“Shot down like a dog” The Finglas Riot of 1913

Christopher Lee on an episode of the 1913 Lockout. For more articles on the strike see here.

Hundreds of rioters advance on the two lone policemen in a darkened Finglas street, the only light coming from the windows of the pub.

The police retreat in the face of a barrage of stones and sticks hurled by the huge crowd; more stones are hurled at the pub shattering the plate glass windows. The two police take refuge around the corner of the pub but the crowd is still after them.

The police step out of the shadows, one with a revolver in hand, and order them back. They keep coming and one of the police drops to one knee and fires a volley of shots across the street. By the time the sound of the shots has died away the crowd have fled out of sight. In the now silent and deserted street lies a boy,face down on the road with a bullet in his back, another youth running to his aid.

Finglas in 1913

This was the scene 100 years ago on the night of September 16, 1913 in the normally quiet rural village of Finglas. During the Dublin Lockout Finglas briefly became a flash point in the farm labourers’ dispute. This event is not generally well-remembered today with only an occasional paragraph devoted to it in the books and articles on the Dublin Lockout and the farm labourers’ strike in County Dublin.

The events of the riot have been reconstructed from the extensive newspaper coverage of the time. But almost totally absent from these reports, the press being generally hostile to the strikers, are the voices of the farm labourers themselves

Modern Finglas, a vast sprawl of mostly public housing, has had more than its fair share of violence, social unrest and bad press over the last few decades, but it was not always like that. In 1913 Finglas was a rural village with a population of about 900 people a few miles north of Dublin. The main sources of employment were dairying and agriculture. In the era before widespread mechanisation agriculture required a substantial workforce. It was this group of farm labourers who became the focus of a movement to improve their pay and conditions.

In 1913 Finglas was a rural village with a population of about 900 people a few miles north of Dublin. The main sources of employment were dairying and agriculture. They went on strike for better wages and union recognition in 1913

In early 1913, James Larkin and the Irish Transport & General Workers Union (ITGWU) started a campaign to improve and standardise the pay and conditions of the County Dublin farm workers.The conditions of the farm labourers varied significantly from village to village and from farm to farm with each employer setting their own wages and conditions.

For example in Balbriggan farm labourers were paid 12s per week, in Balscadden 10s and in Gormanstown, 9s[1]. In addition to wages the labourers received perquisites, or ‘perks’ which also varied from employer to employer. An impression of a labourer’s ‘perks’ can be gained from the following example: “The lowest wage is 14s a week, but at that a man gets a free house. The average pay is 17s a week constant. Then we get £2 as harvest money, 3 tons of coal, half-ton of potatoes in the year, and milk twice a day.”[2]

Throughout June 1913 mass meetings in County Dublin led to large numbers of farm and transport workers joining the ITGWU and by the end of July, around 1000 labourers were on strike[3].

Rather than see their crops rot in the fields, the County Dublin Farmers Association agreed to the demands of the ITGWU on the 16th August 1913. The conditions the farm labourers had won were; a six-day week, a 12 hour day with 2 hours for meal breaks and a half day on Saturday. Their wages were set at 17s per week plus the usual perquisites, or 4s per day for casual labourers.[4]

However, it was to be a short lived victory for the ITGWU. By the end of the same week newspaper articles appeared suggesting that the agreement wouldn’t survive long, as both the labourers and farmers were dissatisfied with it[5].Many expected that they would soon be on strike again.

The Lockout begins in the city

Events in Dublin were soon to overtake the parties to the farm labourers’ dispute. William Murphy, President of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce and Chairman of the Dublin United Tramway Company, was a vehement opponent of Larkin, the ITGWU and a unionised workforce. By mid-August Murphy had sacked over 200 of his employees for refusing to resign their membership of the ITGWU.The situation quickly escalated with Larkin calling on the union membership to strike on the 26th August. However, Murphy refused to back down and replaced the strikers with ‘scab’ labour.

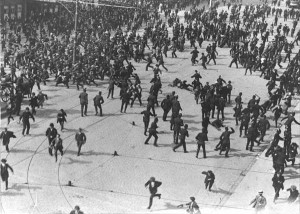

The dispute in Dublin rapidly became violent and culminated in the events of 30th August and “Bloody Sunday”. During the rioting and police baton charges on 30th August,James Nolan and John Byrne sustained head injuries from which they would later die, allegedly at the hands of drunken policemen.[6]An inquest into their deaths found that, despite their injuries being caused by police batons, the police were exonerated.Over the two days of rioting hundreds of people were injured, including many innocent bystanders.According to one report, “…over 450 people were treated in the various hospitals for scalp wounds.”[7] The actions of the police led to deep hostility toward them on the part of the strikers.

The Lockout began when the Transport union went on strike in protest at the sacking of their members and employers in response ‘locked out’ anyone who was a member or refused to sign a pledge not to associate with Larkin’s union. The dispute spread to north County Dublin in early September when the farmers there dismissed all members of the ITGWU

On September 3, William Murphy persuaded 400 of Dublin’s leading employers to support him in action against the ITGWU. They agreed not to employ any person who was a member of the union, sacking any who refused to give up their membership. On the 9th, the Dublin Building Trades Employers Federation also agreed to not employ members of the union, joining the ‘lockout’ of union members.On the 15th the Dublin Master Builders Association dismissed 3000 workers who had refused to resign their union membership[8].

On the 12ththe Co. Dublin Farmers Association decided to join the ‘lockout’and dismiss any farm labourer who chose to remain a member of the ITGWU. As a result, the labourers walked off the farms and went on strike. This was the catalyst which led to the riot in Finglas a few days later on Tuesday 16th September.

The riot in Finglas

The riot had a prequel in an attack on the farm of John Butterly, resident of Newpark, Finglas. Some of the labourers on Butterly’s farm had refused to join the strike and in retaliation strikers destroyed a field of Butterly’s cabbages and threw his agricultural tools and machinery into a drain.[9]The village must have remained tense as:

The riot had a prequel in an attack on the farm of John Butterly, resident of Newpark, Finglas. Some of the labourers on Butterly’s farm had refused to join the strike and in retaliation strikers destroyed a field of Butterly’s cabbages and threw his agricultural tools and machinery into a drain.[9]The village must have remained tense as:

“All day on Tuesday there was simmering unrest in the locality. Many agricultural labourers out of work owing to the strike congregated in the street, and there was shouting and marching, but no incident of particular note occurred.”[10]

Theriot in Finglas was sparked when it became known that a “scab” had been served drink in one of the local pubs

The situation in Finglas began to escalate when it became known that a “scab” had been served drink in one of the local pubs. A farm labourer by the name of Patrick Perry, from Finglas Wood, employed by Mr Craigie of Harristown, St Margaret’s, was served drink in the public house owned by Mrs Hannah Flood in the main street of Finglas (now the Drake Inn[11]). Perry was “…one of the few workmen in the district who had not joined the strike,…”[12].

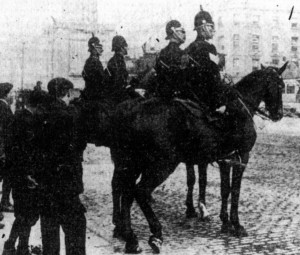

From around 3pm a number of men began picketing the pub and by 8pm an estimated 300 to 350 people had gathered in the street outside the pub, many of whom were boys;“The youngsters were very demonstrative…calling offensive names and shouting.”[13]There were three police stationed in Finglas, but only two on duty at the time, Sergeant John Brennan and Constable H. Barry, “…a young policeman of boyish appearance.”[14]In an attempt to protect the pub they stationed themselves outside it. Some reports suggested that members of the crowd were armed with “sticks and other weapons”[15] and another suggested they intended to loot the premises. [16]

After 10pm, when the other pubs in the village had closed, the crowd, many of whom, the police and press were later to allege, were drunk, became increasingly noisy and belligerent. Speeches were made by members of the crowd; Joseph Mackey spoke, saying that “Murphy was already beaten” and Owen Keane said to “stand by Larkin, that he was the man who would get them more wages, and if he were dead there would be others to take his place.” James Connell spoke, saying that “Healey of Clonmellon had locked out his men on a week’s notice.”[17]

James Brady made a speech denouncing the police, that “…the police in the city had murdered women and children.”[18]The police were later to allege that Brady’s speech contributed most to the subsequent events, that it was inflammatory and “calculated to stir up the crowd to acts of violence against the police”[19]. The crowd hoisted Connell on their shoulders and paraded down to the end of the village.

Two policemen were rushed and they opened fire on the crowd

It was during this interval that Sergeant Brennan and Constable Barry returned to the RIC barracks to arm themselves. Fearing the situation was deteriorating rapidly Sergeant Brennan directed Barry to arm himself with a revolver. They returned to the street outside the pub and not long after the crowd made its way back again.

At around 10.30pm the crowd began pelting the pub and police with stones.Stones shattered the plate glass windows of the pub and the police were forced to take refuge around the corner of the pub.The crowd advanced on the police accompanied by shouts of, “Go for them now, there are only two of them. Drive them to hell off the street. Let’s wipe them out”[20]. Sergeant Brennan reportedly said to Barry, “…they must do something to save themselves or they would be killed.”[21]

The police stepped out to confront the crowd and Sergeant Brennan ordered them to disperse, warning he would order Barry to fire. When the crowd continued to advance and was only five to seven yards away, Sergeant Brennan ordered Barry to fire over their heads. Constable Barry dropped to one knee and instead of firing over their heads, fired to one side, towards the other side of the street. Barry had fired four shots by the time Sergeant Brennan ordered him to cease fire, by which time the crowd had fled out of sight up the old North Road.

The shooting of Patrick Daly

As the crowd fled a youth by the name of Patrick Daly was seen to stumble and fall. Daly was seventeen years of age, the son of the local maternity nurse.[22] Another member of the crowd, a boy named Cummins, saw him fall and “…helped Daly over to where the police were standing, and pointed out to them that the youth had been shot. The policemen is alleged to have stated that only blank cartridge was used, and this Cummins answered by showing the hole in the boy’s clothing, about the middle of the back, through which the blood was oozing.”[23]

Despite their having shot the young man, both police returned to the barracks for their rifles before taking Daly to seek medical assistance.[24]The two policemen were later to claim that they only found Daly after they returned from their barracks.[25]It was now around 10.45pm and Sergeant Brennan was to later say that he saw James Brady again addressing the crowd[26], “…and that the demeanour of the mob was very menacing”[27].

The police took Daly to Dr D’Arcy Benson at Farnham House accompanied by seven or eight people who had been members of the crowd. While Daly’s wound was being dressed Dr Benson had to intervene to prevent the members of the crowd present from assaulting the police.[28]By this time Daly was semi-conscious and Dr Benson dispatched him in his own carriage to the Mater Misericordia Hospital in Dublin.

Seventeen year old Patrick Daly was shot in the back and badly injured as he ran away from the police.

In the meantime the crowd had reassembled and surrounded Farnham House. Groups had gathered at all the exits to the grounds and gathered large quantities of cobble stones and other missiles. One report stated of the police that “…if they confronted the infuriated crowd under the circumstances (they) would have been “torn to smithereens”.[29]

Sergeant Brennan and Constable Barry were unable or at least unwilling to attempt to leave Farnham House until around 11.30am the next morning when a car carrying four policemen arrived from Swords. [30],[31]A report on the situation in Finglas that morning stated that: “….the police, reinforced, are marching around in parties of four almost inviting a conflict.”[32]

Though Finglas remained quiet throughout the day large crowds gathered in the evening. This time however through the intervention of Rev. Philip Ryan there was no incident and the crowd dispersed at about 11pm.[33]

That same evening in Dublin, James Larkin took up the cause of young Patrick Daly. Addressing a crowd outside Liberty Hall, Larkin advised those present to be peaceable and quiet, that:

“The police were already responsible for the murder of their comrades, Byrne and Nolan, and only a few hours ago they shot down young Daly, at Finglas, like a dog. The people should not give any chance to the police who are thirsting to continue their murderous assaults.”[34]

In the earliest accounts of the riot in Finglas there were reports that Constable Barry was arrested following the shooting of Daly[35]. However, there is no mention of this in any of the subsequent reporting of the riot or the court appearance of the rioters. There was also mention that the two policemen attempted to break up the large crowd with a baton charge. Though it is not clear,it is possible that this is what actually prompted the crowd to attack them.

Patrick Daly was admitted to the Mater Misericordia Hospital and the next day Sir Arthur Chance, the chief surgeon of the hospital, operated on Daly to remove the bullet[36]. By the 19th September, Daly was reported to be recovering well.

Aftermath – the defeat of the County Dublin strikers

Finglas remained quiet throughout the remainder of September and there was no further unrest.In late September the labourers in County Dublin received some strike pay. The amount paid was very small and varied across locations, depending it was said, upon the strength of the local union branch. In the Swords area married men received 4s. to 3s. 6d. while single men received 2s, and others, nothing. In the Finglas area married men received 2s. to 3s. while single men received 1s. 6d. to 2s. Casual labourers received nothing.

By early November 1913, “privation and poverty” had forced the agricultural labourers back to work after giving up their union membership

In the Santry area married men on strike received only 2oz. tea, 2lbs. sugar and some other groceries with no cash[37]. The men on strike were told by the union to say they were actually receiving 10s in strike pay.[38]In a seemingly desperate move a group of strikers in Swords who had received no strike pay visited a number of shops demanding money from the owners[39].

In the interim farmers were taking steps to limit the impact of the strike. The introduction of the “free labour” movement into the Fingal area is credited to Mr Andrew Kettle Sr. of St. Margaret’s, who had been a founding member of the Land League and a close friend of Charles Parnell. Kettle brought in non-union labourers from counties not involved in the strike and employed them on his farm at Newtown, a short distance north of Finglas. Ten police were stationed in Newtown to provide protection for the farmers and the workers.[40]. As more farmers in Co. Dublin employed labour from other counties the prospects of those on strike began to look grim.

By early October there were reports of “privation and poverty” in Finglas, the wives of the striking labourers resorting to selling mushrooms and blackberries in an attempt to survive[41]. Faced literally with starvation, eviction from farmer-owned cottages and the approach of winter, some strikers began to return to work[42].

By early November,except for Swords, Kinsealy, and Clondalkin districts,the farm labourer strike was drawing to a close in County Dublin. Most of the labourers had already returned to work and the remainder were expected over the coming weeks[43].

However, even though the men of Finglas had mostly returned to work the authorities had not forgotten about them.Ten men were summoned to appear at Drumcondra Courthouse on 7th November 1913 charged with riot, unlawful assembly and assaulting the police.The defendants were: James Brady (age 22, Finglas), James Connell (age 30, Finglas), Joseph McKee (age 31, Finglas), Owen Keane (age 20, Tolka), Patrick Dunne (age 37, Dubber), brothers Thomas Cummins (age 22, Finglas) and Peter Cummins (age 20, Finglas), and brothers Patrick Brennan (age 23, Finglas), John Brennan (age 21, Finglas) and Charles Brennan (age 19, Finglas). All the defendants were described as “…men of respectable character.”[44]

The Magistrate who heard the inquest into the police shooting in Finglas commended the police officers for their actions, saying “…he had never come in contact with a set of circumstances that justified the police more in using deadly weapons..” the “…young officer had performed his duty in a most humane manner.”

The defence solicitor raised issues regarding the conduct of the police but chose not to pursue them.When Sergeant Brennan was giving evidence about the speeches made against the police, the defence asked if they said: “…something about halves of malt?” or “…anything reflecting on the temperance of the police?”.Sergeant Brennan denied any suggestion that the police had been drinking prior to the shooting of Patrick Daly, echoing the circumstance surrounding the death of James Nolan.

The defence pressed Sergeant Brennan to confirm that he had indeed put a junior constable who had been in the RIC only 2 years,in charge of the revolver. Sergeant Brennan was asked if he had ordered Constable Barry to go down on one knee and fire to one side of the crowd. Sergeant Brennan denied that he had, saying he ordered Barry to shoot over the heads of the crowd. He also denied that he had ever said the revolver had only fired blanks and stated that he had only seen Daly after returning from the police barracks.

On cross examining Constable Barry, the defence asked why he had disobeyed an order from a superior officer and not fired over the heads of the crowd. At this point the magistrate intervened, saying “…that such questions to a young officer, in the presence of the County Inspector, might prove very damaging to him.” Rather than press the point the defence responded that “…he would not in that case persist in the questions. The officer was an able young man and he had not the least desire to injure his prospects of promotion.”[45]This ineffectual display was the extent of the defence for the men aside from a suggestion that “The case, … was much ado about nothing.” and that the defendants should be given good behaviour bonds.

The prosecution felt that it was as serious case of riot as he had ever encountered and was glad the defendants had made no attempt to justify their actions. However he did agree that good behaviour bonds would be the most appropriate measure in the circumstances. The Magistrate ruled that as there had been no further trouble in the district and that the men were of good character, they would be placed on good behaviour bonds.

James Brady, James Connell, Joseph McKee and Owen Keane were bound to keep the peace for 12 months on a surety of £10 each; the remaining defendants were bound to the peace for 12 months on a surety of £5 each. As the final act of the hearing the Magistrate commended the police officers for their actions, that “…he had never come in contact with a set of circumstances that justified the police more in using deadly weapons..” and that the “…young officer had performed his duty in a most humane manner.”[46]

Post Script

I first encountered mention of the 1913 Finglas riot while researching the history of my partner’s grandfather, Francis (“Terry”) Brennan of Finglas. It was particularly interesting when I found that three of the defendants in the resulting hearing were Francis’ older brothers, Patrick, John and Charles Brennan. Francis was 14 years old at the time and I imagine that he would have been one of the many “demonstrative” boys who made up the crowd, following his older brothers in hurling abuse and stones at the police.

Charles later enlisted in the British army and fought at Gallipoli, in Libya and at the Battle of the Somme, being wounded and discharged in 1917. ‘Terry’ joined the IRA in 1917 and went on to serve in the War of Independence and Civil War. He was sentenced to death when captured fully armed as a member of an anti-Treaty flying column. The sentence was later commuted to 7 years imprisonment. In 1923 he spent 22 days on hunger strike. He was released from internment in July 1924 and returned home to Finglas where he remained until his death in 1955.

Christopher Lee is an independent Irish researcher living in Australia.

Bibliography

Coyle, E. A., 2005. Larkinism and the 1913 County Dublin Farm Labourers Dispute. Dublin Historical Record, 58(2), pp. 176-190.

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. “No Starvation” – Coal and Bread for Strikers. Freeman’s Journal, 18 September, p. 8.

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. Bloodshed in Dublin. Freeman’s Journal, 1 September, p. 7.

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. Commission Cases – Swords Troubles. Freeman’s Journal, 25 October, p. 8.

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. Complaints on Both Sides. Freeman’s Journal, 12 September, p. 2.

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. Condition of Patrick Daly. Freeman’s Journal, 22 September, p. 9.

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. Finglas Disturbance. Freeman’s Journal, 19 September, p. 7.

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. Finglas Sensation – Ten Men Summoned. Freeman’s Journal, 7 November, p. 11

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. Lucan Lock-out. Freeman’s Journal, 21 October, p. 8.

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. Outrages Near Finglas. Freeman’s Journal, 18 September, p. 8.

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. Saturday Night Scenes – Repeated Baton Charges. Freeman’s Journal, 1 September , p. 7.

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. Strike Riot at Finglas Village. Freeman’s Journal, 18 September, p. 7.

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. Strong Criticism of the Police. Freeman’s Journal, 1 September, p. 8.

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. Swords Glass Breaking Case. Freeman’s Journal, 13 October, p. 5.

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. The Farm Disputes. Freeman’s Journal, 11 November, p. 8.

Freeman’s Journal, 1913. The Finglas Riot. Freeman’s Journal, 8 November, p. 8.

Irish Independent, 1913. County Commission – Farm Strike Charges. Irish Independent, 25 October, p. 7.

Irish Independent, 1913. Dublin Farm Hands. Irish Independent, 8 October, p. 5.

Irish Independent, 1913. Farm Hands Return. Irish Independent, 10 October, p. 5.

Irish Independent, 1913. Farmers and Striker. Irish Independent, 3 November, p. 5.

Irish Independent, 1913. Farmers and Strikers. Irish Independent, 31 October, p. 5.

Irish Independent, 1913. Harassed Farmers – Unrest in North Dublin. Irish Independent, 18 September, p. 5.

Irish Independent, 1913. Items of the Unrest. Irish Independent, 18 September, p. 7.

Irish Independent, 1913. Riot at Finglas. Irish Independent, 18 September, p. 5.

Irish Independent, 1913. Sequel To the Finglas Riot. Irish Independent, 7 November, p. 5.

Irish Independent, 1913. The Co. Dublin Strikes – Nearing the End. Irish Independent, 11 November, p. 6.

Irish Independent, 1913. The Finglas Riot – Two Policemen in Peril. Irish Independent, 8 November, p. 7.

Irish Independent, 1913. The Injured Boy Daly. Irish Independent, 19 September, p. 6.

Irish Independent, 1913. The Labourer’s Strike in Co. Dublin. Irish Independent, 19 September, p. 3

Irish Times Weekly, 1913. Young Man Shot at Finglas. Irish Times Weekly, 27 September.

Irish Times, 1913. The Finglas Riot – Fierce Attack on the Police. The Irish Times, 8 November , p. 5.

Poverty Bay Herald, 1913. The Plight of Dublin. Poverty Bay Herald, 22 October, p. 4.

Sunday Independent, 1913. Sunday Independent, 21 September, p. 8.

The Sydney Morning Herald, 1913. Disorder in Dublin. Renewed Outbreaks. The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 September, p. 9.

The West Australian, 1913. Dublin Disturbances. The West Australian, 19 September, p. 7.

Ulster Herald, 1913. Strike Riots in Dublin. Ulster Herald, 6 September, p. 7.

Yeates, P., 2001. Lockout: Dublin 1913. s.l.:Palgrave Macmillan.

Yeates, P., 2001. The Dublin 1913 Lockout. History Ireland, 9(2), pp. 31-36.

Yeates, P., n.d. Lockout Chronology 1913 – 1914.

[1]Freeman’s Journal, 23 August 1913, Page:8

[2] Irish Independent, 18 September 1913, Page:5

[3]“Larkinism and the 1913 County Dublin Farm Labourer’s Dispute” Eugene A. Coyle, Dublin Historical Record, Vol. 58, No. 2 (Autumn, 2005), pp. 176-190

[4] Irish Independent, 18 August 1913, Page:6

[5] Freeman’s Journal, 23 August 1913, Page:8

[6] Captain Robert Monteith: writing in “Casemate’s Last Adventure”.

[7] Ulster Herald, 6 September 1913, Page:7

[8] Sunday Independent, 21 September 1913, Page:8

[9] Freeman’s Journal, 18 September 1913, Page:8

[10]Freeman’s Journal, 18 September 1913, Page:8

[11] Also known as the top Flood’s, as opposed to the bottom Flood’s which were both owned by the Flood family. The bottom Flood’s was later to become the Bottom of the Hill pub. The Drake Inn was closed in December 2008.

[12]Freeman’s Journal, 18 September 1913, Page:8

[13]Freeman’s Journal, 18 September 1913, Page:8

[14]Freeman’s Journal, 18 September 1913, Page:8

[15] Irish Independent, 18 September 1913, Page:5

[16]Freeman’s Journal, 18 September 1913, Page:8

[17] Freeman’s Journal, 8 November 1913, Page:8

[18] Freeman’s Journal, 8 November 1913, Page:8

[19] Irish Independent, 18 September 1913, Page:8

[20] Irish Times, 8 November 1913, Page:5

[21] Freeman’s Journal, 8 November, 1913, Page:8

[22]Freeman’s Journal, 18 September 1913, Page:7

[23] Freeman’s Journal, 18 September 1913, Page:7

[24]Freeman’s Journal, 18 September 1913, Page:7

[25] Irish Independent, 8 November 1913, Page:7

[26] Irish Times, 8 November 1913, Page:5

[27] Freeman’s Journal, 18 September 1913, Page:7

[28] Irish Times Weekly, 27 September 1913.

[29]Irish Times Weekly, 27 September 1913..

[30] Freeman’s Journal, 18 September 1913, Page:7

[31] The shot which struck Daly was reported to have ricocheted from the wall of Heery’s public house, which was opposite Flood’s pub. Heery’s later became the Duck Inn which closed in 1976. Daly was hit in the back, not in the leg as stated by Eugene Coyle in “Larkinism and the 1913 County Dublin Farm Labourer’s Dispute”, Dublin Historical Record, Vol. 58, No. 2 (Autumn, 2005), pp. 176 – 190. Coyle also names the doctor who treated Daly as “Dr. Darcy Benton” and writes that the two police in Farnham House could not leave until “…a convoy of armed RIC men arrived to rescue them, that order was restored in the village.”

[32] Poverty Bay Herald, 22 October 1913, Page:4

[33] Irish Independent, 19 September 1913, Page:6

[34] Freeman’s Journal, 18 September 1913, Page:8

[35] The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 September 1913, Page:9

[36] Irish Independent, 19 September 1913, Page:6

[37] Irish Independent, 25 September 1913, Page:7

[38] Irish Independent, 8 October 1913, Page:5

[39] Irish Independent, 25 September 1913, Page:7

[40] Irish Independent, 3 November 1913, Page:5

[41]Irish Independent, 1 October 1913, Page:5

[42]Irish Independent, 1 October 1913, Page:5

[43] Freeman’s Journal, 11 November 1913, Page:8

[44] Irish Independent, 8 November 1913, Page:7 (some ages are approximate based upon 1911 Census)

[45]Irish Times, 8 November 1913, Page:5

[46] Irish Times, 8 November 1913, Page:5