Daniel O’Connell’s Childhood.

Brian Igoe looks at ‘The Liberator’s’ early years.

Brian Igoe looks at ‘The Liberator’s’ early years.

It was an August Sunday, the 6th day of that month in 1775, the day Catherine O’Connell was brought to bed of her second child. Morgan and she had chosen the name already, Ellen if it was a girl, and Daniel, after his uncle, if it was a boy. This one was a boy, so it was Daniel, no longer ‘it’. A brother for Mary who was almost three now. The great Daniel O’Connell, The Liberator, had come into the world.

The particular bit of the world to welcome him was Carhen, where his father Morgan had built his house. It wasn’t a big, pretentious house like that of Morgan’s older brother beyond at Derrynane, but it suited him and his retiring ways. A quiet man, Morgan was the second surviving son of Donal Mór, Big Donal, and the family was one of the very few ancient great families of the native Irish left in the country. But then Carhen was in Kerry.

The Kingdom of Kerry

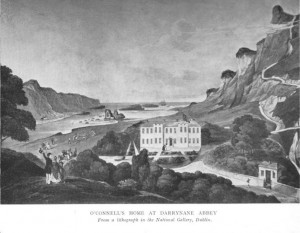

The County of Kerry was not independent of Ireland, but it might as well have been, in 1775. There were no real roads beyond nearby Cahirciveen, save to the ancient castle of Littur down the lane, so that the O’Connell’s great house of Derrynane a few miles to the south east over the hills was accessible only by sea, horseback, or Shanks’ Nag, to use a modern idiom. It remained so until 1839, when a new road there was completed. And from the sea it was difficult of access, because the entrance to the harbour was all but invisible from half a mile away.

There were no real roads beyond nearby Cahirciveen, so the O’Connells’ great house of Derrynane a few miles to the south east over the hills was accessible only by sea or horseback.

The house itself was set a few hundred yards from a small bay, and the bay was separated from the harbour of Ballinskelligs by a rocky promontory, the AbbeyIsland. It was called ‘Island’ because it was sometimes cut off in particularly high tides. On it were the ruins of an ancient abbey, and the whole area was surrounded by romantic hills and cliffs, with mountains up to 2,000 feet high protecting it from the north and west. To the east there was a chain of high rocks that divided the bay of Derrynane from that of Kenmare. The eternal roar of the mountain streams bounding through rocky defiles provided a continuous background to the ear in that beautiful place.

The clan had been rulers in Kerry since time immemorial, with records going back at least to 1337 when Hugh O’Connell was chief of the ’O’Connell nation’. Head of the Clan, when Daniel was born, was his Uncle Maurice, Morgan’s elder brother. Maurice was always called ‘Hunting Cap’. He hated paying taxes, and new and inventive ones were always being introduced. A new tax had been introduced on Beaver Hats, almost universally worn by Irish gentry then. Beaver fur was the raw material for a high quality felt suitable for hat making. Felted beaver fur could be processed into an excellent hat that held its shape well even after successive wettings, making it perfect for Ireland. Maurice was so incensed about this tax that he promptly gave up wearing Beaver Hats and instead wore a ‘chaipín’, or hunting cap (bottom picture). Ever after he was known as ‘Muiris an Chaipín’ or Maurice the hunting cap. Or in English, just plain ‘Hunting Cap’.

Hunting Cap was 13 years older than Morgan, which gave him an authority over his siblings based more on habit that anything else, but absolute nonetheless. That was to have a huge impact on the development of DanielO’Connell.

Fostered to the Cahills and early education

But for now, Daniel had to grow up. So the baby Daniel was fostered out to the Cahills, the family of Morgan’s head Cowman, and he grew to the age of five speaking only Irish. In later years he would remember it as a happy time, and he would remember the Cahills as his ‘Da’ and Nan’. His real parents were Mother and Father.

Daniel of course learned all about the peasant children’s ways. Meat was always scarce, but they all used to catch birds, especially thrushes and blackbirds, for they made the best eating. The Cahills had a son a few years older than Daniel who amongst his other achievements was a very skilful bird catcher, good at making ‘cribs’ and other traps. Many a thrush and blackbird he captured and brought home to liven the evening meal, and many a robin he caught and let go. For the robin (in Irish, the spiddóge) is, as is well known, a blessed bird, and no one, no matter how wild or cruel, would kill or hurt one, partly from love, partly from fear. They believed if they killed a robin a large lump would grow on the palm of their right hand, preventing them from working, and perhaps more importantly from hurling. It is fear alone, however, that saves a swallow from injury, for it is equally well known that every swallow has in him three drops of the devil’s blood.

Daniel was fostered out to the Cahills, the family of Morgan’s head Cowman, and he grew to the age of five speaking only Irish. In later years he would remember it as a happy time, and he would remember the Cahills as his ‘Da’ and Nan’

All other birds are fair game. When a boy visited his crib, and in it, instead of the blackbird or thrush he hoped for, found a robin, his disappointment was naturally great. The robin he dare not kill, but he would bring the bird into the house, get a small bit of paper, put it into the robin’s bill, and hold it there, and say to it: “Now, spiddóge, you must swear an oath on the book in your mouth that you will send a blackbird or a thrush into my crib for me; if you don’t I will kill you the next time I catch you, and I now pull out your tail for a token, and that I may know you from any other robin.” The tail would then be pulled out and the spiddóge let go. The boy well knew that he dare not carry out his threat, and when he caught a tailless robin, as there was nothing to pull out, he merely threatened him again and let him go. In very severe winters a robin with a tail was rarely to be seen.

When he was five, Daniel came home from Teiromoile to Carhen. The house was imposing enough to a small boy, situated on top of a hill above the bay overlooking Cahirciveen. So much was new to the child, starting with his family. His parents still seemed remote, but he immediately took to his sister Mary, who was eight, and quite beautiful, like a little porcelain doll. And Maurice, a year younger than himself, and incredibly shy. Then there were two babies, Ellen and John.

The rest of the year passed swiftly, and much more happily than was often the lot of youngsters in grand houses in those days. But then the O’Connells were a highly unusual family. The household was almost totally bilingual, and Daniel seemed to have a knack for absorbing new things. So English he found easy. It came naturally really, because everyone spoke it all the time except with the servants. He had ridden a pony almost before he could walk at Teiromoile, something Morgan had surreptitiously arranged. So that wasn’t new. But the clothes were new.

His first teacher was a ‘hedge school’ master named Daniel Mahoney

With English, he learned to read and write, in English first. A schoolmaster named David Mahony had been engaged, one of the itinerant ‘hedge-school’ masters who roamed Ireland still. This one seems to have been a man with a love of literature and, unusually for his profession, a natural ability to make his pupils love it too. When he met Daniel first, he immediately realised that he was very nervous, so he put him on his knee and proceeded to very gently disentangle the strands of his unruly curly head of hair. Daniel’s previous acquaintance with combs had been irregular and painful, and he was immediately captivated, and couldn’t do enough to please Mr.Mahony. He learned the alphabet in an hour, so he used to say! He seems to have been remarkably quick and persevering. As he put it in later years, his “childish propensity to idleness was overcome by the fear of disgrace”. He desired to excel, and couldn’t brook the idea of being inferior to others. By the time he was nine years old he had progressed to books like Captain Cook’s ‘Voyages round the World’. He used to run away and take his book to the window, where he would sit with his legs crossed, tailor-like, devouring the adventures of Cook.

The O’Connells and their ‘Trade’

In the big wide world outside, this was the time of Grattan and the repeal of Poyning’s Laws, the first palpable fruits of the mood of reform sweeping through Ireland. It was the beginning of what became known as Grattan’s Constitution. Heady stuff it was too, but hardly for a nine year old boy. Much more exciting were the adventures at home. For the O’Connells were in ‘trade’. They had great salt pans and tanneries on the coast, and Daniel loved watching the pans bubbling away down on the strand. By some magic they bubbled until there was no water left, and there in the bottom of the pan was salt! Even better he enjoyed helping with the loading of the salt and the cured hides onto small ships that came into Derrynane harbour at night, and left before the dawn. It was all very mysterious and exciting, and great fun. In truth, the O’Connell ‘trade’ would have been called ‘smuggling’ in many other places, but in Kerry, the ‘Trade’ involved almost everybody within a mile of the sea, including the O’Connells.

Especially the O’Connells, in fact, and Hunting Cap was the smuggling chief of the county, indeed of the whole west coast, and he grew very rich on the trade. Much richer than Morgan. Many of the members of the local ‘Grand Jury’, the body of local landowners who still had a dual government and judicial role, were on his books. All, of course, turned a blind eye to the trading activities which supplied them with tea and brandy. Hunting Cap’s outward consignments would usually comprise large sacks of wool, firkins of butter, salt and salted hides. Butter was a major influence on the lives of Kerry people, and they produced tons of it. Mostly it was sold in the great Butter Market in Cork, and long roads were built to get it there. ‘Butter Roads’ they were called, and still are.

Maurice ‘Hunting Cap’ O’Connell, the patriarch of the family became wealthy through smuggling butter, salt and hides out of the Kerry coast and tea and brandy in

Amid all this excitement Daniel was growing up. It may have been because of Hunting Cap’s money, or because of his position as patriarch of the O’Connells, or maybe just because he had no children of his own and took a liking to young Daniel. Whatever the case, he virtually adopted him, arranging all his schooling and becoming a second father to him. So Daniel spent much of his time at Derrynane, which was nicer than Carhen anyhow. It was a wonderful place for an active boy. The house was set in a garden known as ‘the shrubbery’, in the middle of which was an ancient turret with views over the sea, the trees and the hills.

This was a favourite hideaway for young Daniel, and indeed remained so long after the house had become his own, forty years later. The house was then a rambling, higgledy-piggledy sort of place, where rooms had been added on as needed by succeeding generations. Daniel was particularly fascinated by a memento of the old evil days, a piece of the skull of a friar who had been cut down by one of Cromwell’s soldiers with a sword, while saying mass. In later years he had it interred in the grounds of the old Abbey.

An education in revolution – O’Connell in France

By the time he was 14, it was clear that Daniel needed a more formal education. Fortuitously this was a time when the Penal Laws were being relaxed enough to allow the establishment of Catholic Schools. And now in 1789 Daniel was 14, and he was ready for a proper School. That would normally have been in France. But 1789, of course, was the year the French Revolution broke out and the Bastille, the Royal stronghold in Paris, was stormed and taken by the insurgents. Members of the O’Connell family had always been leading figures in the Irish Diaspora in Europe.

The current O’Connell representative in this great Diaspora was Hunting Cap’s youngest brother, Daniel Charles, now Count O’Connell, 45 years old, and a colonel of the Irish Brigade in France. Count was a military title, denoting command of a regiment, and entitling it’s owner to the highest court honours, to the extent even of riding in the Royal Carriage. But that had been six years ago when he was not quite 40, and the royal throne to which the Count was obligated was now showing every sign of toppling. The Count strongly advised against any travel to France for the time being.

Daniel and his brother were sent to France to study law in 1792, at the height of the French revolution

One of the new Catholic Schools now being opened was at Long Island in Cork, run by a Father James Harrington. Thither Daniel and his brother Maurice were sent. Daniel was zealous to a fault, not because of the pain of a beating which would inevitably follow lack of zeal, but as he said later, because of the indignity and disgrace of not coming top. However the next year the Count, pressured by Hunting Cap in far off Kerry, conceded that it might be safe to go at least to the Low Countries, and it was decided that he and his brother should after all go to the school confusingly called ‘the College of St. Omer’ which had been in Liège in the Low Countries for the last seventeen years. It was a well known Jesuit school, and had originally been in St. Omer in France, hence the name. It would move from Liège to England three years later, and become Stonyhurst College, still today a famous Jesuit school.

The Count, however, was in error. By now they were too old for the College of St. Omer in Liège. So they eventually ended up at the English College in St. Omer run by Dr. Gregory Stapleton. It was no longer a Jesuit establishment, for the Jesuits had been suppressed in France as part of a worldwide Papal motion 28 years earlier. It was then that the Jesuits and most of their students had moved to the Low Countries.

The French St. Omer school was now run under the auspices of the Crown by lay staff. So it was to a secular school that Daniel and Maurice presented themselves in January 1791. But their days there were numbered, for the Crown lay uneasily on the King’s head. For the present the Crown was doing a very good job indeed in St. Omer. The boys were taught Latin and Greek (and studied the Latin and Greek authors), French, English, and Geography. They had to speak French normally, which left Daniel with a slight French accent when speaking some English words for the rest of his life. They also had lessons during ‘free time’ in music, dancing, fencing, and drawing. The food was good, and the school owned a country house situated in a beautiful valley about a mile from the town, to which all the boys went for a day once a fortnight. This made the summer ‘very agreeable’, wrote Daniel.

When the new school year began after Easter, they found themselves on a new footing, for they had been promoted. They now read Mignot’s harangues, Cicero, and Caesar. These were their Latin authors, though they were read over without any study beforehand. Caesar was given chiefly to turn into Greek. Their Greek authors were Demosthenes, Homer, and Xenophon’s Anabasis. Their French one was Dugard’s Speeches. But Philosophy was not taught at all. There is no doubt that Daniel profited much from this enlightened school. His memory developed prodigiously, something which was to stand him in very good stead in life. And he must have been good at his studies for he continually came top of his class. It seems to have been around this time, too, that he developed a religious bent, though not to the extent of wanting to join the Church. He knew even then that his interest in girls would preclude that vocation!

He was also developing a strong interest in the law. The world around him was increasingly lawless, and his interest in laws and what they made lawful was excited. He was a very serious 16 year old. Dr.Stapleton was in fact a Priest, and ten years later was to be a Bishop and Vicar Apostolic of the Midland District in England.

It was he who left on record, in reply to an inquiry by Hunting Cap concerning the progress of his nephews, the prophecy that he “never was so much mistaken in my life unless he be destined to make a remarkable figure in society.” The subjects taught at St Omer, however, had no relevance to anything remotely legal – and in particular, no rhetoric or philosophy, both essentials to a study of law in 1792. Just languages, geography, mathematics and so on.

So Daniel had been making enquiries for somewhere where they could study philosophy and rhetoric for the last year, and had found Douai, about fifty miles to the south east. The EnglishCollege at Douai was a school established by the Benedictines, primarily for the education of English boys destined for the priesthood. But they taught philosophy and rhetoric. Daniel accordingly wrote to both uncles, and in due course they moved to this famous EnglishCollege at Douai, arriving in the middle of the summer of August 1792, a few days after his seventeenth birthday.

The O’Connells were nearly lynched by republicans calling them, “Young Priests!” and “Little Aristocrats!”

With hindsight, their timing could hardly have been worse, but at the time the countryside of France seemed to be at peace, the Revolution and the war with Austria notwithstanding. The storming of the Bastille three years earlier was now just a memory. The Battle of Valmy against invading Austrian and Prussian forces the previous month seemed a world away at more than 200 kilometres to the south east. A new Constitution had theoretically established a Constitutional Monarchy.

The King retained a ‘suspensive veto’ (he could delay the implementation of a law, but not block it absolutely). And at the College at Douai the new ‘Civic Oath’ imposed on the clergy the previous year did not apply, for when the members of the British establishments claimed exemption by virtue of their nationality, it had been granted. Everything seemed so normal. They were more concerned with their lack of funds, the poor and inadequate food, and the totally different regimen from St. Omer, than the political situation.

But that was to change. Dramatically, as the Colonel had been warning them. The straw which broke the camel’s back, so to speak, was an incident which took place while General Dumouriez was marching to Hainault just 80 miles to the north east, where he was to beat the Austrians at the Battle of Jemappes on November 6th, 1792, the big guns almost within earshot of the school. His wagons were passing through Douai, and one of the waggoners saw the two boys and some other students out walking, and shouted “Voilà les jeunes Jesuites, les Capucines, les Recollects!”. There was no doubting the hostile intent of the waggoner.

They fled back to the college, but were badly frightened. And they no longer had their Uncle the Count Colonel to call on. Daniel wrote to Hunting Cap of the present truly alarming state of affairs in France, and emphasised that it would be no exaggeration to say that they feared for their lives. Hunting Cap acted immediately, although it still took six weeks for the letter to reach him and his reply to reach the boys. Instructions did arrive however, and they left Douai for England on January 21st,1793, and only just in time.

The French King was in fact beheaded on the same day, and feeling against anyone not patently a French Commoner ran high everywhere. In St.Omer Dr.Stapleton would soon be arrested, and spend the next two years in gaol. Daniel’s protestations that they were Irish made not the slightest difference, and their carriage was attacked on the way to the port by Republicans screaming at them “Young Priests!” and “Little Aristocrats!”.

Perhaps due to their tricolour cockades which they had put on in the hope that they might offer some protection, they made it unscathed to the packet boat for England. As they were preparing for sea, two new arrivals boarded, loudly declaiming how they had actually been present at the execution of the King. They boasted that they had bribed two of the National Guard to lend them their uniforms, and they showed them a handkerchief stained with the blood of the ill-fated monarch. Daniel asked how, in Heaven’s name, they could bear to witness such a barbaric, hideous spectacle. The answer horrified him. “For the love of the cause”, they said. Cork men both, these were the brothers John and HenrySheares. As soon as they were under way, Daniel and Maurice threw their cockades into the sea.

Daniel and Maurice duly arrived in London, and their timing on this occasion had been excellent. The year 1793 saw Grattan’s third Catholic Relief Act, which removed most of the barriers that had existed preventing Catholic advancement. They could now be Grand Jurors, enter universities and a be appointed to an enormous range of positions from which they had hitherto been barred. They could even serve as Army Officers, although admittedly positions senior to Colonel were still barred to them. And above all, they could now be barristers, though not yet could they aspire to that most high office in the most honourable institution the Irish Bar, that of King’s Counsel.

The remaining strictures did not, of course, impinge on the ordinary person in the street, and Hunting Cap, the onetime smuggler baron, was immediately appointed Deputy-Governor for CountyKerry, a position which transformed his life. What could better illustrate the change this one piece of legislation made? And as a practical illustration of the change, he now determined that the boys should become barristers, and started to make appropriate arrangements.

Hunting Cap’s brother the Count Colonel, however, was in difficulties. The Irish Brigade had been disbanded the previous year, and Colonel O’Connell, now unemployed and no longer rich, had arrived in London some months before. His old friend and former Commanding Officer, the Chevalier Fagan, had lent him some money to start, and Hunting Cap now helped too, so that by the time the two boys arrived he was able to look after them. And Chevalier Fagan had a relation who ran a boy’s school, so to Fagan’s they were sent while arrangements for law school were made.

They stayed at Fagan’s for most of 1793, while Hunting Cap was settling into his new rôle which had, in truth, changed prospects for ambitious Catholics in Ireland out of all recognition. The end of the last term of ’93 at Fagan’s was the end of Daniel’s schooldays. He was now a big, strapping eighteen year old, always good humoured, and always popular. After the Christmas and New Year holidays he was admitted as a student in Lincoln’s Inn, London. But that is another story.

Brian Igoe is a historian and author. He has written a number of books on Irish history, including The Story of Ireland, which you can view here.

Sources:

Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/Daniel O’Connell

Cronin, Mike, ‘A History of Ireland’, 2001

Houston, Arthur, ‘Daniel O’Connell: his early life, and journal, 1795 to 1802’. ll.b., Dublin, 1906

Fitzpatrick, W. J., ‘Correspondence of Daniel O’Connell, the Liberator’, John Murray, London, 1888

Hull, Eleanor, ‘A History of Ireland and Her People’, 1931

Hamilton, J. A. ‘Life of Daniel O’Connell’, London,1888.

O’Connell, Basil Morgan (ed.), O’Connell Family Tracts

O’Connell, Maurice R., ‘Correspondence of Daniel O’Connell’, IRISH UNIVERSITY PRESS Dublin

And Miscellaneous on-line newspapers and articles.