Transport in 19th Century Dublin

Michael Barry looks at how people got around in 19th century Dublin

Georgian Dublin was an intimate city, easily contained within its two canals, and it was possible to walk between the main points of the capital. Up to the end of the eighteenth century, transport in Dublin was primitive. By the end of the 19th century, however, all that had changed. The city was criss-crossed with electric tramlines and railways took the well to do out do distant suburbs. In short the 1800s, often considered a period of decline for Dublin also saw much of the Irish capitals’s infrastructure improve dramatically.

Of canals and omnibuses

The carts and coaches in use in 18th century Dublin were slow and costly. For Dublin a radical change was the canals that were being built around that time, which improved connections to the rest of the country.

Work commenced on the Grand Canal scheme in 1757. The last section, the Circular line from James’s Street harbour to Ringsend, was completed in 1796. The more northerly Royal Canal route to the Liffey was opened in 1801. Carrying passengers and freight, the canals linked Dublin to the midlands and to the rivers Shannon and Barrow. However, travelling by canal was slow. It took over 13 hours to travel from Dublin to Athy.

Competition in transport has always been a healthy force. In May 1834, in an effort to compete with coach services, fast ‘fly boat’ services were established on the Grand Canal. Two horses towed these boats at speeds that averaged six to eight miles per hour. This service lasted only until 1852, as passenger services on the canals were not able to compete with the railways that were being built.

The first attempts to move people rapidly around and out of Dublin were the canals and horse drawn cars.

Horsepower had been the principal means for connecting Dublin to the rest of the country. Mail-coach services had been established by 1789.

Charles Bianconi, based in Clonmel, began a passenger-coach service in 1815. In the decades that followed, Bianconi and other operators provided regular coach connections across the country, many operating out of Dublin. Horse transport grew in line with the city’s expansion and private carriages and public hackneys carried people to and fro. As the nineteenth century proceeded, the city grew larger and developed significantly in a southerly direction. The poor and the lower middle class could not easily afford a cab or carriage. They had to live within walking distance of their employment.

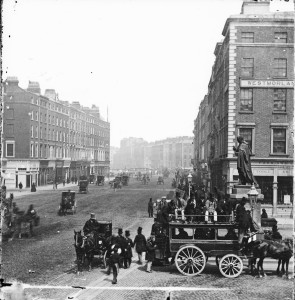

Distances increased as the city expanded, and by the mid-century, horse omnibus services were set up. These involved large horse-drawn coaches operating on a predetermined route, running at fixed times. These double-deck vehicles were pulled by two or more horses. Clondalkin, Rathmines, Terenure, Clontarf, Rathfarnham and Sandymount were among the areas served. Fares were low, and patronage grew accordingly. The omnibus service and the subsequent trams liberated the lower middle class, who could now choose to live at a much further distance from their employment.

The first trams

Rattling along on the iron wheels of an omnibus was not a comfortable way to travel, certainly not on cobblestones or unpaved roads such as those of the new (and parsimonious) Rathmines Township. Indeed, it was the poor state of the streets of the developing cities of the United States that led to the development of horse trams there from 1832 (in New York, by an Irishman, John Stephenson). Despite the appeal of the smooth ride of steel wheel on rail, there was a lag in the development of trams in Europe.

The new technology was introduced to Dublin by an American entrepreneur, George F. Train, who, in 1867, laid a demonstration section of rails along Aston Quay. The Corporation decided these were a nuisance and ordered their removal. It was to take until February 1872 before the first Dublin horse tram ran. This operated between College Green and Garville Avenue in Rathgar. These trams, pulled by two horses, were double-deck with the driver and the passengers on the top deck and open to the elements. Trams were initially laid mainly to the southern suburbs of the city and catered for a mainly middle-class clientele. As the tramways were private undertakings, this made eminent sense for extracting substantial fares from the passengers.

Rattling along on the iron wheels of an omnibus was not a comfortable way to travel, certainly not on cobblestones or unpaved roads. Horse drawn trams gave a much smoother ride

In a letter to the Freeman’s Journal in March 1878, Maurice Brooks MP criticised the Dublin Tramway Company’s elitist approach, while noting that it was ‘making excellent returns to the proprietors and proving of great convenience to passengers of the genteel and well-to-do classes.’

In time, the tram network did move from the lucrative southern routes towards the north side and the trams ran along North Circular Road, Parkgate Street and through Drumcondra and Clontarf. The tramway proved to be a spur to development in such areas as Clontarf, which had lagged behind the townships to the south.

The line that opened there in 1873 fostered expansion in that area. New houses were built within walking distance of the tramway service. Dublin trams proved popular. 137 tramcars ran on 32 route miles of track by 1881 when three companies amalgamated to form the Dublin United Tramways Company (DUTC). On the eve of electrification a typical fare on the horse tram was threepence from Nelson’s Pillar to Clonskeagh. This service ran from 8.00 a.m. to just after 10.00 p.m.

Electric trams replaced horsedrawn trams in Dublin after the 1890s

The world’s first electric tramway had been developed by Werner von Siemens in Berlin in 1881. This technology spread to the United States and, by July 1890, one sixth of the tramways there were electrified. It was more economical than the heavy cost of maintaining fleets of horses (the DUTC operated a ratio of around ten horses per tram car), not to mind the problem of dispersal of horse manure. Electric trams were faster: with the same number of cars, a greater frequency and greater overall carrying capacity could be obtained. DUTC officials visited locations in Europe to inspect electric tramways. Another delegation, which included the DUTC Chairman William Martin Murphy, visited the United States during the early 1890s.

There was opposition to electrification. The Dublin Carmen’s Union, representing the jarveys, objected as they feared that the electric trams, unlike the horse trams, would be significantly faster than their vehicles. The Lord Mayor protested, pointing out the loss in growing oats and horse breeding to farmers.

The first electric tram was operated from Haddington Road to Dalkey in May 1896 by the Dublin Southern District Tramways Company (DSDT). The 500-volt DC supply was provided by a generating station at Shelbourne Road. The service proved popular and the coastal railway line lost passengers. In a bid to regain patronage the Dublin, Wicklow & Wexford Railway Company opened new stations at Merrion and Sandymount and reduced fares.

The DSDT amalgamated with the DUTC in September 1896. Over the next few years, electrification of Dublin’s tramways gathered pace and the end of the horse cars was announced in January 1901 when the Sandymount tram line (via the difficult low bridge at Bath Avenue) was finally electrified.

Suburban railways

The first railway in Dublin opened just before the dawn of the Victorian age. The Dublin to Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire) railway was the first suburban railway in the world. Originally a canal had been planned to provide a connection from Dublin to the newly-constructed Kingstown harbour. The silting up of Dublin port meant that larger vessels could not use it, and called at Kingstown instead.

As Kingstown grew in importance, the question of a connection with Dublin was discussed. The age of great enthusiasm for railways had begun and, in 1825, a petition was made to the House of Commons proposing a railway.

The Dublin and Kingstown Railway Act received Royal assent in September 1831. The first committee meeting was held in November 1831. The professional men and merchant princes of Dublin were represented by names such as Barton, Pim, Ferrier and Roe. Wexford-born Charles Blacker Vignoles, experienced in construction of railways in England, had been appointed as Chief Engineer.

Dublin’s first railway line, from the city to the coastal suburb of Kingstown (now Dun Laoighaire)opened in 1837

William Dargan’s tender for constructing the line was accepted. Dargan was to become known as the ‘Father of Ireland’s Railways’, building these across the country in the great expansion that followed. Dargan’s legacy of the line to Kingstown – the solid stone bridges, the railway formation and the parabolic sea wall along by the coast – can still be seen today, from the rear of Pearse Station to the termination of the initial line near the West Pier at Dún Laoghaire.

The line, to a 4 ft 8½ in gauge (the distance between the running edges of the rails), opened in December 1834. It was planned to continue the line to the south. A new wharf to cater for steamers, including the mail boat, was built to the south of the harbour. The extension to the site of the present Dún Laoghaire station was complete by May 1837, again constructed by Dargan.

The Dublin & Kingstown Railway (D&KR) now began to make arrangements for an extension to the growing township of Dalkey. An innovative scheme was prepared to lay an atmospheric railway there from Kingstown. It followed the route of the quarry tramway recently used during construction of the new harbour. Objections were made to the proposed route but a cutting was eventually built with a series of ‘flower bed’ bridges to camouflage this.

With no locomotive smoke-stack to be coped with, the initial clearance of bridges over the cutting was low. These can be still seen today on the Dún Laoghaire seafront near the Royal Marine Hotel. A cast-iron pipe with a leather flap valve was laid between the rails along the course of the line.

A steam engine located in a power house at Dalkey created a vacuum in the pipe. A small carriage was attached to a piston in the pipe. At Kingstown, the brakes would be released and the vacuum would pull the carriage, complete with passengers, up the incline to Dalkey. The return journey was made by gravity. This, the first commercial use of an atmospheric railway to carry passengers, opened in 1844. Advanced technology can be a difficult task.

Many problems were experienced with the ox-hide flaps on the atmospheric pipe. Cast-iron plates were laid on the flaps and tallow employed to achieve a seal. However, the vacuum was difficult to maintain. There were frequent failures with the valve. Passenger traffic also dropped off, particularly during the Famine years. The atmospheric line lasted until April 1854. A deeper cutting was excavated for steam traction and a track using the new Irish gauge of 5 ft 3 in installed.

Meanwhile, the great national railway expansion was underway. Throughout the nineteenth century, Belfast raced ahead of Dublin in terms of industrial growth and expansion. And so, in the late 1830s, the next railway was not from Dublin, but from Belfast. Construction of a line out of Belfast began in 1837 and the section to Portadown opened in 1842, operating to a 6 ft 2 in gauge. The concept of a Dublin to Belfast railway had been in vogue since 1825. The Dublin & Drogheda Railway (D&DR) was planned to be part of this route. Disagreements over whether it was to be inland or coastal delayed the building of this line.

Work started in 1838 on a short portion from the Royal Canal in Dublin to Portmarnock, directed by the company’s engineer, John Macneill. Based on Macneill’s advice, the company came to favour a 5 ft 2 in gauge. With the prospect of different gauges, alarm bells began to ring. The Inspector General of Railways, Major-General Pasley, was asked to investigate.

He consulted widely and investigated the variety of gauges that had emerged in Britain, which included 5 ft and 5 ft 6 in. After due consultation, he recommended a mean of 5 ft 3 in, which is still the standard gauge throughout Ireland. This gauge is also still in use in parts of the Australian and Brazilian railway networks.

Construction continued on the D&DR using the revised gauge and, in March 1844, a train carried the Lord Lieutenant and over 500 passengers from the Royal Canal to Drogheda. Two months later, the same Lord laid the foundation stone for the new terminus at Amiens Street. He followed this ceremony by knighting Macneill. It was to take until 1855 before there was a permanent rail connection from Dublin to Belfast. The reason for the delay was the difficult crossing of the river Boyne. Based on an original concept by Macneill, a great bridge was built across the Boyne valley at Drogheda. The river spans used wrought-iron lattice girders. This was the new material of the time and the railways used the products of the Industrial Revolution with enthusiasm.

The D&DR opened a branch line to Howth in 1847, with the hope of generating cross-channel traffic out of the harbour. This never materialised. However, there was commuter traffic and this helped the growth of residential Howth. The D&DR actively promoted development in Howth and other areas near its northern line, such as Balbriggan and Malahide. In 1861, there was on offer a free first-class ticket, valid for fifteen years, for each house over a £50 valuation. In those class-conscious times, a house under that valuation would only merit a second-class ticket.

Throughout the nineteenth century, Belfast raced ahead of Dublin in terms of industrial growth and expansion and in railway construction.

William Deane Butler designed the terminus at Amiens Street (now known as Connolly Station). This grey granite building, albeit a little stolid, has an imposing central Italianate tower. By 1876, the Great Northern Railway (Ireland) was formed, and incorporated most railways to the north of the country. The GNR(I) built its red-brick headquarters at Amiens Street, to a design by John Lanyon and was completed in 1879. It matches the nearby Deane Butler station building with another Italianate tower. On the north side, there is a fine and elaborate example of polychromism. This particular use of patterns of red and yellow brick became a characteristic of GNR(I) station architecture.

The Great Southern & Western Railway (GS&WR) was the line to the south-west. Construction of the line began in 1845. Two eminent men of the Irish railway age were involved. Sir John Macneill was appointed as company engineer. William Dargan’s construction company was one of the principal contractors. In August 1846 a service was opened to Carlow, having branched off from what is now known as the ‘mainline’ at Cherryville.

Progress was rapid. Thurles was reached in 1848. By October 1849 Cork had a railway service using a temporary terminus located to the north of the city. The GS&WR headquarters and station at Kingsbridge (now Heuston Station) proclaims a date of 1844 but the architect for the building was selected by competition only in 1845. The building was completed in 1848.

The station is imposing and dominates its location by the Liffey. The design, by the English architect Sancton Wood, employs decorative carvings and Corinthian pillars and balustrades. There is a hint of India about the cupolas on either side of the building. Such eastern exoticism was not unknown in the Dublin of these years. In the adjacent bridge at Kingsbridge, an Egyptian theme was applied to the abutments, and was also used at Broadstone Station.

The front of the Kingsbridge Station accommodated the company administrative offices. Córas Iompair Éireann (CIÉ, the Irish transport company) Board meetings are now held in what was the GS&WR boardroom. The operational part of the station is at the rear. The platforms are covered by a large roof supported by cast-iron columns. This, one of the largest examples of early railway roof-spans, was designed by Macneill. Dargan was the contractor and the ironwork was supplied by J. & R. Mallet of Dublin.

In the early 1840s a railway from Dublin to the west, to serve Athlone, with a branch to Longford, was proposed. An Act was passed in 1845 that enabled the Midland Great Western Railway (MGWR) to begin construction. The Act also authorised the company to purchase the Royal Canal. The first part of the MGWR was to be built at the side of the Royal Canal, following it closely for nearly 60 kilometres out of Dublin. Services to Kinnegad began in 1847 and to Mullingar in 1848. By 1847, the company had been authorised to extend to Galway and services to there began in 1851.

John Skipton Mulvany was engaged to design many of the company’s stations. His outstanding monument in Dublin is the station at Broadstone. The building was completed in 1850, with the eastern colonnade being added in 1861. This striking building dominates the plateau of open space where once the Royal Canal harbour lay. The frontage has vestiges of an Egyptian theme. At the western side of the station were the departure platforms; on the eastern side the long neo-classical colonnade.

The finest Victorian railway station in Dublin, Broadstone, later fell into disuse and is now the headquarters of the national bus company

The station provided a graceful welcoming sight of Victorian Dublin for travellers from the west. None can better Maurice Craig’s description of the building in his Dublin 1660-1860: ‘The Broadstone … is the last building in Dublin to partake of the sublime. Its lonely grandeur is emphasised now by its disuse as a terminus … It stands on rising ground, and the traveller who sees it for the first time, so unexpected in its massive amplitude, feels a little as he might if he were to stumble unawares upon the monstrous silences of Karnak or Luxor.’

It is sad that the station, probably the city’s pre-eminent Victorian building, is located in a backwater largely out of public view. In addition to its architectural splendour, the location is a poignant testimony to Dublin’s transport connections, past and present. It was a terminus for both the canal and the railway. Last used as a railway station in 1937, it now serves as the headquarters of the national bus company, Bus Éireann. Broadstone’s architect designed many other railway buildings including the original station at Athlone.

A connection south to Wexford with the possibility of cross-channel services spurred consideration of a new railway south of Kingstown. The D&KR tried, but failed, to get an Act passed for a connection to Bray. An inland route was mooted and, in 1851, the Dublin & Wicklow Railway (D&WR) was empowered to build a railway from Dundrum to Bray and also from Dalkey to Bray. Another company, the Dublin & Bray Railway (D&BR), began work on the Dublin to Dundrum section. It was not successful and, in 1853, the D&WR took over the D&BR line. In July 1854, the first train service operated from a temporary station at Harcourt Road to Bray and also from Bray to Dalkey.

The Kingstown to Sandycove atmospheric section had been rebuilt for the passage of steam trains. The great English engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, was involved with the works underway on the line south of Bray. Timber trestle viaducts and tunnels were required along the difficult Bray Head section. By 1855, there were services between Kingstown and Wicklow.

In 1858, a new bridge was constructed by Courtney, Stephens & Bailey to carry the D&WR across the Grand Canal to a new terminus, which was being built at Harcourt Street. The station there, designed by George Wilkinson, opened in 1859. As with Amiens Street and Westland Row stations, the tracks and platforms were built high above road level, as the connecting tracks had to pass over the surrounding streets.

Thus, by 1859, there were five railway termini on the perimeter of the central city. This was an unusually large number and was more suited to Dublin’s former glory as second city of the Empire than the more modest position it was to hold during the Victorian era. Not only were the termini located at some distance from each other, but cooperation was not notable among the different railway companies.

Several connecting schemes were proposed for a direct link from Westland Row to Kingsbridge. None of the schemes saw the light of day. Successful completion of the present plan for the underground urban rail system from the Docklands, running under the Liffey to St. Stephen’s Green and onto Heuston Station, will mark the fulfilment of the grand dream to connect the termini via the River Liffey.

The quickening flow of manufactured goods which were in demand led to pressure for a rail connection with the docks. The Dublin Builder noted in 1861 that ‘160,000 tons of traffic are now carted through Dublin, to the great encumbrance of the streets.’ The advantage of a rail connection with the docks would save the ‘painful transit of boilers, locomotive engines and rolling-stock made in England and dragged by long teams from the Liffey through the streets to their termini.’

IModern Dublin, chronically congested would do well to recreate the easy access that was a characteristic of Dublin at the end of the Victorian era.

The West was linked to the port when the MGWR built a rail connection to the docks in 1864. Like its parent railway, the line followed the Royal Canal all the way to the North Wall. The south of the country was connected to the docks by a GS&WR route, completed in 1877. This line passed over the river Liffey to the north of Kingsbridge, then through a tunnel under the Phoenix Park. It looped around the limits of the developing Victorian city in a great circle, passing through cuttings in Cabra and then joined the MGWR line at Glasnevin.

As the nineteenth century ended, a substantial transport infrastructure was in place in Dublin. A significantly-improved port was connected to the railways, which radiated across Ireland. The railways were soon to reach their apogee, followed by rapid contraction, which occurred during the next century. Within the city itself, citizens enjoyed easy and rapid access to the new suburbs of the late-Victorian city, travelling on electric trams or suburban railways. The rise of the internal combustion engine and the decline of the trams came in the twentieth century and led to gridlock on the city streets by that century’s end.

Into the future

We are just coming out of the 2008 recession. It is very likely that the numbers of cars on Dublin’s roads will increase exponentially over the coming years. Dublin, a European capital city, is in danger of becoming utterly congested. This is not the model for our 21stcentury city, to be enjoyed by all citizens. Neither would such a city in stasis be suitable for continued attraction to multinationals and the employment they bring.

More quality public transport is what is required: to make efficient use of the scarce resource that is road space, as well as to lure motorists from their cars. I suggest the model is there for us to see: to recreate the easy access that was a characteristic of Dublin at the end of the Victorian era. We are fortunate to have two Luas networks (with a further extension being built), but this is limited. I suggest what we need is a dense light rail network around the city, more or less the same as we had over a century ago.

Michael B. Barry is a historian and the author of, among other works, Victorian Dublin Revealed. He has worked as a consultant on transportation projects both in Ireland and around the world. Among his other books are; ‘Across Deep Waters, Bridges of Ireland’; ‘Through the Cities, the Revolution in Light Rail’. and ‘Homage to al-Andalus’.