The Irish War of Independence – A Brief Overview

Continuing with our series of overviews and following the Overview of the Easter Rising and the Overview of the Irish Civil War, John Dorney tells the essential story of the 1919-21 Irish War of Independence.

For more detailed articles on the war see the Irish Story archive on the War of Independence.

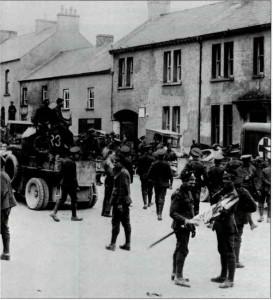

The Irish War of Independence was a guerrilla conflict between the British state and its forces in Ireland and Irish republican guerrillas in the Irish Volunteers or Irish Republican Army. The war is usually said to have run between 1919 and 1921, but violence both preceded these dates and continued afterwards.

Parallel with the military campaign was the political confrontation between the separatist Sinn Fein party, who after winning the General Election of 1918, declared an Irish Republic, and the British administration based in Dublin Castle.

A third strand of the conflict lay in the northern province of Ulster, which was majority unionist or pro-British and which opposed Sinn Fein. This led to violence between the majority Protestant unionists and the mainly Catholic Irish nationalist minority in the north.

Home Rule versus Republic

In 1912, as a result of a political deal between the Irish Parliamentary party and the Liberal Party at Westminster, the British government introduced a Bill for Home Rule, or limited autonomy for Ireland within the United Kingdom as Irish nationalists had been demanding since the 1880s.

However, this was opposed by Ulster Unionists, who formed their own militia, the Ulster Volunteers to oppose Irish self-government. Irish nationalists in response formed a rival militia, the Irish Volunteers to ensure Home Rule was passed. Tensions between the two sides were eased by the outbreak of the First World War, when both sides agreed to support the British war effort.

However, in 1916, a more radical Irish nationalist element in the Irish Volunteers, largely directed by the Irish Republican Brotherhood, unhappy with support for Britain in the war and believing that Home Rule fell too far short of Irish independence, launched an insurrection known as the Easter Rising in Dublin, proclaiming an Irish Republic. See the Easter Rising, an overview.

The rebellion was put down within a week with about 500 deaths, but the British reaction, executing the leaders and arresting 3,000 nationalist activists antagonized Irish public opinion.

However, British policy was inconsistent. In 1916-17, in a bid to restart negotiations on Home Rule, all of the prisoners from the Easter Rising were released. Many of them joined the Sinn Fein party and led a very popular campaign against the introduction of conscription into Ireland for the Great War.

From this point on there were riots and confrontations between Sinn Fein and Irish Volunteer activists and the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and British Army. Several hundred republicans were arrested in 1918 under charges of conspiring with Germany. More were detained under legislation banning public parades.

In December 1918, Sinn Fein decisively won the Irish vote in the General Election taking 73 seats out 105 (being a majority everywhere except Ulster) and declared an Irish Republic. The first republican parliament or Dáil, met in January 1919, though more than half the Sinn Fein members of parliament were imprisoned at the time.

War begins

On the same day that the Dáil first met, two RIC constables were shot dead by Irish Volunteers under Dan Breen at Soloheadbeg in Tipperary and the explosives they were carrying seized. This is commonly presented as the opening shots of the war but there had been deaths in 1918 and only 17 more people were killed in 1919. In Dublin, Michael Collins the Volunteers or IRA Director of Intelligence formed a ‘Squad’ to assassinate detectives who coordinated the arrest of republican activists. Late in the year his men attempted but failed to kill John French, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

Alongside the limited armed campaign there was significant passive resistance including hunger strikes by prisoners (many of whom were released in March 1920) and a boycott by railway workers on carrying British troops. There were also significant disturbances in rural areas as small farmers attempted to seize parts of large ‘ranches’.

Violence intensified in early 1920. Much of the Sinn Fein political leadership had been arrested. Eamon de Valera, the President of the Republic, had gone to America to raise funds. The two leaders of the IRA, Collins and Richard Mulcahy, ordered Volunteer units around the country to raid RIC barracks for arms. Though the Dáil eventually endorsed the IRA’s campaign in 1921, some Sinn Fein figures such as Arthur Griffith disliked the use of violence.

A series of attacks on rural police barracks ensued in early 1920. The RIC withdrew from its smaller stations into fortified barracks in towns and the abandoned posts were systematically burnt by the IRA around the country on the night of Easter Sunday 1920. By the summer of 1920, many RIC men were resigning their commissions and in many localities the IRA were in the ascendant. In other places the RIC responded to attacks on them with assassination of republicans such as Tomas MacCurtain, the Lord mayor of Cork.

At the same time, in the summer of 1920, Sinn Fein won local government elections across most of Ireland and took over functions of government from the state such as tax collection and law enforcement. In some places the RIC was replaced by Irish Republican police and the Court system by the Sinn Fein or Dáil Courts.

To put down this insurgency, the British government under Lloyd George proposed autonomous governments in Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland and also deployed new corps of paramilitary police from Britain, the Black and Tans and Auxiliary Division, made up largely of war veterans from the First World War. Lloyd George also passed the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act, giving special powers to the police and military.

Escalation

This triggered a grave escalation of the conflict as the new forces carried out reprisals on the civilian population for IRA attacks – in the summer of 1920 burning extensive parts of the towns of Balbriggan and Tuam for example. The IRA in response formed full-time Flying Columns (also called Active Service Units), which in some parts of the country became much more ruthless and efficient at guerrilla warfare.

In the north there was severe rioting in Belfast, Derry and in Lisburn after a IRA killing of two northern Protestant police officers in separate incidents, after which loyalists attacked Catholic areas. Up to 100 people were killed and hundreds of Catholic homes burnt out. Another 7,000 Catholics were expelled from their jobs in the Belfast shipyards. The Northern Ireland authorities also formed the Ulster Special Constabulary as an armed, mostly unionist, police force.

The autumn and winter of 1920 saw a new ruthlessness on both sides. On November 21, IRA units in Dublin launched a mass assassination attack on British Intelligence officers, killing 14 men, of whom at least 8 were Intelligence Officers. In revenge, a force of RIC Black and Tans and Auxiliaries shot dead 15 civilians at a football match in Dublin’s Croke Park, in a day known as Bloody Sunday. A week later a patrol of 17 Auxiliaries was wiped out in an IRA ambush at Kilmichael in Cork and shortly after that much of Cork city centre was destroyed in a fire set by Crown forces.

By the end of 1920 some 500 people had been killed. There were attempts to call a truce in December but this was prevented by the British government, in particular, Hamar Greenwood, the Chief Secretary for Ireland who insisted that the IRA surrender its weapons first.

In the first 6 months of 1921, around 1,000 people were killed in the fighting. The violence was most intense in Dublin city, south Munster and Belfast, although there was some guerrilla activity in most areas. County Cork saw almost 500 people killed (in actions like the Upton ambush) and Dublin 300, while at the other end of the spectrum County Cavan saw only 9 deaths and Wicklow 7 (See here). In addition some 6,000 republicans were imprisoned.

Martial or military law was declared in the province of Munster. The regular British Army was deployed in greater numbers, mounting, ‘sweeps’ across the countryside and the British authorities began ‘official reprisals’ including house burnings and executions, in response to IRA attacks. The IRA retaliated by stepping up shootings of informers (real and alleged), eventually extending attacks to off-duty British personnel and burning the property of loyalists. When the British began executing prisoners the IRA also began shooting captured British soldiers and police.

By the summer of 1921, the IRA was very short of ammunition and weapons and many fighters had been imprisoned, notably in the raid on the Customs House in Dublin. British forces claimed they were on the verge of defeating them but the guerrillas had also improved their bomb making capabilities, were still inflicting casualties and no immediate end was in sight to the conflict.

The fighting was brought to an end however, on July 11, 1921, when a truce was negotiated between British and Irish Republican forces so that talks on a political settlement could begin.

In the north, though, the second half of 1921 was more violent than the first with extensive fighting between republicans and loyalists, Catholics and Protestants, especially in Belfast.

Truce and Treaty

The truce allowed the IRA to regroup, recruit and train openly. Many of their activists believed at first that it was just a temporary end to hostilities.

However, in December 1921, an Irish delegation led by Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith, signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which disestablished the Irish Republic of 1919 but created the Irish Free State, an entity comprising 26 of Ireland’s 32 counties which had much more independence than the Home Rule Act of 1912 would have granted.

Much of the IRA was unhappy with the settlement though and this eventually led to civil war among nationalists in 1922-23, before the new Irish Free State government was established. (See Overview of the Irish Civil War).

Violence did not totally end with the truce in the south of Ireland. British troops remained in garrisons until the spring of 1922 and the final 6,000 soldiers did not leave until December 1922. There were a substantial number of killings of serving and former RIC personnel, and some killing of civilians, by the IRA – notably 13 Protestant civilians around Dunmanway in Cork, it is thought because they were suspected informers, in April 1922.

However, the last major spasm of violence was in Northern Ireland, whose existence was confirmed under the Treaty. In early 1922, both pro and anti-Treaty wings of the IRA fought a clandestine campaign against Northern Ireland, tacitly supported by elements of the Provisional Free State Government led by Michael Collins. This culminated in a failed IRA offensive in May 1922, in which the guerrillas fought a number of sizable engagements with British troops at the villages of Pettigo and Beleek in Fermanagh, but overall failed to coordinate their actions and were imprisoned in large numbers by the Northern government.

Loyalists, in a number of cases with the help of the RIC and the Ulster Special Constabulary launched attacks on Catholic areas of Belfast in reprisal. In one instance wiping out the male members of a Catholic family – the McMahons in revenge for the killing of policeman. The IRA in Belfast also carried out killings of Protestants, including bombing the trams taking workers to the shipyards.

However the civil war in the south that broke out in June 1922 and the Northern government’s introduction of wholesale internment led to the complete defeat of the republicans there by mid 1922.

Results

If taken from 1917 up to mid 1922, the conflict produced in the region of 2,500 deaths.

Its political results were the creation of the substantially independent Irish Free State (since 1948, the Republic of Ireland and fully independent) and Northern Ireland, which remained part of the United Kingdom.

The Irish Free State and later Republic was the first fully independent functional Irish state in recorded history.

The memory of the War of Independence was tarnished by the subsequent civil war but it was openly celebrated up to the 1970s as marking the foundation of the Irish state. After the outbreak of the Northern Ireland conflict in 1969, public memory began to be more critical with more focus on the killing of civilians and the lack of democratic endorsement of the IRA campaign.

However since end of the Northern conflict after the late 1990s, more positive views of the 1919-21 period are again in the ascendant in nationalist Ireland – though aspects of it continue to be bitterly debated.

More features on the War of Independence here.