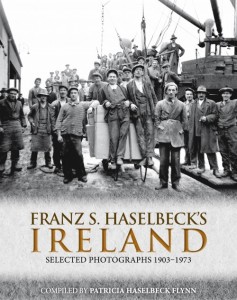

Book Review: ‘Franz S. Haselbeck’s Ireland – Selected Photographs’

Compiled by: Patricia Haselbeck Flynn

Compiled by: Patricia Haselbeck Flynn

Publisher: The Collins Press, 2013

Price: €24.99

Reviewer: Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc

There can be little doubt about it, Franz S. Haselbeck must have been a very, very, interesting man. The son of German Protestant immigrants, Haselbeck was born in Manchester in 1885 and moved to Limerick in the early 1900s, where his parents founded a successful butchery business that was to last 100 years. However Franz Haselbeck developed an interest in the relatively new art of photography which ensured that he would not follow his father into the meat business. He graduated from the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art before working as apprentice to a number of photographers throughout Ireland.

The son of German Protestant immigrants, Haselbeck was born in Manchester in 1885 and moved to Limerick in the early 1900s, before graduating from the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art. He took pictures of Irish life for over 30 years

In 1912 when the Home Rule crisis Ireland set Ireland teetering on the brink of civil war, Haselbeck was back in his home city of Limerick working as a freelance photographer. In this role he met and photographed some of the important political figures of the era, including the veteran Fenian John Daly, the executed 1916 leader Ned Daly’s family, Roger Casement’s companion Rodger Montieth, George Clancy – the Mayor of Limerick assassinated by the RIC – and the controversial Catholic prelate Archbishop Mannix.

He also met and photographed the rank and file of the British Army, Irish veterans of the First World War, the last Constables of the RIC and the republican radicals of both the Irish Volunteer movement and the IRA. (Interestingly Franz Haselbeck’s son joined the RAF, and his own brother was an IRA Volunteer in Limerick…and wasn’t the only German-Protestant IRA Volunteer in the county… ach sinn scéal éile!)

Among his subjects were both British and Irish actors from the War of Independence and the workers at the Ardnacrusha hydroelectric scheme in the late 1920s

The emergence of the Irish Free State in 1922 also saw the introduction of new technologies as the Irish government sought to improve its people’s lot and show to the world what a progressive state independent Ireland could be. When Siemens began work on the Ardnacrusha power station in 1925 Haselbeck was employed as a German / English translator and Assistant Storekeeper. This allowed him to compile a unique photographic record of the ‘Shannon Scheme’ its works and workers – the men who literally “electrified Ireland”.

When the project was completed Franz applied for, but failed to secure, a job with the ESB. Hasselbeck was so bitterly disappointed with this outcome that for the rest of his life he refused to have electricity installed in his living quarters and worked by the light of paraffin lamps! Hasselbeck instead continued his work as a photographer and regularly toured Munster on bicycle photographing public events dressed in his trademark tweed jacket, bow tie and beret.

A lot of people will be familiar with Fr. Browne’s photography, the Cashman Collection and Morrison’s collection of Civil War photos – Haselbeck’s photographic work is of equal importance and was overlooked for far too long. Thankfully the publication of a selection of almost two hundred of his photographs in the book “Franz S. Haselbeck’s Ireland” looks set to rectify this. The book features an amazing collection of images recording several decades of working, social, political, religious and sporting life in Ireland.

Amongst the most fascinating are the posed portraits of RIC Constables at the turn of the last century. Whilst these photos on their own would serve as an invaluable record of the final years of the force, what is even more interesting are the personal stories of those pictured which the author (Hasselbeck’s granddaughter), has gone to the trouble of identifying and tracing their subsequent careers pointing out which of those photographed died in the ‘Great Flu Epidemic’ of 1918, which killed in the War of Independence or survived and those who went on to join the RUC. The book also includes a large number of photographs charting the Irish Volunteer movement, political protests and the War of Independence.

The publication does not just focus on the political. Hasselbeck’s studio portraits of people of all walks of life priests, merchants, artists, schoolchildren, actors, newlyweds -young and old, rich and poor are given equal prominence in the book. Amongst the most striking images is one of the dramatic aftermath of a car crash at Wolfe Tone St., Limerick in 1934. Equally impressive are the portrait of a group of farm labourers at a threshing in Kerry circa 1910 and the Limerick dockers captured on film in 1925.

The only caveat about this excellent collection oh photos is that in some cases the captions can be a bit short.

The only caveat I would express about the work is that in some cases the captions can be a bit short. Having recently produced a photographic history book myself, I know there is always a battle between the author and the publisher about the length of the captions – but in this case the superb quality of the photographs deserved, in many cases, a more elaborate commentary.

To conclude; the photographs of the Haselbeck Collection are of immense historic value. The Collins Press deserve credit for bringing such an important, and long forgotten, body of work to public attention. Furthermore the Irish public owe a great debt to the Haselbeck family for preserving the collection in the forty years since Franz’s death – in particular we are indebted to Franz’s granddaughter Patricia Haselbeck Flynn who not only wrote the book, but who has been custodian of the Hasselbeck Collection for almost twenty years during which time she rescued the photos from a flood, and not one but two house fires.

Franz, an amazing man – an amazing story – amazing photographs!