“The principal rallying-ground for the Larkinites” – The Swords Riot of 1913

Christopher Lee, author of a previous article on Finglas in the Lockout, looks at the great strike of 1913 in the County Dublin village of Swords

Windows up and down the darkened street are smashed by the rioters, a hail of stones and bottles shattering every window in the police barracks. A line of police advance into a barrage of bottles and stones, some felled by the projectiles as they move on the crowd; suddenly the police surge forward, batons raised, swinging as they wade into the milling, surging crowd of men…

These scenes were not played out in the streets of Dublin but in the rural village of Swords on the night of October 9th, 1913.It is not widely appreciated the violence associated with the Dublin Lockout was not confined solely to Dublin City. Striking farm labourers from the Swords district also took part in the violence in Dublin, travelling into the city to take part in demonstrations. Throughout late 1913 the village of Swords and surrounds witnessed scenes of rioting, intimidation, vandalism and violence and hosted perhaps the largest police contingent outside Dublin.

During the farm labourers’ strike and Dublin Lockout, Swords was a stronghold of the Irish Transport & General Workers Union (ITGWU) in rural County Dublin. The village was described in contemporary newspapers as “…the principal rallying-ground for the Larkinites” and the “…centre of the trouble”. [1], [2] Frank Moss was the union organiser for the Swords district for the duration of the farm labourers’ dispute and Dublin Lockout and was instrumental in making the farm labourers of the area the most heavily unionised and militant in County Dublin.

Roots of the Dispute in North County Dublin

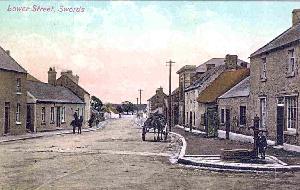

The farm labourers’ dispute had its roots in a campaign launched in early 1913 by James Larkin and the ITGWU to improve the pay and conditions of the County Dublin farm labourers. In 1913 Swords was a rural village in North County Dublin with a population of around 900 people. The main sources of employment were dairying and agriculture, which, before the adoption of mechanisation, required a substantial labour force.

Throughout June 1913, mass meetings in Swords, Clondalkin, Lucan, Howth and Blanchardstown enrolled large numbers of farm labourers and transport workers into the ITGWU. The Swords branch of the ITGWU established its headquarters in a house in the main street of the village. The strikers christened the house “Liberty Hall” in emulation of the ITGWU building in Dublin. Frank Moss would frequently address gatherings of strikers in the street from an upstairs window of the house.[3][4]

Just before the lockout the ITGWU had established itself among farm labourers in North County Dublin and forced several concessions from the farmers there.

The County Dublin Farmers Association opposed the industrial campaign as every farmer and landholder set their own wages and conditions for their workers meaning labourers in different areas could be paid different wages for the same work. The demands of the ITGWU and farm labourers were for higher wages and uniform pay and conditions while retaining all of the workers’ existing perquisites, or ‘perks’.

In response to opposition from the County Dublin Farmers’ Association, by the end of July around 1,000 labourers were on strike with about 600 in the Swords district alone.[5] By August, even though the situation in Swords remained peaceable, the large and enthusiastic demonstrations conducted by the strikers prompted the authorities to station fifty Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) policemen in the town. [6] A report stated that “Beyond cessation of work no trouble has been caused”.”[7] and “…a police constable stated that peaceful picketing was going forward.”[8]

On 16th August 1913, the County Dublin Farmers’ Association, rather than see their crops rot in the fields, capitulated to the demands of the ITGWU. The conditions the farm labourers had won were a six-day week, a 12 hour day with two hours for meal breaks and a half day on Saturday. Their wages were set at 17s per week plus the usual perquisites, 4s per day for casual labourers and 1s 6d a day, or 9s a week, for women.

Despite this victory the farm labourers were about to become embroiled in the escalating strike in Dublin City. Many farm labourers would soon find themselves on strike again and unable to benefit from the higher wages they had just won.

Swords and the Lockout

In Dublin, William Murphy, President of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce and Chairman of the Dublin United Tramway Company, refused to allow any of his employees to remain members of the ITGWU. After issuing an ultimatum to his staff he dismissed any who refused to resign their union membership. In response, on 26th August, James Larkin, perhaps emboldened by his victory over the County Dublin Farmers’ Association, called on the ITGWU membership to strike.

The events of 29th and 30th August, which culminated in “Bloody Sunday”, hardened the attitudes of both strikers and employers. The indiscriminate police violence left at least two people dead and hundreds of strikers and innocent bystanders injured.

William Murphy increased the pressure on Larkin and the ITGWU by employing non-union labour to replace the strikers and on 3rd September organised 400 of Dublin’s largest employers to dismiss or ‘lock out’ any employee who was a union member.

On 12th September, the County Dublin Farmers Association, at the urging of William Murphy, decided to join the ‘lockout’, going back on their 16th August agreement with the farm labourers. The farmers threatened to dismiss any farm labourer who refused to resign their union membership.

In September 1913 the farmers threatened to dismiss any farm labourer who refused to resign their union membership

As a result, farm labourers across County Dublin walked off the farms and went on strike. Over the following weeks the Swords farm labourers, about 300 of whom were on strike, spent“…their time in going through the district on their bicycles, making things…unpleasant…for those members of the union who are still at work.”[9]

The strikers in the Swords district began stopping carts of produce driven by non-union or ‘scab’ workers on their way to the Dublin markets. As well as blocking ‘scab’ labour, this was a form of economic warfare against the farmers, denying them the opportunity to sell their produce and harming their incomes. This, combined with the withdrawal of labour, led to shortages of fresh milk, potatoes and vegetables in Dublin and drove up the price of what was available.

The unintended consequence of the action against the farmers was to increase the hardship for those on strike in Dublin by forcing up food prices.

By mid-September the price of “..carrots, lettuce, and other descriptions of garden produce had advanced fully 50 percent.”[10] The unintended consequence of the action against the farmers was to increase the hardship for those on strike in Dublin. The workers on strike in Dublin were unable to pay the rising prices; “To the poor, potatoes are now at a price beyond their reach. This fact combined with the dearness of coal necessitates the use of bread and tea alone as the general food of the families of the unemployed and very poor.”[11]

‘Rowdyism’ – the first clashes in Swords

On Monday, 15th September, a gathering of striking farm labourers in Swords very nearly turned violent. Around 300 men, half of whom had reportedly been drinking heavily, paraded around the village until late in the evening, singing and shouting.

The crowd was very hostile to the police and the eight or nine police present were “…mobbed and shuffled off the footway.” The officer in charge ordered the police back to barracks “…amid the jeers and insults of the mob…” as he was concerned, if the situation escalated and the crowd “…persisted in their provocative conduct…firearms or batons would have to be produced…”.[12]

The crowd sought another outlet for its anger and marched to Kinsealy to attack the cottage of a farm worker who had not gone on strike. The cottage was guarded by two police who were powerless to stop the large crowd from stoning the cottage and smashing all the windows. The crowd remained there for half an hour, shouting and dancing to the music of a “…ragtime pipe and drum band…” which had accompanied the demonstration.[13]

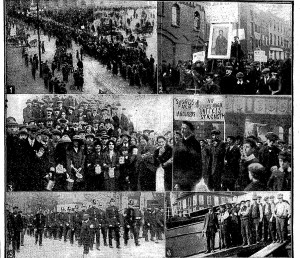

On September the 15th there were tense confrontations between police and strikers in Swords, and the following week many Swords workers were involved in rioting in Dublin city

The next night, 17th September, strong police reinforcements in Swords “…prevented a repetition of the previous night’s rowdyism.” The strikers instead marched out to attack the same cottage in Kinsealy but were met there by twenty police armed with revolvers. The strikers “…discreetly retreated back to Swords.”[14]

The 17th September was the same night a riot took place in Finglas. Striking farm labourers began picketing a pub where a ‘scab’ worker had been served a drink. Later that night the pub and police were pelted with stones resulting in accidental shooting by the police of Patrick Daly, a 17-year-old local boy who had been a member of the crowd.[15] There were only two policemen on duty in Finglas that evening rather than the usual three or four. It is possible the others had been sent to reinforce Swords, leaving the remaining police in a precarious position when trouble started in Finglas.

On 18th September, 300 strikers, accompanied by the Swords pipe and drum band, marched into Dublin to take part in labour demonstrations.[16] The Swords strikers would have been present to hear James Larkin’s speech at Liberty Hall advising those present to be peaceable and quiet:

“The police were already responsible for the murder of their comrades, Byrne and Nolan, and only a few hours ago they shot down young Daly, at Finglas, like a dog. The people should not give any chance to the police who are thirsting to continue their murderous assaults.”[17]

However, the Swords farm labourers were far from peaceable and quiet. Prior to the riot in Swords the farm labourers gave a clear indication of their willingness to engage the police in battle.

On 21st September the Swords strikers were involved in a serious riot in Dublin. Over 200 farm labourers marched into Dublin to participate in demonstrations at Croydon Park, the pro-employer Irish Independent commented, “The contingents were from the Coolock and Swords districts and their demeanour was generally aggressive.” [18]

At around 5pm, returning from the rally, strikers attacked trams of the Dublin United Tramway Company, which were driven by ‘scabs’. The farm labourers, other strikers, and “Girls, many of them of a low type…” attacked trams on North Strand Road, subjecting them to a “…fierce fusillade of stones, bottles and sticks.”[19]

As the police moved to make arrests they were pelted with bottles and stones. While parts of the large crowd of strikers coming from Croydon Park battled the police in Lombard Street and Townsend Street, in North Clarence Street the farm labourers bombarded the police with bricks from the ruins of two demolished houses.[20]

The police conducted a number of baton charges but the strikers would disperse and regroup in the side streets, attacking the police from all sides until they retreated. One policeman commented to the newspapers, “The remarkable thing about it, said this officer, was that the rioters seemed determined to fight. They stood their ground for a while, and used such ammunition as was ready to their hand. Stones, half bricks, bottles, iron nuts were sent whizzing through the air, and many persons were injured.”

Eventually the strikers were dispersed by repeated police charges, leaving many injured on both sides. Despite being beaten back, the Swords farm labourers had clearly demonstrated they were not afraid to take on the police.

The Swords strikers complained that the Dublin newspapers had misrepresented them. They refuted claims that, “…pandemonium prevails at Swords by night, and that “terrorism” is regularly practiced both at Swords and Kinsealy.” The strikers countered “…the police authorities agree with them – that they have never done anything worse than march through the town with the local fife and drum band; that in every speech made by a labour man in the district the policy of non-interference was advocated above all things…” They also claimed the farmers’ insistence on police protection for workers and carts was part of a campaign to “…discredit the strikers in the eyes of the public.[21]

September 1913 – The farmers fight back

In late September the farmers began to organise themselves to get their harvests in despite the farm labourers strike. One of the first such efforts was made on the farm of Charles Kettle, Kilmore Cottage, Artane.

Around twenty farmers, including several Justices of the Peace and gentlemen, gathered in around sixteen acres of corn. Despite being “…unused to bearing the heat and burden of the day, they all gave a marvellously good account of themselves…”.[22] The newspaper patronisingly suggested the gentlemen labourers “…actually taught lessons in sustained effort to the groups of strikers who picketed the place during the progress of operations.”[23] A plan by the Swords strikers to march out to picket in strength the next day fell apart when they were denied use of the drum of the Swords band.[24]

The farmers cooperated in bringing in ‘scab’ workers to get in the harvest in North County Dublin in late September 1913 – a tactic which upped the violence of the dispute there.

It was also in late September the striking labourers in County Dublin received some strike pay. The amount paid was small and varied across locations, depending it was said, upon the strength of the local union branch. Illustrating this very point, union members in Swords received around double the strike pay, 4s to 3s 6d, of those in Finglas, while those in Santry received only food aid.[25] In a seemingly desperate move, a group of strikers in Swords who had received no strike pay visited a number of shops, demanding money from the owners.[26]

Throughout late September and early October the strikers, led by Frank Moss, began to take a harder line with ‘scabs’ and non-union members and there were a number of incidents of violence and intimidation. Several incidents occurred when it became known pubs in Swords were serving drink to ‘scabs’.

On Saturday night, 27th September a group of strikers forced a ‘scab’ to leave a pub in the main street of Swords. Once outside the group attacked the man, who was rescued by the police, his attackers managing to escape.[27] In other cases Frank Moss avoided violent confrontation by ordering all union members to boycott an offending pub. Despite the hardening attitude, when union members attempted to drag a ‘scab’ out of a pub, Frank Moss stepped in to prevent violence, ordering them to leave him alone.[28]

On 1st October, the day of the monthly Swords fair, Frank Moss and the striking farm labourers intended to hold a demonstration in the main street. Moss intended to have the demonstration accompanied by the local band. However, the band instruments were owned by the local branch of the United Irish League – the grassroots organisation of the Irish Parliamentary Party – which in turn was controlled by the farmers.[29]

After some difficulty gaining access to the bandroom, the strikers were preparing to start their demonstration when a large body of police descended upon them. District Inspector Dowling informed the strikers “…if they brought the band on to the street he would be obliged to treat them as an illegal assembly, and disperse them by force, because their presence in the fair would inevitably provoke a conflict with the farmers.”[30] Finding themselves surrounded by the police and prevented from holding the planned demonstration, the strikers held their rally in the bandroom hall.[31]

Despite Moss’ previous statements of non-interference, rumours began to circulate that livestock being driven to market in Dublin by ‘scabs’ would be turned back by the strikers around Swords.[32] Patrols of police began escorting the cattle drives to Dublin. While groups of strikers were encountered, perhaps due to the police presence, they didn’t attempt to interfere with the herds.[33] However, this state of affairs would not last.

A newspaper report from early October stated the Swords strikers’ “…attitude had become more and more threatening...”[34]

On Wednesday evening, 9th October, Frank Moss addressed a crowd of strikers who had gathered to receive strike pay and provisions. Moss told the crowd “….that they had been “keeping too quiet in Swords” and that he himself had been too quiet during the strike there.”[35] True to his word, things would change that very night.

October 9th 1913, the Riot in Swords

At about 10pm that evening, a herd of sheep and a large herd of cattle were being driven through Swords with a police escort.[36] As they arrived at the turnpike at the southern end of the main street of the village, a group of strikers drove the animals back up the main street in confusion, chasing and scattering them in the darkness.

On October 9th, serious rioting erupted in Swords when police arrested a striker who had helped drive off a herd of farmers’ cattle.

The men driving the herds alerted the police and District Inspector Dowling accompanied by five or six police helped gather the scattered stock. The herds were again driven back through the village only to be met once more by the strikers who scattered them again. The police and drovers were pelted with stones and bottles and in the noise, darkness and confusion of men, cattle and sheep running in all directions, the handful of police could not control the situation.[37]

With the help of a strong light mounted on a police bicycle, the police managed to identify and arrest one man, Christopher McKittrick.[38] Leaving two constables to manage McKittrick, a sergeant cycled to the police barracks for reinforcements. As the police escorted McKittrick back to their barracks at the other end of the main street, they encountered a crowd of about 100 strikers near “Liberty Hall”.

Seeing McKittrick in the hands of the police the crowd blocked them“…forming four deep across the street at “Liberty Hall”.”[39] John Dardis, Michael Dempsey and Timothy White rushed forward, took hold of McKittrick and refused to let him go, Dardis stating he was “…a picket of the Transport Union and would not let the prisoner pass until they knew what he was arrested for.”[40] Patrick Rourke, who was “…in a fighting attitude, and very excited, shouted: “Lads, rush them!”[41]

Three hundred strikers chased the police out of the village for a time but were eventually dispersed by two baton charges.

At this point the sergeant returned with five police officers and as the other police assisted in dragging McKittrick from the crowd, he arrested Rourke. As the police retreated towards their barracks with the two prisoners they were showered with bottles and stones, all the while accompanied by shouting and booing.

The striking farm labourers were now left in control of the main street of the village and, following the retreating police, attacked the barracks. The barrack windows were smashed by a hail of stones and bottles after which the strikers attacked the shops of those owners known to be sympathetic to the farmers and police.[42] During these wild, chaotic scenes even a window in “Liberty Hall” was smashed. It was during this wave of attacks on shops that Frank Moss was alleged to have smashed the window of McGonagle’s sweet shop, opposite “Liberty Hall”

In the meantime the police had gathered reinforcements and District Inspector Dowling, with around thirty police officers, moved in to break up the riot. As the police approached the strikers gathered outside “Liberty Hall” they were subjected to an intense barrage of bottles and stones, severely injuring several of them. At this point, District Inspector Dowling “…finding that all peaceable means of dispersing the mob were of no avail…” ordered a baton charge, scattering the crowd and injuring many of the strikers. A short time later the crowd reassembled but was dispersed by another baton charge.[43]

The police remained on the streets for the rest of the night to prevent any further outbreak of violence and to ensure herds of cattle made it through the village safely. The local doctor and nurse were busy until late in the night tending the injured strikers.[44]

The following evening saw a tense calm descend over Swords. There were rumours that the strikers were going to take revenge upon the police. A statement was made during the day by a union official, presumably Frank Moss, “…that the peaceful attitude by the men heretofore could no longer be adhered to…”.[45] Police reinforcements had arrived in the village, bringing the total up to seventy officers. Instead of sending them on their usual patrols, District Inspector Dowling kept them in the barracks, ready to deal with trouble at a moment’s notice.

As night fell groups of strikers were seen carrying fresh-cut sticks.[46] However, by 10pm, Swords remained quiet, leaving the police perplexed as to the whereabouts and intentions of the strikers.[47] It is possible many of the strikers, injured in the previous night’s baton charges, were in no condition or mood to take to the streets again. Also, it could be said, the strikers were sensible enough not to face a sizeable body of police who were clearly expecting and prepared for trouble.

The following day additional police reinforcements arrived in Swords bringing the total available to around eighty officers, a substantial police presence and possibly the largest police contingent stationed outside of Dublin during the lockout. This police presence is a testament to how seriously the authorities took the Swords strikers who by this stage numbered about three hundred in total.

Trial and punishment

The morning after the riot, at a special sitting of the magistrate’s court, Christopher McKittrick and Patrick Rourke were charged with rioting and assaulting the police. While both were found guilty, Rourke was remanded in custody but McKittrick was bound to keep the peace on a surety of £5, roughly six weeks wages for a farm labourer.[48]

At 4am on 16th October, the police moved to arrest John Dardis, MichaelDempsey, Timothy White and John Connor. Having been taken from their beds, they faced the Swords Magistrates Court that morning. Patrick Rourke, who had been in custody since 9th October, joined them in the dock. Despite the prisoners having no defence representation the hearing went ahead. They were charged with having:

“…unlawfully, tumultuously and riotously, with other persons to the number of about 100 assemble to the disturbance of the public peace, and while so assembled did unlawfully attempt to forcibly rescue one Christopher McKittrick from legal custody and arrest, and unlawfully obstruct certain constables of the RIC while in the execution of their duty.”[49]

Dardis, Dempsey, White and Rourke were refused bail and remanded in custody to face trial at the County Commission, a special court established to hear cases arising from the Dublin Lockout. Connor was released, but obliged to pay a good behaviour bond of £5. At the County Commission trial in late October, the court found John Dardis “…was the originator of the whole business.” and sentenced him to six months in prison. Patrick Dempsey was sentenced to four months, Patrick Rourke to three months, while Timothy White was found not guilty and released.[50]

Frank Moss faced trial in late October, charged with three separate acts of intimidation and with smashing the window of McGonagle’s sweet shop during the riot. At the start of the trial, Moss’ defence suggested any of the magistrates who had a personal interest in the progress of the farm labourers’ strike, should stand aside and take no part in the hearing. However, despite many of them being farmers and land owners, none of the magistrates stood aside and the defence council could only lodge a formal protest.

One of the charges against Moss was he intimidated a union member, James Lawless, by spilling the man’s drink. Lawless had been drinking in a pub when Moss demanded all union members leave because ‘scabs’ were being served there. When Lawless told Moss he would leave when he finished his drink, Moss took the drink from him and spilled it, both men leaving together. Even though Lawless told the court he had no problem with Moss spilling his drink, Moss was found guilty of intimidating him. Moss was also found guilty on the other two charges of intimidation and sentenced to three months imprisonment, with hard labour.[51]

While in Mountjoy Prison, Moss went on hunger strike and in response the prison authorities force-fed him.[52] Upon completing his sentence he was then tried on the charge of smashing McGonagle’s window, found guilty and sentenced to a further fourteen days in prison.[53] Despite his solicitor having lodged an appeal following his conviction on 24th October 1913, due to a supposed administrative error, Moss’ appeal was not heard until June 1914, when all charges were dismissed.[54] This was a meaningless gesture on the part of the authorities, as Moss had already spent four months in prison.

The defeat of the Swords strike

Throughout late 1913, the farmers took steps to break the power of the strikers by turning to the use of “free labour”, non-union labourers, some brought in from other counties. The introduction of “free labour” into County Dublin is attributed to Mr Andrew Kettle Sr. of St. Margaret’s. Despite their having to live and work under police protection, the use of non-union labour by farmers spread quickly.[55] Adding to the pressure on the strikers, many in the Swords district, including the occupants of “Liberty Hall” and John Dardis, were evicted from their houses by their farmer landlords.[56] By early October, faced literally with starvation, eviction and the approach of winter, strikers began to return to work.[57]

By the end of 1913, the strikers in North County Dublin had been forced back to work by starvation. Some union members were never taken back by their employers.

However, some farmers refused to take their former employees back, despite the labourers offering to do so on the farmer’s terms and asking for reinstatement “…under any circumstances…”.[58] As a result, the wives, mothers and daughters of the strikers in the Swords district, in an effort to put food on their tables, worked picking harvested potatoes from the fields.[59] The women were paid 2s a day, which, while it was less than the 4s paid to casual men, was still more than the 1s 6d which had been agreed for women under the 16thAugust agreement with the County Dublin Farmers Association.[60]

By February 1914, there were still around 230 unemployed members of the ITGWU in Swords unable to return to work as “…their positions have mostly been filled by “free” labour.”[61]

In desperation, many unemployed farm labourers took the jobs of Dublin workers who were on strike, becoming the ‘scabs’ they had previously despised.[62] Officials of the ITGWU used the strongest language to condemn the labourers who sought work in Dublin:

“The labourer who would come in to take a striker’s job was worse than Judas, for whereas Judas got thirty pieces of silver for his dirty job, they would only get twenty shillings. Judas as they all knew, afterwards hanged himself, and there would not be enough rope in the whole County Dublin to hang the labourers who attempted to act Judas on their fellow workers in the city.”[63]

Like the riot in neighbouring Finglas a month earlier, the riot at Swords did not affect the overall course of the strike. With the introduction of non-union labour into County Dublin the striking farm workers faced starvation, eviction and permanent unemployment. By late 1913 the strike had virtually collapsed and many of the striking farm labourers involved in the Swords riot had been arrested, imprisoned or evicted from their homes.

The defeat of the farm labourers and the strike in Dublin left many men unemployed, homeless and destitute. However, during the second half of 1913, the Swords farm labourers, under the direction of Frank Moss, were among the most militant and belligerent of James Larkin’s followers in County Dublin, making Swords “the principal rallying-ground for the Larkinites”.

References

[1] Irish Independent, 18 September, 1913, Page: 5

[2] Irish Times, 6 December, 1913, Page: 4

[3] Irish Times, 25 October, 1913, Page: 9

[4] The location of the Swords “Liberty Hall” was on the eastern side of the Main Street, roughly half way down, opposite the site of McGonagle’s sweet shop.

[5]“Larkinism and the 1913 County Dublin Farm Labourer’s Dispute”, Eugene A. Coyle, Dublin Historical Record, Vol. 58, No. 2 (Autumn, 2005), pp. 176-190

[6]Freemans Journal, 16 August, 1913, Page: 18

[7]Freemans Journal, 16 August, 1913, Page: 18

[8] Irish Independent, 16 August, 1913, Page: 9

[9] Freeman’s Journal, 17 September, 1913, Page: 7

[10]Irish Independent, 18 September, 1913, Page: 7

[11]Irish Independent, 18 September, 1913, Page: 7

[12]Irish Independent, 18 September, 1913, Page: 5

[13]Irish Independent, 18 September, 1913, Page: 5

[14] Irish Independent, 18 September, 1913, Page: 7

[15] “Shot Down like a Dog – The Finglas Riot of 1913”, Christopher Lee, 2013, https://www.theirishstory.com/2013/04/23/shot-down-like-a-dog-the-finglas-riot-of-1913/#.UdJdHDtxTmQ

[16] Freeman’s Journal, 19 September, 1913, Page: 7

[17] Freeman’s Journal, 18 September 1913, Page:8

[18] Irish Independent, 22 September 1913, Page: 5

[19] Irish Independent, 22 September 1913, Page: 5

[20] Irish Times, 27 September, 1913, Page: 3

[21] Freeman’s Journal, 23 September, 1913, Page: 10

[22]Freeman’s Journal, 1 October, 1913, Page: 8

[23]Freeman’s Journal, 1 October, 1913, Page: 8

[24]Freeman’s Journal, 1 October, 1913, Page: 8

[25] Irish Independent, 8 October 1913, Page:5

[26] Irish Independent, 25 September 1913, Page:7

[27] Irish Independent, 29 September, 1913, Page: 7

[28]Freeman’s Journal, 13 October, 1913, Page: 5

[29] Irish Times, 2 October, 1913, Page: 5

[30] Irish Times, 2 October, 1913, Page: 5

[31] Irish Times, 2 October, 1913, Page: 5

[32] Freeman’s Journal, 19 September, 1913, Page: 7

[33] Freeman’s Journal, 19 September, 1913, Page: 7

[34]Irish Independent, 10 October, 1913, Page: 8

[35] Irish Independent, 10 October, 1913, Page: 8

[36]Irish Independent, 10 October, 1913, Page: 8

[37]Irish Independent, 10 October, 1913, Page: 8

[38]Irish Independent, 10 October, 1913, Page: 8

[39] Irish Independent, 17 October, 1913, Page: 9

[40] Irish Independent, 17 October, 1913, Page: 9

[41] Irish Independent, 17 October, 1913, Page: 9

[42]Irish Independent, 10 October, 1913, Page: 5

[43]Irish Independent, 10 October, 1913, Page: 8

[44]Irish Independent, 10 October, 1913, Page: 8

[45] Freeman’s Journal, 10 October, 1913, Page: 8

[46]Freeman’s Journal, 10 October, 1913, Page: 8

[47]Freeman’s Journal, 10 October, 1913, Page: 8

[48] Freeman’s Journal, 10 October, 1913, Page: 8

[49]Freeman’s Journal, 17 October, 1913, Page: 4

[50] Irish Independent, 24 October, 1913, Page: 6

[51]Freeman’s Journal, 13 October, 1913, Page: 5

[52] Freeman’s Journal, 15 November, 1913, Page: 9

[53] Irish Independent, 16 February, 1914, Page: 6

[54] Irish Independent, 22 June, 1914, Page: 6

[55] Irish Independent, 3 November 1913, Page:5

[56] Irish Independent, 8 December, 1913, Page: 5

[57]Irish Independent, 1 October 1913, Page:5

[58] Irish Independent, 4 November, 1913, Page: 5

[59] Irish Independent, 4 November, 1913, Page: 5

[60] Irish Independent, 18 August, 1913, Page: 6

[61] Sunday Independent, 1 February, 1914, Page: 7

[62] Irish Independent, 4 November, 1913, Page: 4

[63] Irish Independent, 4 November, 1913, Page: 4