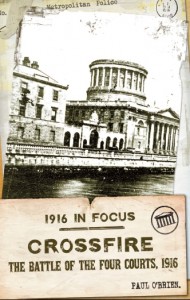

Book Review – Crossfire, The Battle of the Four Courts 1916

New Island 2012.

Reviewer: John Dorney

This book, the latest in Paul O’Brien’s series about the battles of Easter week 1916, about the fighting around the Four Courts and North King Street, contains little about the idea of ‘blood sacrifice’, romantic nationalism, democratic mandate or the usual tropes that dominate writing about the rebellion.

This is probably a good thing. Too much ink has been wasted on these , often circular debates and not enough spilt investigating what actually happened on the ground in Dublin in 1916 – to the extent that many people are aware of the myth but have little grasp of the week’s actual events. Far from the relatively well-known events at the Volunteer Headquarters of the GPO – often presented as a kind of theatre or high farce, O’Brien shows that less than a kilometre away, the most bloody and harrowing close quarter fighting was taking place in the narrow slum streets behind the Four Courts.

Rather than being taken through the familiar story of the rebels’ motivations and plans for the Rising, the reader is simply dropped into the fighting along the northern bank of the Liffey on April 24th 1916. A troop of lancers are shot up as they set out to investigate what is happening. The Volunteers shoot a number of unfortunate civilians who failed to stop at road blocks. Inquisitive DMP policemen who tell the insurgents to go home lest they be arrested are themselves taken prisoner. Twenty five year old Sean Houston and a handful of Volunteers begin a desperate three day battle with encroaching Dublin Fusiliers at the Mendicity Institute.

O’Brien notes that no one who has not been in a warzone can really explain what it is like. No doubt this is true, but the reader here gets a vivid picture of the hellish street by street fighting.

O’Brien notes towards the end of the book that no one who has not been in a warzone can really explain what it is like. No doubt this is true, but the reader here gets a vivid picture of the hellish street by street fighting. Civilians who rush for cover are gunned down. Friends who had been talking fall dead suddenly. Others are horribly wounded.

The insurgents of Easter Week are often described as ‘untrained’, but as O’Brien shows here, this was far from true. They had not been in combat before but had in fact been training for rebellion for months or even years. Many, as the British troops facing them found, were excellent shots. Facing them, there were some veterans, especially among the Dublin Fusliers, on leave from France, who knew how to use cover and to suppress targets by firepower and sustained relatively few casualties. By contrast, the South Staffordshire regiment, rushed over to Dublin out of basic training, did not even know how to load their weapons when they arrived in the city and O’Brien shows that a number of their casualties were self-inflicted.

Moreover, scores were shot down and 14 killed in their futile attempts to mount frontal assaults on rebel barricades on North King Street. These green soldiers, perhaps out of revenge, or perhaps due to orders to take no prisoners, killed 15 civilian men whom they found in the houses along the route of their advance. (See also the Irish Story article on the massacre).

Patrick Pearse formally surrendered on the Saturday of Easter week, but his order did not reach Ned Daly in the Four Courts until late the following day and the Volunteers around North King Street did not surrender, reluctantly, until the Sunday.

O’Brien argues that both the Volunteers and the British displayed more strategic ability in the fighting than they are usually credited with. The Volunteers’ positions were well sited to cause maximum enemy casualties while remaining in cover themselves. The British adapted to advancing behind armoured vehicles and burrowing through the walls of houses.

One must ask whether, from a British point of view, many of their casualties on North King Street were unnecessary

Nevertheless, one must ask whether, from a British point of view many of their casualties were unnecessary. Why go to the trouble of storming North King Street in particular when it could simply have been isolated and either starved or bombarded into surrender? And while the insurgents’ tactics were sound, there was still surely nothing strategic –i.e. war winning – they could have done while cooped up in isolated positions around the city? For this reason, the element of display and armed propaganda involved in the Easter Rising as well as its military details remains important.

Overall, along with O’Brien’s other books in this series, this is a very interesting piece of research giving us a ground level view of the week in which central Dublin became a warzone.