Book Review: Aspects of Irish Aristocratic Life: Essays on the FitzGeralds and Carton House

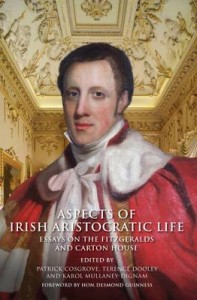

Aspects of Irish Aristocratic Life: Essays on the FitzGeralds and Carton House

Edited by Terence Dooley, Patrick Cosgrove and Karol Mullaney-Dignam

Edited by Terence Dooley, Patrick Cosgrove and Karol Mullaney-Dignam

Published by UCD Press, Dublin 2014,

Reviewer: Danial Murray

History, when you get down to it, is a study of the elite. Partly because they are important in a way that the rest of us are not, partly because the historical sources tend to focus on them, and partly because of the innate human fascination in those who seem to live in a higher plane of existence, whether due to fame, money or titles.

Social historians have heroically attempted to counter this bias by moving their studies away from the ‘great men’ towards recreating the lives of ordinary people. Judging, however, by the recent glut of popular history shows – The White Queen, The Borgias, The Tudors, among others – and their cast of blue-blooded characters, this interest is unlikely to wane or be replaced any time soon.

This book is a collection of essays on the Fitzgerald family and how the dynasty fared throughout Irish history.

This collection of essays – nineteen in all – covers the Fitzgeralds, the pre-eminent noble family in Ireland and the Earls of Kildare. Maynooth and Carton House, as centres of the family power in different ways, also feature prominently, with chapters on the development and the early college of Maynooth and on the landscape, servants and material life of Carton.

The strengths and weaknesses of this book stem from the same root: the number of contributors and their varying specialisations means that reading the book cover-to-cover can either be enjoyed as a kaleidoscope of personalities, politics and home comforts or a disjointed mismatch.

Alternatively, readers could skip to the chapters that promise the most interest. This reviewer’s interests include the Middle Ages, biography and early 20th century history, and so the first chapters read were the ones on the Middle Ages, Lord Edward Fitzgerald (he of the United Irishmen fame), and Lord Frederick FitzGerald and his role in Kildare politics until his death in 1924.

The three essays by Mary Ann Lyons, Carol O’Connor and Colm Lennon cover the family from its peak as chief magnates of Ireland in the 15th-16th centuries, securing the country on behalf of the English Crown, though that did not mean they were above staging ‘revolts’ whenever threatened with supplanting by some upstart appointee from England to ‘prove’ that only they could control the unruly island.

This trick was tried too often with Henry VIII who almost exterminated the family in response and cast them out in the political wilderness. It took the shrewd diplomacy and alliance-building by Mabel Browne, who married into the family, to restore the Fitzgeralds to royal good fortune.

The Fitzgerald legacy would then be the battleground of politically motivated historians who depicted the clan as either the natural rulers of Ireland or despicable traitors.

The Fitzgerald legacy would then be the battleground of politically motivated historians who depicted the clan as either the natural rulers of Ireland or despicable traitors. The three essays that encompass all of this do an excellent job of narrating the family’s rise and fall and hard-won rise again, providing a coherent picture that overlap on certain points without clashing.

Liam Chamber’s ‘Family Politics and Revolutionary Convictions,’ on Lord Edward FitzGerald, has more of the latter than the former, his family largely absent. The essay is straightjacketed by its short length of eight pages, and while that is not unusual compared to the other essays, it means that the end result falls short of its ambition.

Chambers draws attention to how the historiography on Edward had been shaped by early writers like Thomas Moore, Charles William FitzGerald and Gerald Campbell, who were able to make use of the family private papers. The historians who followed them lacked such access and so were limited to quoting the papers from the earlier works.

Since the 1990s, the National Library of Ireland acquired thousands of manuscripts relating to Edward and his kin, allowing modern historians to finally see these materials for themselves. Other than that, Chambers has little to say, and the essay’s length limits him to ‘telling’ rather than ‘showing’ as a writer.

Thomas Nelson’s look at Lord Frederick Fitzgerald (1837-1924) is hampered by how very little is known about the man. He left few papers and none of a personal nature, so Newton resorts to other sources such as local newspapers and government papers to present a view of the Fitzgerald estates in Kildare during Frederick’s ownership. After five years serving in the British army in India, Afghanistan and South Africa, Frederick came into his Kildare estates at an awkward time.

Thomas Nelson argues that Fitzgeralds maintained a good relationship with their tenants throughout the Land War of the 1870s and 80s.

The Land War was under way, though Nelson argues against the usual depiction of the landlord-tenant relationship breaking down in light of he local enthusiasm received by Frederick upon his return from abroad and at the marriage of his sister. Frederick was able to negotiate with his tenants in a satisfactory manner so that Kildare avoided the worst virulence of the Land War.

This ability to maintain local support continued when he was elected to the country council in 1899 at a time when landlords were increasingly depicted as colonial oppressors.

This book is best consumed by concentrating on the chapters that most interest the reader.

Frederick remained on the council for the next twenty-one years, winning each election that came his way until 1920, when he stepped down from any further role in politics. As a sign of the times, his replacement was Daniel Buckley, a Maynooth shopkeeper who went by Domhnall Ua Buachalla and represented Sinn Féin.

While short on personal detail about Frederick FitzGerald – other than an excessive fondness for his female servants leading to a high staff turnover rate – Nelson handles what is usually a dry topic in a clear, detailed and engaging way.

To have the book for only a few select chapters may seem a waste, however, particularly at its less-than-commercially-friendly price (an eye-watering 45 euro on the publisher’s website at this time of writing). The ideal readership are probably students who can access their university libraries.