Today in Irish History – The First Dáil meets and the Soloheadbeg Ambush – 21 January 1919

The declaration of the Irish Republic and first day of the War of Independence. By John Dorney

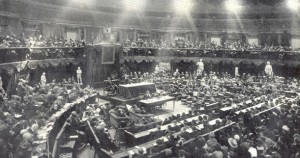

On January 21st 1919, the First Dail or independent Irish Parliament met in Dublin and declared an independent Irish Republic.

As far back as 1905, Arthur Griffith, founder of Sinn Fein, had proposed that Irish separatists should concentrate on winning elections, and then set up their own parliament in Dublin.

Now, in January 1919, after their election triumph in the General Election of December 1918, Griffith’s vision, long thought of as a utopian dream, actually became a reality.

Sinn Fein formed an Irish Parliament – the Dail – which met on January 21st in Dublin’s Mansion House.

‘The Greatest Day’

Out of 73 Sinn Fein members (Teachta Daila or TDs), only 27 were present, 35 deputies were described as being, “imprisoned by the foreigners” (fé ghlas ag Gallaibh). Among them were Eamon de Valera, WT Cosgrave, Arthur Griffith, Terence MacSwiney, Austin Stack, Ernest Blythe and Constance Markievizc, all arrested in the so-called ‘German Plot’ of the previous year.

Another 4 were listed as being, “deported by the foreigners” (ar díbirt ag Gallaibh) in the records of the new parliament. Maire Comerford a young republican activist was present at what she called, ‘the greatest day’. She recalled laughter as Edward Carson – the unionist leader’s name was called. In fact 26 unionist and 6 Irish Parliamentary Party MPs shunned the separatist assembly.

The Dail declared Irish independence and appealed to the ‘free nations of the world’ to recognise it.

The deputies elected Cathal Brugha as their speaker and passed a short ‘Provisional constitution’. They then read the declaration of Irish independence and the ‘message to the free nations of the world’ calling on them to recognise the infant Republic;

The Nation of Ireland having proclaimed her national independence, calls through her elected representatives in Parliament assembled in the Irish Capital on January 21st, 1919, upon every free nation to support the Irish Republic by recognising Ireland’s national status and her right to its vindication at the Peace Congress.

They also read the democratic programme – the social policy document agreed with the Labour Party in return for its not standing in the 1918 election. The programme declared;

It shall be the first duty of the Government of the Republic to make provision for the physical, mental and spiritual well-being of the children, to secure that no child shall suffer hunger or cold from lack of food, clothing, or shelter, but that all shall be provided with the means and facilities requisite for their proper education and training as Citizens of a Free and Gaelic Ireland.

It was heady stuff. Maire Comerford thought there would be no need for further armed resistance. ‘We all thought the case would be taken care of at the Versailles Peace Conference’. She spoke of the ‘joy’ of the TDs, many of them veterans of the failed insurrection of Easter 1916 that ‘the people now loved them’. [1]

The declaration of the Republic was always likely to cause conflict with the British state. Many of the Dail’s leaders were already imprisoned. But did the conflict have to be armed conflict?

Events in County Tipperary on the same day as the Dail’s meeting indicated that it would.

The Soloheadbeg ambush.

The Volunteers in January 1919 administered an oath to their members, in which they swore to be loyal to the Irish Republic and the Dail. Thereafter they were increasingly known as the Irish Republican Army or IRA. [2]

But though Volunteers would come to present themselves as the military arm of the will of the Irish people, the Dail as yet had no direct control over them.

On the same day as the first meeting of the Dail, two RIC policemen were escorting a consignment of gelignite explosives at Soloheadbeg in County Tipperary, when they were ambushed by a party of Volunteers led by Dan Breen, Sean Treacy and Seamus Robinson. The two policemen were shot dead, their weapons and explosives seized.

On the same day, Volunteers shot dead two RIC policemen in Tipperary.

This was far from the first attack on the RIC since the Easter Rising, two Volunteers had died raiding an RIC post in Kerry the previous year and many others had successfully disarmed policemen and taken their guns since then without taking life. [3] No one in the Dail – or even in the Volunteer leadership – had ordered the attack at Soloheadbeg and the Volunteer Chief of Staff Richard Mulcahy even condemned it as murder [4].

Breen later explained his and his comrades’ motives in launching the attack. They as Volunteers were not mere political activists but soldiers of the Irish Republic. ‘We felt there was a grave danger that the Volunteer organisation would degenerate and was degenerating into a purely political body, such as was the AOH [Ancient Orders of Hibernians] or the UIL [United Irish League], and we wished to get it back to its original purpose’.

Dan Breen claimed to have deliberately triggered a war but others thought the raid was imply a botched attempt to capture arms.

They made a decision to shoot the policemen as well as taking their arms; ‘We felt that such a demonstration must have the effect of bringing about similar action in other parts of the country.

The only regret we had, following the ambush, was that there were only two policemen in it instead of the six we expected, because we felt that six dead policemen would have impressed the country wore than a mere two.’[5]

Both at the time and since the Soloheadbeg incident has been used to show that the Volunteers began the subsequent war, that they felt compelled to use force when civil resistance was possible. However in terms of violence, not much differentiated 1919 with its 18 deaths due to political violence, from 1918, which saw a similar number [6].

IRA GHQ and particularly Richard Mulcahy the Volunteer Chief of Staff was most unhappy with the ambush and advised Breen and Treacy to leave the country, though Collins quietly approved of the shootings. However the operation was, as yet, most untypical of Volunteer actions, which generally still consisted of open parades, theft of weapons and bloody, but not generally lethal, riots with the RIC.

Todd Andrews, at that time a very young Volunteer, was highly sceptical of Dan Breen’s claim to have engineered the outbreak of war at Soloheadbeg. He recalled, ‘Breen always claimed that the Solohead shooting was a considered act, taken on his own initiative, to get the guerrilla campaign going but I doubt that very much. I think it was just an operation that went wrong. Elsewhere many RIC were disarmed without being killed.’[7]

The beginning of the War of Independence?

An internal IRA document of November 1921 argued that what it already termed ‘the Irish War of Independence‘ was ‘the logical inevitable struggle to assert the right of a more ancient nation to its own way of life’.[8] In fact though, all out armed conflict was not inevitable in January 1919.

Only 18 people died in political violence in Ireland in that year. The slide into outright war did not begin until early 1920, when IRA GHQ ordered countrywide attacks on RIC barracks. In between came the suppression by the British of the Dail which had first assembled in January 1919.

On March 5th for example, TD for Kerry Piaras Beaslai was arrested for ‘a speech he made at a Robert Emmet commemoration’.[9] On March 29th, the Lieutenant General Shaw, under the Defence of the Realm Act banned ‘all marches and demonstrations’ in Dublin, after Eamon de Valera, recently escaped from prison, announced his plan to make a triumphant entry in to the city.[10]

Soloheadbeg is often cited as the start of the War of Independence but the real escalation in military conflict came in early 1920.

In September 1919, the British banned the Dail, Sinn Fein and a host of other nationalist organizations. Most of the republicans’ political leadership was now in prison. The Irish Times reported on December 20 that military raids had arrested many Sinn Fein leaders including TD Thomas Kelly, Dublin city Alderman and Count Plunkett, father of the executed 1916 leader Joseph Plunkett, who were now held on a warship off Kingstown (now Dun Laoghaire), prior to deportation to Engalnd. The Dail’s office on Harcourt Street was also closed was closed by the military.[11]

Eamon De Valera, the President of the Republic, was by this time in America. Peaceful means appeared to have run into a wall of repression. This left the way open for Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy, who had positioned themselves strategically at the head of both the Volunteers and the IRB, to launch a guerrilla war. Collins had always been convinced that such an eventuality would be necessary. ‘All ordinary peaceful methods are ended and we shall be taking the only alternative actions in a short while now’, he said in late 1919.[12]

So in some ways, Soloheadbeg was a false start. The ensuing guerilla war was a result of subsequent decisions on both sides – of the British authorities to suppress the Dail and of the IRA military leadership to go to war.

Nevertheless, the symbolism of the events of January 21st 1919 was impossible to miss. A rebel Parliament had proclaimed a Republic in Dublin and young men, claiming to be the army of that Republic, had made an apparently pre-meditated and ruthless attack on the existing state’s instrument of coercion.

Ballots and Bullets

January 21st 1919 was a pivotal day in modern Irish history, but its legacy was difficult and complicated. The Dail claimed to represent the will of the Irish people, the Volunteers or IRA were supposed to be their army. But the ambush at Soloheadbeg was not ordered by anyone in the Dail.

January 21st 1919 brings up difficult questions for the role of democracy and militarism within the Irish nationalist revolution.

In fact the Dail did not formally take responsibility for the IRA campaign until March 1921 with a statement from Eamon de Valera to this effect.[13]

So was the Irish nationalist revolution a democratic manifestation of popular will, or an armed struggle led by the vanguard of the IRA? Could the Dail command the IRA or was that organisation responsible only to itself?

These questions stayed dormant during the political and military struggle with the British over the next three years, but erupted with full force with the signing of the Anglo Irish Treaty in December 1922, the Dail’s passing of which led to part of the IRA disavowing the Irish parliament altogether – in turn leading to the Civil War of 1922-23.

In conclusion, what we might remember as Ireland’s independence day turned out to have tortuous and divisive legacies.

See also: Did the ambush at Soloheadbeg being the War of Independence?

References

[1] Maire Comerford papers UCD LA18/15

[2] Witness Statements, Sean Sheridan, Hugh Maguire, Francis Connell, BMH

[3] T Ryle Dwyer, Tans Terror and Troubles, p16

[4] Hopkinson, War of Independence, p115, Richard Mulcahy, head of the Volunteers said it was, “tantamount to murder”.

[5] Daniel Breen BMH 1917-21

[6] Hart, IRA at War, p71

[7] Andrews, Dublin Made Me p119

[8] Mulcahy papers UCD P/7/A/46

[9] Irish Times March 5th 1919

[10] Irish Times March 29th 1919

[11] Irish Times December 20, 1919

[12] Dwyer, Tans, Terror and Troubles, p160

[13] Jason Knirk, Imagining Ireland’s Independence, p62-63