Book Review: One Bold Deed of Open Treason: The Berlin Diary of Roger Casement 1914-1916

Edited by Angus Mitchell

Edited by Angus Mitchell

Published by Merrion Press, 2016,

Reviewer: Daniel Murray

In February 1916, Roger Casement was recovering near Munich from an unpleasant combination of tropical fever and nervous exhaustion when he replied to a letter from the Countess Blücher, asking for help with writing tips for her diary. Eager to help, Casement expounded at length on the delights – and dangers – of keeping a journal:

You know the charm of a diary is its simplicity. Its reality and the sense of daily life it conveys to the reader depends not on style, but on truth and sincerity. It should tell things but still more of the writer and his (or her) outlook on those things.

Casement was conscious of his role in history, taking meticulous care that his personal papers be suitably prepared and leaving behind detailed instructions for their dispersal and eventual publication

Sometimes a diary could tell too much. Casement confessed to the Countess that he had given up on the one he had been writing while in Germany as he found himself recording things that were best left in the dark.

As indicated, keeping a diary was no simple matter but then, there was little in Casement’s life, not least his time in Germany, that was simple. As he confessed at the start of another diary of his, recently reprinted here: “It is not every day that even an Irishman commits High Treason especially one who has been in the service of the Sovereign he discards.”

Quite.

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a man whose earlier claim to fame had been his exposé of human rights abuses – first in the Congo and later Peru – Casement was conscious of his role in history, taking meticulous care that his personal papers be suitably prepared and leaving behind detailed instructions for their dispersal and eventual publication.

With an eye to posterity – and a trace of grandiosity – he explained the value of his documents to his friends: “they are historic & I leave them to Ireland.”

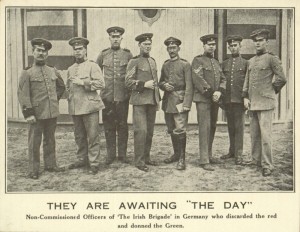

This forward thinking and the wealth of information it ensured are in no small part the reason why Casement has been one of the better remembered figures of 1916, despite his role being a sideshow to the Rising and not a terribly successful one by anyone’s yardstick: his mission to raise a regiment amongst Irish prisoners in German POW camps resulted in only a handful of recruits and the withdrawal of interest on the part of the German authorities.

This book is well served by its editor. Historian Angus Mitchell adroitly guides the reader through the literary and historical context.

The disillusionment was mutual. “My last day in Berlin!” he wrote in this diary’s last entry for the 11th April 1916 as he departed for Ireland and the fate he was at least half-expecting to find: “Thank God – tomorrow my last day in Germany – again thank God, an English jail, or scaffold, would be better than to dwell with these people longer. All deception – all self-interest.”

This book is well served by its editor. Historian Angus Mitchell adroitly guides the reader through the literary and historical context in which Casement composed this diary, and his introduction should be highly informative to those who know only of Casement’s diaries of the Black sort (Mitchell leaves his thoughts on the authenticity of that divisive matter unstated).

But the star of the show is undoubtedly Casement, always an engaging writer keen to leave an impression on his reader as evidenced by the artful descriptions – the Irish-American liftboys in New York had “the brogue still lingering round the shores of that broad estuary of smiles that takes the place of a mouth in the true Milesian face” – or his crisp accounts of his increasingly acrimonious relationships with various German officials.

Much of the later book makes for painful reading as Casement slowly realises the lack of concern his allies truly had for Ireland.

Much of the later book makes for painful reading as Casement slowly realises the lack of concern his allies truly had for Ireland except as a convenient second front against Britain.

Which should have been obvious from the start – after all, nations have no friends, only interests, and Casement was too experienced a diplomat not to know this – but the picture that emerges from these pages is of a rather fey individual, intelligent enough to recognise the scale of his plight but not self-aware enough to see how he got there in the first place. But at least he had the comfort of knowing that it was all someone else’s fault anyway.

Still, regardless of one’s thoughts about Casement – and he will continue to be debated – those wanting to learn more about one of the most iconic and controversial figures in 20th century Irish history would be well advised to start here with the subject’s own thoughts and feelings.