The Sinn Féin Rebellion? Arthur Griffith’s Easter Week 1916

Gerard Shannon on Arthur Griffith, Sinn Féin and the insurrection of Easter 1916.

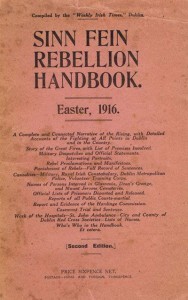

‘The Sinn Féin Rebellion’ became a popular, though paradoxical, term given to the 1916 Easter Rising during its aftermath.

A commemorative photographic album published by the Irish Times after the insurrection is one such example of how this name was cemented in the popular imagination of the Irish public[1] – and likely even further in the eyes of an unimaginative and confused British administration in Ireland.

The Easter Rising was popularly termed the ‘Sinn Féin Rebellion’ but what was the real role in it of the party and its leader Arthur Griffith?

However, though the Sinn Féin party had certain leadership figures and other combatants amongst its ranks, as an organised body it had absolutely no involvement in the planning or fighting on the rebel side.[2] By the time of the Rising, over a decade since its founding, Sinn Féin was regarded as miniscule, separatist movement on the fringe of Irish nationalist politics; public support mainly given to the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party.

Sinn Féin’s later association with violent revolution was unusual given the party’s origins, most especially given the ideology espoused by the man who founded it, Arthur Griffith; an avowed Irish separatist and notable figure in advanced Irish nationalism.

By 1916, Griffith was a noted political activist and self-published journalist who wrote passionately and skillfully about matters of Irish nationalism, politics, culture, and – above all – the flaws of British rule in Ireland in many, often banned pamphlets, newspapers and books. Criticisms of the Irish Parliamentary Party were a frequent theme in Griffith’s articles, thereby positing him outside mainstream politics, and making him more of an advanced nationalist.

His own radical nationalism he articulated into theories collected in his most celebrated work, The Resurrection of Hungary. Here, Griffith detailed ideas of passive (non-violent) resistance and economic self-sufficiency, in the latter chiefly drawing on the work of the German economist, Frederick List.

Griffith’s most striking idea however would be that of withdrawing Irish representatives from Westminster to form an independent Irish parliament based in Dublin; with the British monarch still reigning as the head of state. Drawing on the historical example of Hungary within the Austrian empire in the mid-19th century, this ‘dual-monarchy’ concept was a crucial plank in what became known as the ‘Sinn Féin’ policy that Griffith hoped would appeal to both nationalists and unionists. (Sinn Féin being an Irish phrase for ‘Ourselves’ sometimes translated as ‘Ourselves Alone’).

Arthur Griffith was an advocate of non-violent passive resistance to secure the separation of Ireland from Britain.

Though Griffith was not opposed to the idea of an independent Irish republic – a popular separatist idea since the period of the United Irishmen – he felt to avoid partition, a dual monarchy system in Ireland would be the most acceptable to both nationalists and unionists.[3] How much stock Griffith ever put in the notion of an independent Irish republic as a political goal is a recurring theme in many biographical works about him.[4]

Since he first articulated his Sinn Féin concepts in 1905, his failure in the decade since to unite moderate Home Rulers and radical nationalists did not deter his belief in the long term of the validity of this theory of abstentionism and passive resistance. As the historian Michael Laffan best puts it, Griffith became “the most fervent convert” to his own ideas.[5]

However, if not his ideas, then the acknowledged brilliance of his writing would become a recurrent theme in firsthand accounts of the period. C.S. Andrews summed up Griffith for many as “a voice crying in the wilderness of national apathy.”[6] Kevin O’ Shiel, who would later be a Judicial Commissioner in the Dáil Courts, felt Griffith was a “master of a superb and enviable prose style – simple, concise and as clear and fresh as a spring well.”[7]

Though he became the focus of Griffith’s emnity during the later Treaty debates, Erskine Childers, would still feel compelled to write in an obituary that Griffith was “the greatest intellectual force stimulating the tremendous national revival which took shape in Easter Week.”[8]

By the beginning of Easter Week, Arthur Griffith made clear in words and action he was deeply opposed to the Rising

In spite of this, by the beginning of Easter Week, Arthur Griffith made clear in words and action he was deeply opposed to the Rising, or indeed, to any kind of violent revolution against British rule in Ireland – consistent with the development of his Sinn Féin policy.

However, this did not make Griffith in the traditional sense a pacifist, as certain contemporaries point out. P. S. O’Hegarty, for instance, felt Griffith was “a physical force man of the old philosophic school, which held that physical force was permissible and necessary, that Ireland would eventually gain her independence only by means of it, but which held also that a Rising by a minority was unjustifiable … “[9]

Writing only two years after his Griffith’s death, George Lyons felt that “some recent fiction has written [Griffith] down as a mild and timid man.” He goes on further to say that Griffith was “not afraid of war. Though he abhorred militarism, he readily consented himself to action when such became necessary or feasible.”[10] Lyons also places emphasis on Griffith publicly supporting many IRA actions against British forces through the War of Independence from 1919 up until the Truce of 1921.[11]

Ultimately, one of Griffith’s most recent biographers, Brian Maye, felt that when it came to physical force, that when it came to weighing Griffith’s words and actions it “is not immediately clear… whether [Griffith] was opposed to it’s use on practical rather then principled grounds (believing it justifiable in certain circumstances)”.

To demonstrate this ambiguity, Maye points out Griffith was a greater admirer of Irish constitutionalists like Jonathan Swift and Henry Grattan, while also of revolutionaries like Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmet.[12]

Given this ambiguity into his thinking on physical force as a revolutionary instrument, Griffith’s own actions during the events of Easter Week 1916 are worth looking at in detail.

Griffith, the IRB and the Irish Volunteers

By 1914, Griffith maintained a close association with the secret society known as the Irish Republican Brotherhood, otherwise known as the IRB. The IRB itself shared membership with many of those in Sinn Féin, and over the previous decade had funded several of Griffith’s publications. Though he had joined the group at the outset of his political activism in the 1890s, Griffith himself had not been a member for several years, ultimately preferring his own independence but also more keen on building up a political profile for the Sinn Féin party.[13]

Ironically, because of his more direct involvement in Sinn Féin, Griffith’s standing in advanced nationalist circles had diminished since 1910. During that year, as leader of Sinn Féin, he took the decision to have the party stand aside in several by-elections. Though Griffith had little time for the Irish Parliamentary Party, he did not wish to disrupt the seeming inevitably of the success of its Home Rule campaign, feeling his own party could perhaps play a part in a new national parliament.[14]

Griffith had a close relationship with the Irish Republican Brotherhood but was not a member and clashed with them on various issues.

This stance almost certainly resulted in the departure of more radical, younger nationalists from the party, who by then already took issue with other aspects of Griffith’s autocratic style of leadership.[15]

In 1912, Patrick Pearse critiqued Griffith’s influence on Sinn Féin at this point in the form of an open letter published in Pearse’s political weekly, An Barr Buadh:

“You were too obstinate… too narrow-minded… You over-estimated your own opinion. You distrusted people who were as loyal as yourself. You would follow no-one’s advice except your own. You preferred to prove to the world that no one else was right except yourself… No progress was possible for an association which had that kind of man at it’s head.”[16]

Not surprisingly, Pearse never joined the party, though he was present when Griffith first presented the Sinn Féin policy in a speech in 1905.

By the outbreak of war in Europe in mid-1914, the current secretary of the IRB Supreme Council, Thomas Clarke convened a meeting of people ‘representative of advanced national opinion’ in the headquarters of the Gaelic League, where Griffith was present with other notable figures outside the political mainstream. It would appear that the prospect of a national rising was at least mooted, though not agreed on. Also, a second meeting was to have taken place, which never occurred.[17]

In September 1914 the Supreme Council of the IRB approached Griffith to join. Griffith refused and was frozen out of their secret plans for insurrection.

In September 1914 the Supreme Council of the IRB approached Griffith to join. Griffith refused, preferring to maintain his own independence in his publications, but feeling his stance on the war and IPP would compliment their work.

However, he seemed to believe he had secured an agreement from Tom Clarke and Seán Mac Diarmada [aka Sean MacDermott] – as Secretary and Treasurer of the Supreme Council respectively – that they would inform him of any development in the planning of an insurrection. As later events would prove, Griffith appeared to take this promise very seriously.[18]

Clarke and MacDiarmada by early 1915 had formed a Military Committee within the IRB to plan such an insurrection, with the hope the nationalist paramilitary body, the Irish Volunteers, could be used to ensure its success. The Chief-of-Staff, the cultural nationalist and writer Eoin MacNeill, was not a member of the IRB, though many on the Volunteer executive were.

“As long as the Volunteers remain on the defensive we are winning. The only thing that would ruin us would be to take offensive action.” Arthur Griffith, 1914.

Griffith himself has whole-heartedly supported the Volunteers on their founding in November 1913, seeing its formation as laying the groundwork for a national army. Though not on the Volunteer executive, Griffith joined a company as a private, and was later present at the landing of arms by the Asgard in Howth on 26th July, 1914.

When it came to the prospect of the Irish Volunteers leading any kind a revolution at that point in time, Griffith said to Piaras Beaslaí prior to Easter 1916: “As long as the Volunteers remain on the defensive we are winning. The only thing that would ruin us would be to take offensive action.” Beaslaí, of course, was an IRB member well aware of Clarke and Mac Diarmada’s conspiracy. He felt that Griffith “sounded like the voice of common sense dispelling romantic dreams.”[19]

Stop The Rising

Griffith had developed a friendly association, if not necessarily a close friendship with Sean Mac Diarmada over the several years leading up to 1916. Mac Diarmada had become a major organiser for Sinn Féin branches across the country – while also as a chief recruiter for the IRB – which brought him into frequent contact with Griffith.

Griffith later told his friend, Robert Brennan, that he had noticed in the week preceding Easter Week 1916 MacDiarmada had been unusually active in the Sinn Féin offices and been receiving many visitors.[20] In any event, it would be the future Irish President, Sean T. O’Kelly, then a prominent Sinn Féin activist, who would first inform Griffith of major developments related to the Rising.

Griffith was shocked and surprised by the scuttling of the Aud and the capture of Roger Casement as he had been kept out of the plans fro the Rising.

‘‘On the afternoon of Saturday, April 22nd, O’Kelly approached Griffith in Ridgeway’s barbershop, then in the basement of Purcell’s tobacconist store at the corner of Westmoreland Street and D’Oiler Street. There, O’Kelly informed Griffith of the scuttling of the Aud, and Roger Casement’s capture and arrest in Kerry the previous day. O’Kelly noted Griffith was “greatly shocked and wondering what the meaning of it was.”

As they left the barber’s, Griffith made a “bitter complaint” to O’Kelly of how Clarke and Mac Diarmada had promised to keep him informed of any insurrection; being “very hurt that Clarke and MacDermott had not taken him, according to their promise, into their confidence.”

Suspicious at these turn of events, both men made their way by taxi to the Rathfarnham home of James MacNeill, brother of the Volunteers’ Chief-of-Staff, Eoin MacNeill. There, they found Eoin MacNeill was already drafting countermanding orders to Volunteer units in the country to disrupt the IRB conspiracy.’ [21]

MacNeill directed O’Kelly and Griffith to go the house of a sympathiser to the Volunteers, Dr. Seamus O’Kelly (no relation), based Rathgar Road that night where there would be a gathering of his own allies on the Volunteer executive.

Griffith himself arrived at the house on Rathgar Road at around 10pm. Liam Ó’Briain met Griffith there, then a member of the Volunteers and IRB. (Though Ó Briain, not alone in the IRB ranks, was unaware of the Military Committee’s plans). Ó Briain recalls Griffith standing with his back to the fire, putting in an “occasional murmur of assent or very brief comment.”

Griffith fully backed the efforts of volunteer Chief of Staff Eoin MacNeill to call off the Rising.

O’Briain felt many of those present seemed almost frightened by the escalating situation, with the exception of Griffith, “who seemed almost as usual, certainly far cooler and more ‘normal’ than anyone else – like himself when he was very serious, thinking hard and keeping rigidly cool and very taciturn – a mood that all his old friends will remember well.” Griffith clearly was in agreement with the cancellation of manouveres as desired by MacNeill.[22]

That Griffith eagerly planned to assist MacNeill is not surprising in respect of his prior beliefs on violent revolution. Yet, Griffith’s friend, George A. Lyons, wrote that Griffith’s lack of support for the Rising was chiefly down to him not only being “reserved for political, historical and diplomatic reasons”; but that these ideological concerns “became all the more imperative on the disappearance of Casement.”[23]

The house owner, Seamus O’Kelly would recall the surreal sight of so many well known public figures crowding into his house on that evening. He observed MacNeill and Griffith signing some of the countermanding orders in his front room at one point. (While Griffith probably assisted in preparing the orders, it’s unlikely he signed any, given his lack of leadership role in the Volunteers).[24]

On Easter Sunday, Griffith made his way to Bray to issue MacNeill’s countermanding order to Joseph Kenny, a Captain in the Volunteers (as well as a member of the IRB). Kenny would recall how he met Griffith that morning outside Sunday mass.

Earlier, Griffith had previously called to Kenny’s family home that morning and in Kenny’s absence talked to his servant girl. Though Griffith did not give his full name, Kenny, mindful of the authorities, later prevailed on the young woman to agree to say she never encountered Griffith at Kenny’s front door.

Kenny directed Griffith to wait until they reached the local train station to hand him the order as Kenny suddenly noticed a police spy at the church gates. Griffith then handed Kenny the order and instructed him to take it to the Secretary of the local Volunteer company.[25] This appears to have been Griffith’s sole involvement in issuing MacNeill’s countermanding order.

The Rising

By Monday, April 24th, with Sunday having passed without any incident instigated by the Volunteers, it appeared to Griffith that the insurrection had been successfully halted through the efforts of himself and the rest of MacNeill’s allies.

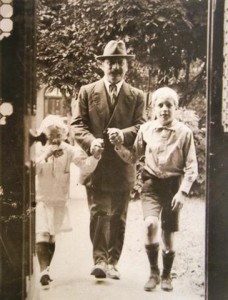

In the meantime, Griffith’s wife, Maud, decided to take advantage of the reduced train rates for the Easter weekend to go to Queenstown, to see off a visiting sister who would depart from there on a ship to America, while her husband would looking after their two young children, son Nevin and daughter Ita, for the day.

In her BMH witness statement, Maud recalls her husband warning her not to go prior to the cancellation of the Volunteers’ manoeuvres, only deciding to go to Cork early on Easter Monday when that had seemingly occurred.[26] It was to be strictly a day visit, mainly due to the Griffiths’ limited finances and Maud had never intended to stay even one night in Cork. Of course, due to the fighting beginning in Dublin, normal train services back to the capital were abruptly cancelled.[27]

Unaware of this, late on Monday afternoon, Griffith decided to bring the children to visit their grandmother when a series of shots were heard some distance away that sounded more considerable then what may have been typical for shooting practice.[28]

When the Rising unexpectedly broke out on Easter Monday, Griffith tried to hide his children with neighbours for fear of reprisals, most refused.

Maud Griffith says neither Griffith and their children had reached the end of their road when her husband was informed – we do not know by whom or how – of the beginning of the insurrection.[29] Bulmer Hobson, a formerly prominent IRB figure who tried to stop the Rising, later met Griffith in the week. Hobson recalled Griffith was informed by a mobilisation order issued to him as a member of the Volunteers, which of course he disobeyed.[30]

Griffith’s first priority, understandably, was the welfare of his children before investigating any further. However, he quickly found he was unable to get any of his neighbours to agree to take Nevin and Ita in his absence, being turned away in most cases. As the full scale of the activity in Dublin became known, the assumption with some of Griffith’s neighbours appeared to be that the trouble being caused by the ‘Sinn Féiners’ (a popular term for the Volunteers, however inaccurate) was somehow related to him.[31]

However, not all of the refusals to take the Griffith children seemed to have been due to this, Maude Griffith recalls one unnamed neighbour who deliberately tried to keep her husband in the family home, so as to protect him from the danger of venturing into the city.[32]

It was at some point on Monday that Griffith opted to send a message to Sean Mac Diarmada, who he seemed to have been aware was based with the garrison in the GPO. In the message, Griffith told Mac Diarmada “what he thought of them” for not keeping him posted on the insurrection plans, seeing it as breaking the earlier promise by the Supreme Council to him in September 1914. And yet in light of his anger, Griffith was now eager to stand alongside the Volunteers in the fight.[33]

While it’s unclear how this message reached the GPO, it was likely not by Griffith going there in person as is only ever vaguely suggested in several secondhand accounts.[34]

There is the account of Gearoid O’ Sullivan, then a Volunteer stationed in the GPO, who told Liam Ó Briain that Mac Diarmada mentioned: “We have got a very nice letter from Griffith” and further indicated that Griffith’s offer to join in was appreciated, and the reason behind his anger was understood.[35]

However, the collective decision of the rebel leadership – or at least that of Mac Diarmada – was that they did not wish for Griffith to be present in the GPO or to take part in the fighting, conveyed in some sort of a message sent around Wednesday. Rather, that it was more important for Griffith’s “pen and brain to survive” and continue his work, and “to some day defend and justify them.”[36]

Though opposed to the Rising, once it was underway Griffith tried to persuade Eoin MacNeill to issue a proclamation to the Volunteers for a nationwide insurrection.

Maude Griffith recalls Sean Mac Diarmada expressing similar sentiments in a letter to her husband that was smuggled out of Kilmainham Gaol – in which he also asked for Griffith’s forgiveness for not having kept his earlier promise.[37]

In any case, Griffith eventually managed to resolve the issue with his children by mid-week, helping them over the rear garden wall to a sympathetic neighbor’s residence – one biographer, Padraic Colum, believing this was due to Griffith’s suspicions the family home was now being watched.[38]

Having resolved the issue of his children’s well-being by Wednesday, Griffith was able to get to Eoin MacNeill’s home in Dundrum to discuss the accelerated rate of developments.[39]

Having procured a bike, Griffith decided to take a somewhat roundabout way to MacNeill’s home to avoid the city centre. Having made his way north of the Liffey from Clontarf, he then crossed the river at Lucan and then made his way to the southside of the city to the MacNeill residence.

As he cycled on, Griffith later conveyed to his friend Oliver St. John Gogarty he feared what his children would think of him if he was captured and not near the fighting.[40] Indeed, Robert Brennan recalled Griffith telling him of “the agony” he felt cycling through the Dublin streets: “He feared he might be taken and that it would be represented he was running away from the fight. On his way back to the city, he was almost happy and made up his mind that the Rising should be made a National one at all costs.”[41]

Having safely reached MacNeill, the two men talked late into the evening, and concluded only a national rising of the Irish Volunteers could help the rebel units in Dublin. For this to occur, the best approach would be a proclamation to be issued and signed by both Griffith and MacNeill, with the former taking to the country to issue it to the Volunteer units. However serious this plan was, the fighting in the city made would have made printing such a proclamation difficult, and indeed, by the surrender on Saturday, a moot notion.[42]

When Liam Ó Briain was writing a retrospective article on the now-dead Griffith in late 1922, he sought out Eoin MacNeill – then Minister for Education in the Provisional Government – to clarify details of this intriguing exchange. MacNeill confirmed that a possible proclamation to be issued to the Volunteers in the country was discussed between him and Griffith, but was also never written up. Ó’Briain concurred, concluding also it was difficult to believe Griffith would be foolish enough to leave MacNeill’s home with such a dangerous document on his person that would never be put to any use.[43]

Griffith himself seems to have told Robert Brennan that “other counsels” prevailed against issuing a proclamation.[44] There is also the account of Maire O Brolchain, that suggests Griffith vaguely hoped MacNeill might change his mind on the matter. Marie’s husband, Padraic, then active in the Volunteers, visited Griffith to prevail on him to issue a national proclamation.

Griffith told him that he had already attempted to talk to MacNeill on the Wednesday about a national rising. O’Brolchain felt Griffith supported his own attempt to talk MacNeill into rallying a national rising of the Volunteers, but he was also unsuccessful.[45]

Having managed to get his wife and children to safety, Griffith was persuaded to sit at home and wait for the inevitable arrest.

As the week progressed, Griffith’s wife, Maud, was helped by a kindly, unnamed priest who found her somewhere to stay in Cork.[46] She frequently went to the station in Queenstown in the hope a train would run. The priest later brought her to the Volunteers HQ in Cork city at one point, where she met both Volunteer leaders Tomas MacCurtain and Terrence McSwiney, recalling the latter “was in a terrible state of anxiety as he did not know what to do, having got conflicting instructions from Dublin.” It was only by Saturday that she was able to get one train that allowed her to get back to Lucan.[47]

The train was stopped by the Dublin Castle secret service at a station outside the city. While each of the passengers were scrutinised on the platform, Maud was surprised that a detective who frequently followed her husband did not appear to recognise her.[48]

Finally reaching the family home later that evening, she was delighted to find her entire family safe on her return. However, it was only inevitable that Griffith would be arrested following the rebel surrender early on the Saturday. Indeed, MacNeill had advised Griffith the best approach for them both was to just sit in their homes and wait out the inevitable arrest, with Griffith agreeing.[49]

In this respect, the reasoning behind this decision for Griffith was likely similar to what MacNeill had expressed to Bulmer Hobson when the latter faced a similar predicament: “MacNeill told me that we would have no political future if we were not arrested… “[50] In any event, given Griffith’s propaganda being well known to the authorities – not to mention his association with the Sinn Féin name – it was likely at some point he would be arrested.[51]

Aftermath

Griffith would leave behind a striking account of his reaction to the executions of the Rising’s leaders, many whom, such as Clarke and Mac Diarmada he had known in activist and political circles, and others such as the Boer War veteran John MacBride and the socialist James Connolly, he had known as friends.

“Something of the primitive awoke in me… I clenched my fists with rage and longed for vengeance. I had not believed they would be stupid enough to do it. Had I foreseen that, perhaps my views on the whole matter might be different.”[52]

Whatever his ideological disagreements, Griffith’s sentiments were firmly on the side of those who had fought in the Rising following his imprisonment and subsequent deportation with other detainees to England. In November 1916, from Reading Prison in England, Arthur Griffith wrote an angry, though firm letter to the MP Arthur Lynch, a member of the Irish Parliamentary Party.

Lynch made an intercession on behalf on Griffith in Parliament, emphasising Griffith should be released as he had no part in the rebellion of several months before. Griffith had issues with Lynch over political differences in the past, though was incensed as this development.

Whatever his ideological disagreements, Griffith’s sentiments were firmly on the side of those who had fought in the Rising and was imprisoned in its aftermath.

Griffith wrote: “I gave to you nor to any other member of that body no authority to put questions concerning me in the British Parliament. Your action is reprehensible – your questions I regard as an insult in their suggestion that I dissociate myself in any way from the action of my brother-Irishmen, now dead or in prison, and in suggestion of what you term compensation.” Griffith goes on further to suggest Lynch and other IPP colleagues do not speak on his behalf until himself he can do so.[53]

With the amnesty given to most Irish prisoners in late 1916, on his return to Dublin, Griffith was eager to revive the Sinn Féin policy in new publications.[54] Griffith also remained as leader of the newly popular Sinn Féin through many successful by-elections in the months ahead; but now he and his allies had to contend with an influx of young radicals in the ranks – many of whom shared membership in the similarly revived Irish Volunteers.

Michael Collins, now high-ranking in IRB, was particularly eager to curb the influence of Griffith’s more moderate polices over the movement.[55]

The numerous convulsions amongst advanced nationalists and radical republicans resulted in the dramatic Sinn Féin Ard Fheis in October 1917. By its conclusion, the sole surviving commandant of the Rising, Eamon de Valera was the new leader of Sinn Féin, with Griffith at Vice-President. And most strikingly, the aim of an Irish republic was now the official goal of the party, however an intriguing clause in the party constitution said it would ultimately be for the Irish public to decide their future form of government after independence.[56]

Thus, an uneasy alliance now emerged in the newly energised Sinn Féin party. As the historian Virginia Glandon wrote of the party in late 1917: “It is apparent that the many elements which compromised the advanced-nationalists’ movement had only pastured over and camouflaged their differences… “[57]

When the differences between these allies ruptured over the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921, once again, Arthur Griffith would be a crucial player at the centre of events.

Conclusion

Robert Brennan, who later worked alongside Griffith in the Dáil, was particularly struck by the latter’s reflection on the 1916 Rising in the years thereafter:

“Griffith could never concede that the Rising of 1916 was the turning point in Irish history. To all of us who had been through the period, there was no question but that the Rising was responsible for changing a people whose sense of national honour had all but vanished… AG could not and would not see that. The change was inevitable, he said. It was bound to come sooner or later. The Rising has hastened it a little. That was all… he had a personal grievance about the Rising…. He was very sore that Sean MacDermott had not trusted him…”[58]

This last point was something that Griffith’s wife, Maud, also noted; the Rising itself the only event in her husband’s political career she wrote at any length on.[59]

Griffith could never concede that the Rising of 1916 was the turning point in Irish history

Griffith’s genuine upset at a close associate like Mac Diarmada for this lack of trust must have a bearing when considering the Sinn Fein founder’s reaction to the 1916 Rising, alongside any of his ideological and pragmatic concerns. Yet, his actions during the rebellion itself were of a convoluted nature, having deeply disapproved of it he initially tried to stop it, then his offer to take part in it was refused, though he then still seemed to seriously contemplate seeking aid for it.

Much is made in historical commentary of how Griffith’s Sinn Féin party grew in popularity of because the Rising. Indeed, the party itself would have gradually faded away had the Rising not occurred, yet as an organized body it provided a viable social and political framework for moderate separatists and radical republicans in which to operate in the months (and years) thereafter.[60]

Given this, Griffith’s own political career was on the ascent in the years thereafter until his death in 1922, having himself previously experienced a period of low standing amongst advanced nationalists prior to the Rising. Thus, while it is unusual to give him a close personal association with the events of Easter Week 1916, it is important to do so when considering the overall historical estimation for a figure of his stature.

Gerard Shannon is a committee member of Skerries Historical Society. In June 2013, he presented his first researched paper before the Society on the death in 1917 of Muriel MacDonagh, wife of the executed 1916 Rising commandant, Thomas MacDonagh. He can be found on Twitter at https://twitter.com/gerry_

References

[1] Sinn Féin Rebellion Handbook, Irish Times, Dublin (1917)

[2] See Laffan, Michael, The Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Féin Party 1916 – 23, Cambridge University Press, New York (2005), pages 69 – 70; Maye, Brian, Arthur Griffith, Griffith College Publications (1997), page 12

[3] Younger, Carlton, Arthur Griffith, Gill and MacMillian Ltd, Dublin (1981), page 50

[4] One such example, see Maye, pages 94 – 111

[5] Laffan, pages 19 – 20

[6] Andrews, C.S., Dublin Made Me, The Lilliput Press Ltd, Dublin (2001 edition), page 1

[7] O’Shiel, Kevin, BMH/WS, page 710

[8] Poblacht na hEireann, 14/08/122, page 1

[9] O’Hegarty, P.S., Classics of Irish History: The Victory of Sinn Féin – How It Won It and How It Used It, University College Press, Dublin (1998 edition), pages 96 – 97

[10] Lyons, George A., Recollections of Griffith and his times, Talbot Press, Dublin (1923), page 74

[11] Lyons, page 76

[12] Maye, page 84

[13] For a take on Griffith’s relationship with the IRB, see Maye, pages 112 – 116

[14] Younger, 38 – 41

[15] Maye, pages 100 – 108; Glandon, Virginia E., Arthur Griffith and the advanced nationalist press: Ireland, 1900-1922 (American University Studies), Peter Lang Gmbh, Internationaler Verlag Der Wissenschaften (1985), page 88

[16] English translation by Donal McCartney in ‘The Making of 1916’ (edited by Kevin Nowlan), page 43, cited on Glandon, page 88

[17] Younger, page 48; see also Brennan, Robert, BMH/WS, page 498

[18] Ó’Briain, Liam, BMH/WS, page 2

[19] Colum, Padraic, Arthur Griffith, Browne and Nolan, Dublin (1959), page 139

[20] Brennan, Robert, BMH/WS, pages 498 – 499

[21] O’ Kelly, Sean T., BMH/WS, pages 231 – 233

[22] O’Briain, Liam, BMH/WS, pages 6 – 7, 10

[23] Lyons, page 75

[24] O’Kelly, Seamus, BMH/WS, pages 5 – 6

[25] Kenny, Joseph, BMH/WS, pages 3 – 5

[26] Griffith, Maud, BMH/WS, page 1 – 2

[27] Griffith, Maud, BMH/WS, page 2

[28] Colum, page 149

[29] Griffith, Maud, BMH/WS, page 1

[30] Hobson, Bulmer, BMH/WS (Subject: The Rising, Easter Week 1916), page 14

[31] O’Briain, Liam, BMH/WS, page 3

[32] Griffith, Maud, BMH/WS, page 1

[33] O’Briain, Liam, BMH/WS, page 3

[34] Colum, page 149; dismissed in Younger, page 56

[35] Michael Noyk quotes this correspondence with O’Briain on this conversation between O’Sullivan and Mac Diarmuida, see Noyk, Michael, BMH/WS, pages 10 – 11

[36] See O’Briain, Liam, BMH/WS, page 3 – 4; and again, O’Briain’s letter to Noyk in Noyk’s witness statement, Noyk, Michael, BMH/WS, pages 10 – 11

[37] Griffith, Maud, BMH/WS, page 2

[38] Colum, page 150

[39] See Griffith, Maud, BMH/WS, pages 1- 2; and Hobson, Bulmer, BMH/WS (Subject: The Rising, Easter Week 1916), page 14

[40] Arthur Griffith Michael Collins, [Commemorative booket], Martin Lester, Dublin (1922), page 53

[41] Brennan, Robert, BMH/WS, page 499.

[42] O’Brian, Liam, BMH/WS, pages 4 – 5

[43] O’Briain, Liam, BMH/WS, pages 5 – 10

[44] Brennan, Robert, BMH/WS, page 499

[45] O’Brolchain, Marie, BMH/WS, pages 2 – 3

[46] Colum, page 151

[47] Griffith, Maud, BMH/WS, page 2

[48] Colum, page 155

[49] Younger, pages 57 – 58, Colum page 151

[50] Hobson, Bulmer, BMH/WS (Subject: The Rising, Easter Week 1916), page 15

[51] Maye, page 117

[52] Nyok, Michael, BMH/WS, page 11

[53] Colum, pages 163 – 64

[54] Maye, pages 121, 130

[55] Maye, pages 125 – 26

[56] Laffan, pages 116 – 121; see also Maye 125 – 130

[57] Glandon, page 202

[58] Brennan, Robert, BMH/WS, page 498

[59] Griffith, Maud, BMH/WS, pages 1 – 2

[60] Maye, page 120