Bad form for Bill to discuss badminton for Protestants

Niall Meehan on Protestant sports and southern Irish society

Bill O’Herlihy got in very hot water for observing during RTE’s Olympic Games coverage (29 July 2012) that badminton “was considered a Protestant game”. O’Herlihy’s assertion was roundly condemned as offensive and sectarian in newspapers and on the blogosphere.

The comment was delivered in the blokey style O’Herlihy adopts in quizzing Johnny Giles and Eamon Dunphy on RTÉ’s soccer panel. It seemed out of place in O’Herlihy’s discussion with a female Irish badminton representative, on Chloe Magee’s first round win over her Egyptian opponent. O’Herlihy looked as if he had run out of questions on a sport about which he appeared to know little, apart from the type of person he thought once played it.

Surprisingly, O’Herlihy’s recollection was historically accurate. O’Herlihy committed a gaffe by blurting out sentiments hoped best forgotten. The immediately negative reaction was an illustration of current Irish social psychology. Citizens of the Irish Republic are uncomfortable addressing largely superseded differences between Roman Catholic and Protestant communities and because of that, do not know a lot about them. Besides a fear of reviving vaguely remembered and ill-considered slights and animosities, some view the discussion as itself sectarian. It is a charge difficult to apply to a sports commentator who, though from a Roman Catholic background, is married to a Protestant. The assertion is largely a social-psychological defence mechanism.

Citizens of the Republic are uncomfortable talking about sectarian differences

It is a pity that it is like this. There is an absence of a language within which social, economic and cultural differences, leavened by the vicissitudes of Irish history and politics, may be comfortably explored. Without it, these issues of what Roman Catholics and Protestants did differently in their daily lives, and why, will remain shrouded in embarrassed silences, punctuated by bursts of indignation when the subject is brought up. If anything, the reaction indicates unresolved tensions in society demonstrating the extent of insecurities and inhibitions surrounding the subject.

Let us see if we can unravel some of the inhibitions without upsetting the collective social psyche. How did the inoffensive game of badminton come to be weighed down with a sectarian label?

Surprisingly, it results from an unintended consequence of a strategy initiated within the Church of Ireland to separate in particular Protestant and Roman Catholic young people. But why would they do such a thing?

Mutual segregation

Up to the 1960s the small Protestant community was becoming an even smaller southern minority. ‘Mixed’ marriages under Roman Catholic Ne Temere rules, in which children had to be raised as Roman Catholics, could potentially produce denominational suicide. The Church of Ireland, the largest non Roman Catholic denomination, took steps to create and to maintain a social separation that would encourage marriage within the Protestant community and discourage it with Catholics. The Roman Catholic Church happily accommodated this approach, as it did not want Catholic young people in turn associating much, if at all, with Protestants. It suited both denominations.

However, the arrangement sustained and reinvigorated parallel sectarian social provision in education, health and welfare, in which the biggest confessional organisation, the Roman Catholic Church, was dominant. It helped to promote a separately supportive, occasionally fractious, conservative social structure in southern Ireland. Institutions inherited from pre independence nineteenth Century skirmishing between Protestant and Roman Catholic charitable religious organisations, became the core institutions that substituted for a secularly based welfare, health and education system in the South.

Both Catholic and Protestant Churches preferred their churches, welfare organisations and, yes, sports clubs to be mutually exclusive

For every conservative Catholic organisation or practice, there was probably a Protestant equivalent, but the latter phenomenon is not generally understood. The Protestant evangelical Bethany Home for unmarried mothers came to public notice during the past few years, largely because former residents asserted that they were ignored. Also because of the related discovery of over 200 unmarked graves of Bethany babies in Mount Jerome cemetery in Dublin (see ‘Church & State and the Bethany Home’). Similarities of experience between Catholics and Protestants were expressed by difference, creating separated communities of feeling and outlook. Similar activities were separated by a wall of ignorance and of silence, one Bill O’Herlihy breached momentarily. One inadvertent result has been to see phenomena like child abuse as a particularly Roman Catholic problem and to imagine that bad things did not happen to Protestant children. We now know (and should have known anyway) that that view is flawed. It is possible that the absence of attention paid to Protestant institutions caused abuse to go on there longer, see ‘Inquiry into ‘exploitation’ of orphans’, Irish Times, 17 May 2012 .

Issues such as ill-treatment of unmarried mothers and sectarian recruitment policies were common to both Churches

In the south, besides Protestant schools and hospitals (and “Protestant firms”), at a more informal level were Protestant only employment and marriage bureaus, dances and sporting activities. Martin Maguire has written a very useful article on ‘Our People’, on Church of Ireland communities in Dublin. It begins with commentary on advice to young people to make friends exclusively amongst “our people and within the church community” (available here).

In November 1941 in the Irish Times Rev’d A Hobson of the Church of Ireland in Innishannon, Co Cork, attempted to placate alarmists warning of organisational complacency. The Free State’s larger towns and cities contained, he said,

“hardly a tennis club in the summer time, or a hockey or badminton, or a table tennis club in the winter, or a reading room or a concert, or a lecture or even a dance, which is not run in the closest possible connection with the local parish church”.

Where relationships failed to emerge from these agreeable sporting and musical interchanges, Mrs Brewster’s Dublin Marriage Society was on hand. She advertised in the Irish Times, “opportunities for Protestant professional and business men” (4 March 1953), as well as “C. of I. ladies, county background, to meet gentlemen with farming or professional interests” (2 February 1953). Mrs Brewster also occasionally promoted that she catered for non-Protestants, but emphasised, “separate R.C. and Protestant departments” (ibid) or simply, “religious safeguards” (30 March 1954).

Badminton, a sport apart

And so it continued into the heady 1960s when things gradually fell apart. A Church of Ireland soccer league survived in Dublin into the late 1960s, before better players, fed up with declining standards, abandoned it for non-sectarian soccer. Admission by ticket only to Church of Ireland Dances, policed by the local clergy, were increasingly deserted during the same era, from boredom usually, in favour of showbands, bright lights and the big city.

Badminton was indeed promoted as a social event for Protestants

Badminton, in particular, was organised on a basis of sectarian exclusivity. While soccer was never considered a ‘Protestant game’, being both popular and proletarian (‘foreign’ was the adjective usually attached), badminton attained that distinction. Unlike other sports, some Protestant players promoted it as a specifically Protestant activity.

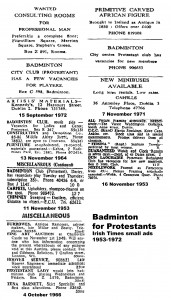

In researching ‘Shorthand for Protestants, sectarian advertising in the Irish Times’ for History Ireland (September 2009, ). I noted Protestant-only badminton clubs advertising for members. These were in Dun Laoghaire, Ranelagh, Dartry and Dublin City, or stated simply ‘southside’ (no ‘northside’, intriguingly, though a Protestant community lived around Drumcondra, though that was mainly working class). No other sport promoted itself in this openly sectarian manner, which is possibly why it stuck in Bill O’Herlihy’s consciousness. Sometimes, aficionados of the shuttlecock might publicise their availability, for example in 1966, “Protestant lady would join badminton club playing Wednesdays and Fridays”. The last I traced was in September 1972, quite prominent amongst the back page personal ads. It said simply, “Badminton City Club (Protestant) has a few vacancies for players”. The accompanying graphic gives examples of the type, of which there were many.

Little public animosity was evident, apart from a letter published in the Irish Times in September 1969, mentioning an RC applicant “refused admission to a Church of Ireland badminton club”. However, that letter noted a new political context, southern Protestants distancing themselves from Northern Ireland unionists claiming a link between Protestantism and Britishness. As the North descended into chaos after 1968, this southern sectarian sporting activity disappeared from view, albeit retained as a dim Bill O’Herlihy memory. Another possibly related reason for its disappearance is that, like many Roman Catholic social practices, sectarian sport was considered out of place in a modernising society with a growing secular consciousness.

So, Bill O’Herlihy was not wrong, just wrong to bring up the subject. People are clearly uncomfortable and embarrassed discussing it. Bill might be better advised in future to bone up instead on the actual game of badminton, until the currently uptight attitude toward discussing who played it abates somewhat.

Niall Meehan is Head of the Journalism & Media Faculty in Griffith College

Further Reading

Maguire, Martin, ‘Our People’ the Church of Ireland and the culture of community in Dublin since Disestablishment. In Gillespie, Raymond & Neely, W. G., eds, The Laity and the Church of Ireland, 1000-2000. Four Courts, 2002, http://eprints.dkit.ie/75/1/Our_People_Laity_of_the_C_of_I.doc.

Meehan, Niall, “Protestants … were left as Orphans”, Church & State, 4th Quarter, 2010, http://gcd.academia.edu/NiallMeehan/Papers/315286

Meehan, Niall, Church & State and the Bethany Home, History Ireland, v.18, n.5, Sep-Oct 2010, http://gcd.academia.edu/NiallMeehan/Papers/277737.

Meehan, Niall, Shorthand for Protestants, Sectarian Advertising in the Irish Times, History Ireland, Sep-Oct 2009, http://gcd.academia.edu/NiallMeehan/Papers/112400.