Cabra in 1916

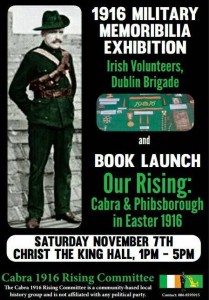

John Dorney on the Launch of ‘Our Rising’ Cabra in 1916′ by Brian Hanley and Donal Fallon. November 7th 2015 at Christ the King Hall, Cabra.

John Dorney on the Launch of ‘Our Rising’ Cabra in 1916′ by Brian Hanley and Donal Fallon. November 7th 2015 at Christ the King Hall, Cabra.

In 1916, Cabra was a mainly rural part of north Dublin, abutting the relatively new suburb of Phibsborough ,itself marked with distinctive red bricked Victorian buildings and crossed with tram lines.

Here in April 1916, about 50 Volunteers from the First Dublin Battalion put up barricades outside St Peter’s Church, to block the progress of British troops into the city from the Navan Road and manned the bridges over the Royal Canal. They had hoped for 150 men to turn up but many stayed at home because of Eoin MacNeill’s countermanding order cancelling ‘maneuvers’ that week.

A few streets away, Bulmer Hobson the leading IRB figure, who had sided with MacNeill, was placed under arrest by several Volunteers sent by Sean McDermott.

Cabra was the first place where British troops used artillery in Dublin in 1916.

When on the Tuesday of Easter Week, British Army reinforcements did arrive in Dublin from Athlone, the rebel outposts at Phibsborough and Cabra were among the first obstacles they had to deal with before they could proceed to the city centre. Their four 18 pounder field guns were first used here, blasting away the insurgents’ barricades. They and the subsequent military sweep of the area killed 9 people, only one of whom was a Volunteer, the others civilians. The troops though were Dubliners too, from the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, who were among the first units mobilised to put down the uprising.

Most of the Volunteers from the area dispersed before the overwhelming firepower of the artillery. Some made their way into the rebel headquarters at the GPO others to Richard Mulcahy’s contingent in Ashbourne County Meath.

All of this the listeners learnt at the launch of ‘Our Rising’ by Brian Hanley and Donal Fallon on November 7th 2015. Both men are historians and both live in modern Cabra. The area has long since changed from the semi-rural suburb it was in 1916. In the 1930s it was covered with row after row of concrete housing estates, an early effort to clear Dublin’s notorious slums.

Today it is a mature area, housing an increasingly eclectic mix of the existing working class community with young professionals attracted by affordable houses prices and rents, and particularity at the Phibsborough end, many immigrants from further afield.

For all that, the area clearly still feels an affection for its history, as the launch was well attended. Diarmuid Breatnach sang songs of the revolutionary period to kick off the event; ‘Sergeant Bailey’ a satirical ballad aimed at British Army recruiters for the great War and ‘James Connolly’ in honour of the executed Citizen Army leader of 1916.

There was also a display of weapons and memorabilia from the era by the Irish Volunteers society.

Brian Hanley said he had been ‘pleasantly surprised’ to find how much Cabra had contributed to the insurrection of 1916. As well as the fighting there, ‘ a key part of British efforts to re-take the north side of the city, many residents in what is now called Dublin 7 played an important part.

Liam Tobin, later one of Michael Collins’ right hand men in IRA Intelligence was living in the area as was Michael O’Hanrahan, who was among the 16 men executed. Jason O’Sullivan a resident of Phibsborough was sentenced to death by General Maxwell, but like 91 others was reprieved after the intervention of Asquith the Prime Minister.

Hanley emphasised the ordinariness of most Volunteers; ‘they were not poets or playwrights or dreamers

Hanley emphasised the ordinariness of most Volunteers; ‘they were not poets or playwrights or dreamers, they did not think they were going out to lose or to sacrifice themselves. When they received mobilisation orders on Easter Monday, they were told they’d win’ he said, in a reference to the idea associated with Patrick Pearse that the Rising was a ‘Blood Sacrifice’.

Hugo McGuinness of the East Wall Historical Society told the story of Catherine Seery, one of those ordinary activists. She and her husband were trade union activists who ‘lost everything’ in the great Lockout of 1913. In 1916 they were both in the Citizen Army ans she ‘baked over 100 loaves of griddle bread’ for the rebel fighters. She later settled in Cabra.

Donal Fallon told the story of Sean T O’Kelly, later a President of Ireland, who cycled around Dublin on the first day of the insurrection pasting up the now famous Proclamation of the Irish Republic. He appealed to the public to remember not only 1916, but also the anti-Conscription protests and the General Election of 1918, the War of Independence and the Civil War that followed it.

Donal Dallon said, Commemoration is too important to be left to the government’. ‘We shouldn’t apologise’ as the struggle for Irish independence was ‘ultimately heroic’.

Commemoration he said, was ‘too important to be left to the government’. In his view, ‘we shouldn’t apologise’ as the struggle for Irish independence was ‘ultimately heroic’.

The book itself is a slim volume but full of interesting information. This writer for instance was not aware that as a result of the extension of the right to vote in 1918 the electorate more than quadrupled from 30,000 to over 120,000 voters. There is also a lot of interesting social and political information about what life was like on the north side of Dublin in the early 1900s.

It also has detailed accounts from participants of the actual combat in and around Cabra in Easter Week. For anyone interested in the Rising, it is well worth picking up a copy.

Some closing remarks; such independent commemoration events for the 2016 centenary are in many ways refreshing as they do not suffer from the heavy weight of caution that hangs on the shoulders of state events. If people think, as many do, that the Irish participation in the First World War was a waste of lives rather than a noble sacrifice they can say so.

One word of caution though. The flip side of self flagellation about the nationalist struggle is self congratulation. I agree with Donal Fallon that we should not apologise for the struggle for Irish independence, but nor should this stop asking the hard questions. Why were so many Dubliners hostile to the insurgents of 1916? Is the Proclamation of the Republic really worthy of the ‘sacred document status’ it now holds? Who hold the responsiblity for the hundreds of non-combatant deaths in Easter week?

That said I fully agree that public engagement with the 1916 centenary and discussion of these seminal events are much preferable to the often stultifying state events.