‘The Mad Dance of Death’: The Ulster Protestant Association in Belfast, 1921-22

Loyalist paramilitaries and the birth of the Northern Irish state. By Michael C. Rast

In late 1921, a Belfast police officer came across a secretive loyalist paramilitary organization known as the Ulster Protestant Association or UPA, operating in the city. His investigation uncovers a rarely exposed facet of the Irish revolution.

The Northern authorities’ initial tolerance of the organization and eventual crackdown on it also tells us something about the priorities of the Northern Ireland state at its inception.

Context

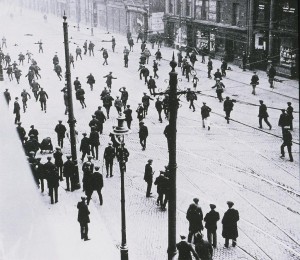

For much of 1921 and 1922, Belfast was in chaos. The city was the capital of the new Northern Ireland, a part of the United Kingdom created from six of the nine counties of the province of Ulster. [1]

Between January and June 1922 alone, 265 people were killed and 555 wounded in Belfast in a three-way war between the Irish Republican Army (IRA), the state security forces comprised of the Army, Royal Ulster Constabulary and Ulster Special Constabulary, and loyalist paramilitaries.[2]

Reporting on the violence in March 1922, the Southern Star said despairingly, “The mad dance of death goes wildly on in the distracted City of Belfast…Human life is reckoned cheap.”[3]

While the conflict was rooted in differences over political ideals, political allegiance throughout Ireland was linked with religious identity.

The Ulster Protestant Association emerged at a time of intense political violence in Belfast.

Catholics usually identified as nationalists or republicans, seeking separation from the British Empire. Protestants were largely unionists, desirous of maintaining Ireland’s place as an integral part of the United Kingdom. While the latter group were a minority across the island, they were the majority in Northern Ireland, comprising 67 percent of the population at the time of partition in 1920.[4]

The nationalist press noted that despite Belfast containing a three-to-one Protestant majority, two-thirds of victims were Catholic. The harshest critics accused Northern Ireland’s government of complicity or at least complacency in the deaths, for instance the Irish Independent asserted, “the party which has assumed responsibility for ‘law and order’ in the North-East is either unable or unwilling to afford a shadow of protection to the Catholic population.”[5]

Northern Ireland’s unionist Premier James Craig occasionally expressed a desire to win over “the better class Roman Catholics in the City.”[6] However he was unequivocal that responsibility for the violence lay solely with the republican movement, which he described collectively as Sinn Féin.[7] He coupled this with a tendency to conflate Sinn Féin with the Catholic population as a whole.[8]

The police commissioner for Northern Ireland, an Englishman named Charles Wickham, was just as explicit. He told a group of police in February 1922, “I expect you know what you are here for—to combat the I.R. [Irish Republic]…we cannot get away from the fact that the I.R. are entirely Roman Catholics.”[9]

Statements like these led some observers, including the nationalist press and Dáil Éireann—the separatist parliament declared in 1919 and governing the 26 counties as a result of the Anglo-Irish Treaty—to allege that the murders were part of an organized campaign to intimidate or extirpate Northern Ireland’s minority population.[10]

A district inspector of the Belfast police thought they were at least partially correct. He believed that many of the killings were the work of a secret loyalist group called the Ulster Protestant Association, or UPA.

District Inspector Reginald Spears

Dublin Protestant Reginald Rowland Spears joined the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) in 1913, receiving top marks on the cadets’ exam in his class.[11] During the First World War he served in the Royal Army Service Corps, returning to the police in 1919.[12]

By 1920 he was a district inspector in Callan, Co. Kilkenny, where Spears came into contact with the IRA, who were becoming increasingly active in the area.[13]

By 1921 he had been transferred to Ballymacarrett in east Belfast, where he again witnessed the violence of the War of Independence. Spears escorted the coffins of two constables killed in the city on the night of January 26. The killings sparked the reprisal murder of reputed Sinn Féin supporter Michael Garvey just hours later.[14]

At the end of June 1921 the Parliament of Northern Ireland opened in Belfast. By the next March the new government was to take control of the police force, drawn largely from the old RIC. Spears was apparently content with the political changes as his name was among the original officers in the new Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC).[15]

Reginald Spears was a Dublin Protestant and RIC and then RUC officer who launched an investigation into the UPA.

He was by no means a dispassionate observer of events in Belfast. Like his superiors, Spears asserted that republicans had started the cycle of assassination and arson consuming the city. In his interpretation, the conflict escalated as, “the rough element on the Protestant side entered thoroughly into the disturbances, met murder with murder, and adopted in many respects the tactics of the rebel gunmen.” The inspector believed the deadliest of the unionist killers in Ballymacarrett belonged to the UPA.[16]

The police knew little about the organization. In a February 1923 report to his superiors, Spears stated that he believed it had originated three years earlier. As IRA activity increased across Ireland in the summer of 1920, Catholic workers were expelled from a number of Belfast businesses as a form of collective punishment for these presumed Sinn Féin sympathizers.[17] By the end of 1921 about 7,410 workers were affected.[18]

In August 1920 a group representing the Ulster Protestant Association, described in the Irish Independent as “A delegation from the shipyards,” visited the Sirocco Engineering Works and encouraged them to keep Catholics from returning to work there.[19] The Sirocco works sat immediately west and the shipyards just north of Ballymacarrett, one of the suspected centers of UPA activity.

Spears thought that the UPA was initially benign, or even potentially beneficial. He described it as, “formed by well-disposed citizens for the protection of Protestants and Loyalists against Sinn Fein aggression.” Branches outside Ballymacarrett included Ormeau, Shankill Road, and York Street. The inspector intimates that the organization was relatively harmless until infiltrated by “the Protestant hooligan element.”[20]

Spears believed that by 1922 the UPA had taken on a different character altogether and were responsible for many of the killings of Catholics in Ballymacarrett, but he had no evidence to prove it. Even when suspected members were arrested, no witnesses would come forward to testify against them. When a member was on trial, one of his comrades would take the stand to provide an alibi. In October 1921 a plumber named Thomas Pentland was arrested for the murder of Catholic Murtagh McStocker.[21] According to the Freeman’s Journal, McStocker was a member of the IRA.[22]

Spears asserted that Pentland was a UPA member and had gunned down McStocker outside St. Matthew’s Church on Bryson Road, a flashpoint in the Ballymacarrett disturbances.[23] Pentland escaped the murder charge.

The informer

In March 1922, the authorities got a break. A disaffected UPA member contacted Northern Ireland’s Home Affairs office conveying information on where some of the organization’s weapons were hidden.

Spears was among a group of constables that raided a stable in Clonallon Street, where they found six rifles, 605 rounds of ammunition, twenty-nine grenades, and a revolver. They arrested three men whose property allowed access to the stable, all of whom were cleared of any wrongdoing at trial.

But Spears did not stop there. Acting on further information, he went to the home of Robert Simpson on nearby Beersbridge Road, and found that he was hiding revolver ammunition.[24] Spears arrested Simpson, who threatened to murder the inspector. From his information and from seized documents Spears ascertained that Simpson was the UPA’s chairman, as well as “its leading desperado and murderer.” Simpson was sentenced to eleven months hard labor, but Spears insisted that he be interned at the end of his sentence.[25] Despite these arrests, no further action was taken against the UPA.

Spears’ main source into the UPA was an informer

One of its members, Joseph Arthurs, was arrested in June for shooting at a British soldier near St. Matthew’s Church.[26] He was later released.

By the end of June 1922 Spears noticed a considerable drop in republican-inspired crime. The Northern government had introduced a series of measures designed to suppress the republican movement.

The Special Powers Act, passed in April, gave Northern Ireland sweeping authority to restore law and order. The act’s vague language could be variably interpreted and selectively enforced.[27] Attorney General Richard Best suggested that punishments under the act might be strengthened, for instance by imposing the death penalty for arms possession “under circumstances which disclosed that they were being carried for evil purposes.”[28] Best did not say what circumstances those were or how they might be ascertained.

The decline of the IRA in the North and the UPA reaction

In May the IRA and other republican organizations were banned; members were subject to indefinite imprisonment without trial, a detention system known as internment. Critics interpreted the law as being aimed at the Catholic community as a whole. 201 suspected republicans were arrested during the first night after internment’s introduction.

Dublin’s nationalist Freeman’s Journal pointed out that they were all Catholics; the London Times insisted that they were IRA officers.[29] In addition to the crackdowns, the Irish Civil War began on June 28 between rival factions of the republican movement, hampering cross-border nationalist cooperation.[30]

After a failed offensive in May 1922, the IRA was crushed in Northern Ireland but loyalist violence continued.

While all of this contributed to curtailing republican outbreaks, attacks on Catholics continued. Spears said that six Catholics were killed in Ballymacarrett between June and October. There were also a number of assaults, shootings, and bombings. The inspector found these acts of violence even more disturbing than the previous outbreaks, as he could not hold republicans responsible for starting the cycle of violence. He refers to the victims as “harmless Catholics” and said they were killed “without any retaliation.”

On October 5, a hidden gunman shot Mary Sherlock across the street from St. Matthew’s Church.[31] The authorities reacted more strenuously to this killing than to many of those that had preceded it. They immediately offered a £2,000 reward for information leading to the capture of Sherlock’s killers. At the inquest Philip Bell, representing the victim’s family, said, “the event was most distressing in view of the fact that the public mind had anticipated the establishment of peace in the city.”[32] The same night Mary Sherlock was killed, Spears arrested Joseph Arthurs and Frederick Pollock, two local UPA members he suspected of the crime.

Soon after the Sherlock murder, a UPA member visited Spears and told the inspector his comrades had mistreated him. The unidentified man also claimed to want the killing to stop and gave up the locations of three UPA arms dumps. Spears sent search parties to all three. At 20 Solway Street the inspector found signs that weapons had recently been removed. The other two locations—a yard in Susan Street and McCalmont’s Felt Works in Pitt Street—yielded seventeen grenades, two rifles, and 2,100 rounds of ammunition.[33]

Spears set up regular meetings with his informant, and began to learn the inner workings of the UPA. The organization had about 150 members, approximately one third of whom were active gunmen. In Spears’s words, “the whole aim and object of the club was simply the extermination of Catholics by any and every means.”

‘Thoroughly disorganised’ – The end of the UPA

After Spears put away Robert Simpson, Robert Craig had taken over as chairman. Thomas Pentland acted as his lieutenant.

The Ballymacarrett UPA met every Thursday in an upper room of Hasting’s pub on Newtownards Road, near Scotch Row. Pentland introduced corporal punishment to the organization; members could be beaten with a cat-o-nine-tails or whipped on a flogging horse for breaking its rules.

This was not entirely novel for Northern Ireland as the government had introduced flogging as a method of punishment under the Special Powers Act.

Spears staked out the association’s headquarters on Thursday nights. The second week of this operation, a Constable Harrison was standing watch outside Hasting’s when a group of young men left the pub and walked right up to him. One drew a revolver and told him to put his hands up. Instead the policeman drew his own weapon and the group scattered.

Spears raided the pub the next Thursday, but Craig had warned all the members not to come armed, and the inspector had no reason to hold them. However he did capture all of the organization’s papers. They found two different oaths required to join the association. The first was “comparatively harmless,” the second “was practically a vow to murder.” It is possible that the existence of two oaths was a relic of the UPA’s transition from a partisan but law-abiding organization to one dedicated to killing.

The RUC investigation into the UPA found it was engaged in extortion and beatings as well as sectarian murder.

The UPA obtained funds by extorting local business-owners in Ballymacarrett. They used the money to buy weapons and pay a solicitor, Nathanial Tughan, to defend its members after arrest. After the raid two UPA members, William J. Morrow and Archibald Pollock, escaped the RUC by going to Britain and joining the Army. Next Spears obtained an internment order for four of the UPA’s leading lights: Robert Craig, Thomas Pentland, George Gray, and Robert Waddell. He arrested them all on November 5.

However, the shootings and bombings continued until Spears arrested two more members, John Darley and Frederick Brereton. The inspector said that the UPA was now “thoroughly disorganised,” and learned through his informant that they were taking steps to hide their weapons. So, Spears set up a sting operation.

The inspector was lying in wait at the Oval football grounds on the night of November 20 with a head constable and three subordinates when a group of men arrived and began digging under one of the grandstands. By a series of signals involving lighted matches, Spears’s informant let the constables know the right time to pounce. Thomas Waring, George Richards, and the informant were caught with three rifles, eight grenades, and 292 rounds of ammunition.[34]

As the prisoners were being escorted to Strandtown police barracks, Spears’s informant made an opportune—and prearranged—escape. Thomas Waring and George Richards were each sentenced to a year’s imprisonment for being caught with the weapons at the Oval football grounds.[35]

By February 1923 Spears declared to his superiors, “The men chiefly and directly responsible for the whole disorder on the Protestant side in this district are now rendered incapable of doing harm, and whilst they continue to be so incapacitated I see no reason to apprehend further outbreaks of trouble from that section of the population.” He added that outside of the families of the arrested men, “the general public regards it with much gratification.”

This is where Spears’s narrative of his investigation into the UPA ends. It seems to provide an exciting story of a fearless policeman going up against ruthless lawbreakers and bringing them to heel, to the benefit of frightened locals, including a harried religious minority population. It would seem to vindicate the power and determination of the state to protect all of its citizens.

The UPA’s ties to the Northern Ireland government

However, there were a number of things about the operation that never came to public notice, particularly the UPA’s ties to Northern Ireland’s government. Some of them were members of the C-class Special Constabulary.[36]

Northern Ireland’s Prime Minister James Craig had suggested arming these part-time police for “self protection,” but there was no general distribution of weapons.[37]

At least one of the UPA leaders, Robert Craig, was a paid agent of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), the state’s secret service organization that reported directly to Major-General Arthur Solly Flood, military adviser to Northern Ireland’s government. He said that he got the job through R. Dawson Bates, the Minister of Home Affairs, and worked for the CID until September 1922, well into the UPA’s rampage in Ballymacarrett.

At least one of the UPA leaders, Robert Craig, was a paid agent of the RUC Criminal Investigation Department (CID), the state’s secret service organization.

Robert Craig was also a former member of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), an anti-Home Rule militia set up before the First World War by James Craig and Edward Carson. By 1922 his brother was one of the C-Specials guarding the UVF armory in Tamar Street, which might explain where some of the UPA’s extensive arsenal originated.[38]

The organization felt that they could exercise considerable influence with Northern Ireland’s government. After Spears arrested UPA leader Robert Simpson, Robert Craig wrote a letter to Bates demanding his release. Barring this, the organization’s four branches would march to the Northern Ireland Parliament building, headed by two bands, and demand Simpson’s freedom.

Craig wrote, “I am not writing this as a threat,” which of course he was, but that he might not be able to control the “hot heads of our Association.”[39] Bates’s Home Affairs office was alarmed enough to alert the RUC of the threat and ask them to take measures to “prevent disorder.”[40] Thus, as early as July 1922, Northern Ireland’s government perceived the UPA to be a threat.

All of the organization’s members were unequivocal that they were working, if not directly for, then in the interests of Northern Ireland’s government. UPA member Frederick Brereton claimed that they had helped the unionist party during the first six-county election in May 1921. He specifically mentioned working with Bates.[41]

Bates was then secretary to the Ulster Unionist Council (UUC) and coordinated most of its activities, therefore it is plausible that he kept in touch with local organizations acting on behalf of his party. Other members claimed that they aided the police in Ballymacarrett by forcing looters to give up their spoils and turning them over to the authorities.[42] This was simply a tactic to try and obtain release from internment, but this was just one way in which UPA members insisted that they were acting on behalf of larger forces. Robert Simpson told prison authorities, “I, sir, may have broken the law but it was to assist the Crown Forces in my own way.” He listed his Protestant and unionist credentials and added, “it is hardly likely that I am about to wreck that which I fought for.”[43]

The extent to which Spears was aware of the UPA’s relationship with the government is unclear. However he seems to have had a greater knowledge of the organization than his report indicates. After Sherlock’s murder Spears knew exactly who to arrest and where to locate them, but does not say where he obtained this information.

The inspector also does not say why his UPA informant approached him specifically and, apparently, unsolicited. It is possible that Spears, as the ranking police officer in Ballymacarrett, was the obvious authority to approach. It is also possible that the informant was steered to Spears by officials higher up in Northern Ireland’s government eager to rid themselves of their troublesome UPA adjunct.

On at least one occasion the inspector made arrests on the direct orders of Bates and Police Commissioner Wickham, namely the apprehensions of Frederick Brereton and John Darley.[44] The Dublin-born Spears, lacking any local connections, was the perfect officer to suppress the UPA without compunction or fear of reprisal.

Whatever Spears knew about the UPA during its rampage through his district, his role in its suppression provided a boost to his career. King George V knighted him in June 1923. Eight years later he was promoted to RUC County Inspector.[45]

On October 9, 1922, Bates informed a cabinet meeting of “certain information that had been received about disorderly Protestant organizations.”[46] He also kept Prime Minister James Craig informed of the progress of the investigation.[47] In September 1923 the press reported that the constabulary were investigating the UPA, Protestant Voters’ Association, and Ulster Reform Association.[48]

There is no evidence that the latter two were engaged in criminality, though they were opposed to the “official unionists,” Northern Ireland’s sitting government.[49] Moreover, this announcement came months after Spears claimed police had dismantled the UPA in its Ballymacarrett stronghold. These operations appear to be the actions of a government more concerned with safeguarding its authority than with upholding law and order.

Aftermath

Some of the UPA members Spears had arrested did not fare too badly in the long run. Immediately after their internment their relatives, trades unions, and even politicians began to appeal for their release. William Grant, an MP for Belfast North, even paid the rent for UPA member George Gray’s family for three months.[50] By March 1924 they had all been released from prison. The police record of Joseph Arthurs, originally arrested for the murder of Mary Sherlock, notes that he was released, “on the request of his friends.”[51]

There is significant evidence that members of that government enlisted UPA members into their service, and only disowned and suppressed them when they were no longer needed.

The Northern Ireland government view of the UPA transformed rapidly. During the civil disturbances up to July 1922, it was seen as necessary to help suppress republicans. However, its unpredictability and popular support made it dangerous. Once the republican movement in Northern Ireland had been suppressed and relative peace established, the circumstances that were seen as driving its members to violence were no longer pertinent, therefore they could safely be released.

The case of a UPA member who did not feature in Spears’s report illustrates this process. In October 1922, an RUC sergeant arrested Alexander “Buck Alec” Robinson, whom he called “one of the most notorious gunmen and murderers in the City of Belfast.”[52]

Also a C-Special, Robinson was suspected of at least three murders and throwing a grenade into a crowded tramcar. His police file claims that he “actually takes a delight in killing.”[53] Despite all of this, in July 1923 the same RUC officer quoted above recommended that he be released. The sergeant stated that, “the conditions which necessitated Robinson’s internment in the first instance are no longer operative,” and he was “sure that this man has had a useful lesson.”[54]

Conclusion

Policing in Northern Ireland is often viewed as a Protestant and unionist state exerting its influence to suppress a Catholic and nationalist minority population.[55] Examining the UPA affair through Spears’s 1923 report might force an examination of this narrative, but a broader investigation shows that this reexamination can only be a limited one.

The Protestant Inspector Spears is potentially a disinterested protector of all citizens, though this effect is lessened by his casting blame for all of the disorder in Belfast on republicans. In this respect he conformed to the opinions of his superiors in Northern Ireland’s government.

The fact that a Protestant and unionist administration suppressed an organization of similar religious and political composition is potentially edifying. However there is significant evidence that members of that government were enlisting UPA members into their service, and only disowned and suppressed them when they were no longer needed and in fact had become a political threat within unionism.

The fact that Northern Ireland’s government was willing to use the UPA to aid its official forces in suppressing republicanism shows the ruthless methods they were willing to condone against opponents outside of their political and religious community. They were less brutal in suppressing the UPA, but doing so enabled them to consolidate power within the Protestant and unionist ranks.

Michael C Rast is a Phd student at the Concordia University Montreal.

References

[1] Times (London), 23 June 1921; Morning Post (London), reprinted in the Belfast News-Letter, 23 June 1921.

[2] Irish Independent (Dublin), 17 July 1922.

[3] Southern Star (Skibbereen), 25 March 1922.

[4] P. A. Compton, “Religious affiliation and demographic variability in Northern Ireland,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 1, no. 4 (1976): 436.

[5] Irish Independent (Dublin), 27 March 1922.

[6] Public Record Office Northern Ireland (PRONI), CAB/6/81, James Craig to Hamar Greenwood, 6 October 1921.

[7] PRONI, CAB/6/77, James Craig to FitzAlan, 7 January 1922.

[8] PRONI, CAB/6/77, James Craig to FitzAlan, 28 December 1921.

[9] Irish Independent (Dublin), 27 February 1922.

[10] Freeman’s Journal (Dublin), 20 February 1922; Freeman’s Journal (Dublin) 6 June 1922.

[11] PRONI, MIC 454/13; Connacht Tribune (Galway), 29 November 1913.

[12] London Gazette, 15 October 1915; Jim Herlihy, The Royal Irish Constabulary: A Short History and Genealogical Guide (Dublin: Four Courts: 1997), 225.

[13] Thomas Treacy, Bureau of Military History (BMH) Witness Statement (WS) No. 1,093, 47.

[14] Times (London), 28 January 1921; Irish Independent (Dublin), 31 January 1921.

[15] Belfast Gazette, 15 September 1922.

[16] PRONI, CAB/6/92, R. R. Spears, “Report on the Ulster Protestant Association,” 7 February 1923.

[17] Times (London), 29 July 1920.

[18] Irish Military Archives, BMH CD45 Group 11 Subject No. 7, “Approximate Number of Workers Expelled.”

[19] Irish Independent (Dublin), 11 August 1920.

[20] PRONI, CAB/6/92, Spears, “Report on the Ulster Protestant Association.”

[21] Irish Independent (Dublin), 29 October 1921.

[22] Freeman’s Journal (Dublin), 7 October 1921.

[23] PRONI, CAB/6/92, Spears, “Report on the Ulster Protestant Association.”

[24] Ulster Herald (Omagh), 1 April 1922.

[25] PRONI, CAB/6/92, Spears, “Report on the Ulster Protestant Association.”

[26] Freeman’s Journal (Dublin), 6 June 1922.

[27] Laura K. Donohue, “Regulating Northern Ireland: The Special Powers Acts, 1922-1972,” The Historical Journal 41, no. 4 (1998): 1090-1091, 1093-1095.

[28] Ulster Herald (Omagh), 1 April 1922.

[29] Freeman’s Journal (Dublin), 24 May 1922; Times (London), 24 May 1922.

[30] Belfast News-Letter, 18 July 1922; PRONI, CAB/8/G/1, Arthur Solly Flood to W. B. Spender, 3 October 1922.

[31] Freeman’s Journal (Dublin), 6 October 1922.

[32] Belfast News-Letter, 6 October 1922 and 7 October 1922.

[33] Belfast News-Letter, 9 October 1922.

[34] Ulster Herald (Omagh), 25 November 1922; Irish Independent (Dublin), 29 November 1922.

[35] Freeman’s Journal (Dublin), 26 February 1923.

[36] PRONI, HA/5/2193, Archibald Pollock to S. Watt, 6 November 1922; PRONI, HA/5/2192/47, Alexander Robinson, Petition, 23 October 1922.

[37] PRONI, CAB/6/27A, W. B. Spender to C. G. Wickham, 28 October 1921.

[38] PRONI, HA/5/2223, R. R. Spears, “List of persons recommended for internment;” PRONI, HA/5/2223, Robert Craig, “Representations against Internment Order.”

[39] PRONI, HA/5/962B, Robert Craig to R. Dawson Bates, 10 July 1922.

[40] PRONI, HA/5/962B, A. P. Magill to J. F. Gelston, 13 July 1922.

[41] PRONI, HA/5/2248, Frederick Brereton, “Questions of the Advisory Committee.”

[42] PRONI, HA/5/2223, Robert Craig, “Questions of the Advisory Committee;” PRONI, HA/5/2221, Thomas Pentland, “Questions of the Advisory Committee;” PRONI, HA/5/2220, Robert Waddell, “Questions of the Advisory Committee.”

[43] PRONI, HA/5/962B, Robert Simpson, “Representations against Internment Order.”

[44] PRONI, HA/5/2248, R. R. Spears, Report, 16 November 1922.

[45] Times (London), 30 June 1923; Belfast Gazette, 13 March 1931.

[46] PRONI, CAB/4/55/12, Cabinet Minutes, 9 October 1922.

[47] PRONI, HA/5/1482, R. Dawson Bates to W. B. Spender, 21 November 1922.

[48] Irish Independent (Dublin), 8 September 1922.

[49] For the Ulster Protestant Voters’ Association see PRONI, HA/32/1/296, J. Wilkin, Report, 7 October 1922; For the Ulster Reform Association see PRONI, CAB/9B/33/3, E. Gilfillan to S. Watt, 20 July 1923.

[50] PRONI, HA/5/2222, Annie Armstrong to H. Toppin, 24 April 1923.

[51] PRONI, HA/5/693, “Protestants Who Have Been Interned.”

[52] PRONI, HA/5/2192/26, C. O’Beirne, Report, 21 October 1922.

[53] PRONI, HA/5/2192/45, “Persons Recommended for Internment.”

[54] PRONI, HA/5/2192/46, C. O’Beirne, Report, 20 July 1923.

[55] Eamon Phoenix, Northern Nationalism: Nationalist Politics, Partition and the Catholic Minority in Northern Ireland, 1890-1940 (Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation, 1994), 242-243. For this view and a rebuttal see Patrick Buckland, “A Protestant State: Unionists in Government, 1921-39,” in Defenders of the Union: A Survey of British and Irish Unionism Since 1801, eds. D. George Boyce and Alan O’Day (London: Routledge, 2001), 211-215.