The Northern Ireland Conflict 1968-1998 – An Overview

In the latest in our series of overviews, a summary of ‘The Troubles’, by John Dorney

The Northern Ireland conflict was a thirty year bout of political violence, low intensity armed conflict and political deadlock within the six north-eastern counties of Ireland that formed part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

It was a complex conflict with multiple armed and political actors. It included an armed insurgency against the state by elements of the Catholic or nationalist population, principally waged by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) , though it also included other republican factions, with the aim of creating a united independent Ireland.

Arrayed against the IRA were a range of state forces –the Royal Ulster Constabulary or RUC, the regular British Army and a locally recruited Army unit, the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR).

The Northern Ireland conflict had elements of insurgency, inter-communal violence and at times approached civil war

Another angle of the conflict was sectarian or communal violence between the majority unionist or loyalist Protestant population and the minority Catholic or nationalist one. This was manifested in inter-communal rioting, house burning and expulsion of minorities from rival areas as well as lethal violence including shooting and bombing.

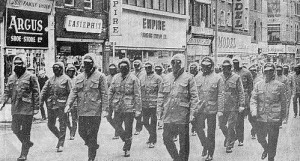

Arising from the loyalist community were a number of paramilitary groups, notably the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). Loyalist violence’s stated aim was to halt republican violence against the state but in practice their main target was Catholic civilians. Though not the principle focus of their campaign, republicans also killed significant numbers of Protestant civilians.

The IRA called a ceasefire in 1994, followed shortly afterwards by the loyalist groups, leading to multi-party talks about the future of Northern Ireland. The conflict was formally ended with the Belfast or Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

Definition

The conflict in Northern Ireland was generally referred to in Ireland during its course as ‘The Troubles’ – a euphemistic folk name that had also been applied to earlier bouts of political violence.

This name had the advantage that it did not attach blame to any of the participants and thus could be used neutrally. Republicans, particularly supporters of the Provisional IRA referred to the conflict as ‘the war’, and portrayed it as a guerrilla war of national liberation.

Unionists and the British government referred to the long running political violence as a law and order problem of ‘terrorism’. The London government portrayed the role of state forces as being primarily of peace-keeping between the ‘two communities’.

The death toll never reached 1,000 in a year, making it a ‘low intensity conflict’.

The violence never reached the most common currently agreed threshold of a ‘war’ – over 1,000 deaths in a year. Nevertheless its impact on society in Northern Ireland – an enclave with a population of about 1.5 million – was considerable, with over 3,500 killed and up to 50,000 injured over a thirty year period.

Origins

Northern Ireland was created in 1920 under the Government of Ireland Act, due to Ulster unionist lobbying to be excluded from Home Rule for Ireland. Northern Ireland comprised six north eastern counties of Ireland in the province of Ulster. It left out three Ulster counties with large Catholic and nationalist majorities (Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan) but included two counties, Fermanagh and Tyrone with slight nationalist majorities. Some areas along the new border such as Derry City and South Armagh/South Down also had substantial Catholic and nationalist majorities.

Northern Ireland’s existence was confirmed under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, that ended the Irish War of Independence. In 1925, a boundary commission that had been expected to cede large parts of Northern Ireland to the Irish Free State proposed no major changes. Even its limited modifications were never implemented and the border stayed as it was.

From 1922 until 1972, Northern Ireland functioned as a self-governing region of the United Kingdom. The Unionist Party formed the government, located at Stormont, outside Belfast, for all of these years. Its power was buttressed by a close association with the Protestant fraternal organisations such as the Orange Order.

Northern Ireland was created in 1920 for unionists who did not want to be part of a self-ruled Ireland, but contained a substantial minority of Catholic nationalists.

Catholics complained of systematic discrimination in Northern Ireland. Their voting strength was diluted by ‘gerrymandering’ –where Catholics were grouped in one constituency so they would elect a smaller number of representatives in proportion to their numbers. Additionally, in local government, only rate payers, who were more often Protestants than Catholics, had a vote.

Catholics also complained of discrimination in employment and the allocation of social housing, and also protested that their community was the main target of the Special Powers Act which allowed for detention without trial. The armed police forces, the Royal Ulster Constabulary and especially the Ulster Special Constabulary or ‘B Specials’, were almost wholly Protestant and unionist in ethos.

The unionists buttressed their political power with systematic discrimination against Catholics.

There was also a lack of official recognition of Irish nationality in Northern Ireland. The Irish language and Irish history were not taught in state schools. The tricolour flag of the Irish Republic was illegal, as was the Irish Republican party, Sinn Fein (from 1956 until 1974), though it organised in Northern Ireland under the names ‘Republican’ or ‘Republican Clubs’. However most nationalists in the North traditionally voted for the moderate Nationalist Party.

There was an ineffective, mostly southern-based IRA guerrilla campaign against Northern Ireland from 1956 to 1962, but with little nationalist support within the North and faced with internment on both sides of the border, it achieved little.

There were signs of a thaw in relations between north and south and between nationalists and unionists in the 1960s with reciprocal visits by Northern Ireland Prime Minister Terence O’Neill and Irish Taoiseach Sean Lemass, the first since 1922. O’Neill also proposed reforms within Northern Ireland. However O’Neill came under fierce criticism from unionist hardliners such as charismatic Presbyterian preacher Ian Paisley.

Civil Rights to armed conflict

In 1966 elements of the Northern Ireland Labour Party, radical left groups and the Republican Clubs founded the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association. Their aim was to end the discrimination against Catholics within Northern Ireland.

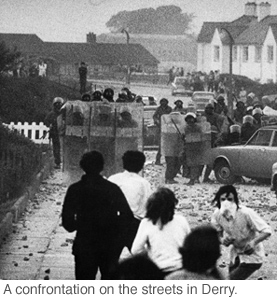

However violence regularly broke out at their marches, notably at a People’s Democracy march from Belfast to Derry which was attacked by loyalists. This led to increasingly bitter rioting between the Catholic population, especially in Derry, and the RUC. The unrest culminated in a series of severe riots across Northern Ireland in August 12-17, 1969 in which 8 people were killed, hundreds of homes destroyed and 1,800 people displaced.

Civil rights agitation from 1968 brought a violent response from the state and loyalists, culminating in severe rioting in August 1969

The rioting began over a loyal order march in Derry, after which rioting between police and Catholics – known as the ‘Battle of the Bogside’ – engulfed Catholic neighbourhoods. In Belfast, the rioting developed into street fighting between Catholics and Protestants during which an entire Catholic street – Bombay Street – was burned out. The RUC also fired heavy machine gun rounds at the mainly Catholic Divis Towers flat complex killing a young boy. The British Army was deployed to restore order and was initially welcomed by Catholics.

The riots marked a watershed. The IRA split into two factions, with the more militant, the Provisionals, claiming the existing organisation had failed to defend Catholics during the rioting. They were determined to launch a new armed campaign against Northern Ireland.

The other faction, known as the Officials favoured building a left wing political party and fostering unity among the Catholic and Protestant working class before attempting to achieve a united Ireland. However it was the Provisionals who would go on to dominate. More moderate nationalists coalesced in 1970 as the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) which was opposed to violence.

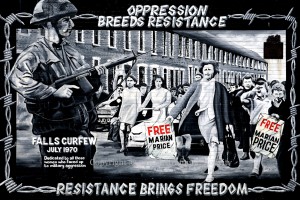

British troops were initially welcomed by Catholics as their protectors but were rapidly drawn into a counter-insurgency campaign against Republican paramilitaries.

The British Army’s relationship with the nationalist population quickly soured as a result of its efforts to disarm republican paramilitaries – notably the Falls Curfew of July 1970 in which it cordoned off the Lower Falls area of Belfast, engaging in several hours of gun battles with the Official IRA, killing four civilians and clouding the area in tear gas.

By 1971 both IRA factions were targeting the British Army. In response the Northern Ireland government introduced internment without trial – imprisoning 2,000 people between 1971 and 1975, over 90% of whom were republicans and less than 10% loyalists. In the initial sweep no loyalists at all were detained. Even those opposed to violence, such as the SDLP, walked out of the Stormont Parliament and led their supporters in a rent and rates strike. As a result, many republicans would depict the armed campaign of the following 25 years and defensive and retaliatory.

However it was also true that the Provisionals especially were determined from the outset to wage ‘armed struggle’ which they viewed as being the continuation of the Irish War of Independence. Unlike previous IRA campaigns internment was not introduced in the Republic of Ireland, leading unionists to allege that the southern state sympathised with republican paramilitaries.

The London government tried to defuse nationalist militancy with a series of reforms of Northern Ireland. The B Specials (auxiliary police in theory but in practice a unionist militia) were disbanded, electoral boundaries were redrawn to reflect Catholic numbers and housing and employment executives were set up to deal with discrimination.

Republicans and state forces were not the only source of violence. Loyalist groups also proliferated in the early 1970s with many Protestant neighbourhoods setting up paramilitary and vigilante groups. The largest of these was the Ulster Defence Association (or UDA, also referred to as Ulster Freedom Fighters or UFF) and the Ulster Volunteer Force (or UVF) founded in 1966. By 1972 both of these groups and others were killing significant numbers of Catholic civilians. Despite this, far fewer loyalist than republican militants were imprisoned.

The Insurgency phase

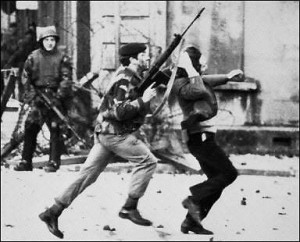

By far the worst year of the ‘Troubles’ was 1972, when 480 people lost their lives. The year opened with ‘Bloody Sunday’ in Derry in which 14 marchers against internment were shot dead by the British Army on January 30. This massacre gave massive impetus to militant republicans.

The Provisional IRA especially upped their campaign to its greatest intensity, killing over 100 British soldiers in that year and devastating the centre of Belfast and Derry with car bomb attacks – notably on ‘Bloody Friday’ on 21 July when 9 people were killed and 130 injured by 26 near-simultaneous car bombs.

The Provisional IRA went on the offensive in 1971-72, sparking off the most lethal phase of the conflict (1972-1976) and causing London to suspend the government of Northern Ireland.

The British Army characterised this period as the ‘insurgency phase’ of the conflict [1]. In addition to Bloody Sunday, its treatment of the nationalist population was often very violent – killing 170 people, many of them civilians, from 1971 to 1974. There were other incidents of large scale shooting of civilians such as the Ballymurphy shootings (11 dead in 1971) and the Springhill shootings (5 deaths in 1972).

It has recently emerged also that an undercover unit, the MRF, was carrying out assassinations and random shootings in Catholic areas and was responsible for at least 10 deaths, so some deaths attributed to paramilitary violence may actually have been undercover soldiers.

The Provisionals believed they were on the verge of victory by the summer of 1972, or at any rate British withdrawal, when the British government opened direct talks with the IRA leadership. In response the IRA called a brief ceasefire. However no political agreement was reached – the IRA proposed no terms other than a united Ireland – and, after a standoff with the British Army and loyalists in the Lenadoon area of Belfast flared up into violence, the ceasefire was called off.

Concurrently loyalist killings also spiralled. Their actions included pub bombings such as the McGurk pub bombing in 1971 in which 15 were killed and the abduction and shooting of random Catholics.

Yet another source of violence was spasmodic feuding between the rival republican factions. However the Official IRA called a ceasefire in May 1972, leaving the title of the IRA mainly to the Provisionals. Militant Official IRA members split off to form the Irish National Liberation Army, INLA, in 1974.

In the midst of this descent into violence the British government suspended the Northern Ireland Parliament and reintroduced ‘Direct Rule’ from London in March 1972.

The mid 1970s violence

By 1973 the many-sided conflict showed no signs of ending. Although the death toll fell from 1972 to 1973 (480 to 255) it remained high throughout the 1970s, with over 2,000 having died by the end of the decade.

The IRA began to back away from large scale armed encounters with British forces after their ‘no go’ zones of Belfast and Derry were taken by the British Army in a large operation known as Operation Motorman in July 1972.

The British military later characterised the ongoing IRA campaign as a move from ‘insurgency’ to ‘terrorism’, meaning that their actions henceforth were typically smaller scale and clandestine. They also took to bombing British cities.

The loyalist paramilitaries also became increasingly indiscriminate in the period 1974-1976 in which they killed over 370 Catholic civilians. Republican groups killed 88 Protestants civilians in the same period. Loyalists also began bombing towns and cities south of the border, notably in the Dublin and Monaghan bombs of May 1974, in which 33 people were killed.

State forces were also a major source of violence in the early 1970s as were loyalist paramilitaries.

There have been persistent allegations of ‘collusion’ of state forces in the loyalist campaign – RUC and Ulster Defence Regiment personnel certainly passed arms and information to loyalists and allegations exist that British Army intelligence was also involved in planning loyalist attacks. The Stevens Enquiry report of 2003 stated that it had found evidence of high level collusion between state forces including police, army and intelligence and loyalist groups.

The sectarian dimension of the conflict was brought under some control in 1976 with an agreement between republican and loyalist paramilitaries to cease using car bombs and targeting ‘enemy’ civilians (as reported by Eamon Mallie, Patrick Bishop, The Provisional IRA p 340).

From January 1975 to January 1976 the IRA was persuaded by the British government to call another ceasefire. However no political progress ensued and this had little appreciable effect on the level of political violence as republicans still killed 125 people and simply meant that IRA attacks were usually claimed with adopted names.

Sunningdale and the Ulster Workers Council strike

In 1973 a major effort was made by the British government to find a political solution to the conflict. In November of that year an agreement was signed between the major political parties (nationalist SDLP and the Unionist Party) in Northern Ireland, known as the Sunningdale Agreement.

It contained provision for power sharing between nationalists and unionists in a new regional assembly as well as a ‘Council of Ireland’ with the aim of developing all-Ireland cooperation.

The Agreement was brought down by massive grassroots unionist opposition. After the Unionist Party voted to ratify power sharing with nationalists in May 1974, mass protest rallies were organised Ian Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party and Vanguard led by William Craig. It was also during the period of the Sunningdale Agreement that loyalist paramilitary violence peaked.

In 1973-74 the British Government tried to set up a power-sharing Agreement between unionists and nationalists. It collapsed after massive loyalist protests.

Most significantly, the Ulster Workers’ Council – a body involving Protestant trade unionists as well as loyalist paramilitaries – organised a general strike across Northern Ireland including in power stations. Loyalist paramilitary roadblocks on all main roads prevented even those who did not support them from going to work. The two week strike caused the Unionist Party to pull out of the Agreement, making it null and void. There would be no further internal political agreements until 1998.

Nationalists were enraged that the British Army was not deployed to break the strike. In 1977 by contrast, when the Ulster Workers Council staged another general strike with the aim of forcing the restoration of ‘majority rule’, the strike was effectively broken by police and military action.

Ulsterisation, the Prison struggle and the Hunger Strikes

In the late 1970s, the British government, despairing of a political settlement, tried to find a security solution to reduce political violence to ‘an acceptable level’ in the words of one Northern Secretary.

In 1976 internment without trial was ended but convicted paramilitaries were treated as ordinary criminals. This provoked a grim struggle within the prisons.

Their strategy was to try to undermine the IRA’s claim that they were fighting a war of national liberation by two means. The first was so-called ‘, Ulsterisation’ – reducing the primacy of the British Army and returning it to the RUC police force.

The second strand was ending internment without trial – viewed to have been a public relations disaster – in 1976, and phasing in non-jury trials for paramilitaries. The aim was to have no ‘political’ prisoners but only prisoners convicted of criminal offences. They were to be housed, not in the Prisoner-of War type camp at Long Kesh but a purpose built prison – the Maze – situated next door. Moreover they were to be afforded no special treatment compared to ordinary criminals.

This led to  sustained protest by republican (and initially, some loyalist) prisoners for political status. They refused to wash or slop out their cells (the ‘dirty protest’) or to wear prison uniform (‘the blanket protest’). The protest culminated in the Hunger Strikes of 1981 in which 10 republican prisoners, led by Bobby Sands, starved themselves to death for political status.

sustained protest by republican (and initially, some loyalist) prisoners for political status. They refused to wash or slop out their cells (the ‘dirty protest’) or to wear prison uniform (‘the blanket protest’). The protest culminated in the Hunger Strikes of 1981 in which 10 republican prisoners, led by Bobby Sands, starved themselves to death for political status.

The Hunger Strikes ended up reviving the IRA’s flagging support in the nationalist community and across Ireland. The deaths of the hunger strikers proved their willingness to die and undermined the Government strategy of painting them as apolitical criminals. The prisoner Bobby Sands was elected to the British Parliament in a by-election during the strike, as, when Sands died, was Sinn Fein member Owen Carron. Two more hunger strikers were voted into the Irish Dail. There was widespread rioting in nationalist areas upon the deaths of the hunger strikers.

The ‘Long War’

Throughout the 1980s the conflict sputtered on. The IRA had a change of leadership in the late 1970s as southern leaders such as Ruari O Bradaigh were replaced by younger northerners such as Gerry Adams.

Adams and his colleagues devised a strategy known as the Long War, in which the IRA would be reorganised into small cells, more difficult to penetrate with informers and continue their armed campaign indefinitely until British withdrawal.

Parallel, they would win political support through their party, Sinn Fein. The election of hunger strikers was a major fillip to this strategy. In 1986 they decided to enter the Dail if elected. Their strategy was popularly known as the ‘Ballot Box and Armalite’ strategy after a speech by Danny Morrison.

Political violence went on throughout the 1980s but in spite of the IRA’s attempts to up its intensity, never reached the levels of the 1970s.

Political violence in Northern Ireland throughout the 1980s remained at a lower level however than in the 1970s. In only three years (1981,1982 and 1988) was the death toll over 100 and in 1985 there were only 57 deaths due to the conflict (see here).

The IRA in Belfast and Derry never regained the momentum they had had in the previous decade and were heavily infiltrated by informers. The organisation’s rural units in places such as South Armagh and Tyrone took on a greater importance through their continued ability to attack British forces with weapons such as mortars, improvised mines and heavy machine guns.

However many targets particularly of the part-time Ulster Defence Regiment were also killed while off-duty and unarmed. Bombings of civilian targets, particularly the Enniskillen bomb of 1987 in which 12 Protestants attending a war memorial service were killed, also damaged their popular support. Throughout the conflict Catholics voted in greater numbers for the SDLP over Sinn Fein.

The IRA also continued to attack targets in Britain and further afield, attempting to assassinate Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in Brighton in 1984 for example and blowing up 11 British soldiers on parade in London as well as Harrods department store. Three Provisional IRA members were killed while preparing a bomb in Gibraltor in 1988.

Despite importing significant quantities of heavy weapons from Libya in the mid-1980s, the IRA was able only to modestly increase the intensity of their campaign by the end of the decade. The exception to this was their bombing campaign in England. Importing large amounts of semtex explosive enabled them to detonate massively destructive bombs in commercial districts of London in the 1990s. Although these caused relatively few casualties due to warnings being given, the destruction of property in the financial centre of The City was enormous.

Loyalists, after a lull in the late 1970s, began killing large numbers of Catholics in the later 1980s – allegedly with police and Army ‘collusion’

Crown forces in the 1980s generally became much more careful to avoid killing civilians than in the preceding decade. There were however many allegations of targeted killings of IRA fighters – a so called ‘shoot to kill’ policy. For instance at the Loughall ambush in 1987 an IRA ‘active service unit’ of 8 men was wiped out. There were also serious problems with the use of rubber and plastic bullets to control riots, the deployment of which was responsible for 16 deaths, mostly Catholics, and many more injuries.

Loyalist violence lulled in the early 1980s but picked up again after the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985, in which the British government agreed to give the Irish government a consultative role in Northern Ireland. Loyalists, including a group linked to the Democratic Unionist party named Ulster Resistance, imported weapons from South Africa in response to a feared ‘sell out’. In some cases aided by British Army and RUC intelligence, loyalists began targeting republican militants and politicians for assassination. However, as in the 1970s most of their victims were unarmed Catholics.

By the 1990s loyalists were killing significant numbers of Catholics as well as republican activists. The IRA and other republican groups like the INLA and its off-shoots retaliated with attacks on loyalists, sometimes shading into attacks on Protestants such as the Shankill bomb of 1993 which killed ten people.

The Peace Process

By the late 1980s there were signs that republicans were looking for an end to the conflict. There were talks between Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams and SDLP leader John Hume and privately between republicans and the British and Irish governments.

By the late 1980s there were signs that republicans were looking for an end to the conflict. There were talks between Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams and SDLP leader John Hume and privately between republicans and the British and Irish governments.

In 1994 the Provisional IRA declared a unilateral ceasefire. This was followed six weeks later by a ceasefire from the main loyalist groups. The IRA broke its ceasefire in 1996 with a massive bomb in London, as a result of Sinn Fein not being allowed into negotiations before the IRA gave up its weapons.

The IRA and loyalists called ceasefires in 1994. In 1998 the Good Friday Agreement was signed.

In 1997 the IRA resumed its ceasefire and Sinn Fein was readmitted to talks. These also involved the nationalist SDLP and the Irish government as well at the Ulster Unionist Party, the Alliance Party the Progressive Unionist Party and Ulster Democratic Party (representing loyalist paramilitaries) and the Women’s Coalition. The Democratic Unionist Party, led by Ian Paisley refused to participate as long as Sinn Fein took part. These negotiations culminated in the Good Friday (or Belfast) Agreement of 1998.

The central plank of the Agreement was that the constitutional status of Northern Ireland would be decided only by the democratic vote of its inhabitants -known as the ‘consent principle’ – but that people from Northern Ireland would be entitled to both British and Irish citizenship.

This deal returned self-government to Northern Ireland but stipulated that government must be formed by equal numbers of nationalist and unionist ministers in proportion to their vote. Cross border bodies were established but the Republic gave up its territorial claim to Northern Ireland. The RUC police force was disbanded and replaced by the Police Service of Northern Ireland which had had quotas for the proportion of Catholic officers.

Under the Agreement unionist and nationalists had to share power. Police and state services were reformed. But it was 2007 before the parties could agree on a stable programme for self-government.

The Agreement was passed by referendum in Northern Ireland and a concurrent referendum in the Republic accepted the deletion of the claim to Northern Ireland from the constitution.

This was not however immediately the end of violence or of political deadlock. ‘Dissident’ republicans who split off to form the ‘Real IRA’ detonated a bomb in Omagh in 1998 killing 30 people. Various ‘dissident’ groups have attempted to mount armed campaigns to the present day.

There was also widespread rioting each summer for several years around Orange Order parades resulting in several deaths, notably around the Drumcree standoff (1996-2000). Loyalist groups also engaged in a number of internecine feuds, resulting in about 40 deaths up the mid 2000s.

The first Northern Ireland Executive (regional government) did not get up and running until 1999 and again collapsed in February 2000 as Unionist leader David Trimble refused to operate it while IRA weapons had not been decommissioned. It was re-established in May of that year but remained fragile and collapsed again in 2002.

Trimble’s position deteriorated as his Party lost electoral support to the DUP. At the same time Sinn Fein overtook the SDLP as the nationalist party with the largest vote.

The IRA did not destroy most of its weapons until 2005, when a large quantity of guns, explosives and ammunition were destroyed under international supervision. It also announced the definitive end of its armed campaign. In response the British Army began dismantling its fortified bases across Northern Ireland and withdrawing from active deployment there.

There followed more talks between Sinn Fein and the DUP which finally produced a deal whereby those two parties would form a new Northern Ireland Executive in 2007 with a DUP First Minister, Ian Paisley and Sinn Fein Deputy First Minister, IRA veteran Martin McGuinness.

By early 2010 all the paramilitary groups had undertaken some decommissioning. Currently Sinn Fein and the DUP share power in a restored Northern Ireland Authority.

Costs

The violence of the ‘Troubles’ is still open to partisan interpretation. Republican paramilitaries killed significantly more people than any other actor (some 2,000 of the 3,500 deaths). State forces were responsible for 368 deaths (including 6 by Irish state forces) and loyalists for over 1,000. (See here) Even if, as many republicans argue, state forces and loyalists had a high degree of cooperation, republican groups still killed more.

The ‘Troubles’ were less bloody than the previous conflict (1916-23) in 20th century Ireland but much bloodier than any other internal conflict in Western Europe since 1945.

This leads unionists to argue that the conflict consisted in the main of republican terrorism combated by a state constrained by the rule of law. They point out that by 1998 there were nearly equal numbers of loyalists as republicans imprisoned – 194 to 241. Statistics are hard to come by but estimates of the total number of republicans imprisoned over the conflict amounts to 15,000 and estimates of loyalists imprisoned range from 5 to 12,000.

However, Catholic civilians were significantly more likely to be killed than Protestant civilians, leading republicans to argue that their violence was legitimate warfare (as the majority of victims were state forces) whereas the loyalist campaign was simply sectarian murder.

Whether the conflict was a ‘war’ or a period of sustained ‘terrorism’ remains bitterly disputed.

Compared to the earlier conflict in 20th century Ireland (1916-1923) the violence was somewhat less intense. In the earlier period roughly 4-5,000 died over an 8 year period. And of these almost all but the 500 who died in Easter week 1916, died between 1920 and 1923. Moreover in the earlier period British state forces killed significantly more civilians than non-state forces, a pattern that was reversed in the Northern Ireland conflict.[2] However compared to comparable low intensity conflicts in Western Europe in the late twentieth century, such as the Basque Conflict, the Northern Ireland conflict was much bloodier.[3]

Legacy

It is widely considered that nationalists gained more from the peace process than unionists, as the unionist character of Northern Ireland was undermined, strict majority rule abolished and discrimination against Catholics reversed by quotas. However it is also true that republicans ended up putting aside their demand for united Ireland and working within a ‘partitionist’ settlement.

The old unionist dominated Northern Ireland has been swept away but it is far from clear what the long term future of the region will be.

The conflict caused a deepening of sectarianism, especially in working class urban areas where fortified ‘peace walls’ still separate Catholic and Protestant areas.

Paramilitary prisoners (about 450 people) who were affiliated to political parties which had signed up the Good Friday Agreement were all released in 1998. However a small number of ‘dissident’ republican prisoners (about 70) are still held under anti-terrorism legislation for acts committed since then. Moreover, as evidenced by the 2014 arrest of Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams for the murder of Jean McConville in 1972, there has been no amnesty for acts committed prior to the agreement.

Northern Ireland’s future remains ambiguous. Catholics now form an almost equal proportion of the population to Protestants. This has led many to predict a nationalist majority in the future with a consequent end to partition.

However the latest polls indicate that support for a united Ireland is not unanimous among Catholics, with 20% preferring to stay in the United Kingdom, 35% in favour of unity in 20 years and only 7% in favour of unification now. Support for Irish unity among Protestants is very low – at about 4%.

While these preferences may change, Northern Ireland remains closely tied to the United Kingdom economically. The conflict period damaged its economy greatly and also coincided with de-industrialisation in Western Europe which decimated its ship-building and linen industries. Over 30% of the workforce is directly employed in the public sector, compared with under 20% in Britain or the Republic. The Northern regional government is also heavily subsidised from London – raising £14 billion in taxes in 2011-12, for example but spending £23 billion.

Until the Republic (now heavily indebted) is able to make up this shortfall unification of Ireland would be extremely difficult. Thus the status quo appeared likely to remain for the forseeable future.

However, when, in 2016, the United Kingdom voted by referendum to leave the European Union, but Northern Ireland voted to stay, the status of the area was again thrown into doubt. The prospect of a resurrected ‘hard border’ between the North and the Republic, as well as the near parity in votes between nationalists and unionists in the 2017 Assembly elections, led to renewed calls by nationalists for a referendum on Irish unity.

In 2020, the British Government, led by Boris Johnson, as part of its withdrawal agreement from the European Union, agreed to a ‘Northern Ireland Protocol‘ in which Northern Ireland, alone among the UK’s constituent parts, would remain within the EU’s customs and regulatory area. This avoided a trade barrier within Ireland (as the Irish government and EU had insisted upon), but created a new ‘Irish Sea border’ between Northern Ireland and Britain. This led to a wave, of sometimes violent loyalist protests in early 2021.

Northern Ireland’s future remains uncertain.

Notes

[1] In which ‘Both the Official and Provisional wings of the Irish Republican Army (OIRA and PIRA) fought the security forces in more-or-less formed bodies. Both had a structure of companies, battalions and brigades, with a recognisable structure and headquarters staff. Protracted firefights were common. ‘

[2] In 1919-21 the IRA was responsible for 281 of the 898 civilian fatalities, with British forces being responsible for 381. A further 236 deaths could not be confidently attributed to any party (the IRA, loyalist, rioters, undercover Crown forces). [See Terror in Ireland, p153-154]

[3] The Basque conflict caused the deaths of about 1,000 people from 1968 to 2010, roughly 800 killed by the separatist organisation ETA and roughly 2-300 by Spanish state forces, in an area with a comparable population to Northern Ireland