Never Lukewarm: Séumas Robinson’s War of Independence

Daniel Murray on Seumas Robinson, commander the IRA Third Tipperary Brigade in the War of Independence.

The Third Man

The Third Tipperary Brigade was among the most prominent in the Irish War of Independence. Ernie O’Malley accredited it with having created the fighting spirit of the IRA in the first place, to the point of other units preferring to fight it out to the bitter end if surrounded rather than a prudent withdrawal in order to live up to the martial idea of the Third Tipperary Brigade. Séumas Robinson was one of the three men O’Malley attributed with creating that bold if troublesome tradition, the others being Dan Breen and Seán Treacy.[1]

Unlike Dan Breen and Sean Treacy, whom he outranked in the IRA, Seumas Robinson is not well known today.

All three became legends in their own lifetimes. Breen’s memoir guaranteed his fame to new generations. Judging by its re-prints, it remains in popular demand as well as much-thumbed by historians. Treacy did not survive the War but the memory of his exploits earned him the attention of writers looking for an Achilles to their Homer.

In contrast, Robinson has been treated as the middle child of the three by historians. Worth a few page numbers in an index, maybe, but not much more than that, with little desire to better understand the part that he played.

Robinson’s role in the Third Tipperary Brigade was a difficult one, and one not easily appreciated by onlookers. As Brigade O/C, he was a middle-manager in the IRA: responsible for the behaviour of his subordinates who did not always respect him, while answerable to his superiors who “admired but…did not like him.”[2] It is to explore these complicated, sometimes contradictory, feelings inspired by this complex, driven man that this article aims to do.

First Impressions

The Third Tipperary Brigade was formed in October 1918, with Robinson elected as Brigade O/C, Treacy as Vice Commandant, and Breen as Quartermaster. According to Breen in his memoir, Robinson’s promotion had been decided for him beforehand by himself and Treacy.

A rising star in the Volunteers, Treacy had been asked by Michael Collins to take the post of full-time Volunteer Organiser for Tipperary. However, Treacy was unsure as to whether he could commit to both that and the role of O/C. He was also concerned that neither he nor Breen had the social standing or the finances.

Dan Breen attempted to write Robinson’s central role in Tipperary out of history.

They were about to request that GHQ send them someone more suitable to take over, when they heard of a recent arrival to Tipperary who had been a participant in the Easter Rising, and who was currently working as a farmhand at the house of Eamon O’Dwyer, another organiser for the Tipperary Volunteers.

Upon meeting Robinson at O’Dwyer’s farmhouse, Treacy and Breen decided that he would be sufficient for the part. As Robinson was a newcomer to Tipperaryand dependant on his farmhand work for money, he was a strange choice if social standing and finances were so important.

A few days later, Breen and Treacy met Robinson again at O’Dwyer’s and asked him if he would agree to take the post. Robinson heard them out while busy milking. When he was done with that, instead of staying to talk, Robinson took the milk-pall and left, saying only over his shoulder that he would be prepared to do whatever they asked of him but he had to get back to his job. Robinson was later elected as O/C on Breen’s proposal which Treacy seconded. The man of the hour was absent as Robinson was serving out a sentence in Belfast jail.[3]

Robinson could hardly have been thrilled to read of himself as a bumptious drone who had accepted a figurehead O/C post that he had otherwise been indifferent to. In his Bureau of Military History (BMH) Statement, Breen went further in describing Robinson’s intended part to have been that of a ‘stooge’ or ‘yes-man.’[4]

Stooge?

Breen’s version is supported in part by that of another Brigade member, Thomas Ryan, who also attributed Robinson’s rise to the prestige of his 1916 record and to the behind-the-scenes prompting of Treacy. While Robinson held the title, Ryan was in no doubt that it was Treacy who held the power. While not present at the election, Ryan suspected that it had been Treacy who had suggested Robinson in the first place.[5]

Breen’s version is supported in part by that of another Brigade member, Thomas Ryan, who also attributed Robinson’s rise to the prestige of his 1916 record and to the behind-the-scenes prompting of Treacy. While Robinson held the title, Ryan was in no doubt that it was Treacy who held the power. While not present at the election, Ryan suspected that it had been Treacy who had suggested Robinson in the first place.[5]

This belief is corroborated by someone who did attend the election: Edmond McGrath. According to McGrath, Treacy turned down offers of the command in favour of Robinson, whose praises Treacy sang to all concerned. Other than giving Treacy, not Breen, the leading role in pushing for Robinson, McGrath’s account tallies with Breen’s.

However, Breen did widely exaggerate Robinson’s status as an outsider. Though McGrath did not know Robinson personally at the time of the election, he was already aware of the considerable time Robinson had spent in organising the Volunteers. Michael Davern went as far as attributing the considerable growth of the Brigade to Robinson’s energy. [6]

Treacy’s desire for another man at the O/C helm can be explained by a need to delegate his workload, a task he would not have entrusted to someone he thought incapable of it. By the time of mid-1920, the two had become, in the opinion of Ernie O’Malley, an “ideal combination” (not least in finding ways to tease O’Malley).[7] In underestimating Robinson’s qualifications and experience, Breen was being either catty or woefully uninformed.

Eamon O’Dwyer

Robinson, originally from Belfast, was drafted into Tipperary to help organise the Volunteers there in 1917

A native of Belfast, Robinson had grown up in Glasgow and had joined the branch of the Irish Volunteers there. In 1916, he was told to report to Dublin for the upcoming Easter Rising. Despite its failure and his consequential imprisonment, his participation and the contacts he made in prison were to stand him in good stead in the years to come.

Post-prison, Robinson moved to Tipperary to help organise the Volunteers there. As far as he was concerned, the only place for him now was Ireland. Returning to Belfast, however, did not seem to have been of interest to him. Besides, he had already made a contact in Tipperary through a prison acquaintance: Eamon O’Dwyer.[8]

O’Dwyer was by then a veteran activist in South Tipperary, having been involved in a daisy-chain of nationalist societies such as the IRB, the Irish Volunteers, and the Gaelic League. A quiet, behind-the-scenes player, O’Dwyer was content to work among the grassroots to ensure the continuation of his beloved movement.[9]

This work included talent-spotting Robinson for the Brigade. The two of them had shared many discussions in Reading Jail on what they would do when free. O’Dwyer had aired his dream of creating a community centre for Irish nationalism. Robinson loved the idea, and readily accepted the offer to come and help out.[10]

Robinson arrived at O’Dwyer’s newly acquired house in Kilshenane, County Tipperary, on January 1917, in the midst of a snowstorm.[11] If Robinson was going to be staying in Ireland for the upcoming fight, he might as well go to where he was wanted.

Honesty, Hustle and Zeal

The priority of the Volunteers in the years after the Rising was the acquisition of weapons, largely by robbery.

As part of this, Robinson and O’Dwyer led a break-in at the house of a British army major who lived locally, where they were confronted by an irate major and his female secretary. A firm believer in civilian property rights, Robinson offered to let the secretary show them around the house while searching for weapons to ensure that nothing else was taken.[12]

Robinson earned his keep at Kilshenane House as a farmhand. A city slicker, he made up for his lack of rural know-how with “honesty, hustle and zeal.”[13] It was fortunate that he had these virtues in abundance, for his work often left something to be desired. The resulting ribbing over one disastrous attempt to tackle up a donkey lasted long after Robinson was made Brigade O/C, which he took in good humour.[14]

Robinson also spent time back in prison for his involvement in the Volunteers. These periods of detention at His Majesty’s pleasure may have been inconvenient, but they did give his peers the chance to see his implacable character up close. At Stafford Gaol, he was remembered as a “small, little man of steel with the russet stubble and the shy, retiring manner” who, within days, became known to staff and inmates for his courteous but firm refusal to sign any of the prison paperwork put before him.[15] If some of his colleagues would find him irritating in the years to come, for now it was enough that he annoyed the enemy.

Soloheadbeg

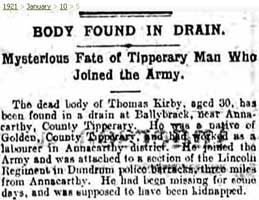

On 21 January, 1919, Robinson, Treacy and Breen were part of a team that ambushed a cart of gelignite on its way to Soloheadbeg quarry. Escorting the cart were two officers of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), and in the resulting confrontation, both were shot dead.

Not everyone in the revolutionary movement was overly impressed with the deed. Breen bitterly recalled the cold-shouldering from otherwise ardent republicans he and the others received in the aftermath.[16] Nonetheless, the ambush has been established as the official start of the War of Independence. Much has been written about the ambush; its importance here is how its two main participants, Breen and Robinson, both took the opportunity in their later accounts to belittle the other.

Soloheadbeg is commonly remembered as the action that began the War of Independence. Breen and Robinson’s accounts of it are highly contradictory.

In Breen’s memoir, the details of the ambush were worked out between him and Treacy, with what Robinson might have thought being unimportant. [17] Breen went further in his BMH Statement in saying that Robinson had not been consulted at all about the ambush plans, and that neither he nor Treacy had told Robinson about their agreed plan to shoot the policemen whatever happened.

This was not because of distrust, but because they did not think it was any of his business to know – an extraordinary thing to say about the Brigade O/C. Robinson did not join the rest of the party in their stakeout of the prepared ambush site until a couple of days before the ambush took place, meaning he could have missed it entirely had the gelignite escort came earlier, and he was so far removed from the action that he did not learn that the RIC officers had been killed until he almost back home. [18]

In Robinson’s account, needless to say, he was heavily involved in the ambush, in its planning and the execution. In this, Robinson is supported by other accounts. Michael Davern, later acting O/C of the Brigade, remembered seeing Robinson ten days before the ambush “elated with obviously suppressed excitement” at what promised to be the first Brigade operation. Anxious for its success and for people he could trust, Robinson invited Davern to join. Davern pleaded off but was able to mobilise four others instead. Like Treacy, Robinson was not adverse at delegating.[19]

One of these four, Patrick O’Dwyer, described who Breen and Treacy emerged from hiding to challenge the RIC escort to halt, with himself and Robinson grabbing at the reins of the cart-horse, before the officers attempted to open fire and were fatally shot instead, neatly matching Robinson’s record of the event. According to O’Dwyer, one of the policemen had been aiming his carbine at either him or Robinson before he was shot, making it clear that Robinson was risking his life as much as anyone.[20] Breen’s portrayal of Robinson as a mere tag-along must be taken with a hefty pinch of salt.

Robinson was not much more complimentary towards Breen. The party was lying in wait for the escort when Breen became agitated and impatient to rush out as soon as he could, prompting Robinson to make a mental note “that that man should never be put in charge of a fight.”[21]

Michael Collins

Both Robinson and Breen would insist later that the Soloheadbeg ambush had not been intended to be a simple robbery, but to provoke the public mood into war. If so, they got their wish. The ambush, along with the dramatic rescue of their captured colleague Seán Hogan at Knocklong Station, made the situation in South Tipperary too tense for Robinson, Treacy and Breen. Together, they left to take refuge in Dublin. Whatever Robinson thought of Breen and vice versa, they were to be stuck with each other for a while.

In Dublin Seumas Robinson was not impressed by Michael Collins’ efforts to assassinate John French, the Lord Lieutenant.

In Dublin, Robinson was to make the acquaintance of Michael Collins. It was not to be a harmonious working relationship. What aggrieved Robinson most was the failure of the first planned assault on Lord French, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. Collins assigned Robinson and Treacy to the last street corner before Dublin Castle on the route Lord French was to take from Dún Laoghaire. Should Lord French have survived the assassination attempts set up along the way, Robinson and Treacy were to ensure that the job was finally done.

After waiting until the latest estimated time Lord French was supposed to come, Robinson and Treacy saw instead Collins and a number of other senior officers walking towards them. Collins laughingly told the pair that Lord French was not coming after all. As far as Robinson was concerned, Collins had set up a dummy attack in the presence of other Volunteer leaders in order to give the impression of himself as the one leading the fight in the field.[22]

Robinson returned to Tipperary, refusing to join in any of the other attempts on Lord French’s life. The relationship with Breen also worsened. To Breen’s dismay, Robinson was no longer as amenable as before, to the extent of him issuing countermanding orders to those Treacy and Breen had already given to the Brigade. If Robinson had been intended to be a puppet, then he was becoming one determined to pull his own strings.[23]

It took both Treacy and Breen to persuade him to return to Dublin for what turned out to be the one assassination attempt that was followed through. Lord French survived, the only fatality being that of one of the attackers, Martin Savage, whose death affected Robinson deeply at the time, telling the news to others in a “broken voice.”[24]

Robinson’s impression of Collins as self-serving at others’ expense stayed with him. Three years later, Robinson was denouncing Collins during the Treaty debates in the Dáil as someone who had taken no risks but had urged others to do so.[25] The dislike was reciprocated. Shortly after his signing of the Treaty, Collins ruefully joked to Eamon O’Dwyer that bringing Robinson to Tipperary had been O’Dwyer’s worse mistake.[26]

Ernie O’Malley

Another GHQ mover-and-shaker whose acquaintance Robinson met was Ernie O’Malley. Robinson and Treacy first met him in Tipperary town, May 1920, at an officers’ class O’Malley was running; he was on one of his periodic trips across the country to better organise the various brigades. This time it was the turn of South Tipperary, which was the scene of a strong British military presence; Robinson and Treacy had had to fight their way through an enemy patrol on route to Tipperary town.[27]

O’Malley’s and Robinson’s memories of each other were generally respectful. The working relationship was comfortable enough for O’Malley to wish that Robinson had been made Commander of the First Southern Division instead of Liam Lynch.[28] For Robinson, O’Malley was a welcome change from the usual armchair generals who made up GHQ.[29]

Unlike Dan Breen, Ernie O’Malley appreciated Robinson’s abilities as a guerrilla leader

The two men had much in common. Both had literary tastes and aspirations, though it was only O’Malley who went the extra step and became known as a writer. Both were well-travelled throughout Ireland. Both were thinkers and organisers but unafraid to risk their lives in a fight. Both were serious-minded, hard-working revolutionaries, but who could be considered aloof and uninspiring by their subordinates.

Both ended up taking the Anti-Treaty side in the Civil War, an event Robinson had inadvertently predicted when discussing the newfangled IRA oath of allegiance with O’Malley and Treacy. Robinson had disapproved of the oath in how in it transferred authority from the army to Dáil, which might in the future accept something less than a republic. O’Malley and Treacy had laughed at the absurdity. Three years later, the Civil War would break out on that very issue. Robinson might have struck O’Malley as a bit of an Eeyore but, in this case, he had been a Cassandra.[30]

The Man Who Was Not There?

Together, Robinson, O’Malley and Treacy helped spearhead a series of coordinated attacks by the Third Tipperary Brigade on RIC barracks in South Tipperary. Not all of these were successful but they showed the ability of the Brigade to carry out sustained operations, a discipline nurtured by Robinson and Treacy, and a testament to their combined leadership.

Two of these assaults, on Hollyford and Drangan Barracks, are particularly noteworthy. Breen claimed in his memoir to have participated in them both. Robinson was to repeatedly insist in his BMH Statement that Breen had not even been present and had lied in writing that he had in order to inflate his reputation.[31]

A possible tie-breaker in this controversy is Ernie O’Malley, who helped lead the attacks on Hollyford and Drangan Barracks. O’Malley wrote accounts of his own, first in his 1936 memoir, On Another Man’s Wound, and later a series of articles in the mid-1950s that were published under Raids and Rallies.[32] In O’Malley’s accounts of the Hollyford-Drangan attacks, Breen does not appear in either. Had such a well-known figure like Breen been present at either Hollyford or Drangan, it would have been strange for O’Malley to have not made a mention of it, like he did of Breen’s presence at the assault on the Rearcross barracks, which Robinson did not deny. Thus we must tentatively conclude that Breen did lie about having been present at the Hollyford-Drangan attacks, and that Robinson was entirely correct in this.

Lepidus?

The extent in which Robinson held authority in his position as Brigade O/C was questioned by contemporaries. One such was Thomas Ryan, a witness to much that went on in the Brigade and a member of the second of the two Flying Columns which had been formed in late 1920. What Ryan had to say about Robinson’s leadership after the founding of the Columns is worth quoting at length;

From the time the Columns began operations, Robinson remained in and about the Brigade Headquarters…taking no active part in the work of the Columns, and so was not regarded by the men of the Columns as having any effective control of them…From this, it may be seen that we looked upon Robinson’s position as Brigade Commander as purely nominal.[33]

This passage has been cited as proof that, as a leader, Robinson was aloof and un-involved. However, Ryan was talking from the perspective of someone who was part of a very particular type of fighting unit, and his comments should be taken to reflect the changing nature of the IRA as the War progressed rather than Robinson’s leadership as a whole.

There was still much to do for the rest of the Brigade, over which Robinson continued to act as a hands-on O/C. In February 1921, Robinson was present with an ambush party alongside a railway embankment to catch a troop train. When the train did not arrive, Robinson gave a lecture before the men dispersed on the need for more activity for the War.[34]

During the Truce, in the expectation that the ceasefire would be temporary, Robinson funded an (ultimately failed) attempt to purchase from Germany the type of weapons, like trench mortars, that would help crack the nut that had been frustrating the IRA: British army garrisons.[35] Whatever the Columns thought of him, there was still a war to be fought, and he intended to continue doing his part.

Roads Not Taken

However, it does seem that Robinson struggled with maintaining the respect of his subordinates. Even Michael Davern, who was close enough to Robinson to introduce himself as Robinson’s right-hand man, had no compunction about talking back to him in a row over sloppy watchmen whom Davern had been responsible for.[36]

Another close colleague who did not automatically defer to Robinson was Eamon O’Dwyer. O’Dwyer’s discontent with the turn the revolution had taken was made embarrassingly public after the death of Seán Treacy in a shoot-out in Dublin in October 1920. Found on Treacy’s body was a letter by O’Dwyer complaining about the IRA use of ambushes, which quickly became grist for the British propaganda mill. Asked by Robinson to investigate O’Dwyer as a possible malcontent, Robinson stood by his friend, reporting O’Dwyer back as a man of integrity.[37]

Eamon O’Dwyer, who had introduced Robinson to Tipperary, was opposed to the guerrilla tactics employed in the conflict.

It was a generous act of loyalty on Robinson’s part, for O’Dwyer had also been actively undermining the war effort that was Robinson’s responsibility to maintain. O’Dwyer had been receiving calls from the families of Volunteers who were participating in the ambushes that had become the IRA tactic of choice, pleading for O’Dwyer to withdraw their men out of harm’s way. Concerned as to how much longer the War could be maintained anyway, O’Dwyer increasingly acceded to their wishes, and recalled fighting men back to their homes. When Robinson came to his house for an explanation, an angry and weary O’Dwyer refused to budge on the issue.[38]

Humane as O’Dwyer’s actions may have been, he was making Robinson’s job a harder one, with Robinson lacking the iron to discipline or dismiss his friend. It was a weakness in Robinson’s nature that Thomas Ryan noted and regretted. For all his disregard of Robinson as a leader, Ryan still respected him for his intelligence. Had the men in the Columns taken Robinson’s advice more often, and had Robinson made more of an effort to bond with them, then “they might have had less to lament in the way of lost opportunities.” But the fault in why they did not was due, in Ryan’s opinion, to Robinson not possessing a “more forceful character.”[39]

An example of one of these roads-not-taken was the choice of Seán Hogan as a Column Commander. Robinson had wanted Ryan in the role instead, and tried to persuade Ryan to put himself forward, but Ryan, content that Hogan would be suited for the role, refused. When Hogan proved to lack the necessary aggression to properly lead a Column, Robinson’s misgivings came back to haunt Ryan. As with the IRA oath of allegiance and its future repercussions, it was a case of Robinson understanding a situation better than anyone else but lacking the ability to lead people who did not already want to be led.[40]

Maintaining Discipline

The raids and rallies that have dominated the public perception of the War were only a facet in a wider picture. There was the intelligence war, with Volunteers urged to be on constant watch for informants. Robinson supervised the execution by shooting of an unmasked spy. This was a relatively straightforward case of an enemy agent tricked into blowing his own cover.[41]

Less obvious was the request made to Robinson by a Mid-Tipperary officer for permission to drive out a local family, the Hunts, so that their land could be divided up between Volunteers. As an afterthought, it was argued that, as a Protestant, Mrs de Vere Hunt, was too much of a potential spy. Robinson was not one to fall for such clumsy sectarian posturing, and instead gave orders that the Hunts were not to be troubled. Some months later, Mrs Hunt would prove the rumours entirely wrong by passing on information to the Volunteers from British officers who had dined at her house.[42]

Robinson was more merciful than some other IRA officers in Tipperary regarding the shooting of civilian informers.

About midsummer of 1920, Robinson felt the need to issue a request to his Brigade members (an order would have been too hard to enforce) that anyone caught inside a house where civilians were living should wait until outside before shooting. To Robinson’s dismay, many of his men “thought that the civilian population was at best a secondary consideration.” In response to this disturbingly blasé attitude, Robinson did his best to prevent the worst from happening.[43]

His concern for civilians in the crossfire caused him to veto a proposal to raze five houses of “well-known Unionists” in retaliation to the blowing up of houses by Crown forces in May 1921. Robinson’s stated reason was a refusal to stoop to enemy level. That people uninvolved in the War might have suffered may have also been a reason for Robinson’s reticence. After all, terms such as ‘Unionist’ were used rather liberally by Volunteers, often to indicate anyone who was a convenient target.[44]

Cattle-Raids and Rallies

Respect for civilian rights and property did not extend to the ‘IRA levy’ which was carried out on local farmers. Michael Davern was involved in the seizing of cattle belonging to ‘Unionists’ who had failed to pay the “very small” amounts demanded. Any money obtained in this process was intended to go into Brigade funds.[45] However, not every Volunteer was above exploiting this revolutionary racket for personal gain, a human failing that Robinson was not naïve about.

Near the end of July 1921, a court-martial was arranged for several Volunteers caught cattle-rustling. Robinson presided over the improvised court which found the defendants guilty. As for sentencing, the death penalty was suggested, though Robinson was persuaded against this on the basis that it might undermine Brigade morale. Instead, the considerably less severe punishment of supervised unpaid work was issued.[46]

Less spectacular than ambushes or barrack attacks were equally important activities for the IRA such as levying a ‘war tax’ and trying to maintain order ir areas controlled by the guerrillas.

As law and order collapsed throughout Ireland, the IRA brigades found themselves in the position of the authorities they had been fighting against. Brigade commanders were obligated to fill the vacuum they had helped create. Robinson took this new role of improvised policeman as seriously as he had taken that of local warlord, determined to curb the excesses of his subordinates. However badly the civilian populace of South Tipperary suffered from the War of Independence, it may have been much worse without the standards set by Robinson.

Robinson expected much from his subordinates, and did his best to rein in their baser desires, while sometimes struggling to elicit respect from them.

Conclusion

Séumas Robinson was elected O/C for the Third Tipperary Brigade, partly on the urging of Séan Treacy, but also on the basis of his participation in the Easter Rising and his considerable activism for the South Tipperary Volunteers. From there, he set about helping to create one of the more prominent brigades in the War of Independence.

A complex man, capable of the extremes of warm comradely and unreasoning hatred, Robinson worked with many of the leading figures in the revolution: with Michael Collins he had nothing but undisguised contempt for, Ernie O’Mally a respectful working relationship, Seán Treacy a fruitful partnership, and Eamon O’Dwyer unqualified loyalty even when O’Dwyer undermined him.

Robinson expected much from his subordinates, and did his best to rein in their baser desires, while sometimes struggling to elicit respect from them. A renowned brigade, a determination to fight for what he saw as a just cause and a respected civilian populace were the hallmarks of this proud, principled and often prickly man.

Bibliography

Bureau of Military History / Witness Statements

Beaumont, Séan, WS 709

Breen, Dan, WS 1739

Davern, Michael, WS 1348

Keane, Patrick, WS 1300

Keating, James, WS 1220

Lynch, Michael, WS 511

McGrath, Edmond, WS 1393

O’Dwyer, Eamon, WS 1403

O’Dwyer, Eamon, WS 1474

O’Dwyer, Patrick H., WS 1432

Robinson, Séumas, WS 1721

Ryan, Thomas, WS 783

Books

Ambrose, Joe. Dan Breen and the IRA (Douglas Village, Cork: Mercier Press, 2006)

Augusteijn, Joost. From Public Defiance To Guerrilla Warfare: The Experience of Ordinary Volunteers in the Irish War of Independence 1916-1921 (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 1996)

Breen, Dan. My Fight for Irish Freedom (Cork: Mercier Press, 2010)

O’Malley, Ernie. On Another Man’s Wound (Cork: Mercier Press, 2013)

O’Malley, Ernie. Raids and Rallies (Cork: Mercier Press, 2011)

Other Material

Ó Muirthile, Séan. UCDAD, Mulcahy Papers, P7a/209(2)

[1]O’Malley, Ernie. On Another Man’s Wound (Cork: Mercier Press, 2013), p. 432

[2]O’Malley, p. 183

[3]Breen, Dan. My Fight for Irish Freedom (Cork: Mercier Press, 2010), pp. 21-2, 30

[4]Breen, Dan (BMH / WS 1739), p. 21

[5]Ryan, Thomas (BMH / WS 783), p. 116

[6]McGrath, Edmond (BMH / WS 1393), p. 6 ; Davern, Michael (BMH / WS 1348), p. 10

[7]O’Malley, Ernie. On Another Man’s Wound, p. 180

[8]Robinson (BMH / WS 1721), p. 67

[9]O’Dwyer, Eamon (BMH / WS 1474), pp. 54-55

[10]O’Dwyer, Eamon (BMH / WS 1403), pp. 62-3

[11]O’Dwyer, Eamon (BMH / WS 1474), pp. 3-4

[12]Ibid, p. 25

[13]Ibid, p. 4

[14]Davern, Michael (BMH / WS 1348), p. 7

[15]Augusteijn, Joost. From Public Defiance To Guerrilla Warfare: The Experience of Ordinary Volunteers in the Irish War of Independence 1916-1921 (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 1996), p. 190

[16]Breen, My Fight for Irish Freedom, p. 40

[17]Ibid, p. 31-32

[18]Breen, Dan (BMH / WS 1739), pp. 21-23

[19]Davern, Michael (BMH / WS 1348), p. 15

[20]O’Dwyer, Patrick H. (BMH / WS 1432), p. 11 ; Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 1721), pp. 28-29

[21]Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 1721), p. 28

[22]Ibid, pp. 49-50

[23]Breen, Dan (BMH / WS 1739), p. 26

[24]Lynch, Michael (BMH / WS 511), p. 82

[25]Ó Muirthile, Séan. UCDAD, Mulcahy Papers,P7a/209(2), p. 85

[26]O’Dwyer, Eamon (BMH / WS 1474), p. 95

[27]O’Malley, Ernie. On Another Man’s Wound, p. 179

[28]Ibid, p. 432

[29]Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 1721), p.39

[30]O’Malley, Ernie. On Another Man’s Wound, pp. 182-3

[31]Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 1721), p. 87 as an example

[32]Breen, Dan. My Fight for Irish Freedom, pp. 107-110 (Hollyford), pp. 112-118 (Drangan)

O’Malley, Ernie. On Another Man’s Wound, pp. 189-195 (Hollyford), pp.200-203(Drangan)

O’Malley, Ernie. Raids and Rallies (Cork: Mercier Press, 2011), pp. 21-41 (Hollyford), pp. 42-60 (Drangan)

[33]Ryan, Thomas (BMH / WS 783), p. 116-117

[34]Keane, Patrick (BMH / WS 1300), pp. 5-6

[35]Beaumont, Séan (BMH / WS 709), p. 6

[36]Davern, Michael (BMH / WS 1348), p. 33, 45

[37]Ambrose, Joe. Dan Breen and the IRA (Douglas Village, Cork: Mercier Press, 2006), pp. 116-7

[38]O’Dwyer, Eamon (BMH / WS 1474), pp. 83-4

[39]Ryan, Thomas (BMH / WS 783), p. 117

[40]Ibid, p. 32, 79-80

[41]Robinson, Séumas (BMH / WS 1721), pp. 114-5

[42]Ibid, pp. 35-36

[43]Ibid, p. 57

[44]Davern, Michael (BMH / WS 1348), p. 58

[45]Ibid

[46]Keating, James (BMH / WS 1220), pp. 13-15