The Postal Strike of 1922

Cathal Brennan tells the story of the Postal strike of September 1922, in which the postal unions struck against pay cuts in the infancy of the Irish Free State and at the height of the Irish Civil War.

The Postal Strike of 1922 was the first major industrial dispute the new government of the Irish Free State faced and it occurred right in the middle of the Civil War.

When the dispute began, the government refused to concede the right of public servants to withdraw their labour and go on strike. The postal workers were condemned for taking industrial action in a difficult economic time when unemployment was high because, as members of the public service, they enjoyed permanent, pensionable positions.

Steps were also taken to restrict the rights of the postal workers to picket peacefully and they were subject to regular harassment from the military. Due to ongoing Civil War, some members of the new government described it as a ‘stab in the back.’

The behaviour of the Government towards the postal strikers challenges the narrative that 1922 was ‘the birth of Irish Democracy,’ and that the Free State side represented legality, tolerance and compromise. In fact, their handling of the postal strike shows them as intolerant of dissent and willing to use harsh measures to suppress it.

The origins of the strike

The dispute was prompted by the threat of the Provisional Government to cut the cost-of-living bonus of civil servants. The bonus was paid in twice yearly instalments and was introduced by the British Government during the First World War because of the dramatic rise in the cost of living. When the war ended, prices continued to rise and the bonuses, calculated as a percentage of the workers’ basic wages, were kept in place. The Board of Trade figures gave the increased cost of living as 130% above the normal. The bonus provided an increase of 130% on the first 35s of Civil Servants’ wages and 60% only upon the remainder.

For the postal workers these bonuses were essential, as in 1891 the maximum amount earned by a postal clerk in Dublin, after seventeen years service, was £2 16s per week. In 1922 it had risen (apart from bonus) to £3 1s – a gain of 5s in over 30 years.[1]

The postal workers felt particularly hard-done-by as other civil servants had seen their basic wages rise considerably during the war.

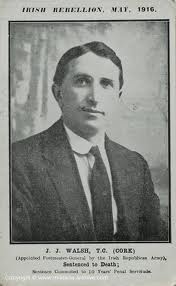

JJ Walsh, the Postmaster General had been a republican readical and trade unionist himself but his first act as Minister was to put cut postal workers’ pay.

The new Provisional Government’s Postmaster General was James Joseph Walsh, the TD for Cork Borough.[2] Walsh was a former postal worker himself, where he had had a reputation as an active trade unionist and ‘advanced nationalist’. Having become a post office sorting clerk and telegraphist by competitive examination at the age of fifteen, he was dismissed from the service in 1914 after writing a public letter to Cork Corporation protesting at the awarding of the freedom of the city to the Lord Lieutenant. A Defence of the Realm order was issued forcing him to reside within the county of Dublin.[3] Early in 1919 he had urged Sinn Féin to, ‘disseminate Bolsheviki [sic] literature to the military in this country,’ so as to provoke unrest throughout the British Army.[4]

During the struggle against the British, the republican movement had indeed benefited greatly from political strikes such as the General Strike against conscription in 1918, stoppages to support hunger strikers in March 1920, and the decisions of railway workers not to transport British soldiers and munitions.

In 1922, however, when Joseph Walsh and his secretary of the department, P.S. O’Hegarty – who was, like Walsh, a Corkman, veteran Sinn Féiner, IRB man and former Post Office worker in London with Michael Collins[5] – found themselves in a position of power in the new, embattled, Irish government and their priorities were very different from when they were revolutionaries.

Walsh later claimed that the Postal Service within the twenty-six counties had been run at a loss of a million and a half pounds in 1921. He acknowledged that many classes in the service were poorly paid, but to effect an improvement, ‘in any considerable number of the thirteen thousand (employees) we inherited would have placed a burden on the back of the new State which it would never have been able to bear.’[6]

Walsh and O’Hegarty’s first major act was to cut the pay of postal workers. [7]

The postal employees’ response was swift and defiant. On 19th February a ballot of the GPO staff, clerks, postmen and other employees in Cork resulted in an almost unanimous vote for strike action if the recommended wage cut came into effect on the 1st of March.[8]

Right from the start, Walsh and his colleagues saw the threatened strike as an attempt to sabotage the new state. A copy of a telegram sent by Walsh to his opposite number in London was leaked to the Postal Unions and a handbill entitled ‘Heads Up!’ was distributed. It stated;

Anticipate sectional strike of employees disloyal to Free State on 1st prox. Provisional government determined to dispense with their services and substitute those of hundreds of loyal Irishmen in Great Britain seeking transfer. Would you please take immediate steps to ascertain the number of all ranks prepared to transfer under these conditions? Please acknowledge. Walsh, Postmaster – General.[9]

The suggestion that striking workers be replaced with ‘scabs’ from England caused a great deal of upset. The leader of the Labour Party, Thomas Johnson, wrote to D.R. Hogan of the Irish Postal Union stating that if, ‘any attempt is made to bring men and women from England for the purpose of breaking a strike, should one occur, it will meet with the fiercest hostility from all ranks of Irish Labour. It is undoubtedly a most serious matter for Irish Labour in general that one of the first acts of an Irish Minister should be to ask a British Minister to send scabs to break a strike.’[10]

Walsh called the allegation that he had called for the introduction of English strike breakers into Ireland, ‘an absolutely false and a deliberate perversion.’ He said that he telegram concerned the 400 and 500 applications from Irish men and women in the British Post Office to transfer their jobs to Ireland rather than the importation of English workers.[11]

The idea that if a strike went ahead they would be replaced by Irish, rather than English, strike breakers was however hardly an issue likely to placate Irish postal workers.

The Minster for Labour, Joseph McGrath, threatened to resign over the telegram[12] and it was decided that a repudiation of Walsh’s wire to the English PMG would be made by Michael Collins. McGrath would later repudiate Walsh’s suggestion in the Dail, when questioned by Republican TD Constance Markievicz.[13]

Attempts at Arbitration

In the short term, the strike was averted.

The strike was avoided in February but only put off until September 1922

Three government Ministers, J.J. Walsh, Joe McGrath (Labour) and Kevin O’Higgins (Home Affairs) met a delegation from the postal unions on 28th of February at University Buildings. After the meeting the Provisional Government issued a statement saying that:

The PG [Provisional Government] stands for the payment of a fair wage to all its employees, but it cannot allow any section to take advantage of the transitional period to endeavour to entrench itself at the expense of the public. Its work at present is to take over the existing departments on behalf of the Irish nation and to supervise their administration until the Irish Free State comes into being.[14]

Agreement was reached between the Provisional Government and the Irish Postal Union at 8 pm on March 5th, a mere four hours before the strike was due to come into effect. They agreed that an independent commission would be set up to inquire into the wages, organisation of work and conditions generally in the Post Office and report by the 15th May.[15]

The Commission of Enquiry into Post Office Wages and Conditions was chaired, at the suggestion of Michael Collins, by Senator James Douglas, a Quaker businessman and a trustee and honorary treasurer of the Irish White Cross (an Irish political prisoners help group) during the War of Independence.’[16][17]

The Commission issued its interim report on 11th May, and advocated a basic wage raise of 12 ½ %, to compensate the workers for the bonus reduction. It stated that, ‘the Post Office staff in Ireland have found it extremely difficult to adjust their living expenses to the reduction in their bonus; that this reduction has caused hardship especially in the case of married men with families.’

The strike begins

However, on the outbreak of civil war on June 28th , when Provisional government troops dislodged the anti-Treaty garrison in the Four Courts, the stakes in the pay dispute were upped dramatically.

The Commission inquiring into postal workers’ pay was suspended when the officials in the Department of Posts and Telegraphs informed the Commission and the Postal Unions that because of the disturbance caused by the Civil War they found it impossible to take further part in the work of that body.[18]

Unbeknown to the unions, and without any agreements, contrary to the terms of the Commission, the Government began preparing its own cost of living figures, in order to justify pay reductions.

When this became public, on 4th September 1922, meetings were held of postal, telegraph and telephone workers in the Ierne Hall, Conarchy’s Hotel and Hughes Hotel respectively to elect delegates to a special conference.

The meetings passed the following resolution, threatening strike action:

‘That the proposed [pay] reduction will force postal workers to a standard of living which they cannot accept, resolved that the National Executive be instructed to resist a reduction by a withdrawal of labour if necessary’.[19]

The special delegate conference of the Irish Postal Union, presided over by John Normoyle, was held the following night in the Round Room of the Mansion House. The civil war fighting prevented delegates attending from some regional centres, ‘but from these places messages were received urging resistance to the “cut.”’[20]

After a prolonged discussion, the resolution adopted at the previous night’s meeting was moved by P.J. MacPhillips of the National Executive and seconded by J. Kelleher from Cork. The resolution was adopted unanimously.

By this time the government was in no state of mind to make concessions. The Department of Home Affairs issued a statement to the press on the coming strike:

The Government does not recognise the right of Civil Servants to strike. In the event of a cessation of work by any section of the staff of the Postal Service, picketing such as is permitted with industrial strikes, will not be allowed. … The Post Office service is a vital State service. The Government is prepared to use, if necessary, all the forces at its disposal to ensure that no official who continues his service to the State will be subjected to interference or intimidation.[21]

Preparations were made to employ ex-postal workers for the duration of the strike and for the Dublin Metropolitan Police to guard postal vans. [22] The Secretary of the Department of Posts and Telegraphs, P.S. O’Hegarty, warned postal workers that they would be sacked if they went on strike and if reinstated afterwards, would lose their pension entitlements. [23]

J.J. Walsh and the strikers

The postal strike led to bad feelings particularly between J.J. Walsh and the postal workers. Walsh, despite being a former postal worker and union member himself, was to prove one of the most intransigent members of the government when it came to dealing with their demands.

The postal strike led to bad feelings particularly between J.J. Walsh and the postal workers. Walsh, despite being a former postal worker and union member himself, was to prove one of the most intransigent members of the government when it came to dealing with their demands.

In his memoir Walsh wrote that,

‘the Post Office staff, which had never dared to say “boo” while the British were here, took strike action before we had time to get into our stride. We could scarcely help feeling aggrieved at what we considered a stab in the back, and in particular, observing that the Postal Workers’ Organisation covered the thirty – two counties, the strike was confined to the twenty – six.’[24]

‘The men who resent this wrecking policy are those who were loyal to this country during the past four or five years. The men who were trying to stampede this big postal organisation into a strike say that for 30 years they have agitated with the English, but they never struck.’ JJ Walsh

The Postmaster General had a curious habit of riling up the postal unions anytime he gave statements or press interviews. In an interview with the Irish Independent on 24th February, Walsh claimed that,

‘… taken as a whole, the men who resent this wrecking policy are those who were loyal to this country during the past four or five years. The men who were trying to stampede this big postal organisation into a strike say that for 30 years they have agitated with the English, but they never struck. They reserved that to the advent of their own Government, who, one of them termed the enemy. If the British Government were still in power, needless to say, there would be no strike.’[25]

Walsh’s accusation, that the postal workers had not supported the republican movement during the War of Independence, was a calculated insult to their patriotism and was deeply resented by the unions. In fact the Postal Unions had joined the general strike called in 1918, to protest against the British Government’s threat to introduce conscription in Ireland, and again in 1920, to demand the release of hunger strikers from Mountjoy Prison in Dublin.[26] Workers’ handbills bitterly reminded Walsh that he would still be in Mountjoy Prison if they had not had the right to strike in March 1920.[27]

The Irish Postal Union retorted to Walsh’s statement, saying that there was,

‘no question of sections or wreckers, or enemies of the Free State. As Mr. Walsh should be aware, the Irish Postal Union has already had its strikes – and they have not been ineffective – at the call of Labour and of nationality. Now they are ‘wreckers’ because they intend to strike to prevent a further reduction of their wages, which, it will be shown, are not what the PMG represents them to be. A further reduction, we maintain, will force us to starvation level.’

The union appealed for the reinstating of he Committee of Inquiry and no pay cuts, promising, ‘and the alleged ‘disloyalty to the Free State’ will disappear… Meanwhile the prospects of Postal peace are seriously jeopardised by Mr. Walsh’s unfounded statements and his attempts to crush us by help from England.’[28]

Another issue calculated to arouse the anger of the strikers was the Government’s decision to raise cabinet ministers’ salaries from £700 to £1,700 a year.

First blood

The dispute began violently, with shots fired at strikers in Dublin. The Provisional government had forbidden picketing and used the Army to stop it.

The strike began at 6 pm on 10th September. At the Telephone Exchange at Crown Alley, Temple Bar, all members stopped work. Only two supervisors were left in the building. According to the report sent to the Strike Committee, when pickets arrived from headquarters, a Captain McAllister approached Mr. Glanville, who was in charge of the picket. He was armed with a revolver and, ‘adopting a menacing tone stated he would allow no pickets to stand about the streets.’[29]

The Government denied the right of postal workers to strike. On the first and second day of the strike, troops fired on pickets and there were over 90 arrests

When Glanville and another striker, Kevlihan, were walking down Crown Alley, McAllister covered them with a rifle and said ‘Get out of this.’ He then turned around and fired at two postmen (Wyatt and Brennan), ‘the bullet entering the wall a few feet over their heads.’ A number of the female operators were assembled on Anglesea Street. While walking towards them, McAllister fired two or three shots in their direction before retreating into Crown Alley Buildings.[30]

In the Dail, TD, Thomas Nagle of Labour castigated the actions of the Government troops, ‘In Crown Alley about 6 o’clock yesterday evening, before the civil police forces—the Civic Guard or the D.M.P.—had notified the pickets they were doing wrong, and even before the pickets knew themselves they were doing wrong, they were fired, upon—although the shots were fired over their heads— by members of the Free State Army.’ Government minister Kevin O’Higgins responded by alleging that the wires and machinery at the telegraph office on Amiens Street had been smashed and the press wires to the Freeman’s Journal and the Irish Independent had been cut. [31]

The next day, 150 union members picketed the postal offices at College Green to fifty and at the Central Telegram Office (C.T.O.) on Amiens Street. At around 11.30 am, ninety pickets were arrested at the C.T.O. by police and brought to Store Street police station. All but four were allowed out, and these men were subsequently released later in the day.[32]

The Dublin Metropolitan Police were told by the Gvoernment that the strike: ‘is not a case in which picketing, peaceful or otherwise, can be permitted’. Picketers were to be, ‘warned of the illegality of their action, and arrests, if necessary, are to be made. Police should use sufficient force to have their directions complied with—if necessary drawn batons. If arms are produced or used by any member of the crowd or any members thereof, then military will take action on being so informed, or on request of the police on duty’.[33]

A DMP Constable, Hogan, was ordered by Inspector Winters to disperse picketers by force if necessary. Hogan refused on the grounds that the order was illegal. Hogan was suspended and then subsequently dismissed by the Commissioner of the DMP.[34]

One DMP constable refused to arrest picketers n the grounds that it was illegal. he was sacked.

At 5pm that evening, the military raided the headquarters of the Telephone Strike Committee in the Moyalta Hotel on Amiens Street. Two Lancia armoured cars, ‘fully loaded with soldiers carrying rifles, revolvers and machine gun equipment,’ pulled up outside and searched the Committee members and their room The officer in charge was described as ‘courteous’ but the committee were informed that they would have to clear out of premises immediately.[35] The Committee later re-established their headquarters at the Carpenters’ Hall on Gloucester Street.

It was clear from the start that military force was to be used against the strikers. To try to avoid more clashes, on 12th September, the Secretary of the General Strike Committee issued a circular to all Sectional Officers in charge of pickets, warning them to, ‘conduct themselves with dignity and restraint while on public processions or on picket duty’ and not to address any remarks to members of the military, the police or members of the public except to tell them that a post office strike was going on. The Central Strike Committee appealed to every member to obey the order, ‘so that we may retain the respect and support of the public in our just fight for a living wage.’[36]

The Dáil debates- ‘The State will preserve itself’

Since the General Election in June 1922, the Provisional Government had repeatedly delayed the assembling of the new Dáil. The Labour Party Deputies had been unanimously mandated by the members of the Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress to resign their seats if the Dáil did not begin sitting by 26th August. The Government reluctantly agreed but then delayed the opening again pleading the special circumstances of Collins’ death.[37] The opening of the Dáil was finally set for 9th September.

In spite of the civil war, the Postal strike was near the top of the agenda. Thomas Johnson, the leader of the Labour Party, asked that Standing Orders could be suspended so that the following motion could be discussed, ‘That the Dáil repudiates the statement issued by the Minister for Home Affairs beginning with the words, “The Government does not recognise the right of Civil Servants to strike.”’[38] Kevin O’Higgins seconded the motion and the debate was scheduled for later that evening.

Johnson opened the debate by declaring that the issue was one of the basic rights of men to combine and to withdraw their labour. Citing, ‘the struggle against the combination laws [which had outlawed early trade unions], the struggle for the right to bargain collectively; the struggle for the right to strike: do they [the government] think that the workers of this country are going to accept the position which places one section of the workers obviously and clearly in the category of slaves?’ He warned the Government, that if they persisted in denying he right to strike, ‘we are going to get up against you every organised worker in Ireland’. [39]

‘We are going to get up against you every organised worker in Ireland’ Thomas Johnson, Labour leader.

Labour TD William Davin reminded the government of, the general strike in 1920 which had seen many members of the Provisional Government released from British custody. ‘You will remember in that particular strike the Postal Workers came out with the rest of organised Irish Labour… The Republican Ministers did not repudiate their right to strike when pretending to govern this country in the interests of the Republican Movement. Therefore, I cannot see any reason now that you have changed your clothes and turned over as Ministers of the Government established under the Provisional Government, why you should adopt an attitude different to that attitude adopted, two or three years ago, when the Postal Workers came out on strike for the release of the Irish Prisoners.’[40]

His Labour colleague, Cathal O’Shannon declared that, ‘all the guns and all the power and all the force in Ireland is not going to make the whole working class in Ireland lie down when the right to strike is challenged.’[41]

Kevin O’Higgins, however the Minister for Home Affairs framed the issue in terms of vital state security;

‘No State, with any regard for its own safety, can admit the right of the servants of the Executive to withdraw their labour at pleasure. They have the right to resign; they have no right to strike. Because of the peculiar position they occupy, they have certain advantages— certain hours, certain tenure, certain pension rights—and every person joining the Civil Service knows well the conditions on which he joins.… The Civil Servant occupies an intermediate position as between the members of an army or police force and industrial workers. In one sense the discipline is not so rigid; in another sense certain recognised rights of industrial workers are denied, and must be denied, if the State will preserve itself.’[42]

O’Higgins reminded the Dáil that with the Civil War still ongoing, the issue of picketing presented a public safety problem and he would not put police or soldiers, ‘in the position that a picket may be used as a screen for the sniper with bomb or rifle or revolver.’ He rather sarcastically commented, ‘The right to strike and the enthusiasm of it was very touching; but members should not be misled by generalities; members must not be misled by emotional talk; members must understand if this State is to be founded, if it is to live and flourish, it must be able to depend on loyal and constant service from its officials.’[43]

‘No State, with any regard for its own safety, can admit the right of the servants of the Executive to withdraw their labour at pleasure. They have the right to resign; they have no right to strike.’ Kevin O’Higgins, Minister

The motion was defeated by 24 votes to 51. The Irish Times commended the motions defeat by stating that, ‘these fifty – one members put the nation’s interest above class interest at some sacrifice – greater or less – of their own feelings… if it (the Government) had surrendered that right, or if parliament had repudiated its policy, the result would have reacted most unfortunately on every aspect of public affairs… it (the country) will be encouraged by yesterday’s vote to believe it has found a Government and Parliament which are inspired with a resolute temper and a high sense of duty to the nation.’[44]

The Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union paper, The Voice of Labour, however, remarked that,

The Government has raised the issue above an ordinary wages dispute – it has raised it to the higher level of the right to strike and the right to picket. It has raised that question of principle by denying the postal workers the common and legal rights of strike and peaceful picket. Now that is an issue which virtually affects the whole Trade Union movement and every Trade Union and Trade Unionist in these countries. It is an issue and a challenge which the Trade Union movement cannot afford to ignore.[45]

The Dáil discussed the strike again on the 13th. Labour TD Cathal O’Shannon wondered, ‘is that the state of affairs to which we in Ireland have come at this day, that this Government and this Parliament finds that the very first act of its Ministry is an act of such a nature… that there is a scrapping of every principle of individual liberty?[46]

In the Dáil debate on the 14th, Professor William Magennis, an independent TD from the National University constituency, seemed to sum up the feelings of many of the postal workers supporters when he stated that, .’

Independent TD, Alfie Byrne, raised the reliability of the Government’s cost of living assessment,

‘the whole of the figures are totally inaccurate, and the reduction in wages, therefore, has been based upon false figures. Why, you would not get a room in a tenement house in Dublin at the present moment at 5s. per week… I say there is no such house to be got in the City of Dublin to-day, and I say that the scale is entirely wrong. Any housekeeper in Dublin, if shown this pamphlet, would tell you that the cost of living is exactly double in some cases the figures quoted in the pamphlet.’[48]

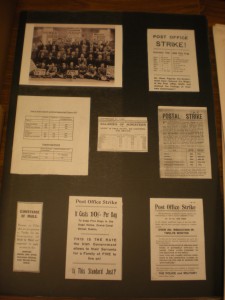

The Strike – September 9th to 29th, 1922

Meanwhile, the strike appeared to be holding firm around the country.

The daily circular to strikers from the Committee described the position in the provinces as ‘leaving nothing to be desired’ and ‘watertight.’ ‘Notwithstanding the Postmaster General’s characteristic ‘bluff’ about a ‘fair service’ being maintained, there is not even a semblance of a skeleton service in any Department of the Post Office.’ The circular urged the strikers that, ‘let the motto now be unity, through suffering if need be, onward to victory.’ [49]

They said that reports arriving from all over the country indicated a complete stoppage of work. The Postmaster General had invited the public to call at the sorting office to collect their letters but, according to the circular, ‘the public forms immense queues, waits for four hours and then leaves with nothing and firms that would normally receive special van loads of mail daily have only received one or two mails since the strike started. The Unions stated that ‘everyone is so disgusted that they are now treating the PMG [Postmaster General]’s statements at their proper valuation.’

The Postal Unions stated that the Automobile Drivers Union had warned all their members not to do any work on behalf of the Post Office and the Transport Workers, the Dockers, Seamen’s and Firemen’s Unions would not handle mails and the Dublin Workers’ Council were organising all classes of Trades Bodies to support the strike.

According to the union, 120 supervising and superintending classes had been suspended along with all the superior officers in the H & D Packet, the Inland TPOs and some men in the Accounts Branch for refusing to scab on the strikers.

‘Everything is plain sailing here. We will have no surrender.’ Ballina strike committee.

The Dublin Evening Mail reported, ‘The Department says that mails are running between this country and Great Britain and that there is an accession of strength to the various services. The statement is no sooner made than it is contradicted from the strikers’ headquarters, who reply rather caustically that the big bags of mails Mr. Walsh claims are being sent to Holyhead are mails being returned that could not be sent down the country’. [50]

The Strike Committee criticised the ‘Die – Hard’ attitude of the Government which, they said, were having the effect of swinging public sympathy more and more on the strikers’ side and, ‘steeling the determination of our members to fight it out to the last.’

They urged strikers to hold meetings as often as possible with speakers from public and trades bodies, without weakening the pickets, and to beware of propaganda, ‘the real truth will be got from our bulletins.’

The Strike Bulletin of the 25th of September announced that the, ‘men’s organisation is perfect, and all attempts to weaken their morale have failed. Meetings are frequently held; every phase of the situation is criticised and discussed.’[51]

After a fortnight on strike, the Joint Executive stated that reports from around the country were positive and that the strike was holding firm. Ennis wrote that the local employment exchange was now offering £1.10.0 a day for strike breakers but there had been no response. Tipperary reported that not a man was at work in their 23 sub–offices. The Longford branch wrote that Longford town and its sub-branches were practically at a standstill. A Government Agent tried to get the mail car running ‘but nothing doing.’ He commended the ITGWU who had contributed £12 towards the relief of distress and were, ‘giving all the support they possibly can.’[52] While Ballina simply stated that, ‘everything is plain sailing here. We will have no surrender.’

The union warned strikers to beware of Government agents who were touring the country using ‘half promises and threats to seduce union members’, and urged them to chase the agents out of their towns, ‘as has already been done in several places.’

It also reported that, ‘a flying column of strike-breakers is the latest effort by the P.O. Dept. to break the postal strike. It is reported that two dozen have arrived in Limerick. It is quite on the cards that the same party will arrive here (Cork) in a day or two to keep up the farce. It reminds one of the stage army which keeps marching to and fro across the stage.’[53]

Elsewhere the Union alleged the government was attempting to recruit temporary postal workers or, ‘juvenile slaves.’ From Dublin schools. [54] It also claimed that one or two notorious former Black and Tans and formerly sacked employees were now in the service of the PMG in Dublin and that Republicans prisoners were offered release if they acted as strike breakers.[55]

Press coverage – ‘An enormous output of propaganda’

After a week of strike action the Dublin Evening Mail felt that it was time for the Government to begin negotiations with the unions to bring the stoppage to an end and complained that: ‘business continues to be dislocated and to a great extent inoperative. …What hope, they say, is there for a settlement when the Postmaster General takes up the attitude that he will not negotiate with the strikers. Meanwhile the long – suffering public just goes on suffering as usual, and is becoming rather sarcastic at the enormous output of propaganda from both sides. “Why don’t they settle it?” says the business man in Dame Street,” instead of arguing about a few points in the cost of living figure. “Commonsense will have to prevail, sooner or later, and why not now?”.’[56]

Newspaper coverage of the strike was to be a constant source of contention with the Strike Committee. Rebuttals were sent to editors almost every day, refuting Government reports that areas around the country were running a normal service and the fact that the newspapers were running these reports as facts without verifying them. Letters from regional branches throughout the country contradicted newspaper reports that mails were running in their area and warned HQ not to be ‘misled by Press’ and dismissed the media coverage as ‘yarns.’ The Kildare strikers wrote ‘official bluff amuses us.’[57]

On 21st September, the Cabinet agreed that the Cost of Living Committee should issue brief statements rebutting the case made by the strikers against the cost of living index figure.[58]

The Evening Telegraph editorial of 21st September appeared to support the strikers’ complaints about the cost of living:If rent and food and necessities of life, not to speak of luxuries, could be procured at the prices quoted by the British and Irish Governments there would have been no Postal or other strike on proposed wages reductions. Until the prices in the shops and in the Government’s returns agree there will always be a fruitful source of industrial strife and unrest….[59]

‘Get out of it or I’ll blow your bloody brains out’

As a result of the Civil War, many police duties were being performed by the National Army. In Dublin relations between the military and strikers were worst. On the 17th of September, one of the most serious incidents during the whole strike occurred at the picket at Crown Alley. One male and three female strikers were picketing outside Merchant’s Arch and were then requested to move on by the military. As they were exiting through Merchant’s Arch onto Wellington Quay a sergeant carrying a revolver fired two shots at them.

As a result of the Civil War, many police duties were being performed by the National Army. In Dublin relations between the military and strikers were worst. On the 17th of September, one of the most serious incidents during the whole strike occurred at the picket at Crown Alley. One male and three female strikers were picketing outside Merchant’s Arch and were then requested to move on by the military. As they were exiting through Merchant’s Arch onto Wellington Quay a sergeant carrying a revolver fired two shots at them.

A worker named Olive Flood was shot but the bullet deflected off her suspender belt and she escaped with a flesh wound in the back of her knee.[60] She was rushed to Jervis Street hospital but released that evening. The correspondent described the provocation for the act as ‘nil’ and wrote that the incident ‘has had no affect whatsoever on the determination of the girls to carry on.’[61]

The Army fired on pickets, beat them with revolver butts and tried to run some over in an armoured car.

The Irish Independent report of the incident stated that the soldier had fired over their heads and that Olive Flood had been injured by a ‘splinter of stone.’[62] which was angrily dismissed by the Strike Committee as military propaganda. [63]

Nor was this the end of the Army’s intimidation of picketers – which led to a stream of angry letters from the union to Army Commander in Chief Richard Mulcahy. The Strike committee complained that, ‘Armoured car AL 14 made repeated attempts to run down pickets at the Rink this evening [25th September]]. Starting from the top of Parnell Square, the car travelled along edge of footpath on the wrong side following picket on to the path. The horn was not even sounded.’[64]

Captain McAllister, commander of the guard at Crown Alley, Temple Bar, who had fired shots at pickets on the first day of the dispute, was reported to have, ‘approached the lady pickets in Merchants’ Arch and said “Get to hell out of it or I’ll blow your bloody brains out.” ’ [65]

Similar altercations were reported in Limerick. The Irish Postal Union Executive received a letter from the Limerick strikers on 27th September stating that when the Enquiry Office was opened at 3 pm the military police sent in one of their members, a Lieutenant Squires, dressed in women’s clothes. When he came out a few minutes carrying a bogus parcel he was approached by one of the pickets. When the picket said ‘there is a strike on’ the officer punched the picket in the face with a knuckleduster.

This appeared to be a signal to the others as the pickets were then attacked by eighteen members of the military in civilian clothes carrying revolvers. No shots were fired but, ‘(revolver) butts were freely used.’[66] According to the strikers, the pickets, male and female, were badly beaten and were threatened by the military that their next picket would be bombed. Half an hour later pickets were again beaten by the military.

One female picketer, Dolly Ryder, was arrested, ‘after getting a good hiding,’ but was subsequently released.[67] The Union was informed that medical certificates outlining the injuries were being collected and would be forwarded to head office. Later that afternoon the same soldiers raided the Strike Committee Offices in the Mechanics’ Institute, removed a large union banner and then smashed up six smaller banners.[68]

On 28th September, the Longford Branch of the Postal union wrote to Head Office to inform them that, ‘The military drew revolvers on pickets on Tuesday, but nothing doing – we still carry on.’[69]

The Army denied the allegations of attacking strikers, replying that, ‘the military under his command had shown the upmost patience under most trying circumstances.’[70]

Negotiations and the end of the strike

On the 25th of September, the same day armoured cars were trying to run over picketers in Dublin, President of the Provisional Government, WT Cosgrave met a deputation from the Irish Trade Union Congress led by Thomas Johnson.

The strike was ended with a reduction of the pay cut and a promise of no sackings.

Cosgrave told the delegation that the Government was not prepared to improve on its pre–strike offer to the postal workers. Richard Foran of the ITGWU warned Cosgrave that they might be pressurised by their members in to sympathetic strikes; ‘20 desperate men might at any time force their hands,’ and transport and railway men were bombarding them to black goods.[71] According to historian Conor Kostick, the Labour leaders’ willingness to restrain solidarity action encouraged the Government to continue the confrontation with the postal unions.[72]

It was Senator Douglas, who had been head of the Committee of Inquiry into postal workers’ pay, who helped bring the dispute to an end through contacts with both the unions and the Government.

According to his memoir, ‘After several conversations with the workers’ representatives I was able to persuade them that the commission would make proposals to deal with their grievances. They agreed to go back if the Government would promise not to take any action of any kind against those who had gone on strike.’[73] Douglas also persuaded the Cabinet them to accept these terms in spite of strong opposition from Walsh who wanted to punish those he saw as the ‘ringleaders.’[74]

On 29th September Strike Headquarters sent a circular to all members. The strike has been declared off on the following terms:

1. 5/8 of the total cut (equivalent to the temporary increase awarded by the Douglas Interim Report) to be retained until December 1st.

2. 3/8 of the total cut (equivalent to the 3/26 Bonus reduction) to take effect from September 1st.

3. The Independent Commission to resume its sittings immediately with substantial guaranteed that the Final report will be issued before December 1st.

In addition to the above terms we have assurances that the Commission’s terms of reference do not preclude the Final Report being made retrospective as from September 1st. All members on strike may resume work on Saturday, the 30th inst., or as soon thereafter as this instruction reaches you.

The Press report of the settlement in today’s papers is an obvious attempt to let the PMG down lightly. It is made to appear that the staff resumed before negotiations commenced, but our instructions to members as to tomorrow’s resumption dispose of that. The Joint Executives are agreed that we have scored a substantial victory. We have won our right to strike, our right to picket and we retain the Douglas award until the Commission shall have finally reported.[75]

Despite the public attitude of the unions, the result of the dispute had been a defeat for the postal workers. The Government had remained resolute throughout and had refused to compromise on its initial offer. They were sending out a clear message that industrial disputes by public servants would not be tolerated.

Epilogue

The claim that there would be no victimisation among the workers was soon broken by Walsh, despite Cosgrave’s assurances to the unions and to the Labour Party.

‘At this critical juncture to smash such a well organised strike was a salutary lesson to that general indiscipline’. JJ Wlash

The union’s spent much of the rest of 1922 and 1923 dealing with appeals by staff who had been dismissed or demoted because they had gone on strike.[76] There was also a great deal of anger towards the Department as workers saw staff who had broken the strike secure promotions. Another issue that the unions felt was particularly vindictive was the Government’s decision to regard the strike as a break in service affecting pension rates and incremental rates. It wasn’t until 1932, and the departure of Cumann na nGaedhal from government, that the incremental pension rates were restored, and a further two years before all the issues regarding pensions were resolved.[77]

In a reply to the Postal Union on these matters, P.S. O’Hegarty wrote that, ‘the PMG must exercise his own discretion as to the officers most suitable for retention.’[78]

In his memoirs, Walsh summed up the feelings of many in the Government when he wrote that, ‘at this critical juncture to smash such a well organised strike was a salutary lesson to that general indiscipline.’[79] The new Government viewed their task as not only wiping out the military threat to the Free State from the Anti–Treaty IRA but also removing the threat to the economic and social order presented by over five years of militant agitation by the rural poor and the urban working class.

A unit of the National Army, the Special Infantry Corps, was dispatched to rural areas in 1923 to quell redistribution of large estates by landless men and the army were also used to suppress workers co–ops and councils.

The Pro–Treaty Government came to be increasingly defined by their opposition to radicalism and were supported by powerful constituencies that demanded determined action by the state to stamp out what they saw as ‘Bolshevism.’[80]

The leadership of the Labour movement in Ireland was not ready to countenance a situation where they would exploit their industrial and political power to challenge the new state at its inception. The Anti–Treaty IRA leadership was also slow to see the potential for their cause that winning the organised workers of Ireland would have given them. One of the few leaders to see this potential was Liam Mellows, who wrote of the postal strike while imprisoned, [81]

The unemployed question is acute. Starvation is facing thousands of people. The official Labour Movement has deserted the people for the flesh-pots of Empire. The Free State government’s attitude towards striking postal workers makes clear what its attitude towards workers generally will be. The situation created by all these must be utilised for the Republic. The position must be defined: FREE STATE – Capitalism and Industrialism -Empire; REPUBLIC – Workers – Labour

Mellows, along with three of his comrades, was executed on the 8th December 1922 as a reprisal for the killing of Pro – Treaty TD, Seán Hales, a shooting that took place five months after Mellows had been imprisoned.

The biggest casualty of the civil war was the labour movement.

It is difficult to argue with Diarmaid Ferriter’s conclusion that while the Civil War divided the country and contaminated public life but that arguably the biggest political casualty was the labour movement. Despite the attainment of a sovereign, independent state (for the twenty – six counties at least) the aspirations contained in Dáil Éireann’s Democratic Programme of 1919 seemed as far away as ever.

Primary Sources

Dáil Éireann, Parliamentary Debates, Vol. 1.

Dublin Evening Mail, 16th September 1922.

Evening Telegraph, 21st September 1922.

Irish Labour History Archive, MS 10 Irish Postal Union, Boxes 1 & 2.

Irish Independent, 20th February 1922

Irish Independent, 24th February 1922

Irish Independent, 25th February 1922.

Irish Independent, 27th February 1922.

Irish Independent, 2nd March 1922.

Irish Independent, 6th March 1922.

Irish Independent, 30th March 1922.

Irish Times, 5th September 1922.

Irish Times, 6th September 1922.

Irish Times, 8th September 1922.

Irish Times, 12th September 1922

National Archive of Ireland, Department of the Taoiseach, NAI D / T S 1798, Labour Disputes.

The Voice of Labour, 16th September 1922.

Secondary Sources

Text of Liam Mellowes’ letters from Mountjoy, http://admin2.7.forumer.com/a/posts.php?topic=9905%20=0&start=105

History Section of Communication Workers’ Union, http://www.cwu.ie/About/History.64.1.aspx (Retrieved 17th March 2011).

Ferriter, Diarmaid, Limits of Liberty, Episode 1 (RTÉ, T.X. 2010).

Garvin, Tom, P.S. O’Hegarty, Dictionary of Irish Biography,(Retrieved 8th March 2011).

Gaughan, J. Anthony, James Green Douglas, Dictionary of Irish Biography, (retrieved 18th March 2011).

Gaughan, Anthony J. (Ed.), Memoirs of Senator James Douglas (Dublin, 1988).

Guilbride, Alexis, An Irishwoman’s Diary, The Irish Times, 18th June 2001.

Guilbride, Alexis, A Scrapping of Every Principle of Individual Liberty, History Ireland, (Vol. 8, No. 4, 2000).

Kostick, Conor, Revolution in Ireland (Cork, 2009).

Maume, Patrick, Sir Thomas Henry Grattan Esmonde, Dictionary of Irish Biography,(Retrieved 8th March 2011).

Maume, Patrick, James Joseph Walsh, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://dib.cambridge.org.elib.tcd.ie/viewReadPage.do?articleId=a8874&searchClicked=clicked&quickadvsearch=yes (Retrieved 8th March 2011).

Murphy, Angela, Luke J. Duffy, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://dib.cambridge.org.elib.tcd.ie/quicksearch.do (Retrieved 8th March 2011).

O’Connor, Emmett, Syndicalism in Ireland 1917 – 1923 (Cork, 1988).

Regan, John M., The Irish Counter Revolution, 1921 – 1936 (Oxford, 1999).

Walsh, J.J., Recollections of a Rebel (Tralee, 1944).

White, Laurence William, Thomas J. O’Connell, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://dib.cambridge.org.elib.tcd.ie/quicksearch.do (Retrieved 8th March 2011).

Footnotes

[1]Irish Independent, 25th February 1922.

[2] Walsh, J.J., Recollections of a Rebel (Tralee, 1944), p. 61.

[3] Maume, Patrick, James Joseph Walsh, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://dib.cambridge.org.elib.tcd.ie/viewReadPage.do?articleId=a8874&searchClicked=clicked&quickadvsearch=yes, (Retrieved 8th March 2011).

[4]Guilbride, Alexis, A Scrapping of Every Principle of Individual Liberty, History Ireland, (Vol. 8, No. 4, 2000), p. 38.

[5] Garvin, Tom, P.S. O’Hegarty, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://dib.cambridge.org.elib.tcd.ie/viewReadPage.do?articleId=a6801&searchClicked=clicked&quickadvsearch=yes (retieved on8th March 2011).

[6] Walsh, J.J., Recollections of a Rebel (Tralee, 1944), p. 62.

[7] Provisional Government Minutes, p. 53, 1st February 1922, NAI, D/T S 1798.

[8] Irish Independent, 20th February 1922.

[9] 28th February 1922, NAI, D/T 1798.

[10] Thos. Johnson to D.R. Hogan, 23rd February 1922, ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 2, Box 2.

[11] Irish Independent, 24th February 2010.

[12] Regan, John M., The Irish Counter Revolution, 1921 – 1936 (Oxford, 1999), p. 93.

[13] Dáil Éireann, Vol. 2, 1st March 1922, Cols. 143 – 144.

[14] Irish Independent, 2nd March 1922.

[15] Irish Independent, 6th March 1922.

[16] Ibid. Alongside him were; Sir Thomas Grattan Esmonde[16], who had been the Irish Parliamentary Party MP for North Wexford up until the 1918 general election, and H.J. Friel (Chairman of Dublin County Council); two nominees from the Labour Party; Luke J. Duffy[16] (General Secretary of the Irish Drapers’ Assistants’ Union) and Thomas J. O’Connell (General Secretary of the Irish National Teachers’ Organisation, and elected Labour Party TD for Galway at the 16th of June 1922 election[16]). Thomas A. Murphy was appointed secretary of the Commission, which first met on 5th March

[17] Irish Independent, 30th March 1922.

[18] ILHA, MS 10, 11, Box 2.

[19] Irish Times, 5th September 1922.

[20]Irish Times, 6th September 1922.

[21] Irish Times, 11th September 1922.

[22] NAI, D/T 1798, 10th September 1922.

[23] Special Notice to All Staff from P.S. O’Hegarty, 6th September 1922, ILHA. (1) An Officer withdrawing his labour, automatically forfeits his position, and (2) In the event of subsequent reinstatement, on settlement , reinstatement would not carry with it restoration of pension rights for the previous service or of continuous service

[24] Walsh, J.J., Recollections of a Rebel (Tralee, 1944), p. 61.

[25] Ibid.

[26] History Section of Communication Workers’ Union, http://www.cwu.ie/About/History.64.1.aspx, 9th March 2011.

[27] Publicity Department Dept., Limerick Joint Postal Committee Sept, 12th 1922, ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 11, Box

[28]Irish Independent, 25th February 1922

[29]th September 1922, ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 11, Box 2.

[30] Ibid

[31] Dáil Éireann, Vol. 1, 11th September 1922, Cols. 109, 110., Col. 113.

[32]th September 1922, ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 11, Box 2.

[33] Quoted by Cathal O’Shannon TD, Dáil Éireann, 13th September 1922, Vol. 1, Cols. 230, 231.

[34] Dáil Éireann, 13th September 1922, Vol. 1, Cols. 231,232.

[35] Telephone Strike HQ to Irish Postal Union, 11 September 1922, ILHA MS 10 IPU, 11, Box 2.

[36]Secretary of Central Strike Committee to Sectional Officers, 12th September 1922, ILHA MS IPU, 11, Box 2.

[37]Revolution in Ireland (Cork, 1999), p. 198.

[38] Dáil Éireann, Vol. 1, 11th September 1922, Col. 108.

[39] Dáil Éireann, Vol. 1, 11th September 1922, Cols. 109, 110.

[40] Ibid, Cols. 121, 122.

[41] Ibid, Cols, 127.

[42] Ibid, Cols. 115, 116.

[43] Ibid, Col. 117.

[44] The Irish Times, 12th September 1922.

[45] The Voice of Labour, 16th September 1922.

[46] Ibid, Cols. 233.

[47] Dáil Éireann, 14th September 1922, Vol 1., Cols. 314, 315.

[48] Dáil Éireann, 13th September 1922, Vol. 1, Cols. 242, 243.

[49] W.J. O’Hara to Irish Postal Union, 14th September 1922, ILHA MS 10 IPU, 11, Box 2.

[50] Dublin Evening Mail, 16th September 1922.

[51] Strike Bulletin, 25th September 1925 (Cork), ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 11, Box 2.

[52] Longford Branch to Central Strike Committee, 26th September 1922, ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 11, Box 2.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid, 3.

[55] Ibid, p. 4

[56] Dublin Evening Mail, 16th September 1922.

[57] 2nd week of stoppage (No date), ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 13, Box 2, p. 2.

[58] Provisional Government Minutes, P.G. 11(a), 21st September 1922.

[59] Evening Telegraph, 21st September 1922.

[60] Telephone Strike HQ to CSC, 17th September 1922, ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 2, Box 1.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Irish Independent, 18th September 1922.

[63] Guilbride, Alexis, A Scrapping of Every Principle of Individual Liberty, History Ireland, (Vol. 8, No. 4, 2000), p. 37

[64] Joint Executive to Richard Mulcahy, 25th of September 1922, ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 13, Box 2.

[65] Joint Executive to Richard Mulcahy, 25th of September 1922, ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 11 – 20, 13, Box 2.

[66] Limerick Strikers to Irish Postal Union, 28th September 1922, ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 13, Box 2.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Secretary to Richard Mulcahy, 25th October 1922, ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 2, Box 1.

[69] Longford Branch to Irish Postal Union, 28th September 1922, ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 13, Box 2.

[70] Captain Padraig Ó Cogáin to Secretary IPWU, 8th November 1922, ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 13, Box 2.

[71] NAI, D / T S 1798.

[72] Kostick, Conor, Revolution in Ireland (Cork, 2009), p. 200.

[73] Gaughan, Anthony J. (Ed.), Memoirs of Senator James Douglas (Dublin, 1988), p. 88.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Joint Executives to all Strikers, 29th September 1922, ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 1, Box 1.

[76] ILHA, MS IPU 10, 15 & 17, Box 2.

[77] Guilbride, Alexis, A Scrapping of Every Principle of Individual Liberty, History Ireland, (Vol. 8, No. 4, 2000), p. 39.

[78] P.S. O’Hegarty to Secretary IPU, 8th November 1922, ILHA, MS 10 IPU, 15, Box 2.

[79] Walsh, J.J., Recollections of a Rebel (Tralee, 1944) p. 63.

[80] O’Connor, Emmet, Syndicalism in Ireland 1917 – 1923 (Cork, 1988) p. 158.

[81] http://admin2.7.forumer.com/a/posts.php?topic=9905%20=0&start=105