Policing Revolutionary Dublin 1919-1923

Crime and punishment during nationalist revolution in Dublin. By John Dorney

The most obvious way the state enters our lives is when it attempts to enforce its laws and punish those who break them. For this, as Frederick Engels once wrote it needs ‘bodies of armed men’.[1] In the final instance these may be soldiers, but most of the time they are police, charged specifically with upholding the law.

In any revolutionary situation, the first thing those trying to pull down the existing state must do is to attack and disable the existing police force. In the Irish nationalist revolution of 1919-23, this certainly occurred. The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) were made the subject of concerted armed campaign and their authority was either replaced by Republican courts or police or reduced to brute, quasi-military force.

Dublin was a little unusual in that its police force, the Dublin Metropolitan Police, or DMP, was unlike the RIC, unarmed. Also unlike the RIC, the DMP survived the revolutionary years without disbandment and was integrated into the new national police force, the Garda Siochana in 1925.

However, underneath this apparently smooth transition lies a story of revolutionary turmoil, the effective collapse of the police in the Irish capital, an explosion in ordinary crime and the re-imposition of order under the Irish Free State after 1923.

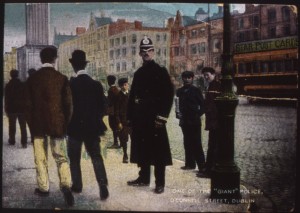

The DMP – policing Dublin

The DMP was founded by an Act of the Westminster Parliament, the Dublin Police Act of 1836, replacing the old haphazard system of night-watchmen, constables and horse patrol – bodies that had accumulated since the late 18th century.[2]

The new, unarmed force had a strength of about 800 initially but by the early twentieth century was up to over 1,100 men, grouped into six geographical Divisions; four in the city, D and C north of the river Liffey and A and B on the south side, E in the southern suburbs and F in the south county, plus a Detective squad, G Division, which was raised in 1843.

The G Division was about 50 men strong by the outbreak of revolutionary strife in 1916 and was based in Dublin Castle and in offices on Exchange Street.[3]

The Dublin Metropolitan police was 1,100 strong in 1916, making Dublin one of the most heavily policed cities in the United Kingdom.

G Division was charged with investigating all unsolved crimes but it was also given primary responsibility for investigating and infiltrating radical nationalist organisations such as the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

By 1900, Dublin, with a population of 390,000, was per head of population the most heavily policed city in the United Kingdom, with one policeman for every 330 people, compared with one for roughly 500 in British cities. It was a city of extremes, containing great wealth and abject poverty and perhaps as a result had over twice the crime rate of Belfast or Cork and greater also than most British cities.

Despite this, it was not, until the advent of violent political unrest, a particularly dangerous place. In the early 1900s about 80% of the 3,000 or so offences recorded every year were comprised of non-violent theft and most of the rest were connected with drunkenness and assault, with usually only about two to three murders a year.[4]

The DMP were brought into some disrepute by their heavy handed treatment of strikers in the great strike or Lockout of 1913 – beating to death a least three strikers during the dispute and injuring many hundreds more. It came under further pressure during the Howth gun running of 1914, when many constables refused to obey orders to disarm the Irish Volunteers who had illegally imported German rifles at Howth. The DMP also went on strike in 1916 for better pay to cover wartime inflation and for freedom to join Catholic societies such as the Ancient Order of Hibernians.

However, it was the appearance of major political violence after the Rising of 1916 and especially after Sinn Fein tried to seize the reins of state power after their victory in the General Election of 1918 and the local elections of 1920 (they took over Dublin Corporation in in alliance with Labour in January of that year) that brought about a situation of ‘dual power’ in the city, rendering the old means of enforcing the law irrelevant.

The Counter State

In January 1919, the Sinn Fein MPs met in Dublin and declared an Irish Republic. All over Ireland in 1919 and 1920 the newly ascendant Sinn Fein took over the functions of the state where they could. In January 1919 a boycott was placed on the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and on the existing courts. This was extended to the DMP in mid-1919.[5]

The existing courts system was replaced in many parts of Ireland by the Dail (also called Sinn Fein) Courts and the RIC by either the Irish Republican Army (IRA) or a related body named the Irish Republican Police (IRP). By mid-1920, along with the elected Sinn Fein local governments, they had effectively hollowed out the British administration.

Sinn Fein declared an Irish Republic in 1919 and proceeded to create parallel Republican police and Courts system.

The first republican courts were National Arbitration Courts, which were legal, voluntary bodies that handled civil cases. However, the law and order situation deteriorated as the political violence worsened and the RIC withdrew from the countryside in early 1920, forcing the republicans to take over more state functions. In June 1920 Republican Courts or Dail Courts were launched to replace completely the existing Justice system.[6]

The republican counter state – collecting its own taxes and enforcing its own law – popped up not only in remote rural regions but in the centre of the British administration in Dublin.

Taxes were withheld from the state and paid instead to the Republican authorities where possible. Indeed in Dublin IRA Companies were instructed in mid 1920 to raid the homes of rate (local tax) collectors and force them to sign over their takings to the Republic [7]. Various means were also used to levy a kind of war tax on the population.

Having won control of the Dublin Corporation in 1920 they now had its rates under their control until the British government froze all funds of local government bodies under Sinn Fein control. In a raid by the British Army in December 1920, City Hall was turned into a military base, it funds impounded and several councillors imprisoned.[8]

There was also a ‘Republican gold reserve’ of £25,000 and another £325,000 collected in the ‘National Land Bank’[9] The Republic therefore was not without funds, which it mainly spent on arms, ammunition and paying its few fulltime fighters and administrators.

Destroying the old system

Twelve DMP officers lost their lives during the War of Independence in Dublin from 1919-1921, out of a total of about 300 people killed in Dublin. All but one of these were G Division detectives killed in the assault by Michael Collins’ IRA Squad on the DMP’s intelligence arm from July 1919 to April 1920.[10]

This assassination campaign effectively disabled the force as a real asset to the British authorities. In fact a number of important G Division detectives such as Eamon Broy and David Nelligan actually secretly defected and worked for Collins and IRA Intelligence; in Broy’s case up to his arrest, in Nelligan’s case remaining undiscovered throughout the period.

Ordinary DMP constables were at first armed and sent to accompany British Army patrols in Dublin to seek out IRA suspects. But most were extremely unenthusiastic about the work and the military soon complained of carrying ‘passengers’. In October 1920, representatives of the DMP clandestinely worked out a deal with Michael Collins whereby IRA attacks on the Dublin police would stop if they ceased carrying arms. After talks between the policemen and Jeremiah Mee, a defector from the RIC who spoke on Collins’ behalf, a deal was reached and the DMP stepped out of the war.[11]

Michael Collins’s Squad destroyed the G Division of the DMP, but most of the force refused to take part in counter insurgency operations.

The unintended effect of this neutering of the police force was that during the War of Independence and the subsequent Truce period in Dublin, ‘ordinary’ crime sky-rocketed alongside political violence. The proliferation of lethal weapons on the street and the often lax discipline of both British and Republican forces made the normal policing methods of the (now again unarmed) DMP redundant.

There was a massive British security presence in the city in the form of the British Army and Auxiliaries, but almost all their efforts went into containing the Republican insurgency. As a result, a considerable portion of the Republicans’ efforts in Dublin were put into trying to replace the old policing and justice systems that they had effectively undermined.

Republican justice

The Republicans in Dublin detailed a fulltime squad of 12 men of the Irish Republican Police (paid at the same rate as their fulltime guerrillas in the Squad and Active Service Unit), led by an apprentice carpenter named Sean Condron to fight ordinary crime in 1920-21.

They also set up at least two clandestine Dail Courts, in Pembroke and Rathmines, staffed by four Justices each, one of whom had to be a woman and one a priest.

According to Maire Comerford, a Cumann na mBan Republican activist, the Pembroke Ward Court was held in Aine Heron’s house in the salubrious suburb of Ballsbridge and there were some attempts at enforcing a vision of social justice. A money lender, for instance who had charged interest of 800% was ordered not to be repaid. On that occasion though the Republican Minister for Home Affairs, Austin Stack (who operated out of an underground office on Henry Street) stepped in to reverse the decision.

Two Dail Courts and a fulltime unit of Irish Republican Police operated in Dublin during the War of Independence.

Sean Condron’s men, the Republican Police, who were charged with enforcing the Courts’ rulings, were actually disappointed they had been given a non-combat role and by his own admission, ‘had no idea how to investigate crime’. They held up ‘gangsters’ at gunpoint and at one point had ten men (‘ugly customers’ according to Condron) locked in a shed in the Ringsend area.

Those convicted in the Dail Courts were sentenced to exile from Ireland, as there was nowhere secure to hold them. After the Truce, when the IRP could operate a little more openly, they handed over prisoners to Mountjoy Gaol, including three Royal Air Force officers who had robbed a building site.[12]

The IRP was always shorthanded and underfunded and maintained only a small office on Eustace Street in Temple Bar. Thus the ‘regular’ IRA battalions were also pressed into a kind of policing role, particularly after the Truce that ended open hostilities with the British on July 11, 1921.

Joe O’Connor’s Third Battalion of the IRA Dublin Brigade, based in the south inner city, was one such unit. With the DMP in O’Connor’s words, ‘practically inoperative, there was a danger the criminal element would take advantage.’ He recalled a ‘particularly bad gang’ had robbed an old man and kicked him into the Grand Canal. O’Connor had them arrested at gunpoint and ‘their leader Hatchet O’Connor, was deported for ten years’.[13]

In the semi-rural 4th Battalion area, south of the city, Henry Murray recalled

In the Fourth Battalion area the principal criminal activities were in the nature of armed robbery and the stealing of cattle. Persons arrested by the Volunteer police for such serious offences were lodged in premises in the Tallaght area and kept under armed guard pending trial. The trials were carried out by Battalion officers and, as imprisonment was out of the question, punishment for very serious offences usually consisted of flogging or deportation. I acted as prosecutor in several cases which were disposed of by flogging or deportation which were found to be the only effective means of keeping serious crime in check.[14]

Armed robbery and murder exploded in Dublin alongside the collapse of the British state institutions.

Patrick Kelly of First Battalion in the north inner city similarly recalled his men being used to preserve order during the Truce, on one occasion using force to break up a riot between local youths in Smithfield and the local British Army garrison. But like other IRA officers, he was also involved in suppressing ‘ordinary crime’, on one occasion apprehending a gang led by a Royal Air Force deserter, which had stolen a sum of £2000 from a Dublin builder, that was meant to pay his workers. The gang was tracked down, held up at gun point and eventually given to the Republican Courts, who duly handed them over to the British military as deserters.[15]

This was lot of power for young men with guns, and no real legal constraints to have over the civilian population.

There were, before the Truce, only two working Dail Courts in Dublin – in Pembroke and Rathmines Wards according to Maire Comerford, (though Christopher Byrne of the 4rth Battalion remembered one working in Cuffe Street in the south city centre too[16]). By early 1922 after the signing of Treaty, it was clear that the newly empowered Irish authorities needed new, more permanent institutions for keeping order, in Dublin and elsewhere.

The British paramilitary police, the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries had never really been used in a law enforcement as opposed to counter-insurgency role, but they were in any case withdrawn and disbanded in early 1922. The RIC was formally disbanded in August of that year. The DMP remained but its morale at this point was at an all time low.

On 24th of January at an IRA GHQ meeting, Richard Mulcahy along with Rory O’Connor, Director of Engineering and Oscar Traynor, OC Dublin, discussed the ‘maintenance of order in Dublin’. Mulcahy cited a glut of recent robberies and ‘general disorder’.

Traynor agreed, implicitly acknowledging that some IRA members may have been involved in armed robberies and suggested all arms be put in Quartermasters’ hands that the IRA to take over policing in the city and to get ‘some place of detention’. It was proposed to set up a detective unit, a Criminal Investigation Department or CID with strength of 100 men. [17]

The CID

A file on CID strength on May 16th, 1922 shows 50 detective officers, a clerk and three drivers. Its acting OC by this time was Frank Saurin, one of Collins’ former IRA Intelligence officers. [18] The CID does not seem to have recruited ex Irish Republican Police, perhaps because many of them, like their chief Simon Donnelly, had anti-Treaty sympathies.

There were, however, many IRA Volunteers recruited from the start, some without any Intelligence background. Two such men, for instance, were Martin Hore and John O’Reilly, both veterans of the 1916 Rising and of the war against the British in Dublin, who both joined the CID in March 1922.[19]

While the CID was generally assumed to have been made up exclusively of IRA veterans, at least of its 27 men were former DMP policemen, including David Nelligan, who eventually headed the unit in late 1923.[20]

The Criminal Investigation Department or CID was set up in January 1922 to fight armed crime in Dublin after the Treaty.

The unarmed DMP, according to David Nelligan, were unable to cope with the wave of armed crime that accompanied the armed conflict in the city, the Irish Republican Police were ‘inefficient’ and the well-armed CID officers detailed to combat armed robbery had ‘plenty to do’ in early 1922.[21]

The CID and also related organisations such as the Citizens Defence Force and Protective Corps were effectively used as a pro-Treaty militia during the Civil War. All, but particularly the CID were accused of the abuse and sometimes killing of anti-Treaty prisoners – and most likely had some involvement in the assassination of up to 25 anti-Treatyites in the city. However, for the purposes of this article, the important point is that they were also a particularly blunt means of keeping order in Dublin.

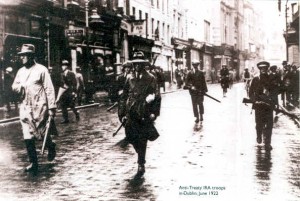

The Civil War and law and order

In March 1922 the IRA formally split over the Anglo Irish Treaty. In April, anti-Treaty elements occupied the Four Courts in central Dublin and sporadic clashes broke out between them and the pro-Treaty National Army throughout the city. On June 28 1922, all out Civil War broke out with the pro-Treaty assault on the Four Courts.

The collapse and fragmentation of the forces of order led, as well as rival militias shooting at each other and commandeering property, to an unprecedented level of violent crime in the city. In all of 1922, not counting killings as a result of political violence, the DMP filed 479 cases of armed robbery, 23 murders and 53 attempted murders.[22] This was a staggering rate of violent crime in a city in which murder had been a rarity before the First World War.

The forces of order, such as they were, were also much more violent than usual. Before 1920 and again after 1923 policemen in Dublin almost always went unarmed. Not so in 1922.

On June 22nd 1922, for example, three CID Detectives were called to a brawl in a tenement on Upper Rutland Street in the north inner city. John Lawless, a ‘usually quiet’ ex-soldier had drunkenly assaulted Mrs. Ball, wife of another veteran who lived in the same building.

During the arrest, according to the CID, Lawless tried to seize the revolver of a Detective McManus and was shot in the stomach and mortally wounded. At the inquest Mr Noyk the State solicitor representing the Detectives informed the Court that they always went armed, ‘In these times a policeman went about with his life in his hands’. The jury returned a verdict of ‘accidental death’. [23]

Had this incident occurred two years before or after, DMP policemen would have wrestled John Lawless to the ground or a worst hit him with their batons. Now the only body really attempting to enforce the law in Dublin was a heavily armed, poorly trained militia of the CID.

The Civic Guard

Most of County Dublin outside the city had always been policed by the RIC and with that corps disbanded, most of its posts were taken over first by the National Army and then by the new Free State police force the Civic Guard – later renamed to its Irish equivalent Garda Siochana.

Although it is part of the narrative of that force that it was, from the start, unarmed, in fact, in Dublin it was armed at the beginning of its existence.

Some of its first jobs in Dublin included guarding posts such as Dublin Castle and two Guards actually died in firearms accidents there.[24] An anti-Treaty raid on the police station in Dalkey in October 1922 netted a fair haul of arms.[25]

The Civic Guard, the replacement for the disbanded RIC, were often the targets of anti-Treaty attacks in Dublin.

At some point in late 1922, a decision was taken to completely disarm the Guards, but in Dublin and elsewhere this made them sitting ducks for the anti-Treaty guerrillas throughout he Civil War. In County Dublin, the police stations at Rathfarnham, Dundrum and Skerries were all blown up and destroyed in early 1923. Although the IRA first removed the unarmed Civic Guards from the buildings and there were no casualties, it showed the powerlessness of the new police force during the Civil War. [26]

Out of of over 200 people killed in the Civil War in Dublin, ten were policemen of different kinds, 5 CID, two CDF, two Civic Guards and one RIC member. This compares to at least 40 police killed in the city in the War of Independence, indicating that in 1922-23, it was the military who took the main burden of counter-insurgency rather than paramilitary police.

Re-ordering Dublin

The Irish Civil War of 1922-23 can be understood to some extent as the restoration of state power after a period of anarchy or ‘dual power’ in which the state was not able to monopolise either the use of force or the imposition of law.

As well as creating its own police and army to crush the anti-Treaty ‘Irregulars’, the pro-Treaty Government also began to overturn some of the institutions created by the nationalist revolution since 1919.

The Sinn Fein or Dail Courts were wound up, after some Republican prisoners appealed to them for release on the grounds of Habeus Corpus (that they had been imprisoned without charge). On October 4th it was decreed that the Republican Courts were abolished and that ‘all business is to be wound up’.[27]

The Free State abolished the Republican Courts system and resurrected the old British legal system by September 1922

The previously existing British Courts system had actually been resurrected in early 1922 but was fully back up and running as the Free State legal system by September 13th. With Four Courts destroyed, it was decided to accommodate them temporarily in Dublin Castle, the former seat of British rule, where they were to be advised by Lord Glenavy, a formerly a leading Dublin Unionist, now a firm Government supporter[28].

As for the DMP, their strength as of April 1, 1922 was 1,126. Unlike the RIC they were retained by the Irish Free State under the Treaty but nearly half – 574, took the option to retire rather than to serve the new state. The Commissioner Edgeworth Johnson retired in April 1923, to be replaced by WRE Murphy.[29]

Murphy had served in the British Army in the First World War, rising to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, before returning to his job as schools inspector in County Derry. In early 1922 Michael Collins recruited him to the Free State’s National Army, where he held the Kerry command until December 1922. In many ways he therefore represented the integration of elements of the old British officialdom into the new Free State.

The CID, the rough and ready corps of ex IRA gunmen was disbanded in October 1923. At the height of the Civil War, its strength had stood at 73, but only eleven of its detectives were deemed fit to join the new reconstituted new 62 man DMP G Division – which soon evolved into the Garda Special Branch.[30]

WRE Murphy a National Army officer was given command of the DMP and oversaw its integration into the Garda Siochana, the new national police force.

The DMP had continued to operate during the Civil War, but during the armed conflict it could do little to dent the crime figures. Pursuit of the anti-Treaty ‘Irregulars’ was left to the CID and the National Army.

It was only after the Civil War that the figures for apolitical as well as political violent crime began to fall. In 1922 there were 23 ‘ordinary’ murders, in 1923, 16 and in 1924 it was back down to peacetime levels of just two homicides. There were still however 142 cases of armed robbery in Dublin in 1924, albeit down from 210 cases in 1923 and 479 in 1922. [31]

It took some time for this wave of armed crime to blow itself out as demobilised National Army soldiers and recalcitrant IRA guerrillas both carried out armed robberies in the wake of the Civil War. A former National Army soldier was hanged for instance in Dublin in November 1923 for shooting dead a CID officer during a bank robbery.[32]

WRE Murphy’s signal achievement as the last Commissioner of the DMP was closing down Dublin’s red light district ‘The Monto’ in 1924. In 1925 the DMP was incorporated into the national police force the Garda Siochana as the Dublin Metropolitan Division. Murphy went on to serve as the assistant commissioner of the Gardai under Eoin O’Duffy, another former pro-Treaty soldier turned policeman. [33]

By that date the revolution, the competition between rival aspiring state groups, was over in Dublin. The crime wave that had accompanied the dismantling of the British system of policing was also over. The city faced a future under a new, Irish police force.

References

[2] Jim Herlihy, The Dublin Metropolitan Police, a Short History and Genealogical Guide, Four Courts Press, 2001, P8-25 The RIC had been effectively in existence since 1822 but was formally codified in the same year

[3] Ibid. pp 25, 122

[4] Joseph V O’Brien, Dear Dirty Dublin, A city in Distress, 1899-1916, p180-185

[5] Padraig Yeates, Dublin, A City in Turmoil 1919-21, p47

[6] John Borgonovo, Republican Courts, Ordinary Crime and Irish Revolution 1919-21,In, Justice in Wartime and Revolutions, , Ed.s Margo De Koster, Herve Leuwers, Dirk Luyten, Xavier Rousseax

[7] George Dwyer BMH

[8] Yeates Dublin A City in Turmoil, 1919-21, p189

[9] Maire Comerford papers, UCD LA/18/17

[10] Herlihy, Short History of the DMP p182

[11] Yeates, A City in Turmoil, p161

[12] UCD Maire Comerford Papers LA/18

[13] Joseph O’Connor BMH

[14] Henry Murray BMH

[15] Patrick Kelly BMH WS

[16] Christopher Byrne BMH

[17] Mulcahy Papers UCD P7/A/67

[18] UCD MP P/7/B/26 file on CID, May 16 1922

[19] Military Pensions, applications of John O’Reilly and Martin Hore.

[20] Their names are listed in Herlihy, Jim, The Dublin Metropolitan Police –A short History and Genealogical Guide, 1836-1925, p152-153

[21] UCP MP P/7/C/29 Testimony of David Nelligan to Army Inquiry 1924.

[22] Herlihy, Jim, The Dublin Metropolitan Police –A short History and Genealogical Guide, 1836-1925, p186

[23] Irish Times June 26 1922

[24] A Civic Guard is accidentally shot fatally wounded by his comrade in Ship St Barracks (horseplay), dies on 24th, Charles Eastwood, (19). (Irish Times September 30 1922)5 October A Civic Guard commits suicide, shoots self, in Ship St Barracks, James Green (Irish Times October 7, 1922)

[25] 27 October, Dalkey DMP Station taken over by the IRA. Three automatic pistols and 2 ‘rook’ rifles taken. (CW/OPS/01/02/07 GHQ Misc. reports) IRA reports 1 Lee enfield, 2 martini and 2 Rook rifles taken ‘all safely dumped’. (Dublin 1 Bde reports to AACS p69/77)

[26] 12 January 1923 Rathfarnham Civic Guard Barracks is blown up by the IRA. 6 men armed with revolvers removed the 2 Guards and the civilians from the neighbouring houses, then detonated a powerful mine. (Irish Times 13 January 1923)27 January 1923 Dundrum Civic Guard Station burnt down. 13 February Skerries Civic Guard Station blown up. (CW/OPS/07/02)

[27] Cabinet Minutes 4/10/22 P7/B/245

[28] Cabinet Minutes 13 September 1922 Mulcahy Papers P7/B/B/245

[29] Herlihy, Short History of DMP p183

[30] Department of Home Affairs report into disbandment of CID NAI TAOIS/S/3331

[31] Herlihy p 186

[33] http://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/an-irish-general-william-richard-english-murphy-1890-1975/