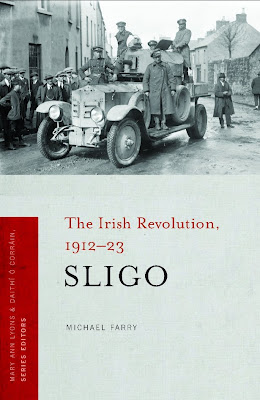

Book Review: Sligo.The Irish Revolution 1912-23

Four Courts Press, 2012

Reviewer: John Dorney

This new book on county Sligo’s experiences in the upheaval of 1912-23 is the first in a series of new works by Four Courts Press that will publish local studies of the Irish revolution. Michael Farry’s slim but useful book takes us through how Sligo experienced political mobilisation and guerrilla war.

Like most rural Irish counties in 1912, Sligo was dominated by the Irish Parliamentary Party, the United Irish League and its press. The labour movement was getting organised in Sligo town and there were a number of bitter strikes on the docks. Similarly there was a small nucleus of IRB and Gaelic League activists but nothing that threatened the Home Rule Party’s hegemony.

However Home Rule itself was only moderately popular and UIL activists had to go to a great deal of trouble to organise rallies in support of the Bill.

Farry supports the thesis that the Irish revolution was triggered not so much by internal contradictions of British rule in Ireland as by the twin crises of the Home Rule crisis, where the rival unionist and nationalist parties formed antagonistic Volunteer militias and the First World War. In particular the suppression of the Easter Rising in 1916, twinned with the threat of conscription seems to have triggered the collapse in support for the IPP and the growth of the separatist party in Sinn Fein.

The Irish Parliamentary Party was destroyed by the combined crises of Home Rule, the Easter Rising and the First World War

The bind that the Rising put the IPP in – having to condemn ‘men who fought for Ireland’ – is demonstrated by one UIL rally in September 1916, ‘There has been a rebellion (applause) and the men who fought in that rebellion fought as nobly as any men ever fought in any cause (Loud and continued applause). They fought a good fight but gentlemen it was a foolish fight (Several voices, “No!”)’.

The War of Independence in Sligo

In 1918, in Sligo as elsewhere, Sinn Fein swept the boards. One factor made explicit here but not mentioned often enough in general accounts of the period, is that 1918 was the first general election in Ireland that even approached universal suffrage – by the Representation of the People Act that enfranchised all men over 21 and all women over 30, the electorate in the constituencies of North and South Sligo almost tripled. Where, in the county and urban district councils, voting was still a monopoly of rate payers, the Home Rulers retained a presence. The same was true in Dublin.

As elsewhere, the triple crises of the Home Rule stand-off the First World War and the Easter Rising finished the IPP in Sligo

In the War of Independence, despite having a number of powerful local personalities such as Liam Pilkington, Sligo had a slow start, much of the IRA’s early activity was social agitation for land redistribution. In late 1920, a number of flying columns were formed and the RIC police force suffered considerable casualties in a number of ambushes.

However, once paramilitary police in the Auxiliary Division and a British Army regiment were deployed to the county, violence fell sharply as the IRA fighters spent most of their time simply trying to avoid capture and blocking roads to impede the movement of Crown forces. In Sligo neither side was very ferocious, the British did not engage in wholesale house burning or assassination –though they did burn some creameries in retaliation for ambushes. And the IRA shot only one civilian as an informer in 1921. Only 19 people died in the county up to the Truce of 1921.

Unlike other parts of the Ireland, 1921 in Sligo saw a dramatic fall off in casualties

This is a pattern quite different from that in the southern counties such as Cork, Kerry and Tipperary that were put under martial law, and where in early 1921 hundreds were killed by both sides. British forces killed many civilians and the IRA began shooting anyone suspected of passing information to Crown forces. In north midland counties such as Monaghan, Longford and Leitrim the numbers were smaller but the pattern of escalation was similar. So Farry’s book is a reminder that British tactics did not always necessarily fail and that experience of the War of Independence was very varied across Ireland.

The Civil War

The Civil War of 1922-23 by contrast saw 48 people killed in County Sligo, almost all of them from July to September 1922 as Free State forces wrested control of the county from anti-Treaty forces. The Civil War also saw almost three times as much material damage as the war against the British. The main reason for this was that the truce period had left the IRA in control of the county, free to recruit and to arm. By contrast with their meagre armament from 1919-21, they now had ample rifles, machine guns and even had armoured cars. Due mainly, Farry argues, to the charismatic leadership of people like Pilkington and Frank Carty, the IRA in Sligo (with the exception of a south Sligo unit loyal to pro-Treaty TD Alex McCabe) almost unanimously opposed the Treaty settlement.

I was somewhat dissatisfied with Farry’s analysis of the civil war however. He argues, following Tom Garvin’s argument, that the IRA in the truce period, full of their own self-importance, operated as ‘public band’, defying elected and legal authority, interfering in local politics and effectively mutinying against the popular will in rejecting the Treaty. It is not that there is no truth in this; in Sligo Farry shows how they physically intimidated pro-Treaty politicians in the spring of 1922. But in Sligo at least, as Farry tells us, there were twice as many anti-Treaty as pro-Treaty votes in the election of 1922. The local IRA therefore clearly represented more than just themselves and a more thorough look at their politics might have been illuminating.

The Civil War was three times as destructive in Sligo as the War of Independence

Also, while Farry does cover the labour movement and the land question ( which contrary to what is often said, was far from solved by 1922), they disappear from the narrative by the civil war and events such as the 1923 election and the 1923 Land Act – both surely central in assessing the long term importance of the nationalist revolution – are not covered at all.

The sectarian or communal question is better covered. Farry shows that while never irrelevant, sectarian division between Catholic and Protestant was never the central axis of revolutionary conflict. In 1913, some Sligo Protestants did travel to join the Ulster Volunteers but in 1914, others offered to officer Redmond’s National Volunteers, who supported the British war effort in 1914-18. Protestants were never systematically targeted by the IRA in Sligo but in early 1922, with hundreds of Catholics being killed in Belfast and central authority evaporating with the British withdrawal from southern Ireland, some Protestants in the county did suffer from robbery and intimidation. As a result , most Protestants in Sligo welcomed the Free State restoration of order by mid 1923 with relief.

Overall this is a useful book and the prospect of more local studies like this being published is an attractive prospect.