Today in Irish History – August 1, 1915, ‘The fools, the fools’, O’Donovan Rossa’s funeral

An important milestone on the road to the Rising of 1916. By John Dorney.

In August 1915, a volley of rifle shots rang out across a north Dublin graveyard. Mourners at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa – a veteran Fenian bomber of the 1880s – were struck by the militancy of Irish Volunteers – the militia set up in 1913 to ensure the passing of Home Rule and by the fiery rhetoric of one of their leaders, Patrick Pearse.

It was an occasion, carefully staged-managed by the separatist movement, that would strike many as a symbol of their open rejection of the legitimacy of the British state in Ireland. With hindsight, it was also a prelude to the armed insurrection of the following year.

Context

A year before in 1914 Ireland had appeared to be on the verge of civil war. Rival Volunteer movements – Irish and Ulster had sprung up, in the case of the latter to oppose Home Rule or Irish self-government and in the former to make sure it went through. Arms had been imported by the unionists at Larne and by the nationalist at Howth.

John Redmond the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, who at first nervously endorsed the Irish Volunteers, later split the movement by pledging support for Britian in the Great War, which broke out in August of 1914. His followers, the large majority, formed the National Volunteers, many of whom subsequently joined the British Army.

The remainder, keeping the name Irish Volunteers, were heavily infiltrated by the separatist Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). A militant faction within them resolved to launch an armed insurrection against British rule before the War was over.

O’Donovan Rossa was an important Fenian leader in the late 19th century, but his funeral was mainly important as a show of strength by militants among the Irish Volunteer movement.

The O’Donovan Rossa funeral was therefore a chance for the militant minority to make their presence felt in public and to portray themselves as keepers of the militant nationalist tradition.

O’Donovan Rossa himself was almost peripheral to the event, Pearse for one found his methods – he had led a campaign of dynamite attacks in British cities in the 1880s – distasteful.[1] But laying the old Fenian, who had spent most of his post-prison life in the United States, to rest was a great opportunity to stage a show of strength in the Irish capital.

Sean T O’Kelly a leading separatist recalled;

The remains of O’Donovan Rosas were brought to Ireland sometime at the end of July 1915. Previously it had been decided by the I.R.B that a public funeral of the most impressive character should be organised for the burial of O’Donovan Rosas’s remains in Glasnevin Cemetery. I was instructed to select a spot. somewhere near the O’Connell circle in Glasnevin Cemetery and to have grave opened there, the money to be paid for the grave being given to me by Tom Clarke. [2]

Frank Thornton an IRB member and Volunteer remembered that the IRB and its sister organisation in America Clan na Gaedheal did not even want O’Donovan Rossa to touch English soil on his way back to Ireland.

Fifty Volunteers in Liverpool (where his body arrived from New York) carried his coffin on their backs for 2 miles along the docks before he was loaded on a ship to Dublin. At Dublin’s North Wall the coffin was met by another party of Volunteers and taken to City Hall where he lay in state.[3]

The standard narrative of the pre-Rising Irish mood is that the separatists were a tiny minority, disliked by most moderate citizens. And certainly in the insurrection of the following year there is no doubt that the insurgents faced a considerable degree of hostility from the Dublin public. However, this may have been a reaction to the sudden outbreak of violence rather than the politics of the separatists. In August 1915 many participants in the O’Donovan Rossa funeral recalled huge crowds coming out to support it. As Frank Robbin of the Citizen Army put it,

While the remains were in the City Hall there was a continuous stream of Irish men and women, young and old, seeking to pay their last respects to the great old Fenian.[4]

The Day of the Funeral

The funeral itself, the following day was, according to Sean T O’Kelly

‘one of the biggest public funerals that I have ever seen. It was probably the biggest that ever took place in Ireland with the exception possibly of the funeral of Charles Stewart Parnell in October 1891. As well all the branches of the I.R.B. the whole Irish Volunteer organisation was mustered to take part in the funeral and the occasion was used by the Volunteers as an opportunity for showing their strength. As far as I remember the Volunteers marched in uniform, as many of them had uniforms. The funeral procession on that day was certainly most impressive.

As well as the Volunteers public bodies of all kinds sent strong delegations from all parts of Ireland to take part in the funeral. Public bodies like County Councils and Urban Councils Corporations and other bodies of that kind officially took part in the funeral procession. Luckily the weather particularly was kind with the result that many thousands of people stood on the sidewalk to watch the funeral procession pass.[5]

Crowds were huge at the funeral indicating the the separatists did have some public support in the period before the Rising.

Similarly Frank Robbins remembered,

The funeral procession through the city was very impressive. The inspiring message at this funeral was not that we were lamenting the death of O’Donovan Rossa, but that we were celebrating his triumph in the cause of Ireland and honouring this man who was going to his last resting place. The streets of the city along the route of the procession were thronged, and all the way from the starting point at the City Hall until the funeral reached Glasnevin Cemetery, many, many thousands of people paid their last respects to Rossa.

But this was not all public pageant. This was a military display and defiant rejection of the existing state forces in the capital. Volunteer Paul Galligan, an IRB member and by this time adjutant to Volunteer head of training, Thomas MacDonagh, had orders were to keep a clear passage and right-of-way for the Volunteers marching from the city centre to Glasnevin cemetery, from Grattan Bridge over the river Liffey to City Hall. A company of Volunteers were put at his disposal to keep the street clear. ‘A superintendant of the DMP [Dublin Metropolitan Police] approached me in a furious temper”, Galligan recalled.

“He wanted to know under what authority I had stopped the thoroughfare. I informed him I was acting on the orders of my commanding officer.’ The Superintendent accompanied Galligan to see MacDonagh and after an argument, MacDonagh ordered Galligan to put the policeman under arrest. The Volunteers were armed and the Dublin Metropolitan Police were not, so there was little the Superintendant could do about it. The humiliated policeman was detained until after the funeral.

The superintendant was still in Galligan’s custody when the main body of Volunteers marched past in their dark green uniforms, wearing their distinctive Boer-style wide-brimmed hats and carrying rifles and bandoliers of ammunition. When the funeral procession passed, Galligan’s Volunteers formed part of the rearguard and the column proceeded to Glasnevin.[6]

It seems hard to credit at this juncture that the Dublin Metropolitan Police and the British Army stood by and allowed the militant separatists to effectively control the city for an afternoon, but, on the orders of the Chief Secretary Augustine Birrell who considered that more would be lost by heavy handed treatment of Irish nationalists, stand by they did.

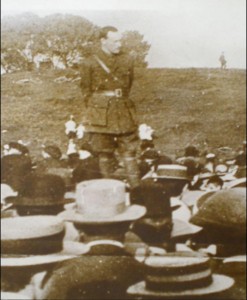

Pearse’s oration

Being towards the rear of the procession, Galligan probably did not hear Patrick Pearse’s graveside oration;

“Life springs from death and from the graves of patriot men and women spring living nations. The Defenders of the Realm have worked well in secrecy and in the open. They think that they have pacified half of us and intimidated the other half…but the fools, the fools, the fools! They have left us our Fenian dead and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.”

‘While Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.” Patrick Pearse at the graveside.

Sean T O‘Kelly records;

Pearse was asked, presumably by [key IRB figure] Tom Clarke to deliver the funeral oration and, as will be remembered, he made one of the great speeches of his life. I very well remember the profound impression that Pearse’s speech made on that day I was standing alongside him when he spoke and we all felt very proud of his impressive oratorical achievement.

He evidently had his speech, which was not too long, well memorised for he used no notes on the occasion. ‘

The oration later became a classic summation of the Republicans’ defiant attitude to British rule. More impressive still, to many onlookers, was the volley of rifle shots that crashed out over the grave when Pearse had finished speaking. A watching priest, Father Curran, thought, “it was more than a farewell to an old Fenian. It was a defiance to England by a new generation in Ireland”.[7]

According to Citizen Army member Frank Robbins, ‘The reaction to all this was a further re-awakening amongst many of the younger generation. It gave a great fillip by way of new recruits into both the Citizen Army and the Irish Volunteers.’[8]

Similarly for O’Kelly,

This must have been one of the first if not the very first occasion on which this military demonstration took place in our lifetime and this too in its way made a deep impression not alone on all who were present but on all who read the report afterwards. The I.R.B. and the Irish Volunteers were very proud of having been able to accomplish this military demonstration despite the orders of the British against the carrying of arms.[9]

These arms would be used for real just eight months later in the Easter Rising of 1916.

References

[1] Pearse said privately he was, ‘a rather unattractive figure’, Fearghal McGarry, The Rising Ireland Easter 1916, 92

[2] Sean T O’Kelly BMH ws 1765

[3] Frank Thorton BMH ws 510

[4] Frank Robbins BMH ws 585

[5] Sean T O’Kelly BMH

[6] Peter Paul Galligan Witness Statement 170, BMH

[7] Fearghal McGarry, The Rising, Ireland Easter 1916. p92.

[8] Robbin BMH

[9] O’Kelly BMH