Body and Soul of the nation – Early 20th century Irish nationalism and Zionism

In an earlier article Aidan Beatty looked at the shared history of Irish nationalism and Zionism, and how activists in both movements saw echoes of their own histories in each other. Here he examines parallel ideologies.

The Irish and the Jews, since the late nineteenth century, have faced a very similar set of problems. The ‘Jewish Question’ of nineteenth century Europe shared a strong similarity to British society’s contemporary ‘Irish Question’; ‘a hegemonic or dominant majority group that discriminated against a subaltern or minority group called the latter a “problem,” suggesting that the members of the group were themselves mainly responsible for its disabilities.’[1]

There are striking similarities between anti-Irish, anti-Black, and anti-Jewish stereotypes in nineteenth century America, which drew heavily on contemporary European ideas of racial inferiority.[2] In many respects Zionism and Irish Nationalism, rather than just being straightforward movements for national liberation, were also concerted efforts to disprove this inferiority, to ameliorate these supposed national disabilities.

‘Deformed Bodies’ – anti-Semitism and anti-Irish racism in the 19th century

But what exactly were these disabilities? In The Jew’s Body, his seminal study of anti-Semitism, Sander Gilman persuasively argued that bodies, specifically the allegedly deformed bodies of Jews, are often the places where anti-Semitism occurs.[3] For anti-Semites, the archetypal Jew’s body expresses all that which they believe objectionable about Jews; and there is a not dissimilar situation in anti-Irish racism in the nineteenth century.

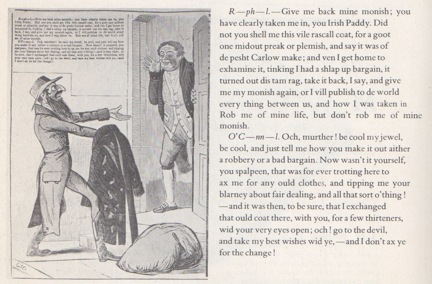

Bodily deformities, for instance, play a central role in how both Irishness and Jewishness are represented in this 1835 cartoon crudely satirising the political relationship between Daniel O’Connell and Alexander Raphael, who was elected that year on a Liberal ticket in a by-election in Carlow, but was prevented from taking his seat due to his not being a Protestant or Catholic. Oddly, Raphael, who was not Jewish but an Armenian Orthodox Christian was nonetheless imagined as being Jewish. Perhaps it was because Armenians, like Jews, have similar origins on the borders of East and West and are a Diasporic people often stereotyped as having natural predilections for merchant capitalism, or perhaps it was because O’Connell had already become well known as an advocate for Jewish political emancipation.

In this area of how “Jewish” and “Irish” men are “imagined” that we can see something very interesting; both are imagined as deformed and deficient men, and their bodily deformities clearly signify their deeper ethnic deformities. Raphael’s disheveled black clothing and hooked nose mark him out as a dysfunctional Jew. His weak legs and arms signify his lack of enervating physical labour while his slightly stooped back is a result of how much he studies religious texts instead of engaging in “real” work.

O’Connell’s rosy cheeks are signs of a different dysfunction, alcoholism, while his pot-belly advertises his own physical laziness. Both men also speak a deformed English that alerts us to their true, inescapable, Yiddish- or Irish-speaking origins. Additionally, O’Connell is depicted as a seller of used clothes, a stereotypically Jewish profession, but calls Raphael a ‘spalpeen’, a wandering day-labourer, a stereotypically Irish occupation; these two men are interchangeable in their deformities.

Both Irish and Jews were imagined by others as deformed and deficient men, and their bodily deformities clearly signify their deeper ethnic deformities.

Also, both figures are implicitly being compared to a third figure, a normal, physically-fit and productive member of the English nation. ‘The contrast of craven Paddy and manly John Bull was one of many dichotomies used to frame and reinforce an idealized conception of Britain and the British.’[4]

Indeed, the idea that Irish men or Jewish men were somehow inferior to English, German or other mainstream European men was a perennial theme in nineteenth century anti-Semitism and anti-Irish racism, a message often absorbed by Irish and Jewish people themselves.[5] Irish scholar Declan Kiberd argues that it is within the tortuous relationship between Britain and Ireland that the very notions of Britishness and Irishness were invented.

Starting with the last Gaelic writers, who chronicled the disappearance of their society in the face of English, and English-language encroachment, Kiberd highlights the construction, in opposition to Anglophone culture, of Irish identity, as well as the subtler manner in which polite English manners and mores were buttressed by perceptions of the supposed lack of the same among the recalcitrant Irish. In all this, Kiberd sees echoes of Frantz Fanon’s three stages of colonialism: colonial oppression, followed by a nationalism aping the forms of the metropole, and ultimately a liberated, and liberating, culture which dictates its own forms.[6]

As well as Fanon, there is certainly something about Irish nationalism and Zionism that bears comparison to Albert Memmi’s vision of the colonizer and the colonized as two inextricably entangled groups, with the colonized ever on the receiving end of a bewildering complex of the colonizer’s negative stereotypes and accusations. Backed up by military and political power, these stereotypes have a strong effect on the politics and identity of the colonized; he implicitly accepts that he is riddled with supposed deficiencies, even as his nationalist, anti-colonial politics descends into xenophobic hatred of the colonizer.[7] Irish identity is, in many ways, a product of this dialectical relationship between a powerful British culture and a weaker Irish culture much like how Ashkenazi (East European) Jewish identity is often a product of a similar relationship between a powerful European mainstream and a politically weaker culture.

It would perhaps be a mistake, though, to ascribe all of Irish or Jewish identity solely to these kinds of power relationships. This is not least because unlike more ‘pure’ examples of colonialism, where the colonial subjects were disparaged as utterly alien to European values, the Irish and the Jews were generally seen, in the nineteenth century, as being part of Europe, though perhaps more of the periphery than the mainstream. There is a shared ambiguity to Irish and Jewish identity politics in the nineteenth century; they both inhabit the status of being, as Homi Bhabha has defined it, ‘not white and not quite.’[8] The obsession with social engineering, with curing supposed national deformities, that characterized both Irish nationalism and Zionism can be seen, at one and the same time, as a response to European racism, as well as being part of a general European anxiety about the supposedly corrosive effects of industrial capitalism, of feminism, of modernity itself.

Nationalism and Social Engineering

This ambiguity, of being both European and yet somehow not European, is probably the most basic similarity shared by these two European minority national movements. It also explains why both movements put such a large emphasis on proving they were European, and on ameliorating those supposed national defects that were seen as detracting from this European status. Indeed, both movements proffered some remarkably similar solutions to their supposed national deficiencies.

Both Irish and Jewish nationalists in the early 20th century thought that only political self-determination could overcome ‘moral and spiritual slavery’.

The most basic one was to acquire political sovereignty. In one of the earliest Zionist texts, Auto-Emancipation (1882) Leo Pinsker, a Russian-Jewish physician, drew some broad links between a lack of sovereignty and the continuous resurgence of anti-Semitism; there had been a wave of anti-Jewish violence in Russia that year, in the aftermath of Tsar Alexander II’s assassination. Central to Pinsker’s analysis is the idea that ‘Among the living nations of the earth the Jews are as a nation long since dead.’ This, he believed, was the cause of anti-Semitism’s perennial recurrence across European history:

With the loss of their country, the Jewish people lost their independence, and fell into a decay which is not compatible with existence as a whole vital organism. The state was crushed before the eyes of the nations. But after the Jewish people had ceased to exist as an actual state, as a political entity, they could nevertheless not submit to total annihilation — they lived on spiritually as a nation. The world saw in this people the uncanny form of one of the dead walking among the living. The Ghostlike apparition of a living corpse, of a people without unity or organization, without land or other bonds of unity, no longer alive, and yet walking among the living — this spectral form without precedence in history, unlike anything that preceded or followed it, could but strangely affect the imagination of the nations. And if the fear of ghosts is something inborn, and has a certain justification in the psychic life of mankind, why be surprised at the effect produced by this dead but still living nation.

And much as Pinsker had a simple explanation for the roots of ‘Judeophobia’, so he also had a simple solution: the Jews must have a state of their own. ‘The proper, the only solution, is in the creation of a Jewish nationality, of a people living upon its own soil, the auto-emancipation of the Jews; their return to the ranks of the nations by the acquisition of a Jewish homeland.’[9] This text, short but influential, would have a major impact on Hovvei Tzion [The Lovers of Zion], the first Zionist organisation, who established Rishon LeTzion (First to Zion) the first Zionist settlement in Palestine.

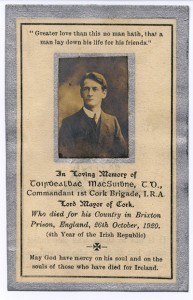

Pinker’s ideas bear more than a passing resemblance to the arguments advanced in Terence MacSwiney’s Principles of Freedom, originally written in 1912. MacSwiney also believed that a lack of political sovereignty had led to corruption and ‘national subjection’[10] and even the language used is strikingly similar to that of Pinsker:

The moral plague that eats up a people whose independence is lost is more calamitous than any physical rending of limb from body. The body is a passing phase; the spirit is immortal; and the degradation of that immortal part of man is the great tragedy of life. Consider all the mean things that wither up a people in a state of slavery… the soul of that people become spectacles of disgust, revolting and terrible, terrible for the high things degraded and the great destinies imperilled.[11]

Moreover, just as a lack of national sovereignty had caused this degradation, so a return to sovereignty would, of course, make the Irish whole again, a nation with a state like any other normal European nation. Indeed, would Auto-Emancipation not be an apt translation for Sinn Féin?

‘Not only slaves but very eunuchs’ – Nationalism and Masculinity

By no means was MacSwiney alone in internalising the idea that the Irish were a degraded and inferior people in need of a national cure. In his famous 1913 essay, The Murder Machine, Patrick Pearse talked of how the British educational system had made Irishmen ‘not slaves merely, but very eunuchs.’[12] A year later, in a speech delivered in Philadelphia, during his tour of the US, Pearse again talked of how an ‘anglicizing’ education was ‘emasculating our boys and corrupting our girls.’ He saw this as clear evidence of an English government conspiracy to enslave Ireland and cut off future generations from a proud history. Thus Irish schoolboys ‘were not taught to be brave, to be strong, to be truthful, to be self-reliant and to be proud.’[13]

But where MacSwiney talked of sovereignty as the cure, Pearse here suggested that a revival of the Irish language, and thus a return to an ancient Irish culture, would restore pride and national honour.

This, indeed, was a recurring trope in the Gaelic Revival. An early editorial in An Claidheamh Soluis, for instance, talked of how the language was a link to a mythical past, and that without this link the Irish people would be a deficient people, lacking an important element of their heritage:

The customs, beliefs and dreams of their forefathers were embalmed in it; it preserved undying the image of Ireland clothed in the ancient Druid romances. Hence, the extinction of such a language would be to them an irretrievable loss – a gap in the continuity of their national being; the cutting off of their intellectual life; the cutting off of their religious life, their sacred traditions and romances, and their martyrs’ struggles.[14]

All this talk of ‘cutting off’ is strongly echoed in Pearse’s view that Anglophone education was like ‘an edict for the general castration of Irish males.’[15]

‘this other tongue [English]… is a living and constant reproach to us, a constant reminder that we are an enslaved nation’, Brian Ó hUiginn, Sinn Fein Ard Fheis 1932. Zionists felt the same about ‘diaspora languages’, like Yiddish.

Parallel to such views, as Brian Ó Conchubhair has argued, was the common perception that ‘An té a labhair Béarla amhain, ba faoi smacht Shasana a bhí a mheabhair’ [He who spoke only English, was under an English mental control].[16] Or, as Brian Ó hUiginn succinctly summarized it at the 1932 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis: ‘this other tongue [English]… is a living and constant reproach to us, a constant reminder that we are an enslaved nation, that we are bound body and mind to our one and only enemy in the whole world, and that to be free we must come back to the truth, build up from the foundations again and make ourselves fit for freedom when it comes.’[17] The meaning was clear; by reviving the Irish language, the Irish nation would throw off the shackles of foreign rule and culture and would also be revived and made stronger.

Such sentiments would have been quite recognisable to those involved in the revival of Hebrew. The idea that Hebrew was a manly language, while Yiddish was not just effeminate but effeminizing, has had a long half-life in Jewish history.[18] And just as the revival of Irish was clearly about more than just language, so also the revival of Hebrew would be a key part of “normalising” Jews. Arieh Saposnik, for example, has discussed how those involved in the modern Hebrew-language culture that emerged in late-Ottoman Palestine had highly negative views of ‘an unhealthy Diaspora and its decaying culture.’ These early Hebrew-speaking Zionists settlers saw their work as part of breaking from a weak and effeminate Yiddish-speaking Diaspora.[19]

Similar ideas feature in Yonathon Ratosh’s 1943 essay, Kitav Al HaNoar HaIvri (Epistle to the Hebrew Youth), a foundational document of the so-called Canaanite Movement.[20] The ‘Caananites’ sought to create a modernized Israelite identity, rooted in the Biblical Homeland, to replace completely the Jewish Diaspora, thus taking the Zionist notion of Shlilat HaGolah (Negation of the Diaspora) to a logical if eccentric conclusion.

Ratosh talked of how Amok HaTahom v’HaZarot [a chasm of different opinions and alienation] separated the proud Hebrew-speaking pioneers from a degenerated Diaspora. Those who spoke Hebrew, Ratosh believed, had freed themselves from the ‘Tavsichim Nephshot’ [mental neuroses] of the Jewish Diaspora, a Diaspora that, implicitly, was Yiddish-speaking. This sense of Hebrew-speaking pride, Ratosh believed, stemmed from their new life, rooted in ‘HaMoledet HaIvrit’ [The Hebrew Homeland].

The Land and the Nation

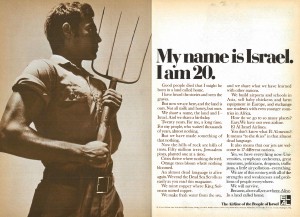

Indeed, land, agriculture and productive physical work were shared concerns of both Zionism and Irish nationalism. Oz Almog, for instance, has identified the importance of the Sabra or ‘new Jew’ in Zionist ideology. (Sabra or, in Hebrew, Tzabar, is species of cactus and just like this cactus the ‘new Jew’ would flourish in the Land of Israel; they would have a tough exterior, but would be tender on the inside. Ironically this species of cactus is not native to Palestine, but was introduced from Latin America in the eighteenth century).

The Sabra was to be the paragon of the new Israeli society and, perhaps most importantly, he was to be a specifically agrarian figure, hard-working, rooted in the soil, with a love of nature and never afraid to defend his patrimony.[21] Even if few Israelis ever lived up to that ideal, the Sabra was still a popular image of how both Israelis and non-Israelis were supposed to view this new society.

Irish nationalism has often held to a similarly romantic view of agrarian lifestyles. In a recent innovative study of The Land War, Anne Kane discussed how many of these standard agrarian tropes of Irish Nationalism (opposition to rent, ownership of the land, the strong farmer) were themselves invented during the agrarian agitation of the late 1870s and early 1880s.[22] These tropes were also highly gendered stereotypes, linked to notions of men rooted in the soil and providing for their wives and children. ‘The strong Irish farmer’ would put an end to the ‘humiliation’ of tenant farmers, who had to be ‘rehabilitated, both symbolically and practically’[23] during the Land War.

Both nationalisms imagined a return to the land as a means of creating a manly new nation.

In other words, like the Sabra, through a process of social engineering an emerging elite created a new image of Irishness. Certainly the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society (IAOS), from its establishment in 1894 sought to reform Irish rural people. A 1900 IAOS pamphlet spoke with trepidation of how the rural Irish were in need of ‘social reform.’ Such reform, the IAOS argued, would improve sanitary conditions, improve agricultural standards and create a more educated and productive rural society, rooted in the soil.[24]

We can see also this process of agrarian social engineering in Simple Advice, an early Gaelic League pamphlet.[25] This pamphlet warned that ‘Irish Ireland does not want the man who props walls with his shoulder; nor him who has neither the strength of will to say “no” to bad companions, nor to drag himself past a tempting public house.’ Instead, readers were urged to adhere to ‘principles of truth, honour, honesty, uprightness and self-control,’ to avoid ‘lying, pilfering and laziness,’ ‘to build up sound character,’ and, ‘to love work.’ In fact, oddly for a pamphlet produced by the Gaelic League, the one thing never urged is to learn Irish!

In any case, that the Gaelic League felt the need to make such stringent demands of its rural members points to their anxieties about a supposedly degraded rural life in need of thorough reform. This kind of rhetoric also popped up during the Anglo-Irish Trade War of the 1930s. Indeed, what was the Economic War if not an attempt to end Ireland’s economic humiliation and create a productive agrarian nation of meaningful labour and hardworking men, part of a broader Irish nationalist project of social engineering?

At the outset of the Economic War, Fianna Fáil published what must rank as one of the oddest pieces of electoral literature ever produced by an Irish mainstream political party.

Despite having the ponderous title The Economic History of the Land of Erin, the four-page pamphlet was written in the style of a child’s fairy tale, and began ‘Once upon a time there lived in Ireland a man who grew wheat….’[26].

This man, like all other Irish men, had been destroyed economically by international capitalism, until a top-hat-wearing ‘prophet,’ a thinly veiled W.T. Cosgrave, promised to save him. Unfortunately, this disingenuous prophet was in league with ‘the Temple of Molesworth’ and ‘the Knights of the Compass and Square and Ring,’ an allusion to Free-Masonry, and so the men, despite their strong desire for meaningful labour, sunk deeper into unemployment, misery and despair.

But the most interesting part of this pamphlet was perhaps its closing lines: ‘IRISHMEN! Let us end that story! Henceforth we will utilise the resources God gave us to provide a livelihood for our own people in our own land. Vote Fianna Fáil.’ In other words, vote Fianna Fáil if you want to win the Economic War, if you want to help create a productive nation of men rooted in the soil via meaningful physical labour, and if you want to help end Ireland’s economic humiliation. Such ideas are obviously very similar to the creation of the ‘new Jew’ and romantic agrarian ideology discussed by Oz Almog. And just as the Sabra was the negation of the image of weak, parasitical and cowardly Diaspora Jew, so the new Irish agrarian man would be the negation of the drunken, stupid and lazy stage Irishman.

Just as the Sabra was the negation of the image of weak, parasitical and cowardly Diaspora Jew, so the new Irish agrarian man would be the negation of the drunken, stupid and lazy stage Irishman

Conclusions

This essay has sought to show that Irish nationalism and Zionism exhibited, in their formative years, a shared set of problems, problems that stemmed from their relationship to a broader European culture that often denigrated and stereotyped them. As both nations underwent a process of modernization in the late nineteenth century, their respective national movements became a means for negotiating modernity, as an emerging elite sought to engineer “normal” nations that could properly interact with the modern world. It is in this shared concern about proving that they were capable of self-rule, about proving that they weren’t a dysfunctional people but were, in fact, a normal European nation, that we can see Irish nationalism’s strongest similarities with Zionism.

[1] Derek Penslar. Shylock’s Children: Economics and Jewish Identity in Modern Europe (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 2001) 9.

[2] George Bornstein. The Colors of Zion: Blacks, Jews, and Irish from 1845 to 1945 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2011).

[3] Sander Gilman. The Jew’s Body (New York: Routledge, 1991)

[4] Michael de Nie. The Eternal Paddy: Irish Identity and the British Press (Madison WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004) 271.

[5] De Nie. ‘The Eternal Paddy’ (2004); Steven Aschheim. Brothers and Strangers: The East European Jew in German and German-Jewish Consciousness (Madison WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983). Michael Gluzman. HaGuf HaTzioni: Leumiot, Migdar v’Miniyot B’Sifrut HaEvret HaChadashah [The Zionist Body: Nationalism, Gender and Sexuality in Modern Hebrew Literature] (Tel Aviv: HaKibbutz HaMeuchad, 2007).

[6] Kiberd. ‘Inventing Ireland’ (1996) 551-561.

[7] Albert Memmi. The Colonizer and the Colonized (Boston: Beacon Press, 1967) 121, 130, 153.

[8] Homi Bhabha. The Location of Culture (New York: Routledge, 2004) 89. Quoted in Boyarin, ‘Unheroic Conduct’ (1997) 262.

[9] http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Zionism/pinsker.html

[10] Terence MacSwiney. Principles of Freedom (Dublin: Brian O’Higgins, 1936) 19

[11] Ibid, 40.

[12] P.H. Pearse. Political Writings and Speeches (Dublin: Talbot Press, 1966) 8-9.

[13] NLI Pearse Papers MS33702 Stenographic Copy of Speech Delivered by Padraic Henry Pearse, Philadelphia, 1914.

[14] ‘The Value of the Irish Langauge and Literature,’ An Claidheamh Soluis, Vol. 1, No. 38, 2 December 1899. Quoted in Brian Ó Conchubhair. Fin de Siècle na Gaeilge: Darwin, An Athbheochan agus Smaointearacht na hEorpa (Cló Iar-Chonnachta: Indreabhán, 2009) 22.

[15] Pearse ‘Political Writings’ (1966) 7.

[16] Ó Conchubhair ‘Fin de Siècle’ (2009) 15.

[17] NLI John L. Burke Papers MS 36124 Item 8. Brian O’Higgins. Gair-Chatha Gaehdeal [Battle Cry of the Gael]: Sinn Féin and Freedom (Dublin: Sinn Féin Bureau, 1932).

[18] Naomi Seidman. A Marriage Made in Heaven: The Sexual Politics of Hebrew and Yiddish (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 1997).

[19] Arieh Saposnik. Becoming Hebrew: The Creation of a Jewish National Culture in Ottoman Palestine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008) 189-190.

[20] The original Hebrew text can be viewed here: http://shnizi.wordpress.com/noarivri/

[21] Oz Almog. The Sabra: The Creation of the New Jew (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 2000).

[22] Anne Kane. Constructing Irish National Identity: Discourse and Ritual During The Land War (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011) 223-233.

[23] Ibid, 29, 112.

[24] TCD Early Printed Books OLS L.6.611 No.22, Co-Operation and Social Life in Ireland, Leaflet No. 22 (1900).

[25] NUIG Stephen Barrett Papers G3/1189 Simple Advice to be followed by all who desire the good of Ireland, and especially by Gaelic Leaguers (n.d.).

[26] UCDA De Valera Papers P150/2096 The Economic History of the Land of Erin (n.d.).