A Black and Tan Executed – The life and death of William Mitchell

The search for the short and tragic life of William Mitchell, Executed in Dublin in 1921. By DJ Kelly.

On Tuesday 7th June 1921, three men were executed at Dublin’s Mountjoy Gaol. This may have passed off as unremarkable, given that executions were coming thick and fast during the Irish War of Independence. No fewer than six men had been hanged at Mountjoy during the previous month, all of them Republicans. Indeed two of the men hanged on 7 June were also Republicans.

On that day, however, the third man taking the short walk through the red door of the hang house and into eternity was not. Thirty-three year old William Mitchell was a newly recruited constable in the Royal Irish Constabulary – a so-called Black and Tan. In fact, he was the only member of the British Crown Forces to be hanged for murder during that bitter struggle for Ireland’s independence.

THE BACKGROUND

At the height of the 1919-21 conflict, ambushes, abductions and killings were occurring almost daily and were perpetrated by both sides: the Irish Volunteers or Irish Republican Army and the Royal Irish Constabulary and British Army. It was a bloody war of reprisals, in which local magistrates and the constabulary were viewed as instruments of British repression in Ireland and, as such, were the targets of choice for the IRA. By the summer of 1920, almost one hundred members of the constabulary had been killed and a further five hundred had resigned, out of fear or conscience.

WHO WERE THE BLACK AND TANS?

By the autumn of 1920, constables were being recruited in Britain to bolster the ranks of the RIC. Contrary to popular myth, there is no evidence to suggest that these recruits included a greater number of criminals than any other police force before or since.

Anglo-Irish historian and journalist Brian Inglis’s retrospective description of them as ‘the sweepings of English gaols’ is wholly without substance. They were in fact ex-combatants, blooded and battle-hardened from the recent holocaust which was the Great War.

Most of them had been unable to find employment upon their return to the ‘Land fit for Heroes’ and so the chance to use their soldiers’ skills, at the generous rate of ten shillings a day, presented a golden opportunity in the post-war economic depression. Their hastily assembled, mis-matched uniforms of dark green police jackets and khaki army trousers led to the Irish populace dubbing them the Black and Tans – the name famously deriving from a pack of hunting hounds well-known in Limerick.

The newly arrived constables were posted to police barracks across Ireland to assist the regulars in maintaining the law. Without effective management however, they relieved their boredom, and doubtless also dulled the memory of their experience in the trenches, with excessive drinking and bad behaviour and soon gained a reputation for heavy-handed brutality and dishonesty.

Demobilised officers too were recruited from Britain and formed into a separate RIC Auxiliary Division. Known as Auxiliaries or ‘Auxies’ and intended initially to provide an officer cadre for these temporary men, they were instead deployed into self-contained local strike forces of about 100, often assaulting, abducting and killing suspects without due process of law.

All these new men, whether constable or Auxiliary, were referred to by the local population as ‘Tans’. Contemporaneous eye-witness accounts suggest that in fact the worst of the atrocities perpetrated by the temporary policemen were carried out by the tam-o-shanter wearing Auxiliaries. What is not widely known is that at least a quarter of the Tans were Irish or of Irish descent, for many Irishmen who had fought in the war had been demobilised in England and had remained there in vain hope of finding work.

WHO WAS MITCHELL?

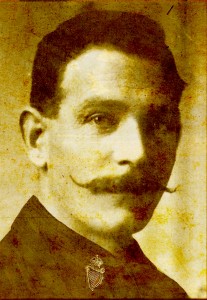

Very few accounts of the conflict mention Mitchell and those which do describe him, wrongly, as ‘English’. This paucity of information on him is forgivable however, since the official case papers were very difficult to locate. Identifying him from birth and census records also proved challenging. Two years of painstaking research eventually confirmed that William Mitchell too was an Irishman; a Dubliner.

Very few accounts of the conflict mention Mitchell and those which do describe him, wrongly, as ‘English’. This paucity of information on him is forgivable however, since the official case papers were very difficult to locate. Identifying him from birth and census records also proved challenging. Two years of painstaking research eventually confirmed that William Mitchell too was an Irishman; a Dubliner.

Born in the Montgomery district of North Dublin, then Europe’s largest red light district and most squalid slum area, Mitchell was the son of a south London-born professional soldier, a veteran of the Boer War, and a local Protestant girl. William Mitchell followed his father’s example and joined the army, serving King and Empire firstly in India and then in the trenches of the Western Front. Badly wounded at the Somme in 1918, he was invalided out of the army and soon found himself unemployed but with a young pregnant wife to support.

WHY DID HE HANG?

By the June 1921, 22 of the two dozen Republicans who were to die by official execution for their cause had been put to death. Mitchell’s execution was probably a gesture towards also punishing Crown force’s indiscipline at a time when negotiations fora truce were ongoing.

By the June 1921, 22 of the two dozen Republicans who were to die by official execution for their cause had been put to death. Thus far however, no Black and Tan had been hanged. Although there had been sufficient evidence to bring several Auxiliaries to trial for murder – one of them twice – the suborning and abduction of prosecution witnesses meant none of the accused felt the hangman’s noose. With the advent of the photo-journalist, the full attention of the world’s press was now focused on the conduct of the Tans and complaints were forthcoming from America and Australia. Other nations of the British Empire were watching the developments in Ireland with interest and indeed the British authorities began to sense that the truce in Ireland might spell the end of empire.

King George V himself had intervened, incensed at the treatment of the Irish people and demanding that Lloyd George’s government rein in their out-of-control pseudo-gendarmerie and effect at least a semblance of even-handedness in their application of the law. Then, in February 1921, in the quiet Wicklow town of Dunlavin, Robert Dixon, a local magistrate, was killed during the course of a robbery at his home.

The man suspected of the murder, Scots Temporary Constable Arthur Hardie, who was based at the Dunlavin police barracks, committed suicide before he could be brought to trial. His corpse was identified by members of the Dixon family as being the intruder who had shot the magistrate. Hardie’s fellow constable, William Mitchell, immediately fell under suspicion of being his accomplice in the robbery and was promptly arrested.

Under the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act, martial law had been imposed on most Irish counties, and so Mitchell was subjected to a court-martial – in effect a trial without jury. Whether Mitchell carried out the killing or indeed was even present when the robbery took place is disputable.

However, he and his Cork-born civil lawyer faced an intimidating battery of high-ranking military officers, each of them also a King’s Counsel. At the end of the proceedings, which lasted barely two days, and no witnesses having been called to speak in Mitchell’s defence, the British Judge Advocate General announced a ‘guilty’ verdict – a verdict against which there was no right of appeal.

William Mitchell went to the scaffold on 7 June 1921 still protesting his innocence and leaving his twenty-three year old widow and seven week old baby daughter to face destitution. His conviction and execution went a little way towards countering accusations of bias in favour of the Crown Forces. Hanged along with Mitchell that morning were Republicans Patrick Maher and Edmond Foley. They had been tried twice by civilian courts and acquitted each time of the murder of a policeman during an attempt to rescue an IRA man. Their third trial, a court-martial conducted like Mitchell’s trial without jury or the possibility of an appeal, also brought in a verdict more favourable to the British administration.

WHY HAS THIS STORY NEVER BEEN TOLD UNTIL NOW?

When I eventually tracked them down, the Mitchell files did not appear to have been opened since the 1920s, when it seems a half-hearted attempt had been made to weed them. I imagine this was during the hasty and disorganised departure from Dublin Castle of the outgoing British administration, at the time of the handover to the new Irish government.

When I eventually tracked them down, the Mitchell files did not appear to have been opened since the 1920s, when it seems a half-hearted attempt had been made to weed them. I imagine this was during the hasty and disorganised departure from Dublin Castle of the outgoing British administration, at the time of the handover to the new Irish government.

Eye-witnesses of that event reported the somewhat less than dignified evacuation of British officialdom; an evacuation in which van-loads, and even donkey cart-loads of documents were hurriedly removed from the castle and shipped to London. It is reported there was something of a paper trail left fluttering in the wake of the outgoing bureaucrats. Yet more paperwork was burned in the castle precincts during the dying days of the old régime.

Certain papers within the Mitchell file, annotated with blue pencil to highlight their importance, appeared to have been ear-marked for destruction. They had been unlaced from amongst the file contents, but were seemingly left tucked loosely within, probably by some harassed clerk. These papers contained clues as to why it was, when no Auxiliary was ever executed for the non-judicial killing of Irish citizens, the hapless Constable Mitchell was swiftly convicted and executed for a killing he may not have committed.

IS THIS THE END OF THE STORY?

That there was a political imperative behind the verdict in the Mitchell case is deducible from the files, as is the inescapable conclusion that the outcome of his court-martial was decided before the proceedings had even begun. My fascination with the theme of ordinary people thrust into extraordinary circumstances and finding themselves at the heart of great moments of history – Irish history in particular – led me to explore the life and death of William Mitchell.

That my enquiries with the National archives in both the UK and Ireland and the Irish General Records office all met with negative results initially presented an irresistible challenge. It seemed inconceivable that a man might be executed but no official record of his trial and execution remained. My interest piqued, I pursued my research until at last I succeeded in unearthing the case papers and trial transcripts, identified Mitchell’s improperly registered birth details and also located some of Mitchell’s living family members, who generously gave me much useful personal information and photographs of the man.

I decided to write the untold story of this tragic and forgotten man as a novel. In this way, I felt I could engage readers in the wider picture of Mitchell’s life and antecedents, as well as presenting the full facts of the case, thereby enabling readers to judge for themselves whether Mitchell’s execution was justified or whether this was a tragic miscarriage of justice. As Dublin formulates plans to commemorate a decade of centenaries marking the ‘Irish Revolution’ [1913-1923] and the long and painful birth of the Irish Republic, it will be chiefly the patriots and the politicians who will be remembered, not anti-heroes like Mitchell, who nonetheless played their part in these important events of history.

History has forgotten Mitchell. Few of his living descendants were even aware of his fate. His remains still lie within the precincts of Mountjoy Gaol along with those of forty other common criminals. However, his resurrection, in a real sense, is likely to cause controversy one day. There is a plan, albeit shelved temporarily in Ireland’s current economic climate, for the redevelopment of the prison site.

It is proposed that the ‘forgotten forty-one’ who are buried in the prison grounds be subsumed into the concrete of a retail park. However, these long dead forty men and one woman may yet rise up to embarrass the authorities. Irish press reports have surmised that no-one will protest or even be remotely interested if the only Black and Tan to be executed alongside Irish martyrs is not disinterred and given a Christian burial. I for one sincerely hope this is not the case.

_

Manchester-born Irish author DJ Kelly’s novel, ‘Running with Crows – The Life and Death of a Black and Tan’ [ISBN: 978-1-78299-154-0 FeedARead Publishing & PublishNation] is available in paperback from Amazon and all good bookshops and also in kindle edition.