Book Review: Frontiers of Violence

Book Review: Frontiers of Violence, Conflict and Identity in Ulster and Upper Silesia, 1918-1922.

Book Review: Frontiers of Violence, Conflict and Identity in Ulster and Upper Silesia, 1918-1922.

By T.K Wilson, Oxford 2010

Reviewer: John Dorney

Irish history often suffers from viewing itself entirely in its own terms, without reference to events elsewhere in the world. But comparison shows us more clearly what is different about Ireland and what is similar to other parts of the world.

This book is a fascinating comparison of communal conflict in two borderlands in Europe in the aftermath of the First World War and has much to say about the character of nationalist and ethnic conflict.

Comparative conflicts

One is Ulster, the northern Irish province, where 714 people according toWilson’s figures, lost their lives in political violence involving the IRA, Crown Forces, loyalist paramilitaries and on many occasions, rival Protestant and Catholic street mobs, between 1920 and 1922. The question at stake was whether the north would follow the rest of Ireland into secession from the United Kingdom.

Unlike the rest of Ireland, in Ulster most casualties were caused not in confrontation between the IRA and Crown forces but in violence between Catholics and Protestants. As most Irish readers will be aware, the province was partitioned (first in 1920 and definitively in 1922), with three majority Catholic counties ending up in the Irish Free State and the remaining six staying in the United Kingdom as Northern Ireland.

In Ulster, catholics and Protestants vied for inclusion in Irleand or Britain. In Upper Silesia, Polish and German speakers fought over inclusion into Poland or Germany

The other case is the province of Upper Silesia, on the border between a defeated Germany and a resurrected Poland at the end of the World War. Here 2,824 people were killed in a conflict between German and Polish nationalists in a dispute over the plebiscite which would decide the fate of the province in 1921. The vote of the province was, by just under 60-40 to stay part of Germany, however an insurrection (the last of three since 1918) by Polish nationalists secured Poland about a quarter of Upper Silesia and much of its heavy industry.

The casualties in Upper Silesia were, allowing for population, about 3 times higher than in Ulster. Moreover, there was greater use of ‘transgressive violence’ there – mutilation of the dead, rape of women and other extreme forms of violence.

Peace by separation?

Why this was is the subject of Wilson’s book. His answer is that in Ulster, social divisions between Catholic and Protestant were all but watertight. They lived, worshipped and were educated separately. Elections were simply a contest in getting out the maximum number of Catholic or Protestant voters or eliminating opposition ‘within’ the community. There was no prospect by and large of getting Catholics to support the Union or of Protestants, as a whole, supporting Irish independence.

Wilson argues that social separation and the long tradition of sectarian violence in Ulster actually limited the violence there.

In Upper Silesia, however, the ethnic difference was linguistic, between speakers of German and Polish and was much more fluid. Not only did people choose one language over the other for all kinds of reasons, most of the population also spoke ‘water Polish’ a Polish dialect with many German words. As such they were much freer than those in Ulster to ‘choose’ their nationality. Families and communities could be divided. No one’s loyalty was sure.

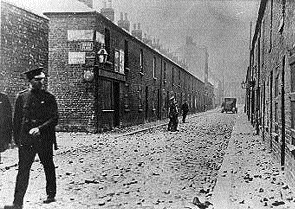

In Ulster therefore, violence to subdue a minority community was more straightforward. Everyone knew they were a potential target and it took relatively little violence to overawe a minority when they did not have the numbers to respond. Where they did it was obvious that they would retaliate against one’s ‘own’ community. Inner city Belfast therefore fought it out savagely until mid 1922 but in many parts of the province both communities – certain of retaliation – worked to restrain the violence.

In Upper Silesia on the other hand, people whose allegiance to one side or the other was uncertain could be terrorized into voting ‘the right way’. Hence the need for extreme violence. Those who did rape and mutilate the dead could also do it relatively free of the certainty of reprisal in kind that would have occurred in the north of Ireland. Also, whereas in Ulster violence broke out at clear flashpoints, west Belfast and the village of Roslea for instance, in the German-Polish borderland it could break out anywhere – in pubs, in the street, at weddings.

It is an intriguing argument and deserves consideration. In rural Cavan (which this reviewer has studied from a republican perspective) for instance the UVF had several thousand members and over 1,000 rifles but it took only some desultory raiding by the IRA to disarm and effectively neutralize them. Protestants were less than 20% of the county’s population and appeared to accept after partition that the numbers were against them and nothing could be done to change the political situation.

Another fascinating thought is that openly sectarian Irish nationalists such as the Hibernians (who did not admit Protestants) were less of threat to Protestant unionists than the ostensibly non-sectarian Sinn Fein and Volunteers/IRA who refused to respect the sectarian headcount inUlster. This again is borne out by looking at County Cavan, where in 1918 republicans complained that to campaign for election they had to physically fight both Hibernians and Orangemen together in riots.

Ireland in a wider context

I am not qualified to judge whether Wilson’s analysis holds true for Upper Silesia or other ethnic borderlands in Europe or whether his contention that religious-national cleavages are ‘harder’ boundaries than linguistic-national ones is valid. However I suspect this generalization should not be taken too far. In pre-WWI Slovenia for instance, a memoir (Martin Pollack’s The Dead Man in the Bunker) tells of a society utterly divided, Ulster-style by language between Germans and Slovenes, with no social interaction across the divide despite a shared religion. In Bosnia, where Serbs, Croats and Bosniaks are defined solely by religion, inter-marriage was high in postwar Yugoslavia and it took a vicious war to separate them into marked out communities in the 1990s.

Ulster may have been less violent than Upper Silesia but all of Ireland was not

This book is not a survey of either the Irish or Silesian conflict but rather a comparative analysis. The reader will have to look elsewhere to find out what actually happened in these two conflicts at either end of Europe.

Wilson may also have taken his theory on the why Upper Silesia was bloodier a little too far. For instance if all of Ireland is included from 1916 to 1923, the death toll rises to some 5,000 people. Moreover as he acknowledges, Upper Silesia’s casualties can also be explained in part by the conventional warfare that erupted between regular German troops and Polish nationalist fighters aided byPoland itself in the three Polish insurrections. With the partial exception of the IRA offensive of May 1922 (secretly endorsed by Michael Collins and the nascent Free State government) hostilities of this scale were not seen in Ulster.

The book is also prohibitively expensive for anyone without access to an academic library – at over 70 euros. (Though you can buy cheaper copies used on Amazon here).

However it is a welcome effort at putting Irish history in a wider context and has many interesting and thought provoking insights.

You can read another review of this book here.