 1640 in varying degrees of imprisonment inLondon, lobbying for some restoration of the lands he had held in Munster. The years of Florence’s imprisonment were also the decades in which the project of Anglicising Munster, long planned by the English, finally came to fruition

The fortunes of Florence MacCarthy and his sept and clansmen can show how the native elite fared in the first half of the seventeenth century and how they adapted to the new order. While Florence was in exile, his patrimony in Desmond and Carberry was dismembered piecemeal by various indigenous and colonial parties. The independent military power of the Irish lords was largely abolished, although ethnic and religious differences did not disappear.

The End of the War and English Policy in the Aftermath of Florence’s Arrest.

George Carew arrested Florence with one eye on the future. The Nine Years War in Munster had, all but petered out by that time and the President himself said that such was his control over Munster that he could be, ‘a Tamerlane amongst them’, but he saw no need for extreme measures.[3] Florence MacCarthy had tried to maintain a neutral stance in the conflict and had fought both English and rebel troops who had entered his lordship.

However, to have had Florence MacCarthy ensconced in the rugged terrain of Desmond, with thousands of armed followers and occupying vast swathes of land, would have been as serious obstacle to the reconstitution of the English plantation.

In the immediate aftermath of his arrest, Carew and Cecil gave orders for Nicholas Browne and his family, Englishmen who had been expelled in the course of the rebellion, to be re-established into the lordship of Desmond.[4] Carew in particular was very keen to see the English settlers return as quickly as possible.[5]

The MacCarthy Mor lands were also divided up among Florence’s internal enemies, among them his half-brother Donal and his estranged wife Ellen. Donal ‘the bastard’ MacCarthy had fought English troops and settlers for over a decade by 1601. But after he had submitted for the second time, he recovered the land he had held before the rebellion.[6] Carew was careful to stipulate that Donal was not to be given superiority over his ‘freeholders’ (dependants) and to hold his own land by English tenure and not as chief of his sept by tanistry (or election among the high born), as was Gaelic custom.[7]

Ellen MacCarthy, Florence’s wife, who, ‘hath ever understood and repugned the undutiful courses of her husband’ was also designated for a grant of land and money.[8] In addition, several English soldiers were recommended for land grants in Carberry.[9] (For more on Ellen MacCarthy’s, tenacious defence of her interests against her husband, see here)

This can be seen as Carew’s successful dissipation of the MacCarthy Mór lordship – The culmination of English plans to disarm and break up Gaelic lordships and to convert their leaders into simple landlords – a process that would gather pace as the seventeenth century went on. Donal MacCarthy Reagh, a MacCarthy sub-lord, was formally released from his bond to Florence to keep Carberry intact by a surrender-and-regrant deal with Carew in 1606.

Another indication that post-war Munsterwould be fundamentally different from what went before is Carew’s abolition of the lord’s right to private violence. For instance, in late 1600, a small dependent sept of the Muskerry MacCarthys named the O’Learys fought a stiff skirmish over stolen cattle with Dermot Moyle MacCarthy and the O’Mahons of Carberry which left 10 of the O’Learys dead. Cormac MacDermot of Muskerry, their overlord, petitioned Carew to be allowed to take revenge on the Carberry MacCarthys, but Carew refused to allow it.[10] In future, the forces of the state would have a monopoly on legitimate violence in Munster.

While George Carew was attempting to re-make Munster into a new England,Florence MacCarthy, in London, raged against his imprisonment.

Florence MacCarthy tried to ensure his release by offering to help the English militarily

Initially he tried to use the last years of the Nine Years War, in which Hugh O’Neill was hunted through central Ulster, to try to gain some leverage with the government. He claimed to have been impecably loyal during the rebellion, dealing with the rebels only to ‘reclaim’ them or to defend his countries. The authorities however, had no intention of releasing him. Robert Cecil, the Chief Secretary, in forwarding the letter to Carew remarked that he sent them only, ‘because you may see how probably the witty knave can argue’.

Florence offered the services of his foster brother Murrough na Mart (Murrough of the Beef – commander of his ‘foot-men’) against the rebels. He also offered to help to persuade the Ulster forces to surrender by sending, ‘those that are best learned in that language and of special trust, credit and authority’- priests and poets. Florence recommended using his poets (the O’Dalys), since priests, ‘are by no means to be trusted with service to Her Majesty’. He finished by warning of a further Spanish expedition and expressing the hope that he could play the same part in O’Neill’s downfall as he had in the ‘cutting off’ of the arch-traitor Desmond.[11] By now, however,Florence’s intriguing was neither heeded nor acted upon by the English authorities.

Carew’s English troops remained quartered in Munsterfor some time afterwards, disrupting local life. Lord Barry wrote to Cecil in 1604 hoping for, ‘a reformation of the extortions of government troops, soldiers, sheriffs and cessors, who do altogether impoverish this poor kingdom and commonwealth’.[12]

The war had ended in 1603, with O’Neill’s surrender at Mellifont on March 30th. Tensions, particularly sectarian tensions, remained, however, in Munster. In 1603, the townsmen of Cork and other Munster towns expelled government officials and Protestant clergy and called for public toleration of the Catholic religion[13]. Thomond in 1607 wrote that ‘both town and country’ were, ‘altogether ruled’ by priests and Jesuits. ‘I never saw them [the people] unsweeter or more obstinate than they are now’[14]. Although Florence was involved in a marginal way in some Irish Catholic intrigues inLondon, he was to be largely removed from the confessional politics of the new century.

Florence’s imprisonment and life in London.

Florence himself was committed to the Tower with James Fitzthomas – erstwhile leader of the rebel forces in Munster. Cecil found that MacCarthy had ‘protection’ for all of his known crimes and therefore, ‘we must only make him a prisoner by discretion’.[15] In other words,Florence would be held indefinitely without charge, and therefore could be held as long as the authorities felt was necessary. Although the terms of his imprisonment were relaxed over the years,Florence would never return to Ireland.

Records of the Tower show that by St Micheal’s Day 1602, Florence’s health had already broken, as he was provided with, ‘a doctor and one to attend him in his sickness’. Fitzthomas appears to have had some kind of nervous breakdown in imprisonment, as he was afforded, ‘a watcher with him in his lunacy’.[16] The two men were treated reasonably well however, Florence, for example was given food, clothes and a barber, to the cost of £33 a year.[17]

In 1604, the two were transferred to the prison at Gatehouse, Marshalsea which was an easing of his conditions of imprisonment.[18]. Nevertheless, Florence constantly referred to the debilitating effect that prison had on his health. Florence brought up his four sons in London, presumably with the help of his retainers there, although his eldest son died there not long after Florence’s arrest.[19] His estrangement from his wife however was final. In 1607 he reported that he had sent away, ‘that wicked woman that was my wife…whom I saw not nor could abide in almost a year before my commitment’[20].

In the early years of his imprisonment, Florence continued to rail against his arrest while under protection. For example in a letter to Salisbury in 1608, he fumed, ‘all the most suspected persons of Ireland were here at liberty and freely in their countries’, unlike him, ‘none was ever tossed thrice to the tower and restrained seven years, without so much [proof] as might bring him once to be questioned withal!’.[21] However, such important figures as the Earl of Thomond, George Carew and Roger Boyle all lobbied against his release, even on bond to live in London. Florence was thus reduced to asking for, ‘the preservation of my life by…my removing to some other prison, where I may live among men in the hope that my health be recovered’.[22]

After several years, Florence’s imprisonment was reduced to confinement in London but he was re-arrested whenever there were rumours of Catholic plots in the city.

As the years of peace in Irelandwent on though, attitudes to Florence MacCarthy softened, even among his former enemies. He was freed from prison to live in London in July 1614, on bonds of, among others, Thomond, Clanrickarde, Lord Delvin[23] and Randall MacDonnell – showing incidentally how well connected Florence MacCarthy still was with the highest level of the Irish aristocracy.[24]

He was briefly re-arrested in 1617 on the evidence of his servant Teig O’Hurley – a Protestant convert, who testified that he had kept a correspondence with Catholic activist Jacques de Franshesci and had helped transport Lord Maguire and several Irish Catholic priests to continental Europe.[25] The testimony also shows that Florence had seven Irishmen employed in his service in London, all but one of whom were natives of Carberry or Desmond.[26] Florence was briefly rearrested in November 1619, after charges against him from Barry, but was released into London again the following month. He was imprisoned for the last time for a few months in late 1624 and early 1625 after the death of Thomond, his chief bond holder.[27]

Land Disputes. The legal wrangling over MacCarthy Estates.

Florence MacCarthy spent the greater part of his last forty years trying to prevent the loss of his remaining estates to various local lords, both planter and native. As early as march 1604, Barry, an old enemy of Florence MacCarthy, was petitioning to take over the lands of Finian MacOwen and Dermot Meah MacCarthy in Carberry.[28] De Courcy, (another native) wanted to be possessed of the castle and Head of Kinsale, which Florence’s father had bought off his family and which Florence had been leasing to the English undertaker Pelham[29].

Florence claimed that he had legal title to both pieces of land, in Carberry by the overlordship of the MacCarthy Reagh sept, and in Kinsale by legal purchase. Roger Boyle, the new Earl of Cork was also intriguing to take over Kinelmeaky in O’Mahon’s country. In fact, Florenceblamed the Boyle and Browne families, who ‘coveted his lands’, for his continued imprisonment.[30]

In 1611, Florence made a vain attempt at recovering some of the Carberry territory off Donal MacCarthy Reagh, who was possessed of it by a surrender and regrant deal. Florence argued that since it was the common property of the sept, it should be distributed among them and not given to one man. However, he himself implicitly acknowledged that his argument belonged to another era, as there were now many English freeholders and tenants in Carberry.[31]

In Florence’s absence, his lands were divided up among his enemies, English and Irish

Up to around 1617, most of Florence’s land suits went against him. However, in that year, he had his first success since the Nine Years War. He argued that some of the land held by Donal MacCarthy in Desmond had been unlawfully seized by the late Earl of Clancarthy’s tenants and should therefore be returned to him, the heir[32]. The Privy Council agreed and wrote to the Lord Deputy to find in his favour[33].

Still more surprisingly, in 1630, the land originally mortgaged by the English settlers the Brownes from Donal MacCarthy Mór (Florence’s father) was returned to Florence and his heirs.[34] The increasing mildness of government policy towardsFlorence probably reflects the fact that he was no longer a credible threat to the English settlement in Munster. Giving a few estates to the family of a one time aspirant MacCarthy Mór was no longer the risk it had once been.

On the whole though, these years show the dismemberment of the former MacCarthy clan lands in Desmond and Carberry. Not only were the lands divided among the fine, or taken by other lords, they were also settled by English migrants of lower social origin, who became freeholders there in their own right. This change at lower level would have done more than anything else to transform the social character of south Munster.

Florence MacCarthy and History.

Florence MacCarthy was both a writer and a subject of history. In 1609 he wrote a short history of the ‘Irish nation’ to the Earl of Thomond. The piece is interesting in that it shows some of the ideological make-up of the Gaelic aristocrats at a time when their traditional world was collapsing around them.

Florence MacCarthy was both a writer and subject of history

One interesting facet in Florence’s writing is his use of the word ‘nation’. He uses the term to describe a people or ethnic group – the Gaels in this case – not a state or political grouping. The Gaels of Scotland are therefore, ‘our nation in Scotland’.[35] At the time, in Ireland itself, writers such as Goeffrey Keating were forging a new Irish identity based primarily on Catholicism. Keating wrote that whoever is born in Ireland should be called Irish’. MacCarthy, the traditionalist, did not share with Keating, Lynch and others, the inclusive definition of ‘Eireannach’ as opposed to Gaeil or Gaill.[36] In fact, he goes out of his way to blame the Norman lords rather than the natives for the wars and rebellions inIreland subsequent to their invasion. This is a little strange considering that Florence was partly of Geraldine descent himself, although it can probably be explained by his own disputes with Barry and De Courcy who were of Norman ancestry.

He does have some other points in common with contemporary Irish writers though. First of all, like Keating and others, he defends the Irish against the charges of incivility, ‘although they [the Irish] are thought by many fitter to be rooted out than suffered to enjoy their lands, they are not so rebellious or dangerous as they are termed by such as covet it’.[37] Furthermore, he glories in the ‘Golden Age’ in Ireland, when the Irish were famed for their ‘good laws’, their trade, their religious houses and their ‘learned men’, who were ‘esteemed’ by the Saxons and all of Europe.[38] Florence blames the Viking invasion for the decline in Irish civilisation and expresses pride in their eventual expulsion by the Irish nobility.

There is perhaps, an echo of his own experience of war in Munsterin his description of the Vikings, ‘that barbarous cruel and covetous nation, whose tyranny was to place lords and petty lords of theirs in every country…[and] had nearly half the goods thereof’.[39] In his attitude to English rule over Ireland, Florence again agrees with other Irish writers. The Irish nobility, he argued, had accepted the sovereignty of Henry II voluntarily to bring peace, which was disturbed not by them but by rebellious Barons –an implicit rejection of the view that the English could distribute the lands of Ireland by right of conquest. Finally, Florence, like poets such as Mac an Bhaird and O Luinin, celebrated James Stuart’s Gaelic ancestry.[40] James, ‘whose ancestors may have been Kings over all Ireland, who being the first of our nation that reigned over these three kingdoms, although all sorts are hard to be pleased in this world, nobody can deny him to be just King’.[41]

A New Generation

Florence MacCarthy died in around 1640. His was succeeded by his eldest surviving son Donal or Daniel, who converted to Protestantism and was soon writing to the authorities of alleged Irish Catholic conspiracies in Munster.[42]

An anonymous writer in 1686 wrote of Florence, ‘Of all the MacCarthys, none was ever more famous than…Florence, who was a man of extraordinary stature (being like Saul higher by the head and shoulders than any of his followers) and as great policy with competent courage and as much zeal as anybody for what he falsely imagined to be the true religion, and the liberty of his country… his grandson and heir Charles is to this day owned and styled MacCarthy Mór’.[43]

Ninety years later, the description was repeated, almost verbatim, by Charles Smith, a descendent of Cromwellian settlers. He tells us that Donal na Pipi’s grandson also became a Protestant and was High Sherrif of Cork in 1635.[44] However, the MacCarthy Reaghs as a whole were destroyed along with the most of the native nobility after the Cromwellian conquest. They are mourned along with the rest of the MacCarthy’s in Sean O Chonaill’s poem of 1650, ‘Tuireamh na hEirreann’.[45] As for Florence himself, he was accorded some respect by writers up to the eighteenth century. His memory was subject to a min-revival by Irish literary nationalists of the 19th century[46]. However, by the twentieth century he had slipped back to being a minor footnote in the history of the Nine Years war.

[1] Annals of the Four Masters, p.2263

[2] Buttimer, C. An Irish inscription in the Towrr of London,Cork Historical and Archeological Society, 2002, p214

[3] Carew to Privy Council, August 6th 1601, in McCarthy, Letter Book, p.338

[4] Carew to Cecil, Cecil to Carew, in McCarthy, Letter Book, pp 331-332

[5] MacCarthy Morrough, The Munster Plantation,Oxford 1986, p.136

[6] Carew to Cecil, May 29 1602, in McCarthy, Letter Book,p353, he formally received 5000 acres for himself and his heirs in 1605, ‘for his late services and loyalty’ in McCarthy, Letter Book, p.379.

[7] Carew, Wilbraham and Popham to Privy Council, 2 July 1606, in McCarthy, Letter Book, p.378. He was also required to ‘erect’ 24 new freeholders.

[8] Carew to Cecil, January 31, 1602, McCarthy, Letter Book p356. Ellen was granted 13 quarters of land and £150 a year, which was to be left to her sons, Teig, Donal, Cormac and Finian. in 16 April 1607, McCarthy, Letter Book, p.374,.

[9] Carew to Cecil, 13 August 160, in McCarthy, Letter Book, pp 338-3401 Captain Bostocke, for instance.

[10] Pacata Hibernia Vol. III p. 139 This is especially important if one accepts Michelle O’Riordan’s claim that violence was integral to Gaelic aristocratic identity. See Michelle O’Riordan, The Gaelic Mind and the Collapse of the Gaelic World, (Cork 1990).

[11] Florence to Cecil, August 1602, in McCarthy, Letter Book, pp 359-365

[12] Barry to Cecil, March 2 1604, in McCarthy, Letter Book, p. 374

[13] John McCavitt, The Flight of the Earls, (Dublin 2002), p. 52-54.

[14] Thomond to Salisbury, September 19, 1607, in McCarthy, Letter Book, p.383.

[15] Cecil to Carew, September 10 1601, in McCarthy, Letter Book, p. 342

[16] McCarthy, Letter Book p.344 Fitzthomas died shortly afterwards.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Florence to Salisbury, December 1608 in McCarthy, Letter Book, p.387

[20] Florence to Salisbury, June 1608, in McCarthy, Letter Book, p. 385

[21] Ibid.

[22] Florence to Salisbury, December 1608, in McCarthy, Letter Book, p.388

[23] Delvin, himself suspected of treason in 1608, demanded cast iron guarantees of his life and liberty before surrendering, and cited the case of Florence MacCarthy, who was, ‘imprisoned in the Tower on suspicion only, after he had his pardon’ cited in McCavitt, Flight of the Earls, (Dublin 2002) p.129

[24] Bonds to release Florence MacCarthy, 28 July 1614, in McCarthy, Letter Book, pp 398-399. The total bond was £5000.

[25] Testimony of Teig O’Hurley, March 28, 1617, in McCarthy, Letter Book, pp 403-409.

[26] Ibid.

[27]Florence to Privy Council, November 1619, McCarthy, Letter Book p416. Florence to Privy Council, March 1625, in McCarthy, Letter Book, p.418

[28] Barry to Cecil, March 1604 in McCarthy, Letter Book,p.374

[29] De Courcey to Salisbury, July 24 1607, in McCarthy, Letter Book, p.382

[30] Florence to Salisbury, December 1608, in McCarthy, Letter Book, pp 384-389

[31] Florence to Salisbury, 27 November 1611, in McCarthy, Letter Book, p.395

[32] Florence to Privy Council, April 10, 1617, in McCarthy, Letter Book,p.411

[33] Privy council to Lord Deputy, April 10, 1617, in McCarthy, Letter Book, p.412

[34] Judgement in MacCarthy-Browne case, 1630, in McCarthy, Letter Book,p.431.

[35] John O’Donovan (ed.), ‘Letter of Florence MacCarthy to the Earl of Thomond on the Ancient History of Ireland’, The Journal of the Kilkenny and South East of Ireland Archaeological Society I 1856-57, (Dublin 1858) pp 203-229.

[36] Bernadette Cunningham, The World of Geoffrey Keating, (Dublin 2000), p.109

[37] O’Donovan, Florence MacCarthy to Thomond

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Cunningham, The World of Geoffrey Keating p.126

[41] O’Donovan, Florence MacCarthy to Thomond

[42] Daniel MacCarthy to Dorchester 1630, McCarthy, Letter Book p.437

[43] cited in O’Donovan, Florence MacCarthy to Thomond, This was the son of Daniel MacCarthy who converted to Protestantism.

[44] Charles Smith, The Ancient and Present State of the County of Cork, (Dublin 1774) p.27

[45] Cecil O’Rahilly, Five Seventeenth Century Political Poems, (Dublin 1955), pp 77-78

‘MacCarrtha Mór is a shliocht in aonacht,… is na trí mic rí do bhí fé sin, Tiarna Mór Musgraidhe méithe, is Maccarrtha Riabhach ó Chúl Méin’

[46] Daniel MacCarthy’s Letter Book of Florence McCarthy Reagh is the best example, but see also the chapter, ‘Florence MacCarthy, an Elizabethan Romance’ in M.F Cusack,., A History of City and County of Cork, (Dublin 1875). Standish O’Grady, was scathing about Florence and his contemporaries lack of idealism in his introduction and commentary to the 1896 edition of Pacata Hibernia, a good example of the 19th century tendency to confuse the politics of the present with those of the past.