The Desmond Rebellions Part I, The First Rebellion, 1569-73

The first part of a two part article on the fall of the House of Desmond. BY John Dorney

Not far outside Tralee, in modern day County Kerry, lies a steep valley known as Glanagenty. Near Ballyseedy Cross, after a left turn off the main highway, the road rises steeply into hill country, snaking tightly around corners and through woods until one comes to the valley itself.

The sides of the valley, enclosed by hills on either side, are so steep that one can barely walk up them upright. In the past, a few men posted at either end of the valley could have kept out any attacking force. In the cleft of the valley once stood a Fitzgerald castle.

And it was here in 1583 that Gerald Fitzgerald the last real Earl of Desmond met his death, killed by a local clan, the O’Moriartys, in the pay of the Earl of Ormonde, himself acting on behalf of the English. Desmond was killed in bed and decapitated, his head sent to Queen Elizabeth I and his body displayed triumphantly by the English on the walls of Cork city.

The Desmond Rebellions of 1569-73 and 1579-83 destroyed the Earldom of Desmond and paved the way for the English colonization of Munster.

It was a particularly ignoble fate for the head of the house of Desmond, whose ancestors had ruled much of the south of Ireland for over 300 years. His death marked the end of four brutal years of war and opened the way for the English colonisation of much of southern Ireland in the Munster Plantation.

The south of Ireland lay devastated, with an unknown number, but certainly tens of thousands dead. The Irish Annals of the Four Masters concluded; At this period it was commonly said, that the lowing of a cow, or the whistle of the ploughboy, could scarcely be heard from Dunquinn to Cashel in Munster”.[1] While for the English poet and colonist Edmund Spenser, a most populous and plentiful country was suddenly left void of man or beast”.[2]

What are known as the Desmond Rebellions were two bouts of warfare (1569-73 and 1579-83) as the Elizabethan English state attempted to spread its authority into Munster and collided with the existing power, the Earldom of Desmond, its allies and affiliates.

In equal parts the wars were an aristocratic revolt against central authority, a religious war of Catholic against Protestant and a resistance of various strands of Irish society to the imposition of an alien English social and political order.

Background 16th century Ireland – Conquest or Civil Reformation?

We now speak, with some justification, of the Tudor ‘conquest’ of Ireland but for much of the 16th century the English themselves described it as a ‘civil reformation’ in which law and order would be brought to lawless Ireland.

The Irish lords, both Irish and as in the case of the Fitzgeralds, ‘Old English’ (that is descendants of medieval Anglo-Norman families) would be assimilated into the law governed English state.

The Tudors perceived their political and military intervention into Ireland as a ‘civil reformation’.

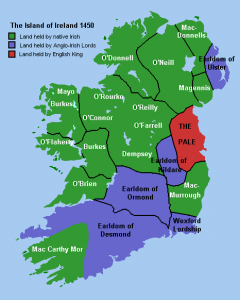

The 16th century had begun with most of Ireland outside of English control, except for Dublin and a small area around it, known as the Pale. Beyond that, at best English presence was maintained by Irish lords of English ancestry such as the Butlers of Ormonde and Fitzgeralds of Kildare and of Desmond.

The conquest had begun with the crushing of a revolt by the Desmond’s cousins, the Fitzgeralds of Kildare in 1534, whose grievance was that their Earl Garret had been stripped of his title of Lord Deputy or governor of Ireland. However at a time when Henry VIII’s break with the Papacy had dangerously isolated England, the Kildare Fitzgerald’s intrigues with continental Catholic powers in France, Spain and Rome were too dangerous for the authorities in London to ignore.

Having put down the Kildare rebellion, in 1542 Henry VIII, determined to expand English control beyond the narrow band around Dublin, had declared the Kingdom of Ireland with himself as King, rather than as, hitherto Lord, of Ireland. He had succeeded in getting most Irish lords to swear allegiance to him via a process known as, ‘Surrender and Regrant’.

This meant that Irish lords would hold their position from now on under English titles such as, for instance, the Earl of Clancarty rather than as clan chieftain MacCarthy Mor. Initially most Gaelic lords were happy to accept Henry’s protection. Enforcing the actual authority of the state across Ireland – especially establishing it as the only body with the right to make war and peace – was another matter entirely

In the case of the Fitzgeralds this initiative made little difference in theory as their presence in Ireland dated back to the Anglo-Norman conquest of the twelfth century and they already held the title of Earls of Desmond. It was only when the English state in Ireland began to truly make itself felt as an armed force in the south of Ireland that problems would arise.

Enforcing the real authority of the English state across Ireland – especially it as the only body with the right to make war and peace – was an extremely difficult task.

Throughout the 1540s and 50s but especially from the 1560s, the English were drawn into bloody little wars in Ulster Leinster and Connacht as they attempted to interfere in internal succession disputes and to enforce their preferred candidates and laterally as they attempted to impose Sheriffs and military governors or ‘Provincial Presidents’.[3]

Annexing one country posed many difficulties but what the English faced in Ireland, in effect was annexing dozens of tiny kingdoms, many of them unstable and wracked by internal feuding. As yet though, before the 1560s this had yet to directly impinge on Munster and the Earldom of Desmond.

Resistance to English authority in Ireland was not only a matter of power and faction however. After Henry’s English Reformation, but especially after the Elizabeth I’s accession to the English throne in 1558, it also assumed a religious dimension. There was no indigenous Protestant tradition in Ireland and those resisting the Crown, for whatever reason, often assumed the position of Catholic Crusaders against heresy.

The Tudor conquest was also to some extent a classic case of colonialism. The English expected that once shown the benefits of the superior English civilization the Irish would simply abandon their own language, customs and laws, in the words of one Palesman, the ‘Civil Reformation’ would ;.

“reduce them [the Irish] from rudeness to knowledge, from treachery to honesty, from savageness to civility, from idleness to labour, from wickedness to Godliness, whereby they may the sooner espy their blindness, acknowledge their looseness, amend their lives, frame themselves pliable to the laws and ordinances of his Majesty whom God with his gracious assistance preserve, as well to the prosperous government of the Realm of England as to the reformation of her realm of Ireland”. [4]

The Ormonde – Desmond rivalry

What set off the Desmond Rebellions, however, by far the worst bloodshed yet seen in 16th century Ireland, was not initially any of these factors but rather competition between the two major powers in the south, the houses of Ormonde and Desmond.

The Earldom of Desmond was a sprawling lordship that stretched from modern day west Waterford through Tipperary right across to modern County Limerick, north Cork and Kerry, with its seat at Newcastle West.The Butlers of Ormonde, their great rivals had their seat at Kilkenny, where their main castle dominated the city, and dominated most what is now County Kilkenny and south Tipperary.

Neither were centralized polities, rather, they were pyramids, by which the ruling lineage collected tribute, both in terms of money and food and also in service, military and otherwise, from a host of vassal lords, who in turn extracted it from their tenants. The economic basis of such lordships was entirely military, it was in other words completely dependent on extraction by armed kin groups of resources from the producers of wealth, farmers and to a smaller degree merchants.

English intervention in a turf war between the Ormonde and Desmond Earldoms eventually led to the Fitzgeralds of Desmond rebelling against English authority.

Economic expansion meant imposing taxation over a wider area. As a result there was constant friction over which lordship would collect taxes from which lord.

A move by the Desmonds to extract tribute from Maurice Fitzgerald, an Ormonde client in the Decies (modern County Waterford) caused the armed forces of the rival Earldoms to meet in battle at Affane in 1565. The Fitzgerald or Geraldine forces were beaten and Gerald the Earl of Desmond was made a prisoner of the Butlers.[5]

One hundred years earlier, the matter might have rested there. Gerald would have been ransomed back to the Desmonds, Maurice Fitzgerald would simply have continued to pay taxes to the Ormonde dynasty and peace would have been restored until the next time one of the lordships tried to chip away at their rival’s territory and income.

This, however was a new era. The rival land and tribute claims of the Desmond and Ormonde Earldoms had been under Crown adjudication. Only the Queen herself had the right to make war within her Realm. So both Earls were summoned first to Waterford city and then to London where they were harshly interrogated about their conduct.

Earl Gerald of Desmond was judged the guilty party in the matter and in 1567 was arrested for treason, held in the Tower of London and forced to pay a huge bond of £20,000 to keep the peace, while ‘Black Tom’ Butler, Earl of Ormonde was allowed to go free. In 1568, Ormonde also managed to pressure Henry Sidney the Lord Deputy to arrest the Earl’s brother and right hand man, John. [6]

The Crown had taken sides in a private war; an action that was bound to cause a reaction.

James Fitzmaurice the ‘Captain General’ of the Desmond military was left in charge of the lordship. By 1569, with the Earl still imprisoned, he was determined to take up arms to reassert Geraldine authority.

Again, in previous times this might simply have been a limited aristocratic revolt that would have ended in compromise and negotiations. A familiar formula, not only in Ireland but across Europe, was one where those in rebellion claimed they were not in revolt against their sovereign (to whom they owed a duty of obedience) but against his or her ‘wicked ministers’. The offending ministers could be dismissed, grievances resolved and peace restored.

However in the context of the English expansion of state power throughout Ireland, with all its dimensions of religious and ethnic conflict and colonial settlement, the first Desmond rebellion took on a far more serious demeanor.

Fitzmaurice presented himself as the representative of the warrior class in Ireland, whose position in society would be made redundant under English rule. He was also a committed Catholic, opposed to innovations in religion and posed also a Gaelic Irish leader, refusing to speak English and dressing in the Irish manner. He himself had lost lands to an English family named St Leger.

That he was joined by several important Gaelic Irish lordships however, was less to do with cultural affinity and more to do with proposed English settlement in Munster, in particular the activities of an English adventurer named Peter Carew, who claimed extensive lands on the southern coast. As result, when Fitzmaurice raised the standard of rebellion, several powerful Irish clans rose up too; notably MacCarthy Mor, O’Sullivan Beare and O’Keefe.[7]

Even some discontented Butlers, threatened by possible loss of lands, initially joined the rebellion, until the Earl of Ormonde, who better understood the gravity of openly defying the Crown, ‘retrieved’ them.

James Fitzmaurice’s Rebellion

The Geraldine and allied forces opened their revolt with an attack on an English settlement at Kerrycurrihy in north Cork, and very quickly expelled the small English garrisons from Desmond territory. Fitzmaurice and his allies, up to 4,500 strong, also briefly laid siege to the Ormonde seat of Kilkenny.

The Geraldine and allied forces opened their revolt with an attack on an English settlement at Kerrycurrihy in north Cork, and very quickly expelled the small English garrisons from Desmond territory. Fitzmaurice and his allies, up to 4,500 strong, also briefly laid siege to the Ormonde seat of Kilkenny.

If Fitzmaurice was expecting his show of force to lead to negotiations, he was wrong. The English state reacted with unprecedented ferocity to the revolt.

Henry Sidney, the Lord Deputy first took the strategic town of Kilmallock whereby he sealed off the rebels in the south. Meanwhile Humphrey Gilbert, an English commander, who the campaign would make notorious in Ireland, laid waste to a wide area, not only taking towns and castles, but also killing any and all civilians he found there.

James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald launched a rebellion in 1569 by attacking an English colony at Kerrycurrihy.

Their heads he cut off and stuck on poles that lined the route into his camps. A contemporary wrote,

The heads of all those (of what sort soever they were) which were killed in the day, should be cut off from their bodies and brought to the place where he encamped at night, and should there be laid on the ground by each side of the way leading into his own tent so that none could come into his tent for any cause but commonly he must pass through a lane of heads which he used ad terrorem…[It brought] great terror to the people when they saw the heads of their dead fathers, brothers, children, kinsfolk, and friends.[8]

‘Of whatever sort they were’. In other words Gilbert killed civilians without care for sex or class. The display of heads was also a particularly shocking act, defiling the body, humiliating the dead and denying them a Christian burial.

It should not be imagined that Ireland had been a peaceful place before the Tudor conquest.

Irish lords were not above killing rivals and displaying their heads as terror tactics, but did not practice wholesale slaughter of non combatants. [9]

English forces and their Irish allies, including the Butlers and their confederates, also systematically destroyed foodstuffs and crops. It was a grim portent of the future

In the months that followed, many of Fitzmaurice’s allies submitted to the English. There followed a long, drawn out guerrilla war until 1573 in which Fitzmaurice’s forces raided towns and settlements from the hills and mountains of north Kerry, though they also managed to defend a number of heavily fortified castles, the most important being at Castlemaine, near Tralee, Geraldine possession of which made it difficult for English force to penetrate into the hilly country to the north and west of the town.

Both sides committed brutal acts but English forces were far more indiscriminate in their attacks on civilians.

In 1571 the rebel forces, having been bolstered by Gallowglass hired fighters of the MacSheehy and MacSweeney clans, sacked Kilmallock. They looted the townspeople, according to the Annals,

to divide among themselves its gold, silver, various riches, [and] valuable jewels and were engaged for the space of three days and nights in carrying away the several kinds of riches and precious goods, as cups and ornamented goblets, upon their horses and steeds, to the woods and forests of Aherlow, and sending others of them privately to their friends and companions.

And they burned the town,

They then set fire to the town, and raised a dense, heavy cloud, and a black, thick, and gloomy shroud of smoke about it, after they had torn down and demolished its houses of stone and wood; so that Kilmallock became the receptacle and abode of wolves.[10]

We should be in no doubt that the sack of Kilmallock (done to deny it as a base to English forces) and other similar events were brutal. But there is a difference between such customary raiding and pillaging and the indiscriminate killing of civilians carried out by Crown forces.

Castlemaine castle finally fell after a protracted siege in late 1572 and the English scorched earth tactics reduced Fitzmaurice’s personal force down to perhaps as few as 100 men. A raid into Connacht in an effort to raise troops among the Burkes came to nothing and a Geraldine foray into Butler country in Kilkenny was bloodily repulsed by Ormonde’s forces.[11]

Fitzmaurice submitted in 1573 but the peace proved only temporary as few of the underlying causes of the rebellion had been resolved.

John Perrot, the Lord President of Munster at one point challenged Fitzmaurice to single combat to settle the war. Fitzmaurice refused but it was the same Perrot who was eventually to take his surrender. In 1573, with Henry Sidney the Lord Deputy removed, James Fitzmaurice submitted toPerrot, who became the new Lord Deputy.

Fitzmaurice, having been offered mercy, submitted at Kilmallock and then fled to Catholic Europe, bringing the first Desmond rebellion to a close. His decision to launch the rebellion may have been unwise and his attacks on English colonists probably helped to provoke the ferocious English response. Nevertheless, his long resilience in the end produced a negotiated settlement.

The leading Fitzgeralds – Gerald the Earl and his brother John, were released from captivity – an implicit acceptance of the part of the Crown that the taking of the Butler’s side in their factional conflict with the Geraldines had been a mistake. It was convenient in the short term to blame James Fitzmaurice alone for the bloodshed of 1569-73

A New Order?

The peace though, as it turned out, proved only temporary. Very few of the underlying causes of the rebellion had been resolved.

The fundamental question was who was really to rule the south of Ireland the Earls with their private armies or the Queen and her officials?

On the ground in Munster, the Lord President, a title which was effectively a military governor, Drury, set about dismantling what he considered to be the objectionable aspects of the old order.

Drury’s policy included executing some 700 Irish soldiers – traditional mercenaries known as Gall Oglaigh or Gallowglass – in the years after the rebellion as a pool of future rebels. [12]

Sir John Perrot the Lord Deputy for his part outlawed the use of Brehon or traditional Irish law, Irish dress, keeping poets as well as maintaining private armies.[13] All of these polices ensured that there was, by the end of the 1570s a large constituency of potential rebels in the south of south of Irleand.

The religious stakes were also raised when the Pope excommunicated Elizabeth I for heresy in 1570. In theory this now meant that her Catholic subjects no longer owed her obedience believed to be due to a lawful monarch.

And in 1579 James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald, now a fully fledged soldier of the counter reformation, returned to Ireland, landing at Smerwick in Kerry with a force of Irish, Italian and Spanish soldiers paid for by Pope Gregory XIII, papal letters and the Catholic Bishop of Dublin, Nicholas Sanders, preaching holy war. It was the start of the Second, far bloodier, Desmond Rebellion.

References

[1] Annals of the Four Masters. Online here.

[2] Spenser A View of the Present State of Ireland. Online here.

[3] Colm Lennon, Sixteenth Century Ireland, the Incomplete Conquest, p179

[4] Richard Stanihurst, Hollished’s Irish Chronicle, p116

[5]Lennon p208-209

[6] Lennon, p 212

[7]Lennon p214

[8] Audrey Horning, Ireland in the Virginian Sea, Colonialism in the British Atlantic p73

[9] See, David Edwards, ‘The Escalation of Violence in sixteenth century Ireland’, in The Age of Atrocity, p47

[10] Annals of the Four Masters

[11] Cyril Falls, Elizabeth’s Irish Wars, p 111

[12] Lennon p 216-218

[13] Ibid.