Ireland and South African Politics – A Tangled History

On the day after the death of the iconic South African leader Nelson Mandela, John Dorney has a quick look at how Irish and South African politics have intersected in the last 100 years.

At the time of writing (December 6, 2013), tributes are pouring in from throughout the world to Nelson Mandela, the long-time ANC leader and first South African President elected by universal, non-racial suffrage. Ireland has been no exception, the Taoiseach Enda Kenny for instance released a statement saying, ‘The name Mandela stirred our conscience and our hearts. It became synonymous with the pursuit of dignity and freedom across the globe’.[1]

Mandela, undeniably a brave and charismatic figure, has also become a consensual icon. He is held to embody a series of values – democracy, anti-racism, non-violence and reconciliation that are held to underpin modern liberal democracies. Mandela was not always such an undisputed figure of adoration in the west however. He was denounced during his long imprisonment for direction of the bombing campaign of Umkhonto we Sizwe (The Spear of the Nation or MK) in the early 1960s as a ‘terrorist’ and a ‘communist’ by among others, Margaret Thatcher. And while in Ireland today it would seem as if everyone opposed Apartheid during its existence, it was not always so.

Afrikaners and Irish Republicans

In the late 19th century Ireland’s first contacts with South Africa were made when Britain took over the formerly Dutch outpost at Cape Town. For the next 70 or 80 years, the Irish presence in South Africa was mainly in the form of troops in the British Army and the odd colonial official.

The British in South Africa inherited a long settled European population as well as an indigenous Africa one. The white population that was first established in Cape Province in 1652, was mainly of Dutch descent but also included a sprinkling of Germans, French Huguenots and Portuguese and spoke a dialect of Dutch known today as Afrikaans. At the time this group were referred to as ‘Dutch’ by the British and often simply called themselves ‘Boers’ or ‘farmers’. Today they prefer the term ‘Afrikaners’.

In the 1830s, especially after the British banned slavery, the Afrikaner population of the Cape grew restive. They had long enslaved the native population to work on their farms and maintained, being devout Calvinists, that the Bible gave them sanction to do so. For this and other reasons, several convoys of Afrikaner, or Boer settlers set off into the interior of South Africa to be free from British rule. The relatively small but heavily armed settler convoys managed to defeat much greater numbers of Zulu, Ndebele and other African warriors to carve out mini-republics in Natal, Transvaal and Orange River areas.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Irish republicans identified passionately with the Boer Republics struggle against Britain. They had little to say about racial oppression of native Africans.

While the British caught up with them in Natal in 1843 and annexed the province, two Afrikaner Republics remained, the Transvaal and the Orange Free State. The British took advantage of internal dissension among the Boers in the Transvaal to annex it in 1877 but were again expelled after a successful uprising and short war in 1881.

Irish nationalists tended to enjoy the spectacle of the British being humiliated by hardy Boer republicans and Irish interest in South Africa was greatly deepened by events of the following 20 years. Gold and diamonds were discovered in the Transvaal, which all but guaranteed that the British Empire would again try to annex the Republic and also meant that some 6,000 Irish settlers came to South Africa to work, mostly in the mining industry. Among them were IRB activists Arthur Griffith (later founder of Sinn Fein) and John MacBride.

When war did break out between Britain and the Boer Republics in 1899, MacBride formed an Irish volunteer unit to enlist in the Boer armies. On the face of it, this was a little contradictory as one of points of contention between the Transvaal Republic in particular and the British was its refusal to grant rights of citizenship to ‘uitlanders’ or European settlers who came to live there. However MacBride seems to have seen the war purely as a way of striking at the British Empire by proxy.

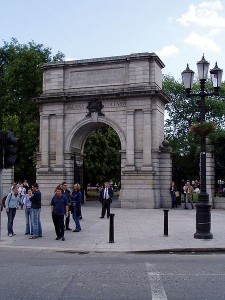

The Irish Brigade, composed of two units together about 300 strong, mostly composed of former miners and engineers, specialised in demolition work but also saw action at a number of major engagements. The Irish fighters suffered about 90 casualties including 31 killed. On the other side as many as 30,000 Irish troops fought in the British forces and suffered heavily, over 4,000 being killed or wounded.[2] Today an arch in Dublin’s Stephen’s Green records the names of hundreds of Dublin men who died in British khaki in South Africa.

The war also saw, principally among Irish unionists, a patriotic mobilisation in favour of the British Empire. In response to a call for volunteers for a new corps named the Imperial Yeomanry, many of the gentry’s sons joined up this new ‘gentleman’s unit’.

For radical nationalists organising protests against the war in South Africa became a major rallying point. James Connolly for instance threw a coffin into the river Liffey in Dublin marked ‘the British Empire’ and riots ensued with British troops. Sean O’Casey wrote, ‘every patriot carries in the lapel of his coat a button picture of [Boer leaders] Kruger, Botha, Steyn, Joubert, De Wet’.[3] In Parliament the Irish Parliamentary Party railed against British conduct in South Africa, especially their treatment of Boer civilians, as many as 20,000 of whom died of disease and poor conditions in concentration camps. Nevertheless the numbers of Irishmen who served in the war was relatively large and while, as in the 1914-18 war, most military service should not be considered a political act, it is clear that Irish opposition to the war was far from universal.

Irishmen fought on both sides of the 1899-1902 Boer War

At this date, the Afrikaners’ complete denial of rights to the indigenous Africans whom they governed did not present a major problem for Irish nationalists. Even many advanced republicans in Ireland made a distinction between self-determination for ‘civilised nations’, such as for instance Ireland, Poland, the Boers and even India and Egypt and the ‘savage races’ of Africa.[4] Griffith argued in his newspaper the United Irishman, not only that white nations such as the Boers had more rights than black Africans but that the war in South Africa could also be blamed on the Jews.[5] John MacBride returned to Ireland but fell out of nationalist activism. He joined the insurrection of Easter 1916 almost by chance and was executed by the British, as much for his role in South Africa as for anything that he had done in Ireland.

The style of the Boer commandos, in particular the wide-brimmed hat pinned up at one side, with the bandoleer of ammunition draped across the chest was later much copied by Irish paramilitaries in the Volunteers and Citizen Army.

From Smuts to Apartheid

The results of the Boer War of 1899-1902 were complex. Although the British militarily occupied the two Boer Republics after about a year of fighting; to suppress the Boer fighters, once they had dispersed in guerrilla formations, proved to be a painstaking and bloody task.

As a result at the war’s end the terms offered by the British were rather lenient. The Boers were returned self-government, inside the new the union of South Africa, within a number of years. Moreover as the Afrikaners had always insisted, political rights were not extended to the Africa majority, contrary to what the British had promised before the war.

In some respects therefore, black Africans were the real losers of a war in which they had had no active part in starting or any control over the outcome.

In the new South Africa their place was to be simply cheap labour for European-owned industries. Many Africans at this date lived a traditional subsistence lifestyle outside of the money economy but they were effectively forced to become wage-labourers by the imposition of a poll tax, or tax on each household in 1905. Some 3-4,000 Zulus were killed, some 7,000 imprisoned and 4,000 flogged in 1906 in a rebellion against the tax. By 1909 some 80% of the men in that region had been forced to become migrant labourers, mainly in the mines.[6]

None of this seems to have greatly exercised Irish nationalists. The internal politics of South Africa had always been principally a way of fighting Irish conflicts by other means. In South Africa itself, some former Boer fighters such as Jan Smuts became dedicated servants of the British Empire. Others such as guerrilla leader Christian De Wet rejected compromise (in a manner in some ways reminiscent of the reaction of some Irish republicans to the Treaty of 1921) and launched an abortive rebellion against British rule in 1914.

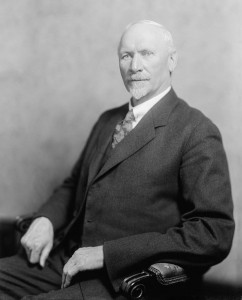

South African statesman Jan Smuts helped to broker a truce to end the Irish War of Independence in 1921. His government in South Africa, while not as rigid as Apartheid, discriminated against Africans on racial grounds.

Irish nationalists, even radical separatists do not seem to have had much to say about De Wet’s rebellion, but many including Irish Parliamentary Party leader John Redmond, in 1916 contrasted the mild treatment of the Boer insurrectionists of 1914 with that of the Irish rebels of 1916. In South Africa most of De Wet’s followers were allowed to go home after a fine or short imprisonment, whereas after the Dublin uprising, 14 men were shot within weeks of surrendering (and two more later hanged) and over 1,000 sentenced to long prison terms with hard labour.

One of the men who was responsible for the suppression of the 1914 rebellion was Jan Smuts and he would go on to play a significant role in Irish history also. Smuts, having fought against the British Army in 1899-1902, later became a general in it and later a statesman and South African Prime Minister. In 1920-21 he came to Ireland and helped, through extensive correspondence with Eamon De Valera, to broker the truce between the IRA and British forces that ended the Irish War of Independence in July 1921. Smuts, though a British general, appears to have been sympathetic to the self-determination and unity of Ireland.[7]

Relations between South Africa and the Irish Free State in the 1920s and 30s were cordial as both were dominions of the British Commonwealth who sought greater autonomy from Britain. Under Smuts’ long premiership in South Africa, racial segregation was a reality and Africans and Europeans had unequal rights. However there was a limited black and so called ‘coloured’ franchise, subject to property and education restrictions, (though not after 1936 a right to run for office) and residential segregation was not systematically enforced.

This all changed in 1948 when the National Party, which represented hard-line Afrikaner views defeated Smuts’ United Party and over the next decade introduced a series of racial laws we now know by the Afrikaans euphemism ‘Apartheid’ (roughly ‘separateness’). The population was now officially classified on a racial basis into whites, blacks and ‘coloureds’ and marriages and any sexual relation between the races were made illegal. Racially mixed residential areas were declared illegal and the non-white population was typically expelled into ‘townships’ and their homes demolished. Black South Africans now needed special passes to travel into white-designated zones. Education and amenities were also segregated and in 1959 the few black South Africans with the right to vote lost their franchise.

Apartheid, in short, institutionalised white, and in particular Afrikaner nationalist, domination in South Africa. Initially this does not seem to have been greeted with a great deal of anger in Ireland.

Irish Reactions to Apartheid

There was not a great deal of protest in Ireland to the introduction of apartheid. In 1952 South African High Commissioner in London, Dr A. L. Geyer, visited Dublin and was a guest of Taoiseach Éamon de Valera.

A significant number of Irish people took up offers by the South African government for white settlement in the post 1948 period, with roughly 2,300 people making the journey. By the 1960s, due to an accumulation of settlement since the late 19th century roughly 60,000 people either born in Ireland or of Irish descent lived in South Africa. [8]

The turning point in Irish perceptions of Apartheid South Africa was the Sharpeville massacre of 1960. The African National Congress, protesting about the laws of racial segregation and in particular the pass laws, carried out a campaign of non-violent resistance. However in 1960, one such demonstration was fired on police in at Sharpeville, near Johannesburg, killing 69 peaceful demonstrators. The massacre was beamed around the world on television effectively starting the worldwide anti-apartheid movement.

It also convinced Nelson Mandela and other ANC leaders that non-violent tactics would not work against the apartheid regime and saw them embark on a bombing campaign, limited initially to destruction of infrastructure, rather than human targets, for which he and other leaders were in 1963 sentenced to a lifetime in prison.

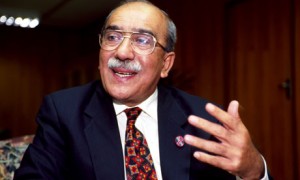

The Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement (IAAM) was founded by an ANC exile and barrister, Kader Asmal, who arrived in Ireland in 1966. Asmal later served as Minister of Water and Electricity in South Africa in the 1990s. The IAAM mounted such campaigns as boycotts of South African fruit produce and protests at the visit of the South African Rugby team to Ireland in 1970, all calculated to increase the international isolation of South Africa.

Perhaps the most extraordinary grassroots manifestation of anti-Apartheid activism in Ireland was the strike by Dunne’s Stores shop workers in 1984, who refused to handle South African goods in solidarity with the victims of Apartheid in South Africa. Ten women workers led by Mary Manning and Karen Gearon were sacked for upholding their union (IDATU)’s ban on handling South African goods and remained on strike for over two years thereafter. Their cause was taken up by, among others, Catholic Bishop Eamon Casey and South African activist and Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

By the 1960s, Irish public opinion was against Apartheid. One of the most striking examples was a group of women workers in Dunnes Stores

The Irish Republican movement’s attitude by the 1970s had shifted completely from the early 20th century affinity with the Boer cause to a recognition of the ANC as a fellow ‘liberation movement’. Nor did this remain purely at a theoretical level. The ANC’s armed wing MK had noted the Provisional IRA’s proficiency with explosives and sought training from them in the late 1970s. According to Kader Asmal, contact was made with the IRA via Micheal O’Riordain, the head of the Communist Party of Ireland and through him Gerry Adams, to train two MK members in explosives in Dublin for two weeks. In 1980, Asmal arranged, through the same contacts, two IRA members to travel to South Africa to reconnoitre and plan the bombing of Sasol, South Arica’s major oil refinery, an attack Asmal described as a great propaganda success even if the physical damage to the plant was superficial.[9]

The South African movement’s links with militant Irish republicans were a sore point for some other anti-apartheid campaigners, however. Fine Gael politician and Taoiseach Garret Fitzgerald resigned from the IAAM as it did not prohibit Sinn Fein members from joining. In 1990, Nelson Mandela visited Ireland to thank anti-apartheid campaigners for their work and called on the British government to negotiate with the IRA, an act which was widely criticised at the time. During the Northern Ireland peace process of the late 1990s one of the key international intermediaries was senior ANC member Cyril Ramaphosa.

Conclusions

Human history weaves a tangled path. Inevitably those comparing their countries with others far away see parallels which confirm what they want to believe and what suits their arguments in their domestic politics. Irish republicans at the start of the 20th century had little to say, by and large, about the oppression of black South Africans, identifying instead with the most racist European faction, the Afrikaner republicans.

By contrast at the end of that century the Irish Republicans of that era identified totally with the anti-apartheid struggle. One of the things this illustrates is the discrediting of racialist ideology in the western world since the late 20th century, an ideology which was so dominant at the start of the century that even anti-imperial nationalists were not totally free from it.

Late 20th century Irish republicans identified with the ANC as a fellow ‘Liberation movement’ and even gave explosives training and sent members to help their armed wing, MK.

Curiously enough, whereas Irish unionists in 1900 identified with the British Empire and its conquest of South Africa, in the 1980s some loyalists forged links with hard right Afrikaner groups in South Africa and a paramilitary group named Ulster Resistance (subscribed to by, among others, current DUP leader Peter Robinson) imported substantial quantities of South African arms in the late 1980s.[10] Later on during the Parades controversy of the 1990s when the Orange Order tried to enforce its right to march where it pleased, it sometimes claimed rather unconvincingly it was fighting against a kind of ‘apartheid for Protestants’.

Finally, some in Ireland will argue that Nelson Mandela and the ANC’s armed struggle represents a good moral example of a liberation movement, as opposed to the illegitimate and immoral armed campaign of Irish republicans since the 1970s. Care should be taken here. It is clear that black South Africans faced much worse oppression than Northern Ireland Catholics prior to 1969. However it is also true that the two armed movements did see each other in fraternal light.

It has also been argued that the Provisional IRA’s campaign was much bloodier and more indiscriminate than MK’s bombing campaign, which set out to damage property rather than kill people. However while the death toll of the bombing operations was low, the body count was much higher in the townships of South Africa as the ANC fought not only with the state security forces but also with rival African groups such as the Zulu Inkatha (which appears to have been backed by state forces), in violence in which some 14,000 people were killed.

The South African Truth Commission found that both there and in border guerrilla camps, ANC and MK units routinely practiced torture and summary execution of suspected spies and political enemies.[11] The point here is not to equate the two movements but simply to point out that the truth is rather more complex than the moral ANC struggle on one side versus the illegitimate terrorism of the PIRA on the other. All political violence involves degrees of immorality, however justified the cause.

Today the era of liberation in South Africa is over. Political equality was achieved in 1994 but the vast disparities both in wealth and in opportunity between rich and poor and to great degree between black and white remain. In 2012 police fired on striking mine workers at Marikana, killing nearly 40, a clear indication that issues of basic rights and of state violence remain unresolved even in majority-ruled South Africa. Parallels with Ireland no longer seem obvious to political activists.

References

[1] Irish Independent 5 December 2013 http://www.independent.ie/irish-news/tributes-paid-worldwide-to-a-great-light-nelson-mandela-29814136.html

[2] History Ireland, MacBride’s Brigade in the Anglo-Boer War http://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/macbrides-brigade-in-the-anglo-boer-war/

[3] Donal P. McKracken, Forgotten Protest, Ireland and the Anglo Boer War p72

[4] Irish Freedom (IRB newspaper) December 1910 for instance.

[5] Marilyn Reizbaum, James Joyce’s Judaic Other, p38 see here

[6] The Bambatha Rebellion, Alastiar Boddy Evans, online here.

[7] An instance of Smut’s correspondence with De Valera is online here.

[8] History Ireland, The Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement. http://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/an-boks-amach-the-irish-anti-apartheid-movement/

[9] Irish Times, August 29, 2011 http://www.irishtimes.com/news/ira-aided-anti-apartheid-bombing-claimed-asmal-1.609314

[10] http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2507&dat=19890424&id=hTNAAAAAIBAJ&sjid=RFkMAAAAIBAJ&pg=3992,2275287